|

An Accidental Career – Looking back at my life as a sexologist

3. A Textbook of Human Sexuality

5. World Congress of Sexology in Jerusalem

7. Practical Sexual

Medicine

9. AIDS

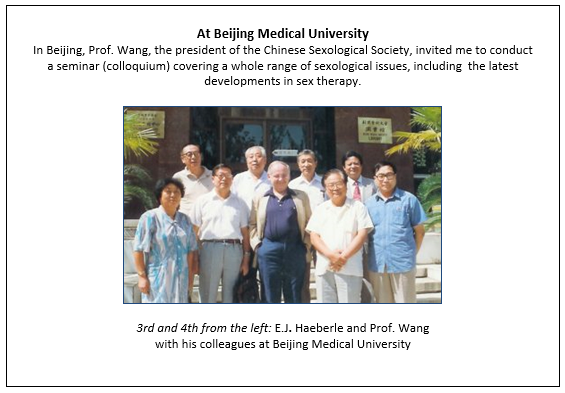

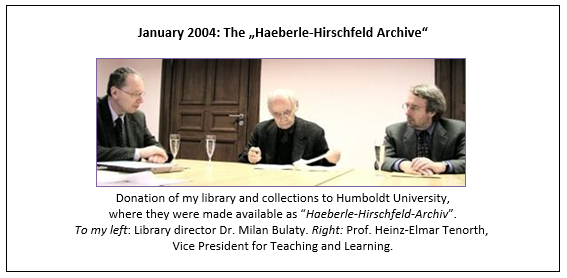

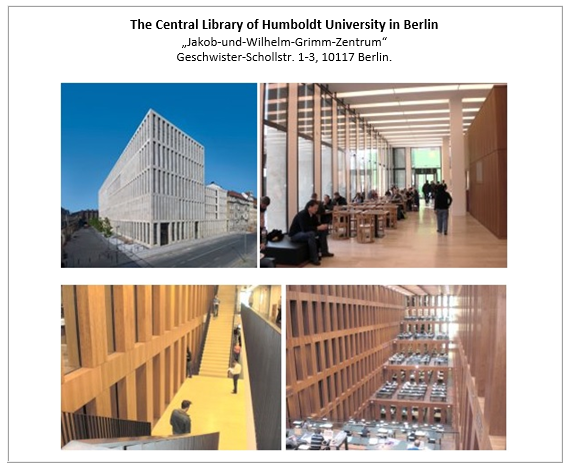

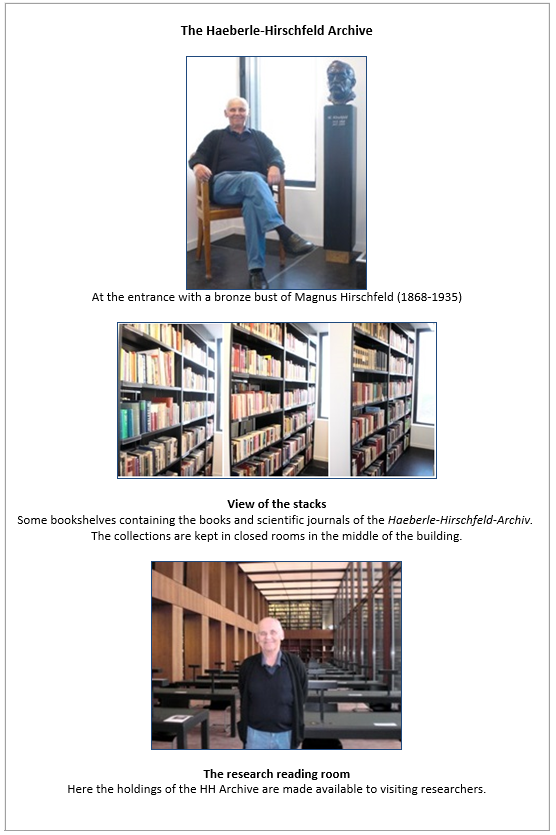

12. Visiting Professor at Humboldt University

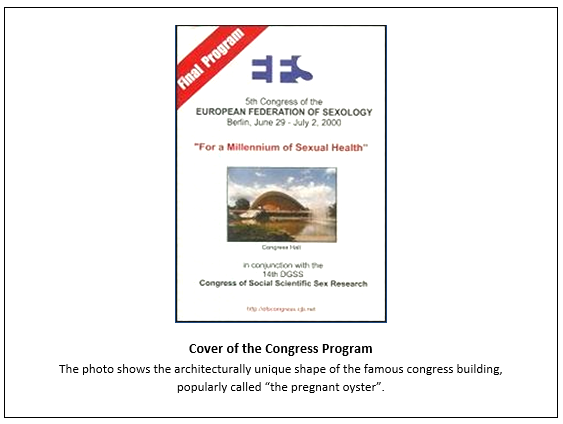

14. The largest sexology congress in Berlin

16. Travel to other countries

Erwin J. Haeberle

An Accidental Career

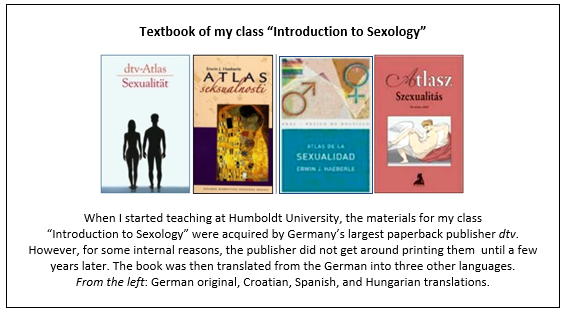

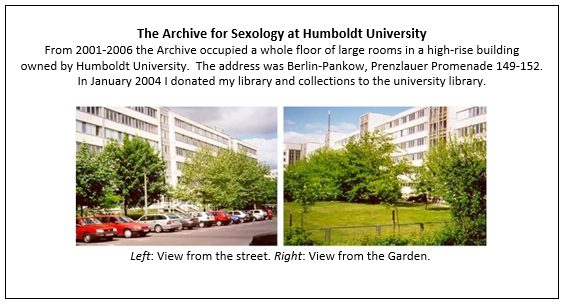

Looking back at my life as a sexologist

This selection offers texts written over the last 40 years. I

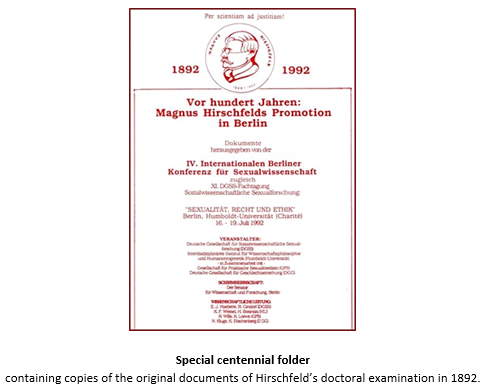

wrote them spontaneously or on invitation, depending on various

circumstances at the time. In any case, they did not follow an

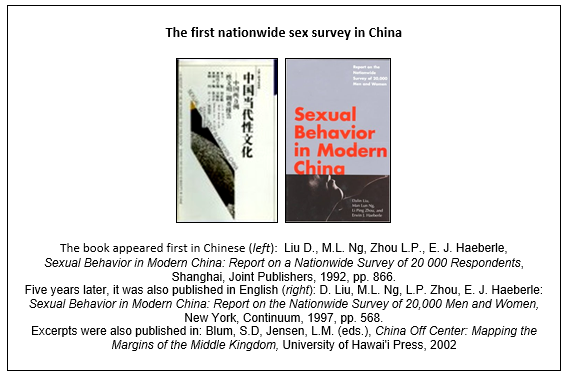

overall plan or design. Also, I do not present them here in

chronological order.

As I realize now, apart from my textbook “The

Sex Atlas”,

most of my print

publications in English over the last 40 years have been dealing

with historical matters, either with the history of sexology

itself or with related subjects. They make up the bulk of the

present volume. Only the last six of the texts address current

problems and try to look into the future not only of my own

field of study, but of the academic world in general.

The collection ends with an updated

Chronology of Sex

Research that I had written long ago when I first became

interested in sexology.

Fortunately, in this online version of my book, I can present my

most important contribution to our field, i.e.

the invention and pioneering of “open access” online

courses (today known as MOOCs). In January 2003 I put the first

of these courses online under the title “Basic

Human Sexual Anatomy and Physiology”.

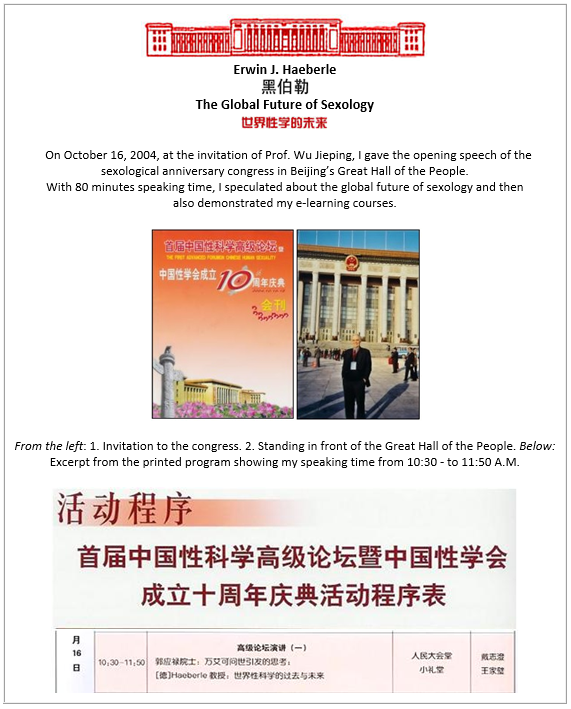

One year later, in 2004, I demonstrated it with some additional

courses at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People, and soon

thereafter they were translated not only into Chinese, but also

into other languages. Today, I am offering a complete curriculum

of 6 courses (6 semesters) in sexual health in the internet,

freely accessible in

English, Spanish, Portuguese,

Chinese (in simplified and traditional script),

Russian, Czech and Hungarian.

Some of the courses are also available in other languages. If

used by professional organizations, this curriculum can lead to

certificates or diplomas and, if used by universities, it can

lead to academic degrees (B.A. or M.A.). Moreover, it can be

studied not only on PCs, but also on tablets and smart phones.

At this time, however, I am aware of their regular use only in

China, where they help in the training of a great many sex

educators every year. American and European universities and

professional organizations still seem reluctant to take

advantage of my offer and to follow the Chinese lead.

Returning to the present text selection, I would like to add a

few comments on my own family background, academic training, and

career:

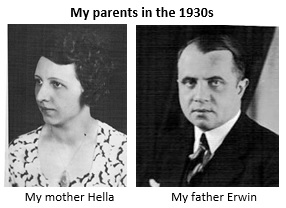

My parents were both born in the same year 1902 in our hometown

Bochum. Neither of them enjoyed any form of higher education.

