|

A SOCIOLOGICAL THEORY OF HUMAN SEXUALITY

SOCIOLOGY: A SINGULAR PERSPECTIVE

BASIC ASSUMPTIONS UNDERLYING THE PROPOSITIONS

Assumption One

Assumption Two

Assumption Three

A NARRATIVE STATEMENT OF THE THEORY

Sexual Bonding: Antecedents of Kinship and Gender

Sexuality and the Power of Each Gender

Sexuality and Ideology

Social Change and Societal Linkages

THE PROPOSITIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE THEORY

Propositions on Sexual Bonding as the Antecedent of Kinship and Gender roles

Propositions on Sexuality and the Power of Each Gender

Propositions on Ideology and Sexuality

Propositions on Social Change and Sexuality

THE PROPOSITIONS: THEIR UNITY AND DERIVATION

CODA

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

SOCIOLOGY: A SINGULAR PERSPECTIVE

The reader can start to relax now. We are nearing the end of our journey. We have one final task: to integrate and specify, as best we can, the sociological explanation of human sexuality developed in this book. To be sure, this is no mean task. But it is essential to present succinctly an overview of the key features of my theoretical position. Although at this stage in our theoretical development there will of necessity be many gaps, it is still crucial to leave the reader with as clear a perspective as possible concerning the sociological explanation of human sexuality developed in this book. The ground must be prepared for future theoretical growth.

I will seek to accomplish this goal in three phases. First, I will present briefly three basic assumptions that underlie my sociological approach. Secondly, I will relate in narrative form the sociological theory of sexuality that I have developed. This will be an informal, discursive presentation. I will conclude this section with a summary diagram revealing the broad overview of the key elements involved in this sociological explanation. This narrative account will be divided into four sections relevant to the three linkage areas and to social change.

The third phase consists of a more precise, formal presentation of the same explanatory schema in the format of 25 explanatory propositions. These propositions will contain the bulk of the reasoning and empirical relationships that are derivable from the narrative account of my sociological theory. I will organize these 25 propositions into the same four major divisions as were present in the narrative account. Each of these four propositional sets will contain interrelated propositions.

By following this mode of increasingly specific explanation, I mean to satisfy the curiosity of the more general rather as well as that of the more specific professional.

BASIC ASSUMPTIONS UNDERLYING THE PROPOSITIONS

All theoretical explanations are based upon certain, often unspoken, assumptions about the world in which we live. My theoretical approach is no exception. Most of these assumptions have been mentioned at least briefly, but it is useful to group them together in one place.

Assumption One

I assume that the scientific approach is one way to understand social reality. This does not rule out the possibility of religious or other philosophical approaches to reality. Rather, it asserts that I am founding my explanation in the scientific realm. By science I mean systematized knowledge based upon observation and experimentation that is directed toward explaining and predicting the phenomenon studied. Accordingly, it is assumed here that there is an objective reality that can be scientifically explained. The epigraph to this book clearly states my view on this matter. Lest you think this is an incontestable assumption, recall that philosophers have debated this very point for centuries despite the fact that most Westerners fully accept this assumption.

Assumption Two

I accept a modified hedonistic view of human behavior. I assume that all human behavior is motivated by the pursuit of pleasure and the avoidance of pain. The important point here is that all behavior is self-oriented. However, I modify the more radical hedonistic perspective by asserting that people's selves vary in the degree to which they incorporate the welfare of others as a source of pleasure and pain. Social life is based upon our ability to internalize the welfare of others to the point that we feel rewarded when they are rewarded. It is by such absorption of others into ourselves that the boundaries separating people are partially removed. Our most important social relationships attempt to unite people in just this way. Most of us learn in our sexual behavior to incorporate at least partially the pleasures of others as our own pleasures. Even so, it is in good part our basic nature as creatures who pursue self-oriented pleasures of all sorts that makes sexuality so important to us.

Assumption Three

I assume that societal-level causes are major influences on our sexual lifestyles. I further assume that factors such as biological and psychological causes are central when comparing individuals but not of first importance when comparing societies. For example, there is no a priori reason to presume that one society is different from another in the biological makeup of its population. Thus, I conclude that among societies, differences in sexuality will be due to sociological forces. Hence, in the examination of lifestyles of societies or groups, sociology is clearly central to any explanation.

I am sure that I must be making other philosophical assumptions, but the three stated here are the most obvious ones that underlie my sociological explanation of sexuality.

A NARRATIVE STATEMENT OF THE THEORY

Sexual Bonding:

Antecedents of Kinship and Gender

Once I asserted the sociological or societal level as the chosen level of explanation I needed to formulate a clear definition of sexuality from that perspective. I defined sexuality as consisting of those shared cultural scripts that are designed to produce erotic arousal that in turn will produce genital response. The idea behind this definition is not just that sexuality is learned but that it is learned from the societal scripting of the erotic life of individuals.

Here and throughout the book I am searching for broad, universally valid definitions, concepts, and explanations. It is equally important, though, to explain the variation regarding how societies operate within these universal parameters. I have used, among other things, my causal analyses of the Standard Sample in various chapters to help in arriving at explanations of such societal variations.

I further explained human sexuality by proposing that for all societies genital response most often leads to significant levels of physical pleasure and self-disclosure. These two consequences give sexuality importance in all societies regardless of the level of socially acceptable sexual permissiveness. This importance stems from the interpersonal-bonding potential produced by the pleasure and disclosure characteristics of sexuality. All societies judge interpersonal bonding to be important, for such bonding is the structural foundation of a society. Societies organize the bonding power of sexuality so as to enhance socially desired relationships and avoid socially undesired relationships.

To illustrate: sexual bonding is encouraged in marital relations that tie together individuals from different social groups, whereas sexual bonding is discouraged in parent-child relationships to avoid role conflict and jealousy and also to encourage young people to seek mates from other groups and thereby build alliances that can be helpful.1 In the extramarital area, some societies stress the pleasure aspects of sexuality in order to keep self-disclosure to a minimum and thereby discourage any stable, personal bonding outside of marriage.2 In some societies, like the Sambia, homosexuality is encouraged as part of a desired matebonding process and a preparation for heterosexuality. Only a few societies attempt to discourage sexuality in all settings outside of marriage. Not so long ago, the United States was one of those societies.

