|

THE POWER FILTERS

GenderRoles

THE SOCIAL NATURE OF GENDER

POWER AND GENDER

A TEST OF A THEORY OF GENDER INEQUALITY

THE LINKAGES OF POWER, KINSHIP, AND GENDER

POWER AND SEXUALITY

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

THE SOCIAL NATURE OF GENDER

There are those who feel that what men and women do in a society is what is "natural" for them in accord with their biological makeup. Thus, women care for children because, by their nature, they bear them and enjoy nurturing them; men tend to warfare because they are, by their nature, aggressive. This perspective is similar to what we encountered in our discussion of sexuality in Chapter 2. We noted there that many people felt sexuality was just "doing what comes naturally" and was explainable by its tie to reproduction. The reader is aware that we rejected much of that position. Here, analogously, I will qualify biological determinism by evidencing the societal impact on gender roles. Even though most of you may reject such determinism, it is well to spell out the boundary limitations of a biological and a sociological explanation of gender.

To be sure, female wombs and male hormones cannot be denied. What can be disclaimed is that they explain the bulk of gender-role behavior. Surely, biological explanations are almost totally inadequate when our questions concern differences in gender roles among cultures, for if a common genetic base accounts for male-female differences in gender roles, then that similar base cannot account for differences among cultures. If that common genetic base was the full explanation, there would be zero variation in gender roles around the world. I certainly do not deny that biology has some influence on gender roles, but biology is not helpful in explaining why gender roles are not the same in various societies.

One other qualification of the common biological deterministic view of gender roles needs to be put forth. There is no necessity that females take the lion's share of childrearing just because they have a womb in which that child was created. Societies do modify the role of mothers in accord with pressures from the economic system and elsewhere. If female labor is needed outside the family role, then males, children, and the elders will share in childrearing so as to free women for outside work. We can see this in some matrilineal societies where women work together and play the important economic roles. In such a setting the woman's brothers and her mother and older children will make it possible for the woman to work cooperatively with other women, and people will not expect mothers to be the predominant source of childcare.

In the Standard Sample, 8% of the cultures have other people who do more than mothers in caring for infants, and another 39% have others who have important roles in infant caretaking.1 In the remaining 53% of the societies the mother is the predominant caretaker of the infant, while others have very minor roles. Low involvement in infant care is much more common for fathers; in 23% of the societies fathers have almost no caretaking roles with infants, and in 47% they have only occasional roles. In only 30% of the cultures do fathers have frequent or regular companionship with their infants.

This still means that there are societies where childrearing is considered equally a father's and a mother's task. Margaret Mead described the Manus society off the coast of New Guinea as one such society. Males are considered more nurturant than females, and Mead reported that when she introduced dolls to the people, it was the boys, not the girls, who treated the dolls like babies. 2

Thus, while a clear cross-cultural male-female difference in care of infants is evident, it is equally apparent that there is considerable variation in the role of mothers and fathers in infant care. Much of this variation is due to societal pressures and norms that affect the relative involvement of mothers and fathers in infant care. Surely the fact that the mother has carried the child during pregnancy is a powerful force toward future infant care, but societal pressures always organize the ways in which that care will be carried out. So, culture has the power to program any biological capacities that we may possess. In fact, since we are all raised within some type of social structure, we will never really experience our "biological nature" in any pure sense.

The importance of knowing more about societal sculpturing of biological differences between males and females lies in the implications of this knowledge for social change. If biology were fully determinant of gender roles, then little could be done to alter them. But if biology only establishes tendencies and if society always organizes and structures these tendencies, then regardless of what biological differences there are between men and women, we can, through our socialization process, achieve the types of gender roles we desire.

True, it may be difficult to alter dramatically the female tie to infants because females carry the fetus during pregnancy and because hormones like oxytocin reinforce the female-infant tie. The cry of the infant releases oxytocin in the mother, which aids in the flow of her breast milk .3 Such outcomes may well encourage mothers to nurse infants; but before you are seduced by biological determinism, think about the fact that most American women do not nurse their infants although they have oxytocin in their bloodstreams. Clearly, then, the shaping of these flexible biological tendencies by societal demands is possible and inevitable. It may well be wise to be aware of what biological tendencies exist so that we know what dispositions we are working with in human societies. It would be foolish, however, not to realize the plasticity of these biological propensities. I believe that most biologists today would agree with this point.

Looking at the genetic male for possible biological determinants of his gender role, I would agree with Maccoby and Jacklin's conclusions concerning the higher levels of aggressiveness in males that prevail in almost all primates.4 Evidence from human and nonhuman primates indicates that male aggressiveness is likely tied in some ways to the presence in males of much higher levels of the androgen hormone. Evidence suggests that among other male primates physical combat increases androgen levels in the victor and decreases them in the vanquished. Administration of androgen to male primates, especially dominant males, does increase their levels of aggressivity.5 Finally, in virtually all cultures the act of warfare or of organized killing is done by males. Without belaboring the point, it seems that males have a biological tendency for higher physical aggression than do females. Maccoby and Jacklin define such physical aggression, as most scientists do, as an attempt to hurt someone.

That the average male may be more aggressive than the average female may mislead the reader into ignoring the considerable overlap between the sexes. It is likely that a large proportion of males and a large proportion of females are very similar in aggressive potential, but the remaining proportion of males move toward the higher levels and the remaining group of females move toward the lower levels of aggression. Thus, the averages do come out significantly different. This point is important to grasp, for it makes it easier to appreciate that if large proportions of males and females are already similar on aggression, then male-female differences can certainly be muted by social training.

To illustrate the role of learning in aggressiveness, one need only note that in our society males and females under five years of age are quite different in physical aggression despite the fact that at that early age they are rather similar in androgen levels. It is after age nine or ten that the large male-female differences in androgen appear.

Apparently, then, social factors train very young male and female children into their gender roles without much support from androgen levels. The ease of modification can be seen by comparing violent-crime rates in different Western societies. We are the leader in this measure, but I doubt if our males have any more androgen than the Scandinavian males who have relatively low rates of violent crime.

If you accept my position - that although there are biological differences between males and females, such tendencies are molded and modified by societal conditions - then it follows that we can alter gender roles in accord with our values if we are willing to put forth the effort required. Relatedly, if we grant this flexible view of biological tendencies, it then becomes pointless to argue over the reality of male-female biological differences.

Such arguments over how much is biologically determined are often undertaken in order to support one's ideological position regarding gender-role equality. Accordingly, those who reject gender-role equality seek to establish male dominance by stressing biological differences, while those who defend gender-role equality seek to establish the validity of their views by denying male-female differences. Once we grant that whatever biological tendencies exist are constantly being socially modified, then we need no longer debate such issues.