Throughout her long life, my mother was a “Hausfrau”. A

few years after the sudden death of my father at the age of 60,

she moved to Brussels, joining my sister, who had married a

lawyer at the EU. When he also unexpectedly died at a young age,

my mother was able to support her daughter in the household and

to help her in bringing up her two small sons. She was fortunate

enough to see her beloved grandsons grow into successful

university graduates. As she often said: These were the happiest

years of her life. She died at the age of 94.

My father had received some training at a local bank, but, as a

still very young man, had become self-employed as a book keeper

for a number of small and medium-sized, mostly Jewish

businesses. However, with the anti-Jewish race laws of 1935, the

authorities presented him with a “Berufsverbot”,

i.e. a prohibition to continue working in this capacity.

After the war, he did not speak very much about what must have

been a traumatic experience. I do remember though, that he once

mentioned taking the train to Amsterdam and smuggling a great

deal of cash - sewn into his jacket -

to one of his former Jewish customers, whose family was

ready to board a ship to Argentina. The money was theirs of

course, but they had not been able to take it with them when

they fled.

At that time, he started a new career as a self-employed sales

representative of several shoe companies, receiving a percentage

of his sales.

However, after a promising start, even this ended suddenly with

the beginning of WW II. On its first day, my father was drafted

into the army, and 6 years later, still a private, he deserted

in the spring of 1945 from the Western front, which, by that

time, had moved rather close to our city. He put on civilian

clothes, evaded arrest and imprisonment by the allied troops and

came home.

Looking back now at the first, very hard post-war years, I

remember three things about my father:

1. He apparently still clung to the world he knew best and loved

before the Nazis had come to power. This showed itself in his

language, which had remained full of Yiddish expressions (I am

using here the German spelling): The words “Tacheles”,

“koscher”, “meschugge”,

“die Mischpoche”, “der

Zores”, and “der

Dalles” were parts of his everyday speech. Sometimes he used

the words along with some sarkastic comments like: “Gannef,

the son-in-law”, or “Tinnef,

the wedding present” etc.. This unshakable habit was

obviously an echo of his early working life. I don’t know how he

got away with it during the entire “Third Reich”.

2. In 1946 he found that, as the only one of her family, a

daughter of one of his former Jewish customers had survived the

Buchenwald concentration camp and had returned to Bochum. When

we visited her, we found that she had married another camp

survivor, and that his 17-year-old nephew, still another

survivor of the same camp, was living with them. My father

explained the situation to my sister and me, 8 and 10 years old

at the time, and we fully understood, but we were more

interested in something else: The new Jewish family invited us

to a good meal and repeated such invitations in the following

months and years. These were the “hunger years” in Germany, and

we children therefore always looked forward to another visit.

For us, each of these meals was a feast, as it must have been

for them after the horrible years of their suffering and

deprivation. (As Holocaust survivors they had different rationing cards.) Soon, the young nephew succeeded in immigrating to

New York. From there, he sent us children a CARE package

including, among many nourishing goodies, a Woody Woodpecker

comic. Without understanding it, I read it over and over and

decided right then that someday, somehow, I would also go to

America. I especially remember one spring afternoon. It must

have been May 14, 1948, because we were celebrating the founding

of Israel with coffee and cake. The cake had all all-white sugar

coating decorated with blue butter cream forming a star of

David, and there were also little paper flags with the same

design. This was the first time I saw Israel’s national flag,

and without understanding the full implications of the event, I

was fascinated. (Later, I found out that May 14 was also the

date of Magnus Hirschfeld’s birth and death.) 3. These long forgotten memories are now coming back to me as I write. However, there is one episode from that time that I have always kept in mind. It was a lesson for life my father taught me in a single sentence: One day, I must have been 10 or 11 years old, he showed me a sizeable, illustrated Nazi propaganda book from the 1930s which he had found in the rubble of one of our city’s bombed-out houses. The volume had a large fold-out of several pages. It showed thousands of people at a Nazi rally in front of a wall of swastika flags. My father pointed to this photo and said: “Take a good look at these people and remember that they were all against it!” I immediately understood. He was talking about the stupidity, gullibility, and hypocrisy of the masses. He was also talking about our policemen, train conductors, and store owners, indeed about our teachers and our neighbors. Even as a child, I myself remembered how many of them had been fanatical supporters of Hitler and now claimed to have been secret opponents. The more I thought about it, the more I realized the dangers of blind obedience to authority and of unquestioned general assumptions. I also saw that adults lie, and lie with conviction, not only to others, but also to themselves. Thus, even before I entered my teens, I became skeptical and critical of “the will of the people” and of every social and political “established order”.

I

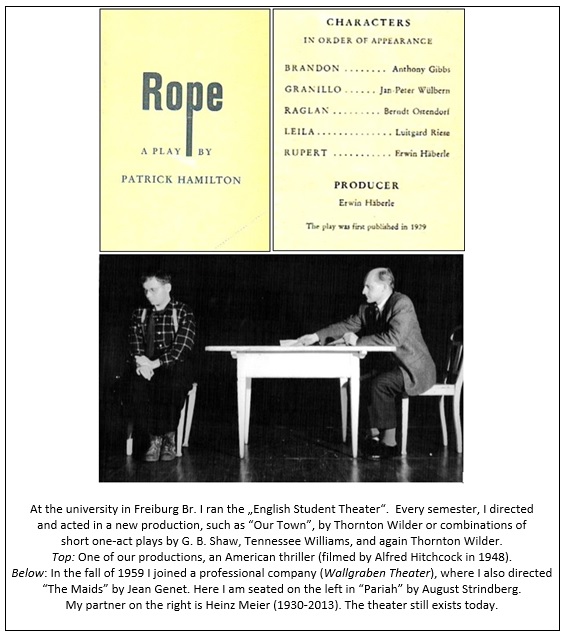

became a sexologist in my middle thirties more or less by

accident. Originally, I had begun studying theater history,

German and English literature at the universities of

Cologne and

Freiburg Br. I

financed my studies first by working in various factory jobs

during academic vacations, later as a janitor in some large

wooden library shack for students, and eventually as an actor

and director in a private professional theater.

After this difficult beginning, I eventually

succeeded in winning some scholarships, and this enabled me to

continue studying at the universities of

Glasgow,

Heidelberg,

and at Cornell.

1. From Heidelberg to the USA

2. Cornell

(1963-1964)

Cornell’s foreign students came from all over the world. In my

student dorm (Cascadilla Hall), I lived door to door with

students from the Soviet Union.

They were upset when we saw Kubrick’s latest movie „Dr.

Strangelove“, as they were quite unprepared for this kind of

biting political satire. But they were utterly shocked and

frightened when, in early November, President Kennedy was

murdered in Dallas. For days, we all followed the live TV news

reports in our common room.

As to cultural events, I remember, above all, a concert on

campus given by the then still relatively unknown Bob Dylan. But

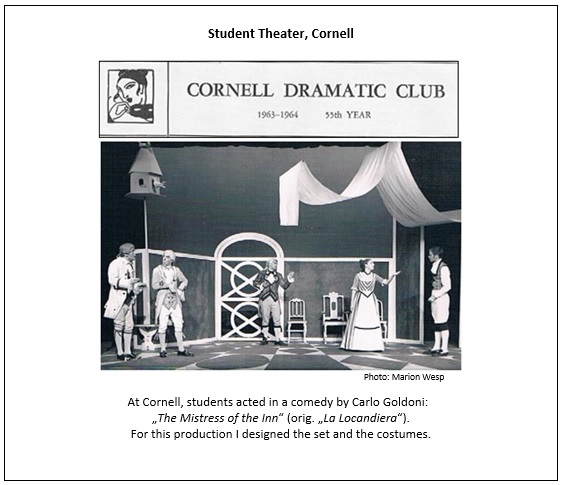

Cornell students also showed their own productions in the

University Theater. For one of them, Goldoni‘s „The Mistress of

the Inn” (La Locandiera),

I designed the sets and costumes.

In addition, the student film club regularly showed old

Hollywood movies, and these introduced me to the great comic

actors of the 1930’s and 1940’s of whom I had never heard before

- the Marx Brothers, Eddie Cantor, and especially the

incomparable W. C. Fields. The

current TV shows (still in black and white) featured the

lovable, amusing series with Jack Benny (The Jack Benny

Program). Later, I saw

reruns of the hilariously funny shows with Sid Caesar (Your

Show of Shows), Jackie Gleason (The Honeymooners) and

Lucille Ball (I love Lucy).

I was also lucky enough to see the great Jewish stand-up

comedians of the older generation: Milton Berle, Henny

Youngman, Shelley Berman and Alan King – all of them masters of

their trade. This introduction

to American humor and it various traditions helped me greatly in

understanding American culture.

Throughout, I remained a faithful fan of the American grotesque

comedy shows - later in color -

from Danny Kaye to

the unforgettable

Carol Burnett and the distinguished

looking, but always hilarious Harvey Korman. I also enjoyed the

TV appearances of Jerry Lewis. Of course, not all television

humor was rooted in Jewish traditions. There were also wonderful

black comedians from Redd Foxx to Flip Wilson, Eddie Murphy and

Richard Pryor. Very often I watched Johnny Carson, a real “pro”,

who dominated “late night television” during the entire time of

my stay in the US. I greatly admired Dean Martin, the most

relaxed of all performers, with his occasional guest Foster

Brooks. Most impressive

were

later the strange, daring, and baffling presentations of Andy Kaufman and the breathtaking solo peformances of the “avant-garde” comedians Jonathan Winters and

Robin Williams. American television changed a great deal over

the years, reflecting the larger social changes in the country.

For me, its humor remained an important key to understanding the

complex “New World” I lived in for so many years. I left Cornell

in the summer of 1964 with an M.A. degree.

When I returned to my English department in Heidelberg with my

degree from Cornell, I was given a position as “wissenschaftlicher

Assistent” (roughly equivalent to an assistant professor)

and started to write my dissertation about the plays of the then

still living novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder.

(1)

Two years later, I received a Ph.D. (Dr.

phil.) in American literature.

3. Yale

(1966-1968)

Pearson was also financially quite comfortable.

One day, when he and his wife had invited me to tea, he

surprised and amazed me by taking a „Shakespeare

Folio“ from

his book cabinet. (He also owned several Quartos.)

Other examples: The license plate of his large luxury car did

not show any numbers, but instead his full name. When, right at

the beginning, my stipend turned out to be too low, he saw to it

that it was immediately raised and gave me a personal check for

the time already passed: “This is not a loan!”. His unexpected

early death shocked me. I still think about him often with deep

gratitude.

At that time, Yale was an all-male school, i.e. without female

students and hardly any female professors (I met only one).

Indeed, the Ivy League football games in our stadium offered

male cheerleaders - an unusual, very interesting sight - now

gone forever. The “downside” was an “uptight”, stuffy,

pretentious and boring, emphatically masculine atmosphere on

campus. On the other hand, the university offered many memorable

cultural events, for example symphony concerts, opera arias with

Renata Tebaldi, Shakespeare’s sonnets recited by John Gielgud,

meetings with authors like

Robert Lowell, Joseph Heller, Robert Penn Warren, Norman Mailer,

and Tom Wolfe, who

had received his Ph.D. in American Studies under Norman H.