The rudimentary forms of kinship can be viewed as deriving from and being supported by the sexual bonding of individuals who nurture offspring. The socially defined descent relationship between children and parents can be seen as an outcome of a stable sexual relationship between the parents. In that sense, the tie to the offspring develops from those who remain to socialize the child. Those stable adults would most often include the biological mother of the child and also her mate. It is the stable sexual bonding of the parents that I conceptualize as the social support network into which the newborn child is placed. Stability does not necessitate a life time but it does imply a number of years. Other adults, such as the mother's brother or the mother's mother, may be very important once the production of children begins, but it is the presence of a stable sexual mate that establishes the relationship basis for the start of parenthood.

The reader will recall that I do not view the importance of the sexual relationship as reducible simply to its reproductive consequences. In fact, I have stressed the greater importance of the consequences of physical pleasure and self-disclosure. Sexuality can bond and will be judged as important even when there are not any reproductive consequences. Surely homosexuality has bonding power without reproductive outcomes. It is the potential of sexuality to create lasting human relationships that makes it likely that couples will stay together long enough to produce and nurture a newborn. The pleasure and disclosure aspects of sexuality can act as a catalyst to the development of increasing self-disclosures regarding shared nonsexual pleasures that can further create a stable bond. In that sense the bonding nature of sexuality leads to its high valuation and to the possibility of reproduction occurring and conventional kinship ties developing. In this fashion, sexual bonding helps creates the support system needed for the newborn to survive.

As the kinship system with its generational ties develops, gender roles also are formed. In order to accomplish the nurturance of the newborn and maintain the satisfying bonds derived from the sexual relationship, some pattern of task assignment for male and female must be developed. It is through this process of the social assignment of task and power relationships that the rudiments of societal gender roles are hypothesized to be formed.

Sexuality and the Power of Each Gender

One outcome of this desire to maintain important sexual bonds is the linkage of sexuality in marriage to power and jealousy. The ability to control sexuality depends on one's power. Power, in turn, depends on one's role in the major institutions: the political, religious, family, and economic institutions. The specific roles in the family assigned to males and females can define the degree of freedom each gender has to participate in other institutional roles and thereby restrict or expand that gender's potential societal power. In effect, the societal sculpturing of gender roles that centers females more than males in the family institution is the key basis of the lesser power females are given in virtually all the other societal institutions. Nevertheless, we should not lose sight of the power inherent in kinship ties themselves. The greater the kin ties for women, the less likely that women will be sexually abused. This is so because the woman's kin will offer unified protection against such abuse. This can be noted particularly in matrilineal societies.

Power influences access to the important sexual possibilities in a society. Power legitimates access to whatever pleasures of life are present in that culture. Thus, the greater the power of one gender, the greater that gender's sexual rights in that society. These greater sexual rights of men may show up in the increased likelihood of sexual abuse of women. In addition, the powerful have more ability to organize gender roles in ways that further stabilize their power in the basic institutions. This has typically been accomplished by encouraging men to participate more in the political and economic systems and women more in the family system. In addition, male power in other institutions may flow over into the kinship roles and strengthen their influence even in marital and family relationships.

Sexuality and Ideology

As a society stabilizes its institutional structure, it will develop a set of deeply rooted beliefs about the nature of human beings. These beliefs are the logical foundations of more specific notions of good and bad, normal and abnormal. These firmly held beliefs about human nature are what we have called ideologies. Such ideologies will have relevance to all the major institutions in a society and to all important relationships, including, of course, sexual relationships. Thus, sexuality will have an ideological base deriving from its ideological linkages in society. The basic dimensions of sexual ideologies revolve about levels of gender equality and sexual permissiveness. These are the two basic issues that men and women face everywhere in their sexual relationships; that is, how equal will the relationship be, and how much sexual permissiveness will each gender be allowed. Differences in sexual ideology and in power are linked to different attitudes toward erotica. In this sense, attitudes toward erotica are linked to one's position in a social system.

Heterosexuality and homosexuality are interdependent in that one is defined in terms of the other. Homosexuality can be defined as another acceptable part of sexuality that is integrated with the kinship and gender concepts of the society, or it can be defined as a competitive pathway that must be guarded against. Contrast the Sambia and the United States to visualize these two alternatives. In both cases, homosexuality and heterosexuality are defined in terms of each other, but with quite different resolutions.

The centrality of heterosexuality in human societies is directly derivable from its linkages with kinship and gender roles. Acceptable sexual behavior, whether it be homosexual or heterosexual, is fundamentally defined in terms of its degree of compatibility with the basic kinship and gender conceptions of a society.

Social Change and Societal Linkages

In sum, then, the universal linkages of sexuality in society occur in the areas of kinship, power, and ideology. As noted, in kinship, the linkages to sexuality will be found in the jealousy mechanisms protecting sexual bonding in marriage. In the power area the crucial sexual linkages are to gender roles. Such gender roles are seen as developing out of the kinship structure, which in turn was derived from sexual bonding. Finally, the specific ideological areas involving sexuality will concern notions of normality centering upon equality and permissiveness, for those issues are central in kinship and gender relationships. So the linkages of sexuality to kinship, power, and ideology are here specified as being ties to marital jealousy, gender roles, and concepts of sexual normality. It is important to be explicit here because kinship, power, and ideology are broad aspects of society, and it is well to be more precise regarding exactly where the linkages to sexuality will be found. It is by means of an examination of these universal linkage areas that the specific explanations of sexuality are derived. Through these explanations we can understand the variations that occur in these linkage areas in different societies.

The kinship, power, and ideology linkages of sexuality are, of course, causally tied to other important parts of the social system. In particular, the economic institution, consisting of the type of subsistence (hunting, agriculture, industry), is influential in terms of change. This is so because the economic institution is viewed in rational terms as a means to the end of providing subsistence. Accordingly, societies are often willing to change the economic system if new subsistence opportunities present themselves. Change is not quite as easy in the political, religious, and family institutions.3

I do not deny that the causal relationship between parts of the society may be a two-way relationship and that this eventually needs to be carefully examined. This is so, even though most of my diagrams and other parts of my explanation have been presented as predominantly one-way processes. I do believe, however, that the direction I have posited is the most powerful. However, that does not deny the possibility of a reverse influence of a more minor sort in at least some areas. The relative power of each causal direction is a matter for empirical study. Changes in kinship can influence the economic or political institution, as well as vice versa. Further, despite my view that the economic institution is the most flexible, the relative importance for change of any one institution in a society is an empirical question that needs to be investigated for each major social change. In the specific propositions presented in the next section, four are explicitely put forth as bidirectional (propositions 16, 17, 24, and 25).