Aggression hardly establishes dominance by itself. One needs social skills and group alliances to obtain political power, and aggression alone is insufficient. Were it otherwise, professional football players would be our leaders, for they are probably very high on physical aggression. We have had more professional movie actors in Washington than professional football players. This should tell us something about what it takes to gain power.

My conception also implies that having more oxytocin or possessing a womb does not guarantee devotion to infant care. Those women with the highest oxytocin levels are not necessarily the leaders in childcare, for that form of leadership also takes social skills and knowledge of how to nurture children for the specific type of society in which they must live. Furthermore, we have seen that in almost half the societies there are other important nurturers of infants besides the mother, and in three out of ten societies, fathers are heavily involved in infant care. Once more the flexibility of our biological inheritance is demonstrated. There are biological tendencies, but they are demonstrably malleable if we are willing to pay the cost of shaping them in the directions we prefer.

In sum, since we are all born into existing social systems, biological tendencies will be unable to express themselves without being shaped by the social environment. Most biologists today would accept this position even if they do focus upon the biological tendencies and not the societal sculpturing of these potentials. Biologists know now that the hypothalamus affects the pituitary gland and through it the workings of the endocrine system, which regulate our hormonal syntheses. The hypothalamus is part of the brain and as such is affected by our brain processes. Thus, biological research itself has revealed that our societal training, which also affects our brain processes, has a direct pathway toward shaping the biological potentials of our bodies.

The relationship between the biological and social is clearly an interactive process. But having said that does not specify the precise ways in which each factor operates nor how both factors interact. Some scientists may choose to deal with the interactive process and specify how these two types of causes affect each other. I prefer to specialize on the power of the societal. This does not deny the importance of biological potentials or tendencies; rather, it takes biology as a constant and then looks to explain the variation in male-female roles by examining the variety of societal systems involved in shaping such roles.

One final little-known illustration should convince the reader that societal gender roles have a high degree of freedom from biological determination. Although this sounds impossible to many Westerners, there are cultures that have more than two genders.6 One of the best-known examples occurs among the Navajo Indians in North America. They have a third gender known as the nadle. The entry into this gender is by two pathways: (1) if an infant is born with ambiguous genitalia that makes it difficult to know if the child is a male or female and (b) if a person feels very unhappy in the male or female gender role and wishes to change to another gender. The nadle gender can combine the rights and duties of the male and female genders with the exception that they cannot hunt and cannot participate in warfare. They may marry and dress in any way they wish and perform a wide variety of tasks.

Other societies recognize more than two genders; some, four or five. Usually the reasons given are the same as with the Navajo: either the presence of ambiguous genitalia at birth or the unhappiness of being assigned to the male of female gender. Although such instances are not common, their very presence supports the separation of biology and gender. Clearly, genetic makeup of individuals, though obviously important, is only partially the basis for being classified into a gender. Each society not only shapes the content of a gender but, in some cases, also decides how many genders will exist.7 Thus, one may conclude that while there are obvious conjunctures of biology and gender, there are equally obvious disjunctures, and the role of culture in structuring gender looms large in any explanation.

POWER AND GENDER

It is the seemingly universal difference in societal power of the genders that sparks one's intellectual curiosity to ask why. As I have discussed, the biological determinist's answer is unsatisfactory and incomplete. Even if we were to examine only one society, we know that the power differentials of the genders may vary in each generation whereas biological differences between males and females changes only over the cons. We therefore must search for societal-level explanations whether we deal with one or a thousand societies.

First, let us define power as the ability to influence others and achieve one's objectives despite the opposition of the other person.8 Thus, power is a measure of interpersonal influence. I mention the opposition of the other person, for it is not a test of power to persuade someone who is indifferent on the issue or who already agrees. It is a test of power when someone puts up resistance, for then we have a measure of the force one can exert.

In society there are two basic types of power. The first we can call authorized or legitimate power, and it is based upon the norms of a group or society. Such legitimate power is thus authorized by the role one plays or the social position one occupies. A teacher, for example, has an element of legitimate, normatively assigned power over the students in his or her class. Also, in many traditional Western countries, a husband still has authorized or legitimate power over his wife, as the phrase "to honor and obey" implies. A second type of power is unauthorized power, which is a measure of the degree of influence one person has over another that goes beyond what the norms dictate. Thus, a student who persuades a professor to change a grade because he or she is the son or daughter of a close friend, has unauthorized power. Likewise, if a wife in a traditional Western society dominated her husband, that would be a sign of her power, but it would be normatively unauthorized power.

Sociologists generally agree that the positions a group holds in the basic institutions in a society are the key sources of what power any group possesses. These basic institutions are familial, political, economic, and religious.9 To understand the level of authorized power of males, females, or any group, one needs to examine authorized and unauthorized influence of that group in these major institutions. Consider for a moment the place of the female gender in American society in terms of our basic institutions.

In the family institution the female, even today, is viewed as the homemaker.10 Traditionally, the male who is her husband has been assigned authority over her. This is changing, but even at present a husband who has the predominant share of influence in a marriage raises fewer eyebrows than does a wife who has the predominant share of power in a marriage. Although equalitarian marriages have become acceptable in America, female-dominant marriages are still far from widely accepted. This perspective points out just how much and how little has changed.

Examine the political institution. Women in America occupy about 10% of the elective offices in the country. They control only about 4% of the seats in Congress, though they represent over 50% of the population of the country. The percentage of women in political office increases as the prestige of the position decreases.11 There is today one female governor but quite a few female mayors. It is not difficult to discern the lack of female political power in our society, and this is rather typical for a Western society.

In the economic institution, full-time employed women earn about 60% of what full-time employed men earn. Further, about half the employed women work part time, whereas only about 20% of the men employed work part time. Small segments of women in the professions such as law, medicine, and dentistry have made economic gains, but about 75% of women are still employed in jobs stereotyped as women's work and ranked low in the prestige values of our culture.

How many women are rabbis, priests, or ministers? Some religions like the Catholic Church, many Protestant sects, and Orthodox Judaism forbid women to occupy the leadership role men have held for centuries. Even in those religions that have recently accepted the presence of a female religious leader, very few women are in the pulpit.