Pearson and always wore a white three-piece suit.

There was another evening with the boxer Muhammad Ali,

whom I could see (and almost touch) up very close – a

hero radiating strength and good health. I also saw the actor

Paul Newman up close: He looked even better in private than in

his films.

Of course, I also used every opportunity to see not only the

latest Hollywood movies, but also many old ones. I especially

remember one of them: "Wonder Bar" (1934) with Al Jolson singing

in blackface. For me as a European “postdoc” in American Studies

it was a revelation that prompted me to do some additional

research. Thus, I learned a great deal about the old minstrel

shows, and indeed about the original stage figure of “Jim Crow”

as part of American cultural history.

The university theater under its director Robert

Brustein featured stars like Irene Worth, Stacy Keach, and

Kenneth Haig. Some young

students also tried acting, and later some of them had

respectable careers in Hollywood. For example: I saw the

stunningly handsome undergraduate Perry King playing a leading

role in the student production of Thomas Dekker’s “The

Shoemaker’s Holiday”. It was practically foreordained that

he should go to California and lend his good looks to the

movies. Henry Winkler, a drama student, became a television star

as “the Fonz” in the popular series “Happy

Days”.

He was also successful as a producer. The most popular professor

on campus was a specialist for the ancient Greek classics -

Eric Segal, author of the bestselling novel „Love

Story“,

which also became a successful film. Another bestselling author

was the Yale law professor Charles A. Reich with „The

Greening of America“.

He suddenly resigned from his position and moved to California

close to San Francisco as a „free spirit“ and gay activist.

Since a train ride from New Haven to New York takes only about

two hours, I often used the opportunity to enjoy the cultural

events in Manhattan. I usually stayed a couple of nights at the

YMCA and visited museums, theaters, and the two recently opened

opera houses at Lincoln Center. At the MET, I saw a visually and

musically overwhelming production of „Die

Frau ohne Schatten“ by Richard Strauss, conducted by Karl

Böhm, and Wagner’s “Die

Walküre”, conducted by Herbert von Karajan and with Régine

Crespin as Brünnhilde. Most importantly, I saw and heard Wieland

Wagner’s unforgettable production of his grandfather’s “Lohengrin”

with the vocally ideal Sandor Konya in the title role. (I had

seen an earlier version of the same production in Berlin with

the tenor Jess Thomas). At the NYCO, Beverly Sills became an

overnight sensation in Handel‘s „Giulio

Cesare in Egitto“.

All of these performances are still available on CDs, and I

still enjoy listening to them today. In those years, I also saw

all important plays and musicals, for example the first

performance of “Hello Dolly” with Carol Channing, after a play

by Thonton Wilder (after Nestroy). While at Cornell, I had

already seen the original production of Albee’s

“Who’s afraid of Virginia Woolf?” in New York with Uta

Hagen and Arthur Hill – a triumph of acting, much more intense,

gripping, and shattering than Taylor and Burton in the later

film. During my 4 years on the East Coast, I also had the chance

to attend all important ballet performances

- from the

NY City Ballet and Alvin Ailey’s American Dance Theater to Merce

Cunningham and his company. (Many years later in Germany I met

his partner John Cage at the house of a mutual friend.)

Sometime during my stay at Yale I gave a lecture on some

literary topic at

Brown University

in Providence, RI, another member of the Ivy League. I have

forgotten the subject and the date, but I remember clearly the

special atmosphere

enlivening the campus. It

was a bright, warm summer day of an art festival, because I had

the thrill of seeing and hearing an open-air concert by the

legendary Dizzy Gillespie and his band. At the edge of a large

lawn Allen Ginsberg sat under a tree with a group of his

admirers. I simply joined them and was welcome.

In the course of my American studies, which went quite well, I

became interested in American-Japanese cultural relations and

succeeded in obtaining another scholarship and moved on to the

UC Berkeley.

At this point, I’d like to mention a special experience, which I

had the privilege of enjoying twice:

For us foreign students, Cornell had

organized personal meetings with important personalities

in Washington DC (members of the administration, senators,

members of the House of Representatives etc.), and Yale

did the same. Thus, I was fortunate enough to be present a

second time when the most liberal justice William O.

Douglas (1898-1980), received us at the US

Supreme Court. He

talked to us for about one hour, improvising in a relaxed,

humorous manner, answering all our questions directly, clearly,

and without hesitation. He was, in every way, an “authentic”

human being, independent, unafraid, highly intelligent, and, in

his language, “close to the common people”. During my lifetime,

very few men have impressed me as much as he did. He was, in

thought and in speech, a truly free man - the very best American

culture can produce. I never saw anyone like him in

Europe.

4. UC Berkeley

(1968-1969)

Bellah was one of the most important cultural historians of his

time, and, in this sense, he was himself an „establishment

figure“, but his attitude toward the political and academic

establishment remained cool and reserved. In any case, in

California he had found a position commensurate with his

enormous talents and merits.

In our personal meetings, he was always serene and generous,

once again a “man of real class“, just as Norman H. Pearson.

In Berkeley, I signed up for a basic Japanese language course

and made Japanese friends. I

also took advantage of the famous Asian Art Museum in San

Francisco. Moreover, the city has a fascinating Japanese

district (Nihonmachi) with Japanese restaurants, shops, a

large Japanese bookstore, and a theater. There, I was lucky

enough to catch two extraordinary performances of the „Grand

Kabuki“ from Tokyo. (I had already seen

Bunraku and Noh

elsewhere.) Because

of the enormous costs of bringing the company and its marvelous

sets and costumes across the Pacific, the visit was never

repeated.

But back to the strictly academic:

If everything had worked out according to plan, I would

have written about authors like Lafcadio Hearn and John Luther

Long, who were the first to introduce Japanese topics to

American readers.

(The latter wrote a Japanese story, which was made

into a play by Belasco, which was turned into an opera by

Puccini. See below.) In this

context, it would also have been appropriate to investigate the

influence of European „Japonism“and generally of

„exoticism“ on American culture. Bellah was a competent guide in

all of these areas.

Soon enough I had collected the necessary amount of material

that would enable me to pursue my interests in several promising

directions. For example: In the later 19th century, European and

American theaters both created and catered to a certain

“Japan fashion” by turning to Japanese topics or using

“exotic” Japanese settings . (As early as 1885 the satirical

operetta „The Mikado“

by Gilbert and Sullivan had its première in London, and in

1896 , in the same city, the musical comedy „The

Geisha“ by Sidney Jones was a great success, almost

immediately repeated in New York. Two years later, in

1898, Mascagni presented his „Iris”,

a first „Japanese” opera in Italy.)

I was especially interested in the American David

Belasco, author of two plays that inspired Puccini to turn them

into operas: „Madame

Butterfly“ (1904) and „The

Girl of the Golden West“ (1910).

Belasco was an important figure in the history of the

theater. Exploring his cultural background in San Francisco and

later in New York would have been an interesting challenge.

It could have yielded fresh insights into the interplay

of technology, art, and commerce in the US before the First

World War. However, things turned out very differently.

5. Return to Heidelberg

However, to my total shock and surprise, my jealous colleagues

had taken advantage of my absence and some administrative rule

changes for a clever intrigue: They had succeeded in making my

job disappear and thereby eliminating me as a competitor. As a

result, at the age of 33, I suddenly found myself unemployed,

uninsured, and penniless. After all, living on scholarships, one

cannot build up a savings account. For me, this sudden end of my

well-planned and smoothly running career was a truly traumatic

experience. After all, British, American, and German sponsors

had, over the years, invested tens of thousands of pounds,

dollars, and DMs in my academic future, and now it was all for

naught. The German university system proved too inflexible to

offer me a ready alternative. Having no money at all, I needed

immediate employment, but, at that time, there simply were no

suitable positions available at any university in Germany. I

felt abandoned and betrayed by a system I had blindly trusted.

Living in my hometown Bochum with my widowed mother, who

received only a very small pension, I was devastated and did not

know what to do next. (As I write this, it suddenly dawns on me

for the first time that, because of the Nazis, my father had

also suddenly lost his job and his income at the same age of

33.)

6. Return to Yale

(1969-1970)

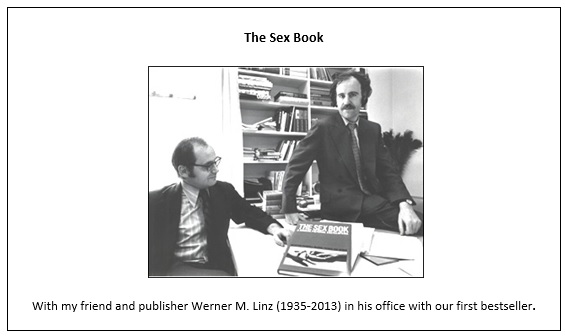

Fortunately, I had a boyhood friend from Bochum,

Werner Mark

Linz, who had immigrated to the US, married, and started to run

a new publishing company in New York.

He gave me an advance for some minor, purely commercial

projects that I could easily manage from my home in New Haven.

They became so successful, that I could soon pay back the

advance and forget my financial problems. I also began to visit

him and his family in Rye NY for long weekends or even several

weeks at a time. Often together with his wife, we visited

museums and shows in Manhattan. It was a practice we continued

over many years, even after my move to California. In the meantime, Yale had, for the first time in its history, admitted female students ("coeds"). Their arrival in the fall of 1969 produced a revolutionary and very beneficial change in the atmosphere on campus. The former ostentatious masculinity with its typical pretensions, inhibitions and general stuffiness, was, almost overnight, replaced by a relaxed, easy-going friendliness. Indeed, paradoxically, the transformation of campus life was so radical that some formerly “closeted” students spontaneously founded a Gay Alliance at Yale (GAY), which organized social gatherings on campus.

The new group also organized well-attended all-male dances. Of course, just a few months before, Manhattan

had seen the now famous “Stonewall riots”, a successful

customers’ revolt against police harassment of a “gay” bar, and

this was probably also a factor in the new assertiveness. There

was one disadvantage, however: Yale’s fantastic, large all-male

“gym”, where we were used to the sights of complete nudity, now

had to be shared with the new female students. Earlier, we were

handed our towels when we entered the huge building, put our

clothes in a locker, and roamed around the hallways and

elevators in the nude. We wore clothing only as a particular

sport required it (I myself wore shorts for some group

gymnastics, and so did the others in teams sports etc.).

However, we always swam nude in the Olympic-size swimming pool.

Indeed, when entering the pool area, one had to walk with spread

legs over a special contraption that sprayed water on one’s

crotch, giving it an extra washing. (Obviously, this “crotch

sprayer” would have made no sense for men wearing swimming

trunks.) Nudity was also the rule in the large, common showers,

steam baths, their connected resting areas and massage rooms.

Now, all of a sudden, in most parts of the gym, we had to wear

boxer shorts or swimming trunks. (Cornell, coeducational from

the start, had two gyms, one for females, and the other for

males. Both could be used in complete nudity.) Still, after a

while, we “Yale males” had all accepted the change as a minor

inconvenience.