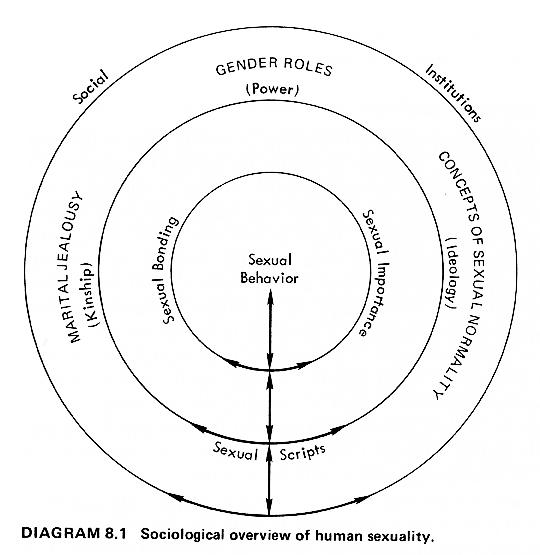

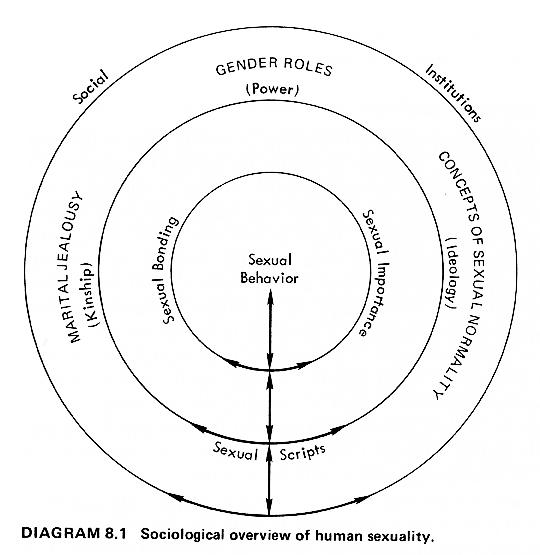

It is not possible to present a precise overview of my explanation in one diagram. However, it may be helpful for the reader to examine an abstract graphic portrayal of my overall sociological perspective in Diagram 8.1.

|

DIAGRAM 8.1 Sociological overview of human sexuality.

This diagram basically asserts that sexual behavior, due to its bonding qualities, acquires social importance and thereby becomes linked in specific ways with kinship, power, and ideology, all of which shapes our sexual scripts and is, in turn, linked to the basic social institutions in a society. As the arrows on the diagram indicate, all the causal relationships in one circle and among circles potentially flow both ways. Thus, a change in the economic or political system can affect the type of power roles given to each gender, and that may affect the sexual scripts and thereby alter sexual behaviors. This diagram is no substitute for the specific theoretical statements that follow. Still, the diagram orients one's thinking in a sociological direction. It represents the broad theoretical space into which the specific propositions will be placed in the next section of this chapter.

THE PROPOSITIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE THEORY

Now I will list particular explanatory statements (propositions) organized within the four areas that I have discussed in the preceding narrative statement of my theoretical position. The initial statements in each set are the broader "premises," or the logical bases, for other statements that follow. Accordingly, many of the statements are logically related to each other. Presenting the propositions in this more precise form, should make the theoretical structure I am building more apparent and should better serve as a basis for future theorizing and research.

Propositions on Sexual Bonding

as the Antecedent of Kinship and Gender roles

1. Societies judge stable social relationships as of great importance.

2. Societies view physical pleasure and self-disclosure as the building blocks of stable social relationships.

3. Physical pleasure and self-disclosure are the common outcomes of sexual behavior.

4. Therefore, sexual behavior will be seen as important due to its ability to promote stable relationships.

5, Such stable bonding between genetic males and females produces a context for the nurturance of offspring.

6. Stable heterosexual relationships are the rudimentary bases for husband-wife and parent-child roles; and thus, in this sense, kinship and gender roles are derivative from the bonding properties of sexual relationships.

7. Important social relationships are culturally defined in ways that are intended to institutionalize protective mechanisms.

8. Therefore, marital sexuality will involve jealousy norms concerning the ways, if any, to negotiate extramarital sexual access without disturbing the existing marriage relationship.

The presentation of these eight propositions in statement form should help the reader grasp the logical interrelations that exist among these propositions. Some of the propositions are clearly derivative from the proposition or propositions immediately preceeding them, and for those I have inserted the word therefore in the statement of the proposition. Consider proposition 4: The first three propositions imply proposition 4. Propositions 1 and 2 assert that stable social relationships are valued and that physical pleasure and self-disclosure are two important ways to promote such stability. Statement 3 then affirms that sexual behavior leads to physical pleasure and self-disclosure, which we have already asserted promotes stable relationships. It then follows that sexual behavior will be viewed as important because of its potential role in the maintenance of long-term relationships.

Reflect upon proposition 8. It logically follows from proposition 7. If the importance of a relationship determines the protection it receives, then it follows that since marital sexuality is everywhere highly valued, it will receive protection in the form of jealousy customs. In cultures where marital sexuality is most highly valued, that protection will be at its apogee, but it will be present in considerable amount in all cultures. Proposition 8 is a specific application of the more general assertion made in proposition 7.

Propositions on Sexuality

and the Power of Each Gender

9. The authorized power of a group is basically utilized to obtain valued social goals.

10. Therefore, since sexuality is a valued social goal, as a group gains power there will be increased sexual privileges in that group's sexual scripts, its erotica, and its ability to avoid sexual abuse.

11. A group's overall prestige in a society is in good part derived from its power in the major social institutions.

12. Common residence of a group increases the feelings of solidarity and, relatedly, the power of that group.

13. Therefore, the gender whose descent group reside together will achieve more power than other genders and its members will experience less sexual abuse.