Finally, in education we still find female college students electing those fields that pay the least in future jobs. More women elect majors in home economics, the humanities, and primary school teaching than do men. Even in Scadinavia, one of the most gender-equal of the Western countries, we find a similar difference in choice of fields in the universities, although not as one-sided as in America. In fact, an overview of Scandinavia reveals that although we would find more gender equality in all the major institutions, it is obvious that the Scandinavian countries have not achieved anything near full gender equality in any of these institutional areas.12

The place of women in these basic institutions in the West is not a mere chance occurrence. The traditional definition of the female gender role promotes precisely such an unequal integration of women in the societal institutional structure. Even at the present time, many Americans probably expect a woman to give priority to her family and not to pursue a career with the vigor that a male does. That expectation is part of the consensual gender role of women, and it acts as a block to any change in gender power. When women's priority is in the home, women will have a most difficult time achieving equality outside that home. The inequality in outside roles will inhibit equality even in the home. The woman may gain some unauthorized power by her special talents or by her behind-the-scenes maneuvers, but the very dependence upon such unauthorized power evidences the lack of authorized power.

What our brief institutional analysis indicates is that women are low in power in all major institutions in the West. This structural basis of low power is reinforced by the day-to-day interactions with women who devote themselves to the home, who do not seek careers, and who pursue positions traditionally occupied by women, like secretary, nurse, or public school teacher. One should not lose sight of the fact that men pick up these gender perceptions via social interactions with traditional women as well as by traditional views being passed down to them in the male culture.

Many employers still view women as earning "extra spending money" and lose sight of the millions of women who are the sole support of their families. This is a sort of Catch-22 situation wherein if women strive to break into high-status professions, they are blocked by the traditional expectations; and if they do break into such professions, they are not afforded fully equal status and are often relegated to the lower echelons of that profession. It seems that women must first be viewed as equal before they can gain equality.

One illustration of the Catch-22 status of women in the Western world can be seen in the status of female medical doctors in the Soviet Union. In part due to the great loss of males during the Second World War, the Soviets encouraged women to enter the medical profession and become general practitioners. Women did enter and now comprise about 80% of the general practitioners. One might surmise that this would raise the status of women, but what happened was otherwise: The status of general practitioner went down as the percentage of women in that role increased. Today, the general practitioner in the Soviet Union earns less than an industrial worker. Yet in accord with their broad institutional power, males are still the surgeons and hospital administrators and earn much more income.

What appears to have happened in the preceding instance is that since women were viewed as unequal to men, when they entered the profession of medicine, instead of raising the female status, the worth of their part of that profession declined. My conclusion from this is that a group that wants to increase its power must somehow first convince those in power that it deserved more than it has. This is not an insurmountable obstacle, but it clearly complicates the movement toward female equality in the Western world. This is not the place for discussing educational and other strategies for equalizing gender roles. For our purposes it is sufficient to make the point that in the Western world the female gender role has less authorized power than the male gender role in all the major institutions.

A TEST OF A THEORY OF GENDER INEQUALITY

Now let us develop a macro or overall view and see how the power of each gender reflects the general type of society. Most of the anthropologists who have written on gender power have noted that there are significant changes when one moves from hunting and gathering societies to agricultural societies.13 Following up that lead, I examined the data available on the 186 nonindustrialized societies in the Standard Sample. My basic assumption was that the greater the male power and status in a society, the more likely female status and power would be low. This assumption states that whoever is in power will rule both genders due to their integrated roles in that society. By status I mean prestige of honor. 14 Status and power can vary somewhat independently of each other. Think of college professors: They have high status but only modest power in our society. Nevertheless, generally status and power levels are closely related.

As a background for discussing my findings I want to mention the extensive study of the general status of women in nonindustrial societies done by Martin King Whyte.15 He examined 52 measures of female status in 93 of the societies in the Standard Sample. Given the lack of cross-cultural studies of gender power, this study of status is a strategic one for our purposes.

Whyte's results were in many ways inconclusive. He found that the 52 measures of female status fit into ten different scales, and these ten scales of female status did not relate to each other. One conclusion, then, would be that female status was a broad, multidimensional concept and no single way of measuring it would suffice.16 Remembering our earlier discussion about the vagueness of much of the data in the Standard Sample, one might also conclude that Whyte's findings were inconclusive because the data were not precise enough to reveal what interrelations did exist among these ten scales measuring female status. In any case, for my purposes I needed a simple measure that would at least get at one of the important aspects of female status. I could not get involved in the intricacies of precisely how to measure all the key aspects of female status.

I chose one of Whyte's female status questions: "Is there a clearly stated belief that women are generally inferior to men?" Out of the 93 societies he studied, 27 held such a belief and 66 did not .17 These 27 societies probably represent those societies with the very lowest female status, for we know that male status is higher in virtually all societies; and so those with this public belief probably represent those "lowest" on female status. This should highlight what differences exist and set the stage for others to specify further whatever relationships were found. I searched for what other societal characteristics went with the inferiority beliefs and in that way sought a better understanding of how those inferiority beliefs develop.

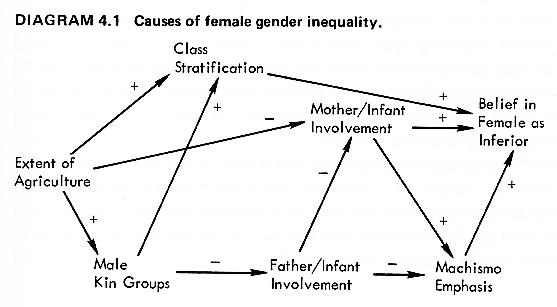

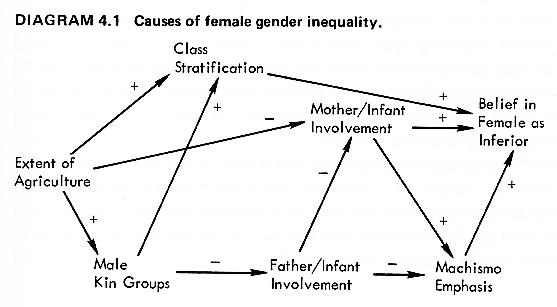

Diagram 4.1 presents the six societal features that comprise my explanation of how such beliefs in female inferiority develop and are supported.

The reader should be aware that the terms positive and negative refer to the direction of the relationship and not the strength of it. A negative relationship can be just as strong as a positive one. This causal diagram, like the ones in Chapter 3, presents changes through time going from the earliest events at the left to the most recent one, which is being explained, at the right of the diagram. It is really very easy to read - just don't let yourself get scared off by the initial complexity.

Now, a few words about the theory underlying this explanation. As noted earlier, almost all the writers on female power and status posit that the development of agricultural societies led to a significant drop in female power and status. The reasoning is that agriculture leads to a greater dependence on cooperative male labor and that is one factor promoting male power. The dependence on male labor results, in part, from the physical effort needed in agricultural societies that use the plow. Relatedly, agriculture emphasizes the value of male children and pressures the female to produce such valued agriculture workers.