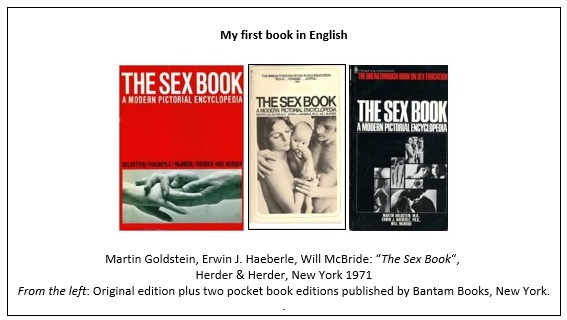

During this, my third year at Yale, I accidentally came across a

German news report about a new and very unusual German book – an

“encyclopedia of sex” for young people, containing brief

articles on subjects from “Abtreibung”

(abortion) to “Zygote”.

It was illustrated with wonderful, very explicit photographs.

The text had been written by the physician Martin Goldstein

(1927-2012) who, under the pseudonym Dr. Sommer, ran a popular

sexual advice column in a German youth magazine. The

esthetically appealing photographs had been taken by the

American photographer Will McBride (1931-2015) who also lived in

Germany. When I obtained a copy of this work and showed it to my

publisher friend Werner Linz, he was enthusiastic and quite

eager to produce an American edition.

However, upon closer inspection, it turned out that a direct

translation would make no sense in the US. The cultural

differences between the two sides of the Atlantic were simply

too great. Indeed, as we learned from this concrete example, the

concepts of human sexuality are, to a very great extent, shaped

by socio-cultural forces. In other words: The same “facts” are

of greatly varying importance and take on different meanings in

different cultural contexts. This is especially true when it

comes to the sexual lives of young people. For me, this was a

startling insight that triggered a general interest in the

subject matter and eventually led me to a career as a sexologist. In

short: Both my German-born friend and I realized that, for an

American edition, the book would have to be rewritten. Indeed,

even some of the photos had to be reshot, because they showed

the typically uncircumcised penises of German males, while, as

I had learned in the “gyms” of Cornell and Yale, most American

males are circumcised.

So, in order to make an American publication possible, we

obtained the permission of the original authors for a

substantial change. I myself rewrote the entire text and added

my name as a co-author to the new edition. I also gave it a new

title: “The Sex Book”.

(2)

Before I left Yale at the end of the school year, I handed in

the completed manuscript, and when the book finally appeared in

the following year, it caused a sensation. It was, in the same

week, reviewed very favorably in both “Time”

and “Newsweek” and

soon became a bestseller. I was invited to radio and TV shows,

“schlepping the book” up and down the North-East Coast (New

York, Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh), even to the Mid-West

(Cleveland, Chicago), and almost made it to Johnny Carson’s

“Tonight Show”. I was invited to his studio, then still in

Manhattan, where I found a number of other potential guests

waiting. After a preliminary interview with his sidekick

Ed McMahon I was ready to go on, but

in the last minute they apparently found someone even more

interesting. No matter, the book kept selling very well indeed.

Eventually, it went through several additional paper-bound

editions of different sizes. From that time on, I no longer had

any financial problems. Needless to say, the other two authors

in Germany also profited very handsomely and had no regrets at

all about having trusted my judgment and allowed me to go ahead

as I had seen fit. Many years later, I was able to visit Dr.

Goldstein in his home in Düsseldorf for a cozy afternoon talking

about our old publication and our latest experiences in Germany.

7. Return to UC Berkeley

(1970-1971)

With my second postdoctoral fellowship at UC Berkeley I returned

to the place of an earlier, life-changing experience: In 1967, I

had traveled from Yale across the US to California for its now

legendary “summer of love”. As a “seasonal hippie”, I had lived

with many others in a large “Hippie House” and participated in

all their activities, including the famous concerts in San

Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium. (I had also attended a live

concert of Janis Joplin in Palo Alto.) Without going into

details here, I can say that this summer had a profound and

lasting effect on my thinking and general outlook. The “flower

children” rejected the stifling conformity of the

preceding

decades and their stereotypical sex roles, performance pressure

and social inequality. Instead, they led unassuming,

undemanding, modest, relaxed, tolerant lives under the motto

“live and let live” or, as they themselves put it: “Do

your own thing!”

and “If it feels

good, do it!” Following Timothy Leary’s advice: “Turn

on, tune in, drop out”, they smoked “grass”, took LSD and

cultivated a non-aggressive privacy while, at the same time,

remaining open to a wider, like-minded community. Indeed, they

created this steadily growing community by their very existence.

Their passive, peaceful attitude was enough to attract ever more

followers. It was the awakening of a whole generation, not a

fad, but a movement. Observing it “live” on location, I

discovered an unsuspected side of the US. This “other America”

revealed an enormous untapped creative potential boiling just

below its surface and behind the “official” established image.

“Psychedelic” art and music, colorful,

loose-fitting clothes and long hair, large peaceful

gatherings (“be-ins”),

subversive new books and pamphlets, uninhibited cartoons,

“underground” papers like the “Berkeley

Barb” with an explicit advice column about drugs, sex, and

sexually transmitted diseases (“Dr.

HIPpocrates”) as well as personal ads for sexual contact –

all of this signaled coming social changes. Indeed, as it

eventually turned out, the “hippie revolution” had far-reaching

consequences for the entire country. Some knowledgeable writers

now even claim that it was the true source of our present

electronic revolution.

(3)

Of course, this was also a time of increasing mass protests,

especially against the war in Vietnam. The Berkeley “free speech

movement” of 1964-1965 had laid the groundwork for all sorts of

“civil disobedience” and protest rallies. The war increased and

intensified student demonstrations all over the country. During

my second stay in Berkeley (or “Berserkeley”, as it was called

in the press), I found myself in a highly charged general

atmosphere. The whiff of tear gas hung in the air as I went to

the library, where the then governor Ronald Reagan had posted

National Guardsmen with open bayonets at the entrance and that

of all other campus buildings.

Within a few years, the “hippie scene” had changed drastically.

In addition to “grass” and LSD, other, “harder” drugs had become

popular. The murderous “Manson family” had revealed a dangerous

underbelly of the formerly peaceful subculture. The growing

anti-war protests had led to the destructive violence of the

“Weather underground” and to

overreactions of the government, culminating in the

shooting of unarmed students by the National Guard at Kent

State University in 1970. (In 1969, a student protester had been

killed by the police in Berkeley.) It was a violent decade.

A much discussed dictum at the time was that of the black

American radical

activist H. Rap Brown:

“Violence

is as American as cherry pie”.

The killing of civil rights workers in Mississippi (1964) and

the assassinations of

Martin

Luther King and Robert Kennedy (1968) formed an unsettling

contrast to the peaceful aspirations of the young. Indeed, the

whole country felt increasing unrest on many sides. As a foreign

student on his first visit to the US, I had been shocked by the

murder of John F. Kennedy (1963) and had heard Bob Dylan’s

premonition at his Cornell concert without really understanding

it, but now it was visibly becoming true: “The

times they are a-changin'.”

These years saw three important mass movements demanding change.

Their slogans were “Black Power”, “Women’s Power”, and “Gay

Power”. In each of these cases, the word “power”, far from

describing a reality, expressed a wish and a goal that needed a

new liberating impetus. “Black liberation” had a long history

dating back to the 19th century, but even in the

later 20th century the African-American community was still very

far from being liberated. For a characterization of that time,

it may be enough to mention the assassination of Martin Luther

King in 1968, the riots in many black ghettos, and the rise of

the “Black Panthers” and other radical groups. Living in

Berkeley and wishing to learn more, I attended a fund-raising

party of the Black Panthers in the home of a wealthy “white”

patron in hills of nearby Oakland.

(4)

In the meantime, like countless others, I eagerly

devoured the bestselling books “Soul

on Ice” by Eldridge Cleaver and the sexologically

interesting “Autobiography

of Malcom X”, who had been murdered by black Muslim fanatics

in 1965. Naturally, I also used every opportunity to discuss the

issues with my black friends. And I really did learn a lot in a

very short time.

The feminist movement also dated back to the 19th

century, but the liberation of women was still very far from

complete. However, the founding of the

The National Organization

for Women (NOW) in 1966

marked the beginning of a new, intensified struggle. The

admission of female students to Yale in 1969 that I had

witnessed firsthand, was a small indication that things were

actually starting to change. This change was accelerated by

nation-wide discussions of popular bestsellers like Betty

Friedan’s “The Feminine

Mystique” (1963), Kate Millet’s “Sexual

Politics” (1970), Germaine Greer’s “The

Female Eunuch”,

(1970), and

Susan Brownmiller‘s

“Against Our Will”

(1975).

Even the “gay liberation movement” dated back to the previous

century, i.e. at least to 1897, when

Magnus Hirschfeld

and others founded the first “gay rights group”, the “Wissenschaftlichhumanitäres

Komité”

in Germany. But “gay liberation” was new to the US, where it had

started in the 1950s with the founding of the

Mattachine Society,

an organization fighting for homosexual civil rights. My later

San Francisco colleague Phyllis Lyon, together with her life

partner Del Martin, had founded the first lesbian organization,

The Daughters of Bilitis,

in 1955. The “Stonewall Riots” in 1969, resulting from a police

raid on a “gay” bar in New York, triggered steadily growing “gay

rights” demonstrations all over the country. In 1973 the

American Psychiatric

Association (APA)

removed the diagnosis “homosexuality” from its handbook. Thus,

practically overnight, millions of formerly mentally sick

“homosexuals” found themselves to be healthy again. It was the

greatest and fastest mass cure in medical history (but no one

received a Nobel Prize for it). Soon San Francisco became the

“gay capital of the world”, and I had the opportunity to observe

it all at close range.

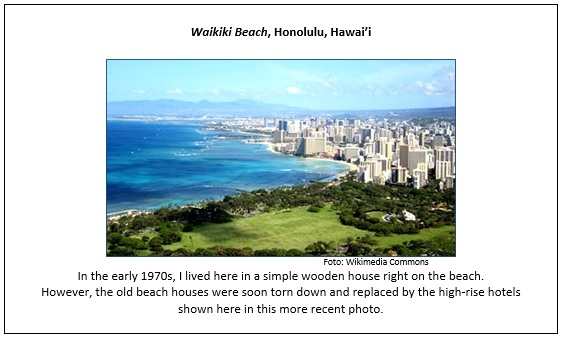

A Textbook of Human Sexuality

At that time, Waikiki had not yet become the high-rise concrete

jungle it is today. Indeed, along the beach there were still

rows of one-story wooden houses on stilts. I rented one of them

and began a relaxing open-ended vacation. After a few months of

swimming, tanning and slowing down, I had absorbed enough of the

“Polynesian spirit” to become curious about the local history

and culture. I therefore began to read about Hawaiian history

and to collect historical recordings of Hawaiian music. I also

explored the city and its neighborhoods. To my surprise, I

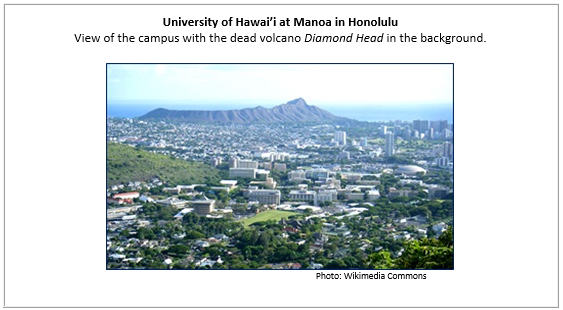

discovered that Honolulu had a

university,

and to my even greater surprise, its Department of Social Work

offered a Master’s degree in “Human Sexuality”.