14. The greater the use of specialists in the major social institutions, the greater the difficulty in participating fully in more than one institution.

15. Thus, the greater tie of the female to the nurturance of the newborn, the greater the limits on her participation in nonfamily institutions and the lower her social power in those institutions vis-à-vis males.4

Once again the propositions beginning with the word therefore (10, 13, and 15) are special cases of the more general proposition that precedes them. In proposition 15 we have an example of how institutional specialization in the family lowers the power that type of person is likely to have in other institutions. Thus, proposition 15 is a specific instance of what the more general proposition 14 states. Scientific explanation expands by means of just such logically derivative propositions as propositions 10, 13, and 15. If empirical testing shows that a logically deduced proposition such as proposition 10, 13, or 15 is empirically supported, then one has more confidence in the general propositions from which they were derived.

Propositions on Ideology and Sexuality

16. Ideologies reflect and reinforce the social values operative in each of the major institutions.

17. Therefore, to the extent that a gender's dominance is structured into the operant values of the basic institutions, ideologies will support the greater power of that gender and assign it greater rights in those institutional areas.

18. General ideologies of a culture will be productive of specific sexual ideologies that reflect compatible ideological assumptions.

19. Therefore, in a culture where one gender is dominant in the general ideology, that gender will be granted greater sexual privileges incorporated in that culture's sexual ideology and in the sexual scripts and erotica preferences of each gender.

20. Homosexual and heterosexual behaviors will each be accepted to the degree that the society defines them as integrative with the basic gender characteristics in the accepted ideologies.

21. The more rigid and narrow the gender ideology, the greater the nonconformity to the sexual aspects of such a gender role.

One value of specifically stating these propositions, is that we can discern more precisely what variables one needs to measure and what the specific nature of the proposed relationship is like (positive or negative; one-way or two-way). Ultimately, such explicit propositions make it possible to interrelate propositions that have the same variable in common or are logically related in other ways.

Propositions on Social Change and Sexuality

22. That institution that stresses flexibility the most will be the most likely to initiate change in other basic institutions.

23. Therefore, since the economic institution is the most flexible, economic changes will be a key catalyst for changes in society.

24. Changes in economic or other nonkinship institutions have a feedback (two-way)

causal relationship with changes in marital jealousy,gender roles and sexual

ideologies.

25. Changes in marital jealousy, gender roles, and sexual ideologies have a feedback causal relation with changes in sexual behavior.5

Each of these 25 propositions can be presented in terms of individual diagrams. I have composed a first approximation of such diagrams for those who are interested and placed them in Appendix B. For the general reader, the diagramatic representation of each proposition is not needed and therefore is not covered here.

THE PROPOSITIONS:

THEIR UNITY AND DERIVATION

Although far from fully spelled out there are logical interrelationships that tie together all four sets of propositions.6 In one sentence: The importance of sexuality in human relationships is the basis for the boundaries placed upon sexuality and for those in power seeking sexual rights that become part of the ideologies and the elements in any social change in sexual customs. Thus, there is a comprehensive logical and empirical unity to these propositions. It will take much additional theorizing and research to clear away more of the conceptual underbrush and define more precisely the various interstices. Nevertheless, I will make a start in that process here.

Each of the four theoretical areas starts with broad general propositions. I have noted that those propositions are the premise or the logical starting point for some other propositions in that set which relate more specifically to sexuality.7 In this fashion I hope to afford the reader a more coherent grasp of how the specific propositions on sexuality fit into the context of other, more general sociological propositions.

Many of the propositions were inductively arrived at after the reading and research I did for this book. Others were deduced from more general propositions. I could have logically elaborated these propositions, stated them more formally, and thereby created a much larger number of them.8 But they are sufficient in number and in formality for my purposes of establishing the foundation of a basic sociological explanation of human sexuality. Nevertheless, the reader should be aware that there are other propositions that can be deduced from these and that other sociological propositions exist with which these 25 propositions can be interrelated (7a).

One value of presenting my theoretical position in the format of logically interrelated sets of testable propositions is that it delineates the structure of the explanation being proposed and makes testing and elaboration that much easier. Each proposition is offered with the ceteris paribus qualification, that is, the assumption is that all else is equal. Thus, equally powerful groups should have equal access to sexuality (proposition 10) but if one of the powerful groups consists of monks who have taken an oath of chastity they will not fit that proposition so well. In such a case, all else is clearly not equal.

There are interrelationships of the propositions across the four separate sets that the reader can logically derive. Proposition 10, for example, asserts that group power relates to the sexual rights of that group. If so then group power ought to relate to the protective jealousy customs discussed in propositon 8. Additionally, proposition 10 is logically related to proposition 4. This is so because it is the importance of sexuality that makes those in power seek sexual rights. Propositions 17 and 11 both concern the influence of a group in the basic institutions and thus are interrelated through that common focus. These are but a few of the points at which the propositions in any one set logically and empirically relate to those in the other three sets. I leave it to others to tease out further the possible interrelationship among these four sets of propositions. This is one direction for future theoretical work to pursue and thereby extend and elaborate the web of propositions in this sociological explanation.9

These 25 propositions comprise the basic logical and propositional structure of my theory. Nevertheless, they are not all inclusive of the ideas put forth in this book. I have sought to minimize complexity and have left out some specific explanatory ideas that do not easily relate to these sets of propositions. Other propositions are logically implied by these propositions but they are not explicitly stated. To illustrate, proposition 10 asserts that the powerful will have less sexual restraints. From this general statement we can deduce that if anyone is going to be restricted from body centered sexuality it will be the less powerful. Since women are generally less powerful than men, we can further conclude that they will be more restricted from such body centered sexuality. Note that this deduction is in accord with tenet 2 of the nonequalitarian sexual ideology.