In addition, agriculture leads to the development of more complex societies. The basic reason for this is that agriculturally based societies are capable of

DIAGRAM 4.1 Causes of female gender inequality.

|

producing surpluses in food supplies; that means much larger and more stable populations can be supported, and that increase in numbers adds complexity to the social organization. As a consequence there is a development of sharper social class distinctions in agricultural societies. In good part this is due to the development of more specialized political systems, as well as to the opportunity for accumulating wealth because of agricultural surpluses that can be bartered to others.

As these changes occur, women are increasingly excluded from leadership positions in these complex political and economic structures and are instead segregated into the domestic sphere or into subordinate farm labor. The end result of this less central societal role of females is a decline in the status of females from what it was in hunting, gathering, and horticultural societies.

I tested part of these ideas by using measures of the presence of agriculture, the event of male kin groups practicing patrilineal descent and patrilocal residence, and the development of highly stratified societies. These forces were measured by the first three variables to the left in the diagram. I also wanted some measure of gender roles that would indicate the extent to which women and men were involved in caretaking and companionship with infants. I felt this would indicate whether women were segregated from the center of power by their family commitments. I found two such variables in the Standard Sample (they are next in the diagram). Finally, I felt that a machismo18 attitude stressing male physical aggressiveness would also be a likely predictor of a belief in female inferiority.19

When I looked at the results of my causal analysis, I was truly surprised that the data so clearly were congruent with my expectations. The results did add specificity regarding how these six causal variables interrelate with each other as well as how they produce the belief in female inferiority. Given the limitations of the cross-cultural data, I did not expect to find any such clear pattern emerging. A sharp causal pattern usually does not emerge from vague codes because such codes may not clearly represent what they are purported to measure. Only very powerfully related variables would show through the fog of such imperfect codes, and so I was not optimistic. Yet the causal analysis revealed a pattern of relationships among the seven variables that was indeed impressive!

The lines in this diagram represent all the significant correlations among variables found in the statistical analysis of the data. Note that many possible lines relating these variables are not present. There are 21 possible interrelations of these seven variables as they are presented here. Of those 21 possible relationships, 11 showed themselves to be statistically significant. Most importantly, almost all of the 11 relationships that did meet the statistical standards and are in the diagram strongly supported my expectations.20

The order of the variables represents what I felt to be a time sequence of events starting with the advent of agriculture and ending with a belief in female inferiority. To my knowledge this is the first time such an extensive test of crosscultural data has been used to examine in a causal analysis this entire set of widespread beliefs about social changes in female status.

The results in Diagram 4.1 do show that, as expected, the advent of agriculture increases class stratification and male kin groups. In turn, male kin groups seemed to encourage greater class stratification, as can also be seen in the diagram. In addition, these male groups lower the likelihood that fathers will be involved in the care of their newborn, and that in turn increases the likelihood that mothers will be involved in the care of the newborn. Finally, one can see by the lines connecting mother- and father-infant involvements to machismo that the less fathers are involved in infant care and the more mothers are, the greater the level of machismo in a society.

One causal line may surprise the reader - that is the negative relationship of the advent of agriculture with mother-infant involvement. I had not expected this relationship, but I believe it may reflect the fact that in agricultural, as compared to, say, hunting societies, the greater food supply supports higher population densities. This means that women in agricultural societies are encouraged to have more children. Relatedly, the greater number of children may necessitate that others such as older children and grandmothers take on a share of the caretaking and nurturing of infants. Thus, even though mothers are still heavily involved with infants, a higher share of the total nurturance of these large families will be done by others. Finally, it may well be that in agricultural societies women are assigned additional minor economic tasks by males. This, too, would lead to mothers' seeking help in infant care from others.

The diagram presents a way of understanding the societal factors that promote male power and status over female power and status. There are surely other factors, but they are not represented in this diagram because I had to restrict myself to what variables were measured and were useable. Despite this restriction there are in the diagram many places for intervention should one wish to change attitudes toward females. Consider the impact of changing the emphasis upon male groups (in work, in descent, in residence) or the impact of increasing the female's chance to enter more fully the economic and political systems. In fact, these changes are precisely the sort of alteration that have occurred in the Western world in the twentieth century. They have been accompanied by a rise in female status and power, which further supports our theory of the societal causes of female status.

I must qualify any bald economic deterministic interpretation of these findings. Diagram 4.1 does not indicate that the economic change-in this case to agriculture-is the only factor that will bring about the outcomes in other variables. The findings do not preclude changes due to warfare, new value systems, or new political systems from also producing similar changes even if the economic system were unaltered. In my discussion of Diagram 3.1, I noted that agriculture was not a powerful determinant of changes in the importance of property nor in changes in the presence of male groups.

The key point here is that anything that increases class stratification and male groups will likely have similar outcomes in the other variables. Further, agricultural systems are varied, and not all changes toward an agricultural system will produce the same outcomes. It depends on, among other things, the amount of geographic and social mobility involved in that particular type of agriculture.21 Agriculture that involves geographic mobility would not encourage the formation of stable social classes.

The economic system is a pragmatic system, easily changed in most societies compared to religious, political, or family systems. Thus, it is often the economic system that initiates change. The role of the economic system is nevertheless a matter to be investigated rather than a foregone conclusion. Today many Marxists would also agree to that caution.

One other important theoretical implication of this diagram requires some comment. Examine the relationship of mother-infant nurturance to the emphasis on machismo and to the belief in female inferiority. The diagram indicates that the more the mother nurtures infants, the stronger the emphasis on machismo and the stronger the belief in female inferiority. Start at the left of the diagram and trace the lines leading into mother-infant nurturance. You will find that as agricultural tendencies increase, so do the strength of male kin groups; and as that increases, the father-infant involvement decreases; and that, in turn, increases the mother-infant involvement.

Now return to the connection of mother-infant involvement to machismo and the belief in female inferiority. It seems apparent that, given the pathway leading to mother-infant involvement, the reason for this variable relating to machismo and to the belief in female inferiority is that this measure of mother-infant nurturance is in part an indirect index of a male-dominated society. In such a society the mother will nurture the infant and will likely socialize the child in values and behaviors that will maintain the dominance of males. In this sense the mother-infant nurturance will emphasize machismo attitudes and promote a belief in female inferiority. Of course, not all societies that stress mother-infant nurturance are high on male dominance. Here, as elsewhere, the parts of a society can be put together in many ways. However, on the average, our statistical results indicate that such a custom of mother-infant involvement reflects male dominance in a society.