This was the first time I encountered the study of

“sex” as an academic field in its own right. The program

had an interdisciplinary faculty: Harvey Gochros and David Shore

(social work), Ron Pion (gynecology), Vincent de Feo (anatomy)

and Milton Diamond (biology), who is still on my scientific

advisory board today. It was a lively, innovative group that

invited me to their classes. Trying to make myself useful, I

wrote two chapters for new books by Gochros and Shore - one

about the

historical roots of sexual oppression,

and the other about

youth and sex in Western societies.

When I met their intelligent and highly motivated students, I

noticed, however, that they had to manage without a textbook.

Since I was captivated by the whole idea of “studying sex”, and

since there was no textbook on human sexuality, I decided to

fill this gap and to write one myself. After all, I was

financially independent and had time on my hands, so why

shouldn’t I try?

And obviously, there is no better way to learn about a subject

than to write a textbook for it.

Once I had made the decision, I returned to the “mainland” and

rented an apartment, first

on Nob Hill, later on Cathedral Hill, in San Francisco.

There, I had the convenience of using two great libraries for my

research – the city’s public library and the university library

at UC Berkeley. At a new

Erotic Art Museum I also met the film-maker and photographer

Laird Sutton, who agreed to provide new photo illustrations for

my planned book. At the same time, I kept in close contact with

my Hawaiian colleagues and spent every year several weeks or

even months in Honolulu.

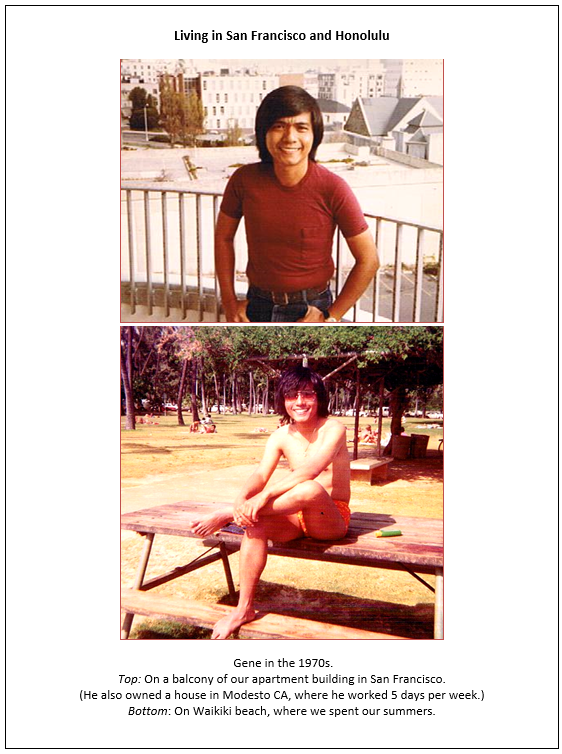

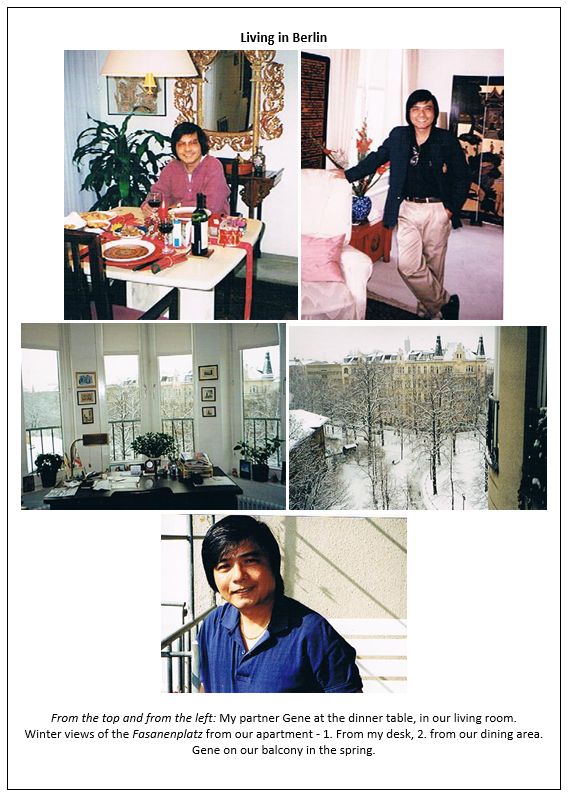

In 1974 I met my partner Gene in San Francisco, with whom I have

been living ever since (we are now looking back at over 42 happy

years together). From that time on, he joined me in Waikiki

every year. As a teacher, he had a summer vacation of 3 months,

and thus, for several years, Honolulu remained our “summer

home”. As the romantic old wooden houses were demolished, we

stayed in various grand beach hotels. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Living in Honolulu, we also made friends outside the academic

environment and regularly attended the Sunday brunches at the

Royal Hawaiian Hotel.

We also took catamaran sailing trips around Oahu, and, needless

to say, explored the other Hawaiian islands, especially the “big

island” Hawai’i with its black beaches and Maui with its old

whaling harbor Lahaina and its moon-like landscape around its

dead volcanoes. And there was another plus: My membership in the

San Francisco Press Club

entitled us to all privileges at the

Outrigger Canoe Club

right on Waikiki Beach. I short, my new life as a self-employed

writer turned out to be very agreeable indeed. And it was with

deep gratitude that I now remembered my envious colleagues in

Heidelberg, who had driven me out of their snakepit and put me

on the pleasant path to this perfect paradise. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

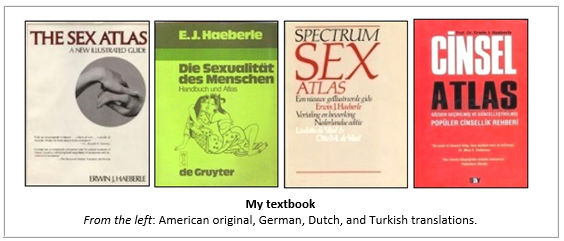

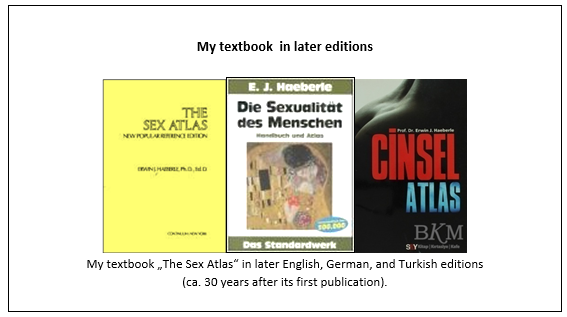

When my book was finally ready for publication, I discovered,

however, that two Stanford professors had beaten me to the

finish line and had written the very first textbook on human

sexuality.

(5)

Apparently, Stanford had also begun to teach the relevant

courses. Thus, my own textbook was only the second. On the other

hand, it had a definite advantage over its competition: Because

of its carefully planned special design and style, it turned out

to be attractive to book clubs and also sold well in regular

bookstores. As a result, my “Sex

Atlas” was commercially just as successful as my “Sex

Book” had been. Moreover, it was translated into three other

languages. But my greatest satisfaction derived from something

else: When the

Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS) celebrated

its 35 anniversary, it named my textbook among the

influential publications

of the preceding 35 years, along with the books by Susan

Brownmiller, Betty Friedan, John Boswell, Michel Foucault and

Masters & Johnson. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

In the meantime, the

Erotic Art Museum had returned its collection to Eberhard

and Phyllis Kronhausen and had developed into a sexological

graduate school – The

Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality (IASHS).

In 1977, I was invited to join this unique, innovative

initiative as a full professor and was given an additional

doctorate (Ed.D), with my textbook being counted as a

dissertation. Among many other things, my employment

there had the advantage of giving me ample time for vacations.

Indeed, I spent my entire summers away from it, first in

Hawai’i, and later in Europe. And Gene always accompanied me.

The Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality in San

Francisco |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The faculty consisted - in addition to myself - of two

additional Methodist ministers (one of them Laird Sutton, whom I

had met earlier), two psychiatrists, two psychologists, four

gynecologists (two of them were also osteopaths and professors

at medical schools), a lawyer, and two pioneering feminists:

Phyllis Lyon, who, with her partner Del Martin, had founded the

first American lesbian organization

“Daughters

of Bilitis”

in 1955, and Maggi Rubenstein,

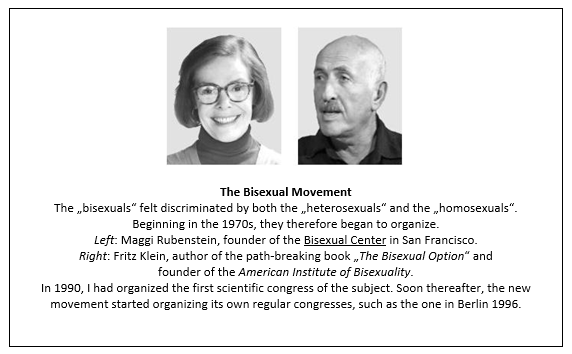

a pioneer of the bisexual movement.

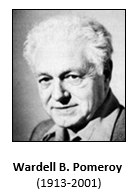

The academic dean was Wardell B. Pomeroy, formerly the closest

collaborator of Alfred C. Kinsey and co-author of the “Kinsey

Reports” of 1948 and 1953. Almost every day I spent many hours

with him talking about every possible angle of human sexual

behavior. From him I learned more about it than from anyone

else.

|

|||

|

In addition to its regular faculty, the Institute had prominent

guest lecturers, some of whom returned several times: The

researchers Frank A. Beach, John Money, Milton Diamond, James W.

Prescott, Vern Bullough, Norma McCoy, Gorm Wagner, Robert

Francoeur, Sally Binford, Fred Whitam, Fang-fu Ruan and

Beverly Whipple, the therapists Albert Ellis, Richard Green,

William H. Masters, David McWhirter and Andrew Mattison, Joan

und Dwight Dixon, Lonnie Barbach, Bernie Zilbergeld,

Bernard Apfelbaum,

Jack Annon,

Fritz Klein, Gina Ogden, Leah Schaefer, William Hartman and

Marilyn Fithian, well-known authors like Gore Vidal, John Rechy,

Edward M. Brecher, Alex Comfort, and Robert Rimmer, the

sociologists Ira Reiss, Martin S. Weinberg, John Gagnon and

William Simon, the great advocate of sexual health education

Mary S. Calderone, the educators Sol Gordon, Lester A.