In the five causal diagrams in this book I have presented some specific empirical tests based upon analysis of the Standard Sample which are relevant to several of these propositions.10 A good number of the 25 propositions stated in this chapter were partially derived from an examination of those causal diagrams. Rather than burden the reader here with the detailed derivations I include my comments about them in the Selected References and Comments section at the end of this chapter.11

I will mention here that I did not take each concrete two variable correlation in the causal diagrams and make it into one of my propositions. Instead I sought to make the propositions somewhat more abstract and general and more easily related to general sociological propositions. There is a clear theoretical advantage to a proposition having greater scope of applicability. But my major reason for being more abstract was that I wanted the propositions to represent those more general relationships which I had logically derived after contemplating the theoretical implications of the findings in each diagram. I felt that was preferable to simply accepting every specific correlation between two concrete variables as a separate proposition. Given the limitations of the available data, it seemed wiser not to just literally accept all correlations in every diagram at face value.

Finally, I should add that the propositions are far from being simply based on the five causal diagrams. They derive largely from general sociological theory, from other cited sources on industrial and nonindustrial societies, from logical fit with a prior theoretical position, and from my general theoretical intuition. There surely is a personal, almost esthetic aspect to any theory. Fortunately, this is all subject to future testing, verification and alteration by myself as well as others.

There is always the possibility of someone developing a different theoretical explanation that more parsimoniously explains the same reasoning and empirical findings using different propositions than mine. Science is the tentative possession of partial truths. When you are certain you have the final explanation you have departed from the scientific realm. I encourage others to present their alternative or additional propositions. 12

Some specific concepts beg for elaboration. Propositions 9 to 15 all deal with power, and some of the ideology propositions (17 and 19) also relate to power. Surely, then, there is a pressing need for a more developed theory of social power than that presented in this book. Power was a major causal variable in many of my explanations. A more formalized theory of social power would allow for more precise formulation and testing of the many propositions relating power to sexuality. The concept of normality is another crucial area begging for further clarification. I have commented upon the need for other conceptual clarifications elsewhere in this book. Our theories are only as clear as our concepts, and therefore conceptual clarification is a most strategic area for future work.

I believe that my propositions specify the major sources of the societal determinants of our sexual customs. In addition to simply pointing to kinship, power, and ideology as universal linkages, we have traveled some distance in showing how specific segments of these linkages interrelate with each other. More than that, this sociological theory allows us to explain variation in the ways these universal linkages operate in different societies and to account for changes in them. That is, we can state the conditions under which jealousy will be stronger (proposition 7 and 8 and others) or female power stronger (propositions 13 to 17 and others). Accordingly, we can predict what specific alterations in a society would affect sexual lifestyle outcomes. If you carefully read over these propositions, you will become more aware of their potential for explaining variation in sexual customs in present societies.

I have mentioned that the Standard Sample is but one source of these propositions. A great deal of other data and ethnographic accounts were consulted, and modern industrial societies were examined as well as other types. I do believe that these 25 propositions apply to all types of societies and to a variety of sexual areas. To illustrate, they can be used to analyze premarital sexuality in America. Does proposition 7, concerning protective mechanisms, apply to premarital sexual relationships? Surely premarital sexuality has jealousy-provoking situations - particularly in important stable sexual relationships. It would be necessary to specify more precisely the conditions that maximize such an outcome, but the proposition does seem generally applicable. Likewise, the propositions on power and gender (propositions 9 to 15) could be checked to see if our premarital sexual customs also reflect gender power differentials. I suspect that there is generally less of a gender gap in power in the premarital period than in the marital period. We could develop specific propositions to explain this.

We know that unmarried people share the tenets of our sexual ideologies (see Chapter 5), and so we assume that our general ideology influences our sexual ideology as asserted in proposition 18. The specific differences in sexual standards premaritally as compared to extramaritally could be explored. Finally, the role of economic factors in the rapid changes in premarital sexuality in the 1965-1975 decade can be explored to see if it is compatible with propositions 22 to 25. Does, for example, the increased ability of women to earn income contribute to their greater interpersonal power in ways compatible with propositions 15 and 24? Overall, my judgment is that the evidence would support the explanatory power of these propositions for premarital sexuality in America and would lead us toward the development of additional and more specific propositions. Specification and elaborations of precisely this sort are what is needed to develop further the social applicability for this explanation of sexuality.13

Clearly, there are many loose theoretical threads that demand further examination. My goal is, not closure of the theoretical search for a societal-level explanation, but the opening up of this exciting endeavor. I present you here with a rough map that contains some of the explanatory keys related to human sexuality. I hope this will lure many of you to set forth and refine this map and further unearth the treasure that lies within.

CODA

This has been a five-year journey for me - one of the most complex I have ever taken in my academic career. By the same token, it has been one of the most satisfying. In a sense, the denser the jungle, the greater the pleasure in finding your way out. When I started on this project I surely could not have predicted the theoretical form this book has taken. The joy I am now experiencing comes from the knowledge that I was able to progress toward the goal of understanding how human sexuality is knit into the social fabric. 14

I have made it clear that in terms of developing a scientific explanation of human sexuality, each science is at its best when it, to paraphrase Voltaire, tends to its own garden.15 All sciences have had generations in which to develop their methodology, their particular theoretical explanations, their techniques of analysis, and their central explanatory concepts. If one tries to combine theoretically all the major scientific disciplines that study sexuality, then each area loses some of this knowledge and expertise that has been developed over many years. I know of no individual who can keep up with everything in even one of these disciplines, let alone in all of them. What we often end up with in multidisciplinary scientific theorizing is a watering down of all the fields that are combined.16

On the other hand, I am not proposing that other fields have no value for a sociological or societal-level explanation of sexuality. I certainly have used knowledge from psychology and biology in this book. But I have used knowledge from these fields only when it has thrown additional light on the development of a distinctive sociological explanation, Most importantly, the major sexual differences that appear across cultures and within one culture across time evidence that there is a great deal that requires a special societal-level explanation. I have focused my energy on developing just such sociological explanations.

Even so, I would not object to an attempt by others to integrate the specific scientific explanations from psychology and biology with my sociological approach. However, I would also not hold out much hope for a successful outcome because at this stage in our scientific understanding of human sexuality each science has too little to offer toward such an integrated perspective. Perhaps when each of the various sciences concerned with sexuality has a deeper understanding of human sexuality, we may more profitably combine our explanatory schemas. The sociological explanation is the newest and is therefore the most in need of domestic nurturance before it seeks to mate with other explanatory schemas. Even then, I am not at all convinced that viable "offspring" will be possible from such unions.