Some psychologists might examine the relationships of the mother-infant nurturance variable and develop psychoanalytic reasons why mother-infant involvement leads to an emphasis on machismo and a belief in female inferiority. Science generally operates on the principle of parsimony sometimes known as Ockham's razor, which favors the simpler explanation where there are several explanations put forth.22 I believe the simpler explanation is that such relationships are part of the overall pattern that makes up a male-dominated society. I do not believe that the involvement of the mother in infant care, per se, is what is causally important. The key is that mother-infant involvement is one way of freeing males for more powerful and prestigious positions in society. Therefore, in male-dominated societies that type of female gender role will be encouraged .23 At the same time that type of society will encourage the mother to pass along that society's male-dominant values even if they deprecate the female gender role. In this fashion, the tie of mothers to infants promotes a belief in female inferiority in particular types of social systems.

THE LINKAGES OF POWER, KINSHIP, AND GENDER

We have presented a general theory purporting to explain partially the relative power and prestige of males and females in different types of societies, but gender roles are themselves in large part a reflection of the kinship system in a society. Diagram 4.1 shows kinship linkages in part through the male kin groups variable, which measures partrilocal residence and patrilineal descent. Such measures inform us of the important consequences of strong male kinship ties measured by descent and by where one lives after marriage. Still, more intimate knowledge of kinship will assist us in understanding how the influence of the broader societal structure makes its way into gender roles. In all these linkages involving kinship and gender, the power dimension is significantly engaged. Follow along with my illustrations, starting with one very interesting culture, and I will try to clarify my meaning.

The Tiwi are a fascinating culture existing in Melville Island, North Australia. They will help us illustrate the ways in which kinship organizes our gender roles in a moderately male-dominant hunting society. The kinship system in this society has been extensively studied, most recently by Jane Goodale.24 The entry point for our purposes is the custom for the maternal grandfather in this society to arrange for the marriage of his granddaughter before she is ever born.

Female children are married from the moment they are born. When a female child reaches puberty and has her first menstrual period, her father will pick a son-in-law for her. One unusual feature of his choice is that the man he picks as his daughter's son-in-law will often be ten or twenty years older than the daughter who will be that man's mother-in-law. The father promises that all the female children his daughter bears will be given to the son-in-law as wives (Polygyny is accepted in this society and in about 75% of all the societies in the nonindustrialized world.) In return the son-in-law promises to help supply food for his mother-in-law and from then on will live in her camp.

Let us follow through the events after the birth of a female child to this man's mother-in-law. At age 7 the child is sent to live with her husband (the son-in-law) as his wife. The husband is often 30 or more years older than his 7 year-old bride, but both he and the child bride are prepared for sexual relations to occur usually within a year. Like the Lepcha, whom we discussed in previous chapters, the Tiwi believe that having intercourse at these early ages encourages female puberty. Without such intercourse young girls are believed incapable of developing breasts, pubic hair, hips, and menstruation. Thus, sexuality between an adult husband and a child bride is an accepted custom in this society.

When this child bride begins to menstruate, her father will pick a son-in-law for her, and this man will marry her female children and reside near her and help her. The process continues generation to generation. Note that under this system all girls are married before they are born, and so premarital sexuality is impossible for females in this type of society.

Interestingly, due to changes in husbands, the wife will eventually end up being older than her final husband. This is so because the Tiwi, like most nonindustrialized cultures, have the levirate custom, which means that when the husband dies, his younger brother becomes her husband. Since her first husband is much older than she, he will likely die first. After two or three such brothers die, she may end up with a husband who is younger than she is.

Marriage for a male is an achievement - the more wives, the more power. For a woman it is a fact of life - she can have only one husband at a time, and her power comes not from many mates but from residing near her mother, to whom her husband is indebted. The descent group for the Tiwi is thus matrilineal, and the residence group will consist of females related through their mother's line plus their husbands, who as sons-in-law are also living there. (This is matrilocal residence.) However, the Tiwi also belong to a patrilineage through which all their land is inherited. In this way there is a relatively close balance of power between the genders. A female has the support of her husband and her son-in-law and lives in her home village. A male through his male kin controls ownership of the land and arranges the marriage of his granddaughters to his advantage by often linking them to his nephews.

Note how the nature of the kinship system defines certain key aspects of gender roles. Kinship determines who arranges the marriage and what the rights and duties of those involved will be. Those involved are males and females; thus, by defining marriage roles gender roles are also defined.25 Further, the specific ways the kinship system is structured determine the balance of power between males and females. If the descent were patrilineal and no labor was owed to mothers-in-law and land was fully controlled by males, then the gender differences in power would be much greater than they are among the Tiwi.

To recapitulate, kinship systems must define how males and females interrelate, and the particular design chosen reflects the power of each gender. This power differential can be causally traced, particularly to key features of the economic and political systems. To illustrate, if males work the land together, then it is highly likely that descent will be traced through their line and they will reside together after marriage.26 If females work together, then it is more likely that descent and residence will be centered around females. Political influence from outside the society can also affect gender power. Etienne and Leacock assert that European colonists strengthened male power in the colonized societies by projecting their own notions of male dominance and dealing mainly with the males in the conquered societies.27

One additional way to illustrate how kinship, gender, and power are linked together is to examine further matrilineally organized societies. I will do this in general, rather than looking in depth at any one society. Matrilineal societies are organized around descent through one's mother's line and usually are more gender-equal than patrilineal societies.

First, we should here be sure the reader is aware that matrilineal societies are not matriarchies. That is, they are not societies in which women have the dominant power. In fact, one of the intriguing power findings is the lack of any society in which women have more normative power than men.28 There is also no evidence that there ever was such a society.

The Amazon society is a mythological society of women who supposedly removed one breast in order to permit them to shoot their bow and arrows with less obstruction - hence the name a(without) mazon(breast). Lest I be thought of as imposing this view, let me quote some of the main researchers on this point.29

It is true that we know of no society in which women have been dominant over men in political life generally, i.e., there have never been any true matriarchies. (Whyte, 1978: p. 6).

Although matrilineality has important consequences for women and can afford them greater power, influence and personal autonomy than patrilineality, it has not given rise in any known societies to matriarchy. Patrilineality is, however, sometimes associated with patriarchy. (O'Kelly, 1980: pp. 113-114).

A survey of human societies shows that positions of authority are almost always occupied by males. Technically speaking, there is no evidence for matriarchy, or rule by women, Amazonian or otherwise. (Martin and Voorhies, 1975: p. 10).

Women either delegate leadership positions to the men they select or such positions are assigned by men alone.... Since women are the potential bearers of new additions to the population, it would scarcely be expedient to place them on the front line at the hunt and in warfare. (Sanday, 1981: p. 115).