Kirkendall, William A. Granzig, John De Cecco, Michael Carrera

and Roger Libby, the Sheriff of San Francisco, Richard Hongisto,

the feminists Betty Dodson and Margo St. James and many others. Actually, anyone in the US who had anything important to say about human sexuality sooner or later lectured at our Institute, which became informally known in the US as the “Harvard of sexology”. Never before and nowhere else had there ever been such a gathering of sexological experts. However, we never advanced or advocated a particular point of view or sexual ideology. The life experiences and ideas of our guests were simply too different from each other. Both our faculty and our students had to form their own opinions.

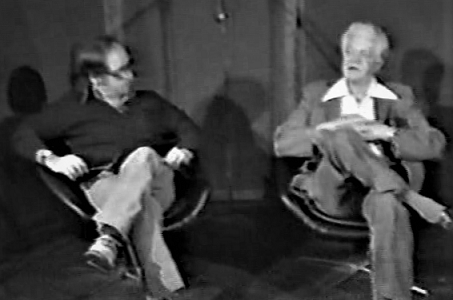

Wardell Pomeroy (on the right) and I teaching a joint seminar in our auditorium

We

followed this general philosophy not only as a matter of

principle, but also as an obligation towards our very special

audience: We accepted only students who already possessed an

academic degree or some professional experience or

certification. Strictly speaking, therefore, the school was an

institute of continuing education (the word “Advanced” in its

title hinted at this.)

Our typical students were fully employed physicians,

psychologists, family therapists, nurses, educators, and social

workers. Over the years, we even had several Catholic priests,

whose tuition was paid by their churches or monasteries. They

all came to our Institute for the purpose of obtaining an

additional qualification that would help them in their duties. Under the circumstances, we worked with a system of trimesters, each lasting four months. During three of these four months, the students attended to their usual work in their home towns, while doing their research projects in their free time and sending in their weekly book reports. All teaching on location in San Francisco was concentrated in the fourth month, when their presence was required for the lecture series and various seminars. |

|||

|

Unfortunately, once I had returned to Germany in 1988 and, one

year later, had decided to stay there, I lost contact to the

Institute, because new challenges in Germany and China took up

all of my time. Grateful as I was to my former workplace, I

remained - without pay - on the list of faculty, as did other

colleagues who had also left for other positions. Occasionally,

I even answered requests from new students, but, on the whole, I

no longer followed the developments in San Francisco. I did pay

a brief visit around my 70th birthday, but, at that

time,

because of an academic vacation, I did not find any students

there. Only the top administrators were present. For me

especially, it was a very sentimental reunion, because, as it

turned out, most of my former colleagues had died, and others,

like me, had moved on to other places. Even many of our

prominent guest lecturers were no longer among the living and

had joined “the truly silent majority”.

Thus, it was inevitable that we few remaining “old war

horses” became nostalgic and talked mostly about our past “days

of glory”.

|

|||

|

Now, once again many years later, I hear from some of my own

former doctoral students that, in the course of time, the

Institute had undergone substantial changes. Indeed, as I

understand it, its building has been sold to be replaced by a

new high-rise of luxury apartments. It seems, therefore, that

the Institute has lost its San Francisco location. I have not

been able to ascertain if, where, and in which form it will

continue to exist. When I worked there, however, it was unique

and far ahead of its time. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

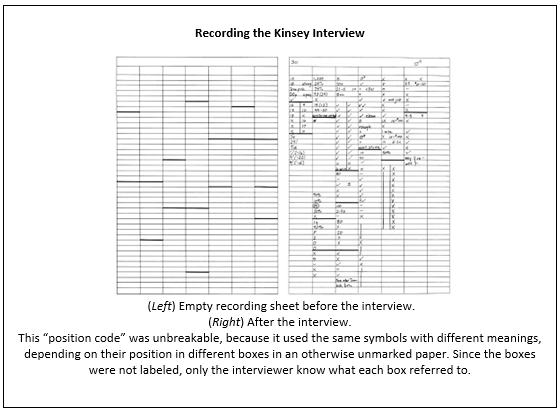

When the interview was conducted properly, the entire sexual

life of an individual, with all of its details, fit on a single

recording sheet. There were only two exceptions: For the sex

histories of prostitutes and of those with very extensive

homosexual experiences Kinsey and Pomeroy (and later Gebhard)

used an additional sheet. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

2. SAR |

|||

|

|

|||

|

3. Documentary Films

4. Video documentation of our classes

5. Visitors and Visits |

|||

|

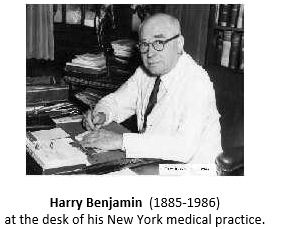

New York City offered me the chance for three important visits: In mid-town Manhattan, Bob Guccione, the editor of the magazine „Penthouse“, invited me to his well-guarded townhouse, and on the Lower East Side I visited John Gagnon in his spacious loft. Most importantly, however, I met Harry Benjamin, an ardent opera fan like myself. As a young man in Berlin, he had seen and heard Enrico Caruso on the stage (as Radames in “Aida”). At a Berlin opera ball, he had danced with Geraldine Farrar, who had started her career in that city, but then moved to New York’s Metropolitan Opera. There, she was much admired not only for her singing, but perhaps even more for her beauty. Once Benjamin had finally settled in New York in 1915, he was able to witness her many triumphs at the MET (for example as the first ”Butterfly”), and of course, he also followed Enrico Caruso’s career on the same stage. Eventually, one of the greatest opera stars of all time became his patient - the “blonde bombshell” Maria Jeritza, the first “Ariadne” of Richard Strauss and Puccini’s favorite “Tosca”. Benjamin gave me his correspondence with Hirschfeld as well as other historical materials in the hope that, one day, I would be able to find a safe place for them in Berlin. And indeed, today they are housed in the Haeberle-Hirschfeld-Archive of Humboldt University. On the occasion of his 100th birthday, I conducted an interview with him for a German journal of sexual medicine.

|

|||

|

In 1980, the American

Association of Sex Educators, Counselors and Therapists (AASECT)

invited

me to speak at their annual conference in Washington DC. I chose

a subject then still hardly discussed by sexologists – the

„Stigmata

of Degeneration: Prisoner Markings in Nazi Concentration Camps”.

For this, I also prepared two large display boards and

donated one of them to the Holocaust

Memorial Council, which

sent me a letter of thanks. The lecture was later published in

the Journal of Homosexuality.

At that time I also indirectly renewed an older connection: In

addition to my work at our Institute in San Francisco, I taught

a class on human sexuality at the

UC Berkeley Extension.

This was something I really enjoyed. My students were

enthusiastic and wrote very flattering evaluations. I gratefully

continued the class for several semesters until increasing

travels and other duties began to interfere and, to my immense

regret, forced me to discontinue.

In those days I often flew to New York, where I still worked as

a part-time editor for my friend Werner M. Linz.

One day, an older German immigrant visited me in

my office and introduced himself as Richard Plant, a former

private secretary of Klaus Mann (the openly gay son of Thomas

Mann). Plant wanted to write a

book on the Nazi persecution of homosexuals and offer it to us

for publication. Needless to

say, I strongly urged him to do so and to keep in touch, because

I felt that such a publication was long overdue and would also

be commercially successful. Unfortunately, we never heard from

him again. However, his proposal lingered in my mind, and I

finally decided to use whatever material was available at the

time for a journal article “Swastika,

Pink Triangle and Yellow Star - The Destruction of Sexology and

the Persecution of Homosexuals in Nazi Germany. It

appeared in 1981 and was eventually included in an anthology “Hidden

from History”. Plant‘s book was published five years later

by another company:

The Pink Triangle: The Nazi War Against Homosexuals, New

York 1986. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

At this point I would like to leap ahead for a brief summary of

a memorable episode: Sometime in the early 1990’s, when I was

already working in Berlin, my old publisher friend Werner Linz

invited me for a few weeks to his home in Rye, N.Y. Once there,

I used the opportunity for a “sentimental journey” back to

Yale. In the meantime, of course, the

professors I had known were no longer available. Most of them

had died, others retired, and my contemporary fellow students

and researchers had found positions in other universities.

Nevertheless, I felt a need to return at least once to the place

that had been so important for my career. Moreover, I wanted to

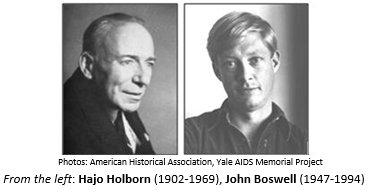

meet the younger cultural historian John Boswell, whose books

had greatly impressed me. He had just been appointed head of the

Yale history department, and thus I found him in the middle of

his move to a new office. He was an impressive, somewhat

idiosyncratic, but very likable person. His all-too-early death

was a great loss to everyone interested in the history of

homosexuality. We talked at

great length about his various studies and his plans for the

future. We also discussed the general situation of the

university, which had begun to fortify itself against intrusions

from the impoverished, deteriorating city of New Haven. On

campus, the formerly open, picturesque passage ways and inner

courtyards were now closed with huge iron gates that could be

opened only with personal keys. At the

Hall of Graduate Studies,

where, for three years, I had eaten my daily meals, I found

something new posted near the entrance - a weekly crime report,

the „Yale Police Log“,

which listed the break-ins, burglaries, thefts, and assaults of

the preceding seven days. The whole situation was depressing.

Boswell, being relatively young, had never known the idyllic

conditions that I had enjoyed a quarter-century earlier. At that

time, and in the same rooms, I had often visited the Berlin-born

historian Hajo Holborn, who had been very helpful to me as a

supporter and advisor. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

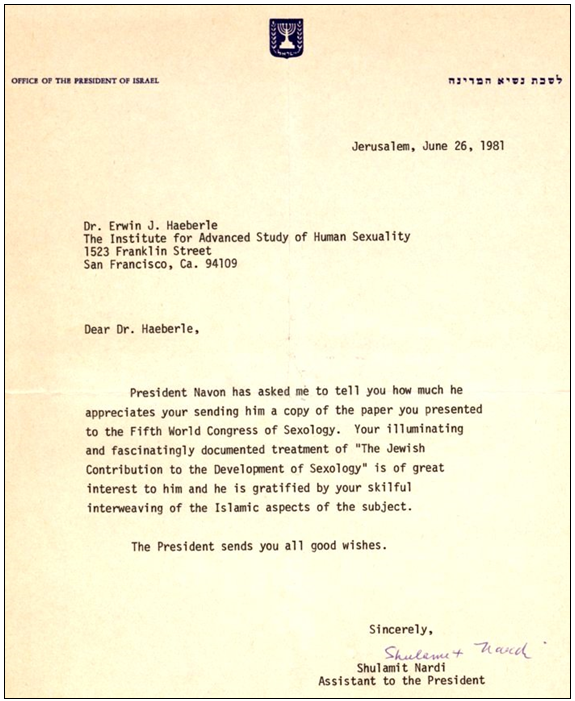

World Congress of Sexology in Jerusalem

This early, tragic history of our field was largely forgotten

even in Germany, and practically unknown in the US. Because

of my German background, however, I had learned at least some

basic facts about it and was eager to share them with interested

colleagues at the World

Congress of Sexology in Jerusalem 1981. My presentation was

very well received and later published in the congress

proceedings. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

In advance of the congress, the

International Academy of Sex Research

(IASR)

had organized a meeting for its members in Haifa, which I

eagerly attended, because I wanted to seize the opportunity to

travel around Israel in search of historical materials. Yohanan

Meroz, the former Ambassador of Israel in Germany and son of Max

Marcuse, had given me several promising addresses. And, indeed,

I found such materials and delivered them to the Kinsey

Institute when I became one of its paid research associates.