Despite my emphasis on specialization for those doing research and theory work I particularly do not want to discourage the use of materials from other disciplines by those in applied professional fields in education, social work, and therapy. I think that therapists dealing with sexual problems can learn much about the possible place that kinship, power, and ideology may have in the problems their patients or clients present to them. Having a broad cross-cultural approach can be very useful to a therapist - as I have noted in my discussion of normality in Chapter Five. In addition, the therapist or sex educator will benefit by knowing the research and theory coming out of biology and psychology. Therapists can find much in such knowledge that will inform their work with clients and patients.

Nevertheless, in applied fields like therapy, as in the basic sciences, I do not think this knowledge will be the building stones of a theory of effective therapy. A theory concerning therapy must be built on the expertise of the professionals in that field. Other fields are helpful in interpreting some of the problems brought by patients and in suggesting which therapeutic techniques will work best. That is undoubtedly of considerable value. It is still the case however, that the essential ingredients of a therapeutic approach are built predominantly upon the expertise of the therapist qua therapist. Therefore, although I would strongly encourage the seeking of multidisciplinary knowledge by practitioners, I would encourage a search for an integrated multidisciplinary explanation of sexual therapy. A theory about sexual therapy explains therapy and not sexuality.

As I mentioned in the opening chapters, science does not seek to define nor explain total reality. Philosophy deals with such imponderables. Each science specializes both in the substance of interest and in the level of analysis utilized. As further evidence of the value of such a specialized approach, I would point out that it has been just such single disciplinary work that comprises the bulk of the research and theory contribution made in this century to the study of human sexuality.17

Given my focus upon sociology, one may justifiably ask why I have relied so heavily on anthropological studies. Cultural anthropology is a social science discipline very similar to sociology. The basic difference is that anthropology focuses more on a cross-cultural approach and is somewhat less demanding in terms of quantitative methods. Of first importance is that the level of analysis and the concepts utilized are very much alike in both disciplines. In my thinking, when that occurs, from a theoretical perspective, you have but a single discipline. In fact my approach in this book is often called comparative sociology which is indeed very difficult to distinguish from cultural anthropology. The focus upon the societal level of explanation in both comparative sociology and cultural anthropology is strikingly similar. For that reason I consider sociology and cultural anthropology sibling disciplines. In many universities they are still in one unified department.18

Much is still left unsaid here and, in some instances, unexplored. There are many areas of sexuality upon which I have touched only lightly. I have focused upon those areas of sexuality that have at least a modicum of cross-cultural research in the published literature and are relevant to a societal-level explanation. My first goal was to find the societal linkages to sexuality that would apply to all societies, and thus I had to follow where this objective led me. My objective in this book was a societal-level theoretical explanation of sexuality and not an encyclopedic coverage of all key sexual topics.

My explanations will, I hope, be a start toward an understanding of even those areas of sexuality that I have not directly explored. The advantage of formulating a cross-culturally valid broad explanation of sexuality is that logically such an explanation should have implications even for those areas of sexuality not fully examined. Also, if the theory is weak in any direction, future research on such areas can point the weakness out and new theoretical elements can remedy that problem.

My wish is that having made the effort to organize the key societal linkages and their theoretical ties to the patterns of human sexuality, I will have provoked enough interest to encourage more people to join the development of this sociology of human sexuality. The causal search is neverending, for causal solutions are always tentative.19 The primal scientific instinct is to challenge, not to accept. It must always be that way if we are to find reliable and valid answers to our quest.

Theoretical space is free to all. So come and examine, reason about, question, and qualify what I have done, I do hope that what I have said is of value to all who work in the area of human sexuality in whatever capacity. There is also relevance to those who have a personal, but not a professional, interest in understanding sexuality. My propositions can be elaborated so as to afford usable and relevant knowledge for many commonly raised questions. For one thing, you should now be more aware of alternative sexual systems and know something more about the costs and rewards of each in terms of your own set of values. This breadth of knowledge should afford you a deeper understanding of the social basis of the many disputes in out society concerning sexual jealousy, erotica, homosexuality, gender power, and sexual normality. The explanation of something as important as human sexuality must be complex, but the operation of theory is to simplify and thereby point to the patterns that exist in what William James called that "booming, buzzing, confusion" labeled reality.

I have one final suggestion. It would be far more helpful to the improvement of our scientific understanding if we minimize politicizing the scientific investigation of sexuality. There is a place for pleading our special moral concerns, and it is in our many private roles as citizens. I believe that we need also to respect the importance of the attempt to do impartial, fair, scientific analysis. I am sure that such scientific knowledge and understanding can aid us in our applied and political goals as well as in purely scientific ways. With this in mind, we may well find it profitable to allow this new sociological perspective an opportunity to demonstrate its potential in our lives.

There are those who will say that my findings verify much of the Marxist position or of the feminist positions that have recently been taken. Some may even think I have also found support for aspects of Freudian or sociobiological approaches. As I see it, my theory and my empirical data in their general outline and in their specifics do not comfortably fit with more than pieces of any of these older approaches.

Of course, some overlaps do exist - some rather striking ones such as the importance of social power in structuring sexual customs - but there is one rather important distinction to bear in mind: I have no allegiances to the dogmas of any other position as to how power or other social factors operate. I have strong loyalty to a sociological, societal-level explanation. That is my only dogma. Lacking allegiances to these older approaches, my explanation is freer to take the wisdom of all these approaches and thereby enhance the societal explanation of human sexuality.

I thank you all for your coming along with me on this exploratory voyage. I hope it will be but one of many voyages for you into the fascinating puzzle of human sexuality. Perhaps you will be able to advance us further into the labyrinth that contains the means of deciphering our human sexuality. I wish us all the best of good fortune in the future development of this sociological enterprise. We have nothing to lose but our preconceptions and we have a new understanding to gain.

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

1. There are other reasons for incest taboos, such as the potential abuse of the child due to the power differential with parents. This was briefly discussed in Chapter 4. Anthropologists in particular have analyzed the societal reasons for incest taboos. A perusal of the journal American Anthropologist would be a good place to start for the interested reader.