I stress the consensus on this point predominantly because there are those who believe they must support matriarchy as real in order to argue that women are the equal of men. As I have argued earlier regarding the flexibility of biological differences, there is no empirically based logic that forces this conclusion. The reality of gender equality on our planet seems to be that societies range from strong male dominance to close to gender equality. The female-dominant end of the continuum is literally unoccupied. Many explanations have been offered: greater male strength, female restrictions due to childbirth, lesser aggressiveness of females, and greater hunting ability of males. Note that whatever legitimacy these explanations may have had in our distant past, none of them seems very convincing in modern industrial society. In my judgment a matriarchal society has its greatest possibility in the modern world. The talents we stress today in the West are equally achievable by males and females, and so in some societies females may well gain greater power than males.

Now, let us examine matrilineal societies in general. Many of these societies are horticultural and involve women working together in important economic undertakings. One of the first things that puzzled anthropologists was how male dominance was achieved in societies where descent was traced through females. In such a society children belong to the wife. This has been called the matrilineal puzzle. The best answer to this puzzle has, in my opinion, been put forward by Alice Schlegel30. She points out that matrilineal societies do generally afford women higher status than patrilineal societies; but, she adds, there are two types of male roles that prevent full equally or female dominance from occurring: husband roles and brother roles. Her thesis is that in matrilineal societies female power is compromised by the husband and brother controlling the women who are wife and/or sister to them.

A brother belongs to the same descent group as his sister, for they descend from the same mother's line. Thus, he will usually have an important role in his sister's life. In the Trobrianders near New Guinea, whom we have discussed before, the brother supplies half the food his sister needs, and he socializes her children into the customs of their lineage.

The brother and the husband will further control the wives in a matrilineal society by picking the mate their children will marry. We saw in our discussion of the Tiwi one unusual way that male control operates via a grandfather picking a mate for his unborn granddaughter. Schlegel examined 66 matrilineal societies to see exactly how mate choice worked. In general, where husbands have the dominant power over their wives, this shows itself in the marital union of the daughters from that marriage to the husband's sisters' sons (matrilateral cross-cousin marriage). In societies where the brother dominates his married sister, the brother marries the sons from his marriage to his sister's daughters (patrilateral cross-cousin marriage ).31

In both cases the male (husband or brother) is combining the domestic group he controls (wife or sister) with a group in which he has a strong interest (his sister's sons or his sister's daughters). The marriage of this second generation combines his descent group (via his sister's children) and his ties to his wife (via her children) and thereby integrates the male's power in that matrilineal society. By such marriages the male overcomes his not belonging to his wife's children's lineage and asserts his authority about whom the children of his wife shall marry. This is one way that males in a matrilineage compromise the female power that comes from having a female descent system. The interrelationship of kinship, gender, and power is highlighted by Schlegel in this analysis of matrilineages. Her analysis points out how the type of kinship tie that goes with matrilineal descent can be used to pressure toward specific roles of males and females in marriage. These resultant types of marriages shape the relative power of each gender.

The partial economic bases of kinship and gender are equally obvious in Schlegel's account. It is the type of economic system that helps structure the specific type of kinship system. Matrilineages are common where women work together or where women's work is important, as in horticulture. Two thirds of the 66 matrilineal cultures examined by Schlegel were horticultural. The centrality of male groups even in matrilineal societies is evidenced by the fact that when women in these societies bring husbands to live with them, the distance from the husband's home is most often slight. This makes it easy for the husband to continue to work and interact with his sister in his own lineage. This custom indicates that male relationships are viewed as important even in matrilineal systems. In contrast, in patrilineal systems, where men bring wives to their parent's area, the distances are often great. This illustrates a discounting in those societies of the economic importance of female labor and of their continued interaction with their kin.

An illustration from the People's Republic of China (PRC) may even more clearly drive home the power of the economic system in structuring kinship relatonships. The PRC is a patrilineal society, but it clearly illustrates my point regarding matrilineal societies. During the Great Leap Forward (1958-61) the communist government in the PRC sought to create greater gender equality by breaking up the patrilineages that used to work the farm lands.32 They felt that as long as these male groups existed, females would not gain equal economic power. But the outcome was disastrous to productivity, and the communist leaders reestablished the patrilineal work groups in order to maximize output. The members of a lineage knew and trusted each other and worked well with each other. This occurrence further supports the power of the economic system to organize the kinship system and also highlights the importance of kinship organization for the economic system. These interrelationships are further documented in Diagram 4.1 in the relationships that were found between agriculture and male kin groups. For simplicity's sake I have made all these causal relationships one way. Reality, in most cases, will involve two-way causal relationships. I have chosen to highlight the dominant direction only.

POWER AND SEXUALITY

We have linked power to gender and kinship, but there remains the clarification of the linkage of power directly to sexuality. To accomplish this I will start by asserting the proposition that powerful people seek to maximize their control over the valuable elements in their society. If this is so, then it follows that since sexuality is universally considered important, it will be one of the life values over which people in power will seek to gain control. Further, it follows that if males have more power than females, they will seek to gain a larger share of whatever is sexually valued in that society.

This relationship of power and sexuality can be seen in comparing sexual permissiveness for females in matrilineal with patrilineal societies. We saw the integration of power and sexuality in the last chapter in Diagram 3.2, which showed that as female premarital sexual rights rose, so did female willingness to express marital sexual jealousy. In general, matrilineal societies allow greater premarital and extramarital sexual freedom for women than do patrilineal societies. Relatedly, it is also the case that matrilineal societies lean more toward the gender-equal end of the continuum than do patrilineal societies. So, it does appear that, everything else being equal, the greater the power of a gender, the greater the sexual permissiveness allowed that gender.

This relationship is relatively easy to demonstrate in nonindustrialized societies of just a few hundred people. When you examine societies of a few hundred million people - like our own - many other factors complicate the relationship. Not the least of these other factors is the different values that may prevail in various segments of a complex society. In such a complex society, "everything else" would not be equal, and one would have to compare people with the same set of values and then see if the more powerful were also the ones permitted the greatest sexual rights. I assume that within a group of Americans with similar ethical values, those with the most power will have greater ability to obtain what they wish. Even if in a particular group sexuality is circumscribed by all kinds of restrictions, those who are most powerful in that group will be most likely to be able to obtain whatever the acceptable level is - and perhaps a bit more.

Probably the clearest support for this general proposition concerning the relation of power to sexuality comes from a comparison of male and female sexual rights in cultures around the world. The double standard that affords males greater sexual rights than females is widespread. Males are more socially powerful than females in almost all societies, and they do indeed have greater sexual rights than females. More than that, the greater power of males seems to lead to attempts by them to control the sexuality of their wives and other women (see Diagram 3.1).