Traveling by bus, I visited a number of elderly German

immigrants (“Jeckes”) who had escaped Nazi persecution by

moving to what was then called Palestine. For example, in

Jerusalem I met a photographer, a charming, unmarried old lady,

who had taken Max Marcuse’s portraits and now lived very happily

in a simple flat. In a Kibbutz near the Lebanese border, I

visited an 80-year old woman, who, as an enthusiastic Zionist,

had left Freiburg Br. - of all places - as early as 1929.

Obviously, we had a lot to talk about the developments in the

Black Forest since then. She invited me to a typical German

afternoon coffee with cake and whipped cream. Thus, we had a

wonderful time sitting in front of her ample library shelves

with the collected works of Goethe, Schiller, and Heine. She

still clung to the socialist ideals of her youth and bitterly

criticized the Likud and Menachem Begin, who was about to win

the next election. In Haifa I met an elderly Jewish couple that

had barely escaped from Berlin, but were still proud of their

German background. In Tel Aviv I lost my way and asked

passers-by in English for the next taxi stand. However, I only

met with blank stares. I then repeated my question in German and

was immediately given the right answer. In the meantime, of

course, the old “Jeckes” have died, the German influence has

waned, and Israel has acquired a very different character.

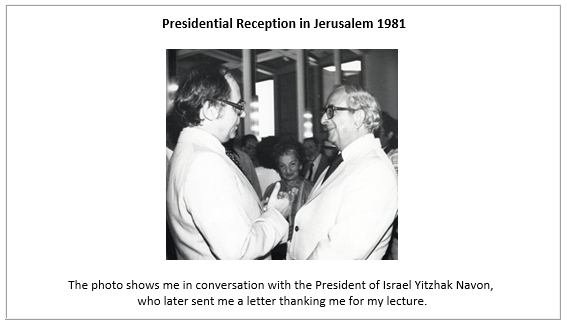

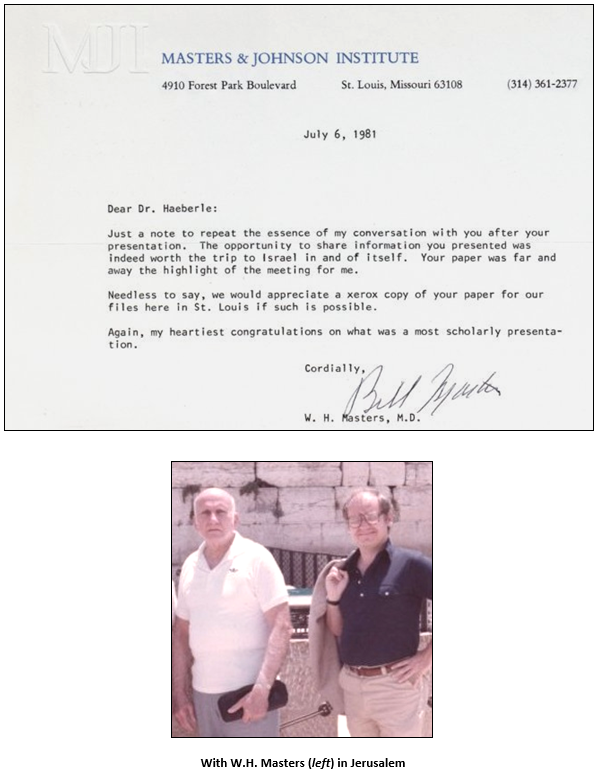

For me, my contribution to the congress brought two important

rewards: Both the president of Israel,

Yitzhak Navon

(1921-2015),

and the most prominent American sex researcher and therapist

William A. Masters

(1915-2001)

sent me letters of thanks.

I did not have another opportunity to return to Israel,

but in the following years I was lucky enough to visit Masters

and his institute twice in St. Louis. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

Here something very personal:

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

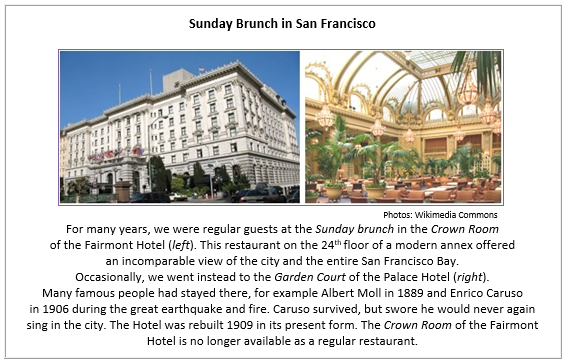

A few years later, I moved to Cathedral Hill. From there, we

took the cable car at its terminal California Street/Van Ness

Avenue and, after

an exciting ride, were delivered right at the door of the

Fairmont - always a delightful experience in itself.

Occasionally, we also went to the historical „Garden

Court“ at the Palace

Hotel on Market Street. These several

hundred unforgettable Sundays - always in very good company -

are among my most cherished memories.

At the Kinsey Institute |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Walking around the institute’s library, I discovered rows and

rows of bookshelves with old German sexological publications. As

it turned out, however, Kinsey had not known German, and had,

for his “Reports”, used just a few short excerpts in

translation.

Nevertheless, he had managed to collect practically the entire

literature written before 1933 by our German sexological pioneers – books, journals, pamphlets,

posters, newspaper articles, letters, and more. Just a few

months before, I myself had used my limited knowledge of this

early phase of sexology for my presentation in Jerusalem, but I

had never realized how vast its accomplishments had been and how

many authors had contributed to them. Apparently Kinsey,

although unable to read his own collection, had known that it

would be important for others. Therefore, from the very

beginning, he had tried to establish his library as a very

broad, serious and lasting basis for sexuality studies of all

kinds. Standing in front of this unexpected treasure, I was

overwhelmed and deeply impressed by Kinsey’s foresight,

thoroughness and seriousness as a researcher. From that moment

on I saw him in a new light as a truly great scientists and a

model professor in the best academic tradition.

When I talked with Paul Gebhard about this, he confirmed my

impression and added that, no staff member had ever read the

German section of the library. He therefore decided, right on

the spot, to give me a salaried position as a research associate

at the Kinsey Institute. I

also did not hesitate and immediately made copies of

the most important German documents I found. These I took back

home with me and, from then on for several years, I regularly

commuted to

Bloomington, making ever more copies and working on

them in San Francisco, where I continued my job at our training

Institute. Beginning at that time, half of my salary was paid by

Indiana University.

Looking more closely at my German material, I soon realized that

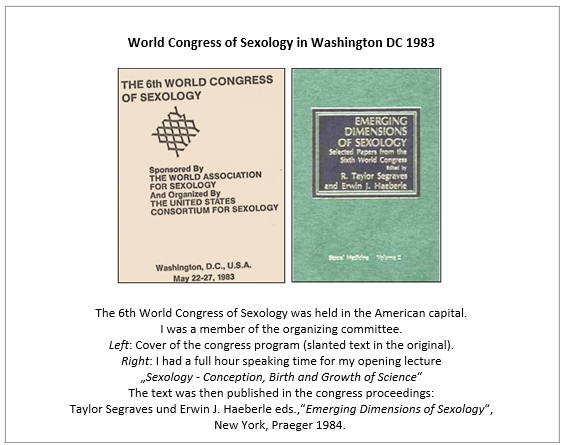

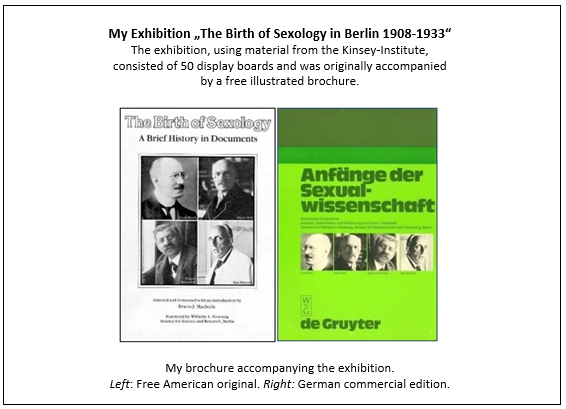

1983 would mark a triple anniversary:

1. A traveling exhibition

In Washington DC, I was assigned a 60-minute opening speech on

the subject, and the manuscript was then printed in the congress

proceedings, which I edited with my medical colleague Taylor

Segraves. Together with my exhibition, it was a “double whammy”

and a great success. More importantly, in the following years,

my exhibition travelled to other countries – Germany, Denmark,

Sweden, Switzerland, the crown colony Hong Kong, and China.

Everywhere it was shown, it produced favorable reviews in the

press, including the newspapers in China. I finally donated it

to my Chinese colleague Liu Dalin for his museums in Shanghai

and other Chinese cities. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

In Germany, my exhibition was shown in Hamburg, Kiel, Oldenburg,

and Marburg, but in Berlin itself nobody was interested. Thus,

it never had a chance to inform and educate the universities,

the opinion makers, and a wider audience in that city. In a

sadly ironic twist, a few years later Berlin once again became

the German capital, but to this day, there is still no one who

understands or appreciates the intentions of its sexological

pioneers. As I eventually found out to my surprise, dismay and

exasperation, in Berlin there is no interest whatsoever in

rebuilding anything like Hirschfeld’s multidisciplinary and

globally oriented institute. Instead, the in Berlin formerly

comprehensive effort has broken up into fragments.

Sub-disciplines like sexual medicine, gender studies,

homosexuality studies, and sex education now jealously guard

their independence. Instead of striving for a common

“centralized standpoint”, as Iwan Bloch had called it, they now

prefer to farm their own separate little acres.

As a result, they are losing their collective “punch” and

are, slowly but surely, drifting into scientific and social

insignificance. Unfortunately, this trend has now also reached

the United States. Kinsey himself had carefully avoided any

close connection to medical institutions. His research had

always tried to cover all aspects of sexual behavior. Later, in

anticipation of possible centrifugal tendencies, the institute

expressly tried to forestall these by changing its name to “Kinsey

Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction”.