2. In America we have tied sexuality to notions of power and aggression so much that we may believe that all societies also do that. However, other Western countries do not give the same aggressive meaning to sexuality. For example, I spent the year 1975-76 in Sweden at Uppsala University and explored the way sexuality was conceptualized in Sweden. Just as one comparison, in America if you have been given a raw deal in buying something, you can say you were "fucked," which means the same as saying you were "treated badly." In Sweden the word for sexual intercourse cannot be used in that fashion. This indicates to me that sexuality itself in Sweden may be less likely to be used as a way of treating someone badly. Our conceptualization of the meaning of sexuality is reflected in our everyday usage and would reward any examination.

3. The economic institution need not always be the most flexible or important institution in a society. In this sense it would likely be wise to follow Alice Schlegel's advice and search for which institution is the most influential in a particular society. In my propositions, I do endorse the idea of ranking the influence of each of the major institutions. This would eventually lead to our being able to formulate more precise propositions. For an excellent discussion of "central" institutions and gender stratification cross-culturally, see

Schlegel, Alice, "Toward a Theory of Sexual Stratification," Chapter 1 in Alice Schlegel (ed.), Sexual Stratification: A Cross Cultural View. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977.

4. Some of Chafetz's propositions on power and gender are congruent with mine.

Chafetz, Janet. Sex and Advantage: A Comparative Macro-Structural Theory of Sex Stratification. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman & Allanheld, 1984.

5. Logically, I should also consider change caused by forces external to a particular society. For simplicity sake I have not entertained any propositions concerning that in my theory. Colonialism, war, and trade are but a few of the means by which external forces may alter a particular society.

6. I call all these theoretical statements by the term proposition, but clearly not all the statements are of the exact same sort. However, all the statements are subject to empirical testing, relate two or more variables, and are part of the logical structure of my overall theoretical position. For excellent coverage of the use of propositions in social science theory, see the following references:

Hoover, Kenneth R., The Elements of Social Scientific Thinking (3rd ed.). New York: S. Martin's Press, 1984.

Wallace, Walter L., Principles of Scientific Sociology. New York: Aldine, 1983.

Zetterberg, Hans L., On Theory and Verification in Sociology. New York: Tressler Press, 1954.

Reynolds, Paul Davidson, A Primer in Theory Construction. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1971.

Chafetz, Janet S., A Primer on the Construction and Testing of Theories in Sociology. Chicago: F.E. Peacock, 1978.

Hage, Jerald, Techniques and Problems of Theory Construction in Sociology. New York: John Wiley, 1972.

Burr, Wesley, R. Hill, 1. Nye, and I.L. Reiss," Metatheory and Diagraming Conventions," Chapter 2 in W. Burr, R. Hill, 1. Nye, and I.L. Reiss (eds.), Contemporary Theories about the Family. Vol. 1, New York: Free Press, 1979.

Freese, Lee (ed.), Theoretical Methods in Sociology. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980.

7. The premise one starts with is logically called an axiom or postulate. In a strict sense such premises are not empirically testable. From such axioms one can deduce theorems that are themselves testable. If the theorems are not shown to be false, then we have more faith in the premises of our thinking. Clearly, we are far from any complete axiomatic theory. Also, theory can proceed in other ways. It is well, in any case, to examine empirically and logically all aspects of any theoretical position - even those called premises. Even mine!

Lee Freese's theoretical writings are particularly relevant to this point. Although he stresses axiomatic theory more than I would, his ideas are worth examining. See

Freese, Lee (ed.), Theoretical Methods in Sociology. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1980.

8. Propositions 5 and 6 concern speculative evolutionary notions. Of course, one may be skeptical about those without rejecting the propositions concerning present-day societies.

9. The concepts in each of the 25 propositions need to be able to be precisely measured, and thus careful definitions and measurement procedures are necessities. For a somewhat technical statement of conceptualization and measurement I recommend

Blalock, Hubert M., Jr., Conceptualization and Measurement in the Social Sciences. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1982.

10. For a philosophical article by a quantitative scientist on the problem of cross-cultural data, see

Campbell, Donald T., "Degrees of Freedom and the Case Study," Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 8, no. 2 (July 1975), pp. 178-193.

11. In the examination of the Standard Sample, I sought to causally explain five sexually relevant outcomes: (1) beliefs that females are inferior; (2) sexual jealousy reactions of husbands; (3) sexual jealousy reactions of wives; (4) homosexual frequency; and (5) rape proneness. I will note some of the ways in which these analyses related to the propositions discussed in this chapter. The analysis of marital sexual jealousy (Diagrams 3.1 and 3.2) brought out variables like the importance placed on property in a culture as a predictor of the degree of husband sexual jealousy. I took the emphasis on property to be a measure of male power and therefore conceived of the association of that variable with husband sexual jealousy as partial support for propositions 8 and 10. Also, the relation of male kin groups to husband sexual jealousy is congruent with proposition 13's emphasis on the importance in sexuality of kin group power.

In Diagram 4.1 I interpreted the positive relationship of a belief in female inferiority to the degree of mother involvement with infants to be supportive of propositions 14 and 15, which point out how involvement with the family lowers one's power in other institutions. This same point is supported by the negative relationship in Diagram 4.1 between male kin groups and father-infant involvement. The male kin group promotes male power and that reduces participation in childcare roles. That diagram also is consistent with proposition 16 which asserts that institutional values will be reflected in ideological beliefs. The belief in the female's basic inferiority is reflective of the female's limited power outside the family.

Proposition 24 asserts the power of the economic institution in terms of gender roles and that too is illustrated by the place of agriculture in Diagram 4.1. Note however, that proposition 24 asserts that a two way causal relationship exists. All my causal diagrams presented only one way causation. The reason for that is that two way causation is much more difficult to test for and demonstrate. The path analytic techniques are much simpler if one way causation is assumed. Nonetheless, I deliberately implied in several of my 25 propositions that causation was bidirectional. We cannot examine everything at once and the steps taken in this book are preparatory for more complex causal analysis at a later date.

My interpretation of Diagram 6.1 on homosexuality is expressed in part in proposition 21. The association in Diagram 6.1 of the extent of class stratification and of strong mother-infant involvement with the prevalence of homosexual behavior fits with the notion that rigid gender roles promote homosexual behavior especially in cultures like the U.S.