In part this is so because of the importance of sexuality and the consequent tendency of sexuality to link with jealousy.33 Powerful males, as well as others, will seek not only to obtain sexual satisfaction but to control the sexual access by others to those who are important to them, such as wives, daughters, and sisters.34 Being powerful, they have the greatest ability to exercise such control. At the same time, these males seek sexual satisfactions for themselves, which means possibly violating the sexual boundaries set up by other males around their wives, daughters, and sisters.

There is present here what I call the double-standard dilemma of desiring to protect one's sexual partners from others but also wanting to have additional sexual partners for oneself. Societies have tried different solutions - none of them fully resolving this dilemma. Some societies set up a different class of female partners, such as occurs in prostitution or the use of slaves or lower-class female partners, but the availability of female sexual partners in one's own social class is usually too convenient to be ignored.

This situation then leads to a cloak of secrecy about sexual affairs and to guilt feelings if one violates the protective norms. It puts males in potential conflict with each other as they seek partners willing to violate the jealousy boundaries. Men are at the same time striving to enforce their own jealousy boundaries around their women. Clearly, the fact that it is males who are seeking to control female sexuality is itself a statement of a significant power differential.

One of the best-known anthropological theories concerning female sexual rights stresses the role of marriage gifts. The theory has been proposed by Jack Goody. He proposes that a more open acceptance of female premarital sexuality goes with bridewealth marriage systems. In bridewealth exchange systems there is a modest wedding gift, often in the form of cattle, given to the bride's family upon marriage. This custom is common in Africa. The wealth gained is soon transferred when a brother must use it to give as a present to his bride's family. Such exchanges consist of modest amounts of wealth and do not upset the division of wealth in a society. As noted, what you receive for a daughter must generally be used to obtain a wife for your son.

The ultimate bridewealth exchange is wife exchange, wherein you send your daughters to marry into another group and another group's parents will send their daughters to marry into your group. Here, too, Goody would claim there is no major economic alteration. Rather, as Claude Levi-Strauss has pointed out, such wife exchange serves as a method for linking two groups together who may be useful to each other in times of stress.35

Goody feels that cultures that engage in bridewealth exchanges of any kind are relatively sexually permissive because the daughter's value in such exchanges does not need to be enchanced by her virginity, for there is little of economic value at stake. Once again, the reader should be aware that the very fact that daughters and not sons are exchanged in marriage is testimony to the relative power and importance of females and males in those societies.

There is a second form of marriage gift that Goody stresses as the key basis for restriction of female premarital sexuality. That is a dowry system that consists of linking the woman's wealth to her husband's wealth. In such a system the daughter is in reality receiving her inheritance prior to the death of her parents. A great deal of wealth can be exchanged by this custom, which can lead to a consolidation of wealth in a few families. The dowry system does go with a monogamous marriage system, for a few parents would want to be just one of several bride-parents - all of whom are giving wealth to one man. They would not wish to share their wealth with the children of other parents. Dowry is also more likely to be found in a stratified agricultural society where wealth can be accumulated. We already know (see Diagram 4.1 ) that such stratified societies are generally higher on male dominance than are simple, unstratified societies. The dowry custom is familiar to Westerners because it is part of our European heritage.

Goody argues that the presence of a dowry system means that the value of the female is being stressed. She is inheriting a large amount of wealth, and she can add considerably to the power and influence of her husband. In such circumstances the husband is going to want to be certain of the loyalty (perhaps controllability is a better word) of any future wife. Goody describes the situation as follows:36

If one is attempting to control marriage, it is important to control courtship too, . . . in upper status groups where property is more significant ... restrictions are likely to be placed upon contact between persons of opposite sex before marriage ... there will be a tendency to taboo sexual intercourse between them ... [but] there appears little reluctance for men to engage in sexual unions, as distinct from marriage, with women of the lower orders. It is the sexuality of their own sisters they are concerned to protect, and the notions regarding the purity of women that attach to caste systems and the concern with their honour that marks the Mediterranean world cannot be divorced from the position of women as carriers of property. (Goody,

1976: pp. 13-15)

Goody presents data indicating that premarital intercourse of women is restricted in 64% of the dowry societies but only in 40% of the bridewealth societies. Thus, evidence of a sort supports his view. However, in those societies that do not have any fixed rules of dowry or bridewealth, 59% restrict premarital intercourse, which is close to the dowry society's level of restriction.37 Another point to remember is that the majority of people even in dowry societies are poor and disenfranchised and are thus not involved in a dowry system.

In sum, then, I would accept the marriage-gift custom as one factor in the production of premarital norms, but I see it as more a reflection of a type of society than an important cause of our premarital sexual norms. I view such customs as outgrowths of a previously established gender-power structure rather than as a major cause in the establishment of a specific gender power distribution. By itself Goody's marriage-gift explanation is insufficient to satisfy our need for a theoretical explanation of gender power.

Regardless of how little explanatory weight we give to bridewealth and dowry systems, Goody does explicate the ways in which power relates to sexual customs. Goody spells out how the greater power of males operates to control the sexuality of females while still permitting sexual freedom to males. That situation of unequal sexual rights is, of course, the essence of the double standard. It exists in many cultures without the dowry system, and thus one should not conclude that the double standard is due to a fear of an illegitimate heir who may claim the family's wealth. We must remember that most people have very little wealth about which to be concerned. More importantly, the concern with out-of-wedlock births need not produce a double standard of sexuality. If gender power were equal to begin with, the effort to control pregnancy would not be imposed solely on the female.

One other area relating power to sexuality should be discussed. This area concerns sexual "abuse" by those in power. Even the powerful are restricted by norms concerning how they may exercise this power in relation to other people. In this sense, negotiation is at the heart of all sexual relationships. All societies place some limits on the use of force and fraud in sexual relationships.38 In sexuality we see such limitations, I believe, in some of our incest taboos. One consequence of a parent-child incest taboo is to prevent the sexual abuse of the child by the parent, who clearly has the ability to force sexuality upon the child. 39

Schlegel presents an illustration of this in her analysis of matrilineal societies. She found that in societies where the brother had greater power over his sister, there was a stronger incest taboo on brother-sister sexual relationships. Whereas in societies where the husband had greater power over his wife and children, there was a stronger incest taboo on father-daughter incest. This difference in strength of taboo by the power that brothers have over sisters versus the power that fathers have over daughters is instructive. In both instances, it indicates a protection of the weakest from the sexual abuse of power. The specific norms cover those situations with the highest risk that power will be used to force sexual compliance.

One way to make this point relevant to America today is to consider the new legal rulings on sexual harassment. Basically, what these rulings have done is to assert that a person may not abuse his or her power as a superior in a job situation by using that position to coerce sexual acquiescence. Once again, we see a situation in which limits are placed on how the powerful utilize their power in sexual situations. The attempt in all these cases seems to be to promote autonomy and prevent threat or force from being the pathway to sexuality. To be sure, the powerful still possess an advantage in obtaining what the sexual values allow in a society. But it does appear that the use of power is limited by the norms that function to restrain the exercise of power within the bounds of that culture's beliefs.