However, this preemptive measure proved to be futile: Today,

Indiana University, like many other universities, also has in an

independent Department of Gender Studies. The unified approach

used by the great German pioneers and their worthy American

successor Kinsey is increasing being lost. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

Considering its glorious past, the situation of sexology in

Germany is especially depressing: In the public mind,

Hirschfeld’s role in the establishment of a new,

multidisciplinary science has been reduced to little more than

that of a former German “gay activist”. Hirschfeld, the

innovator, motivator and fearless reformer in many fields,

author of books and articles on many different subjects, journal

editor, congress organizer, educator and lecturer, fighter for

women’s rights, defender of all sexual minorities, film

initiator and collaborator, institute founder, library

builder, museum director, always curious collector of erotica

and ethnological artifacts, master organizer and internationally

well-connected world traveler, remains largely unknown in the

country of his birth.

2. An essay on “obscene” photographs |

|||

|

|

|||

|

3. An unwritten book

No one, on either side of the Atlantic, cared a whit that there

were only very few survivors left, who could be interviewed

about the pioneering phase of sexology. Soon thereafter, they

also had died. Anyway, in the end I was never given the chance

to put me whole energy into this major project. To this day,

there is no comprehensive history of sexology, and it is highly

unlikely that it will be written soon.

(7)

There is, however, a solid first partial overview

published in 1994 by

Vern Bullough.

Before his death in 2006, he gave the copyright to me, and I therefore made it available in my Archive’s online

library: „Science

in the Bedroom“

(also in Spanish: „Ciencia

en la alcoba“)

And, over the years, I myself was able to make the occasional

contributions now included in this book (see Content).

It was clear to me, however, that a serious historical study of

sexology had to begin at least with the “age of enlightenment“

in Europe, especially in France and the United Kingdom.

The Déclaration

universelle des droits de l'homme of

1789 and the Code

pénal

of

1791 for the first time removed all religious influences from

the criminal law (reconfirmed in

Napoléon‘s code of 1810).

Because of Napoléon’s conquests,

this new criminal code soon also began to apply in other parts

of Europe. Thus, for example, male homosexual contact was no

longer punishable, even in some parts of Germany (Bavaria,

Württemberg, Baden, and Hannover).

This, in turn, influenced the German public discussion of

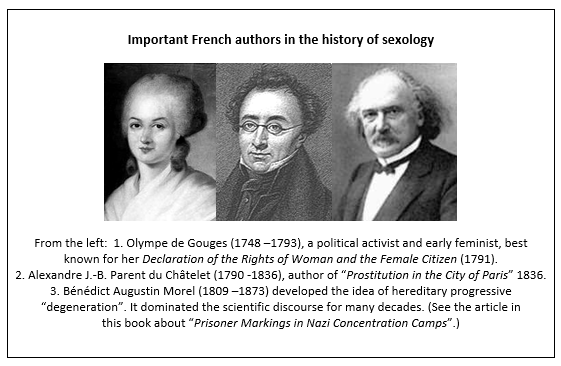

the issue. Further early French historical sources were the

works of Rousseau, de Sade, and Olympe de Gouges, a feminist who

demanded equal rights for women, and who, in 1793, was executed

by guillotine. Later important writings were those of the

psychiatrist Bénedict A. Morel, the physician

and public health pioneer A. J. B Parent -

du Châtelet

, the writer Rémy de Gourmont (The

Natural Philosphy of Love), the neurologist Jean-Martin

Charcot and eventually Simone de Beauvoir and Michel Foucault.

All of these names are merely hints at the larger “real story”

behind them.

Even more interesting was the older English literature -

from Mary Wollstonecraft to Jeremy Bentham, Thomas

Malthus and Francis Place to the Malthusian League

and Robert Drysdale. This would

have required an investigation of the role played by censorship

in the development of our science.

(Even today sex research is not really free, but

that is a subject of another study.) Another important author in

this context was the philosopher John Stuart Mill, whose many

writings, and especially his work

On Liberty,

written with the substantial, if unacknowledged contribution

of his wife Harriet Taylor Mill, emphasized the importance of

individual freedom. The interaction between the forces of sexual

liberation and sexual repression in 19th and 20th

century Britain would have needed special attention. (By the

way, here we’ll find Marx and Engels in the reactionary camp.) |

|||

|

|

|||

|

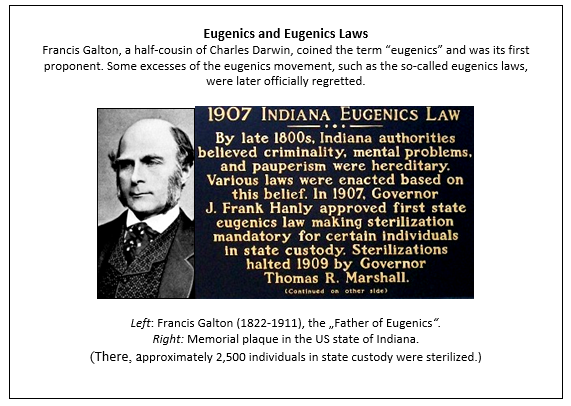

It goes without saying that I would have put my whole study into

the context of two revolutions, which both had begun in England:

1. The industrial revolution with its enormous social and sexual

consequences, and

2. The scientific revolution started by Charles Darwin’s

biological study of 1859 “The

Origin of Species”,

in which he described and offered proof of the process of

evolution.

For decades, this epochal work led to heated controversies,

misunderstandings, and false interpretations. One of them was

the theory of „social Darwinism“.

This ideology misinterpreted the principle of the „survival

of the fittest“

(i.e. of the best adapted) as the „survival

of the strongest“,

which, from the standpoint of biology, is utter nonsense, of

course. As we all know, the large, strong dinosaurs did not

survive the then small and weak mammals, which were able to

adapt to the changed climatic conditions. Nevertheless, the

nonsense of social Darwinism continued to haunt political and

economic discussions well into the 20th century,

especially outside of England. One example was a new,

pseudoscientific racism, which no longer used religious or

simply xenophobic arguments, but invented various “inferior”

races, including an alleged Jewish race that supposedly

threatened the health and order of society. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

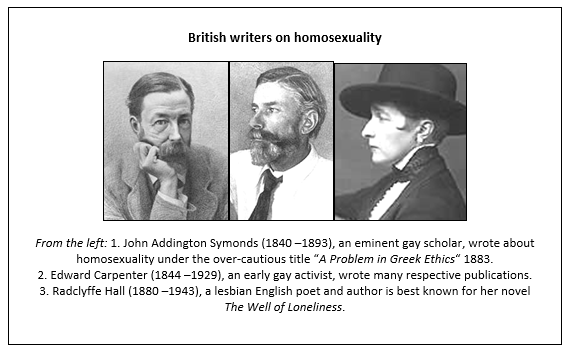

The cultural history of the United Kingdom offers numerous,

embarrassing examples of sexual ignorance, prudery, and

hypocrisy. Well-known homosexual victims were Oscar Wilde in the

19th and Alan Turing in the 20th century. As far as

the social attitudes toward homosexuals are concerned, the

writings of John Addington Symonds, Edward Carpenter,

E. M. Forster and Radclyffe Hall were milestones on the

way to greater tolerance. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

The books of the most important British author on sexual

questions, Havelock Ellis, could not be sold in his own country.

His „Studies

in the Psychology of Sex“

had to be published in the USA, but even there were legally

accessible only to physicians. Eventually, however, Norman

Haire, a friend of Hirschfeld’s, managed to gain some influence

as a reformer in the United Kingdom. Haire closely collaborated

with the feminist Dora Russell, who, together with her husband,

the philosopher Bertrand Russell, consistently and very

energetically demanded sexual reform.

A highlight of their collaboration was the congress of

the World

League for Sexual Reform (WLSR)

.

The cultural history of the US also provides interesting

examples of a sexually repressive ideology - the

anti-masturbation campaigns of

Graham and Kellogg

,

the originators

of „Graham

Crackers“

und „Kellogg’s

Corn Flakes“.

These “health foods” supposedly dampened the sex drive and

thereby reduced the dangers of masturbation.

On the other hand, the 19th century also saw the birth of

the American women’s movement, which, in the 20th

century, became very important for the progress of our science.

Unfortunately, the general population suffered the devastating

effects of Anthony

Comstock’s

crusade against “obscenity”. He and his allies in the US

congress established a regular “reign of terror”

aimed at preventing any kind of sexual information and

education. Indeed, their

negative influence could still be felt in the 1950s, when

congress pressured the

Rockefeller Foundation to

end its support of Kinsey’s research.

It must be acknowledged, however, that the sexologically

interested Rockefellers had already been sabotaged for years by

the “scientific establishment”.

(8)

On the other hand, there also had been independent

American sexological pioneers, such as the physiologist and

educator Winfield Scott Hall (1861-1942) the gynecologist Robert

Latou Dickinson (1861-1950), and Margaret

Sanger the

tireless fighter for contraception.

Another name deserving to be mentioned is that of Hugo

Gernsback (1884-1967), who published the popular periodical „Sexology

- The Magazine of Sex Science“ (1933-1967).

This small, cheap magazine tried to describe and explain

the latest serious research and often found qualified original

authors. For example, from August 1949 to August 1951 it

published, in installments,

René Guyon‘s otherwise

unavailable study „The

Sexual Problem in the Historical Period“.

Finally, one should not forget the largest educational

bestseller before WW II: „Ideal

Marriage“,

written by the Dutch gynecologist T. H. van de Velde. Although

listed in the Catholic „index of forbidden books”, it was, for

several decades, the most widely read sexological book in both

the US and Europe.

(By the way, the English word

„sexology“

appeared as early

as 1867 in the title of an American book by Elizabeth Osgood

Goodrich Willard: “Sexology

as the Philosophy of Life: Implying Social Organization and

Government”.

However, the text does not use the term in our modern sense of

„sex research“, but refers to a mysterious fundamental life

force similar to the Chinese Yin and Yang. The whole book

is a philosophical-moralistic pamphlet aimed at “improving the

world” by persuading people to submit to the postulated supreme,

true ordering principle of nature.

It is unclear whether the author actually coined the word

“sexology” herself or whether she borrowed it from another,

still unknown writer. However, I am sure I would have found

out.)

Summing up: The developments in Great Britain and the USA had a

very special character of their own: They were torn between a

libertarian pioneer spirit and the heritage of Puritanism.

Here, I can only hint at this. In any case, I would have

written my historical study in English and thus would have

reached many readers who, even now, know nothing of this

history. As for the “true” ancestors of our science, nothing

definite can be said. After all, the „golden age of Islam“ (ca.

800 -1300 A.D.) had already produced a voluminous sexological

literature in the Middle East and even in Europe, i.e. in

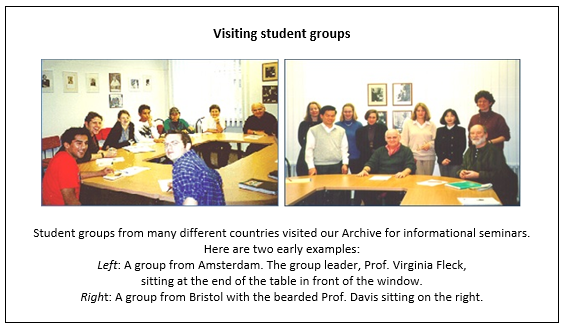

Andalusia (al-Andalus).