Propositions 10 and 13 are logically related to the relationships found in Diagram 7.1 concerning rape proneness, Those propositions imply that having low status and weak kin ties can increase the chances of sexual abuse. This is consistent with the association of a belief in female inferiority with rape proneness. I did not include a proposition directly on machismo and rape because it is not clear to me just how separate machismo is from other measures of male power, and propositions 10 and 13 already make the point concerning the relation of male power to rape. The lack of any clear tie of violence rates to rape rates also kept me from formulating any propositions in this area.

The causal diagrams, as can be seen in my discussion, do not answer a great many of the questions that arise in our thinking. They were but one of several sources for the propositions in this chapter.

12. A few new cross-cultural codes deserve attention. I did not feel they were essential for me to analyze at this time, but they are worth examining. See in particular

Barry, Herbert, and Alice Schlegel, "Measurements of Adolescent Sexual Behavior in the Standard Sample of Societies," Ethnology. Vol. 23, no. 4 (October 1984), pp. 315-330,

Mosher, Donald L., and Mark Sikin, "Measuring a Macho Personality Constellation," Journal of Research in Personality. Vol. 18 (1984), pp. 150-163.

Frayser, Suzanne G., Varieties of Sexual Experience. New Haven, Conn.: HRAF Press, 1985.

13. Some readers of this book may be familiar with my earlier theoretical work and may wonder how that ties in with this book. I commented upon this in note 6 in Chapter One and note 48 in Chapter Four in my 1967 book. I had developed a theoretical explanation of premarital sexuality that I called the autonomy theory. This theory, in its briefest form, asserted that "the degree of acceptable premarital sexual permissiveness in a courtship group varies directly with the degree of autonomy of the courtship group and with the degree of acceptable premarital sexual permissiveness in the social and cultural setting outside the group" (Reiss, 1967: p. 167). Two key causes of premarital sexuality are identified in that statement: the social and cultural setting and the autonomy of the courtship group.

My current theoretical effort spells out the factors that affect "the degree of acceptable sexual permissiveness in the social and cultural setting." In this sense, this book is an extension, on a much broader scale, of my earlier work. What of the autonomy notion itself, though? As I noted in Chapter Four, note 48, autonomy of a group is in a sense a measure of its power. A courtship group that is boxed in by parental regulations, religious edicts, political laws, and lack of money is low on autonomy and low on power. To be autonomous a group needs to be freed from such influences, and that means a reduction of the ability of these external groups to affect the lifestyle of the courtship group. Since the power dimension has shown itself to be such a major influence in my current work, this earlier statement of autonomy may be able to be integrated with a fuller analysis of the role of power in sexuality. I hope others will help me to explore my autonomy theory and seek further to integrate it with my current theory. For now, I merely want to let the reader know that the idea is not forgotten nor is it alien to my current theorizing.

I have also done theoretical work on extramarital sexuality. I did utilize measures of the major social institutions in that explanation. The sociological theory in this book is a global sociological explanation. As such it should be inclusive of my theoretically narrower explanations of both premarital and extramarital sexuality. I do plan at a later date to deal with these interrelationships. Some key references to this earlier work follow:

Reiss, Ira L., The Social Context of Premarital Sexual Permissiveness. New York: Rinehart &Winston, 1967.

Reiss, Ira L., and Brent C. Miller, "Heterosexual Permissiveness: A Theoretical Analysis," Chapter 4 in W. Burr, R. Hill, 1. Nye, and I.L. Reiss (eds.), Contemporary Theories about the Family (vol. 1). New York: Free Press, 1979.

Reiss, Ira L., Ronald E. Anderson, and G.C. Sponaugle, "A Multivariate Model of the Determinants of Extramarital Sexual Permissiveness," Journal of Marriage and the Family, vol. 42 (May 1980), pp. 395-411.

14. The difference between a sociological-level explanation and a psychological-level explanation can be seen in some of Broude's work. In an examination of the double standard in extramarital sexuality, Broude concludes that the double standard is interpreted as a reflection of both male fears of sexual betrayal and male concern over sexual adequacy. (Broude, 1980; p. 181)

This is a psychological-level explanation stressing individual fears of adequacy. It is not necessarily in conflict with a sociological-level explanation, but it clearly is different. In contrast with Broude, I interpret the double standard in extramarital sexuality as a reflection of a social structure that places males in the top power positions in most societal institutions.

Broude, Gwen J., "Extramarital Sex Norms in Cross-cultural Perspective," Behavior Science Research, vol. 15, no. 3 (1980), pp. 181-218.

15. Voltaire, Candide and other Writings. New York: Random House, 1956. (See especially p. 189.)

16. I have developed my thinking on this topic in the following article:

Reiss, Ira L., "Trouble in Paradise; The Current Status of Sexual Science," The Journal of Sex Research. Vol. 18, no. 2 (May 1982), pp. 97-113. (See the May 1983 issue of this journal for a response to my paper and my rebuttal.)

17. For a discussion of this point see the article cited in note 16. To obtain a general view of the study of sexuality 25 years ago see:

Ellis Albert and Albert Abarbanel (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Sexual Behavior (2 vols.). New York: Hawthorn, 1961.

18. Anthropology has specialities that are unique to it, for example, physical anthropology and archeology. Sociology also has special approaches, such as the micro approach. The micro approach focuses upon human interaction in small groups. Some of that was used in this book, particularly in our discussion of jealousy and erotica and sexual scripts. However, my overall unit of analysis was the society or the major institutions in a society. That is called a macro or comparative approach. Other sociologists may identify as Marxists or phenomenologists, and that further distinguishes them. In sum, then, when I say sociology and anthropology are alike in their level of analysis I am speaking of cultural anthropology and macro comparative sociology.

A micro sociological approach is one that also can be further explored. Such an approach would focus upon socialization and the interactive processes by which people learn their sexual scripts. Such a micro sociological approach could be theoretically linked with the macro theory I am developing. The work of Simon and Gagnon cited in the Bibliography is relevant here.

19. It was David Hume who, over 200 years ago, made science aware of the tentativeness of its causal assertions. In sociology it was Robert MacIver who was one of the first sociologists to examine carefully the notion of social causation. See

Hume, David, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. LaSalle, Ill.: Open Court, 1952. (Originally published in 1777.)

MacIver, Robert M., Social Causation. New York: Ginn, 1942.

|