We must know the basic values and ideology of a society if we are to predict just what greater sexual rights power will bestow upon a person. No society permits even the powerful to do whatever they wish in sexual matters. This means that individuals need to learn to negotiate about sexuality just as they need to learn to negotiate in regard to other important areas of life such as seeking a job or a mate. In fact, some treatment programs for rapists and other sex offenders stress just such a development of a broader range of sexual negotiation skills.40

Each society sets up its sexual scripts regarding sexuality, but not all people internalize this in ways that are appropriate for their social setting. In addition, changes in personal sexual ideologies require changes in sexual scripts. When two lovers shift toward different concepts of the limits of force and fraud, for example, conflict is inevitable. In this sense there is a need for constant individual reappraisal of one's sexual scripts and the related negotiating skills one possesses. This is particularly so in a complex society such as ours, where our sexual scripts may differ considerably from those of others.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

Many writers on gender-role power have stressed that women exist in the domestic sphere and men exist in the public sphere.41 There is, of course, truth in this assertion. I have not explicitely developed that distinction because it would not add much to what I have already said and if stressed, can be misleading. The domestic-public distinction is often used to explain why males are more powerful - they operate in the public sphere. The problem with that perspective is that there are many male-dominant societies in which females do spend much of their time in the public sphere and do even produce most of the subsistence the society requires. Participation in the public sphere does not ensure gender equality. Surely this is the case in most Western societies. In the determination of power what is important is the control you have over what you are doing, not your productivity or the area in which it is occurring.

Power, as defined earlier in this chapter, is the ability to influence others. If women produce most of the subsistence but the control of what they produce is in the hands of men, who is the most influential? Slaves produced most of what Athens needed in the fifth century B.C., but they hardly were in control. In short, the domestic role of women is but one indicator of a lack of power. The generic index of power is, as noted, not only the sphere in which you operate but also the control you have over what you are doing. The powerful have the choice to do many things in many places, whereas the powerless must do the specific things they are assigned, whatever and wherever that may be.

Peggy Sanday has a somewhat different position on male and female power, one that expresses an interesting viewpoint.42 Sanday stresses that societies value the power to give life as well as the power to take it away, and thus women as well as men are highly valued. Power, she believes, goes to the gender that embodies the forces upon which people depend for their needs.43 People may take what she calls "an inner orientation," which relates nature to being female, or "an outer orientation," which focuses on the outer world where hunting, killing, and the pursuit of power occur and is associated with males. She contends that when cultural change requires aggressiveness and competition, the outer orientation is encouraged and males will dominate a society. When there is easy access to life requirements, then the giving of life and the inner orientation will assume a higher position and there will be more equality of the genders.

I have a mixed reaction to this not uncommon thesis. On the one hand, it sounds reasonable, for we do recognize males to be more aggressive and centered on the outside world, whereas females appear to be more nurturant and child centered. Yet, on the other hand, Sanday's thesis depends on accepting such gender differences as fixed - otherwise her theory cannot predict who will be more powerful. I do not accept such a fixed view of gender differences. As I discussed at the start of this chapter, training shapes whatever basic genetic potentials we have, and aggression and nurturance are always culturally designed.

I would add that were some environmental stress to occur in a society that was already gender-equal, I doubt if her theory would hold up. That is, I doubt if males would take over such a society and become dominant. I believe it is the prior presence of such male dominance that makes it likely that competition will increase that dominance. In most instances males are already in the position of power brokers before the crisis starts. In addition, even peaceful, noncompetitive societies often exhibit male dominance of some degree, and that is difficult it explain with her orientation.

Overall, I believe that many of the positions such as Sanday's "inner-outer" and the "domestic versus public" approach unintentionally accept too much of a fundamental male-female difference. I cannot deny the biological factors are involved in human behavior, but I believe the cross-cultural variation we see shows that such differences are malleable.44 My position asserts that a biological potential never expresses itself without being shaped by the lifestyle of a particular culture. Therefore, genetic potential is quite flexible and should not be viewed as necessitating sharp gender differences, as implied by Sanday's inner- and outer-orientation notions. What gender differences exist are there because of the cultural shaping of our human potential, not because of any fixed male and female "traits." I suspect that Sanday, too, would accept such flexibility, although her explanation, perhaps inadvertently, assumes inherent male-female differences.

It is puzzling that even some feminists seem not to question so much of the immutability of gender behavior. In this regard the position of Friedrich Engels is close to mine. Engels asserted that the cause of male dominance would be found in the change in society toward exploitive productive systems and not in the genetic makeup of males.45 On this same point, the primatologists tell us about the common presence of competition and assertiveness in female primates.46 They further point out how female primates are the stable core of a primate group and how they often appear to be influencing the behavior of males. If we believe our human biological heritage has any similarities to our primate cousins, then such reports should give us pause and raise questions about our views concerning the immutability of aggressive-nurturant differences between males and females.

In conclusion, Whyte's research on 93 Standard Sample societies did not find a significant correlation between male dominance and the frequency of warfare that Sanday's thesis assumes to be present. In addition, hunting societies stress the male's aggressiveness in the hunt and his competitiveness, and yet they are generally the most gender-equal of all human societies.47 All these findings make me feel that we should not endorse any stereotypes, new or old, concerning inherent male-female differences and the necessary consequences of them.

I see the human condition as presenting us with choices far beyond those we have already taken. Therefore, I see gender roles as limited by the interdependencies of a social system more than by any biological forces. By that I mean that if we want to explain gender inequality, we should not refer to innate differences, but attend to the degree of male control of key societal institutions. To illustrate, male control of the political and economic institutions makes the occurrence of a gender-equal marital relationship problematic. Examining these limitations of one systemic structure on another are where we should be placing our research efforts if we are to learn what produces the basic differences in gender roles in human societies. Whyte's research on sources of female status informs us that these causes are far more complex than we may think. That is what we must pursue if we are to find the answers to societal causes of differential gender power and prestige.

My basic purpose in this chapter has been to show how our gender roles reflect the power system in the broad society and in the relevant kinship groups that exist. From there it is but a short step to discern how such power can affect our sexual behaviors and afford us differential access to the sexuality available in a particular society. Finally, we need be aware of the way basic values structure the legitimate areas of sexual rights, even for the powerful. In terms of our basic theory concerning universal societal linkages, the power structure as reflected in gender roles is everywhere a determinant of the sexual customs of males and females and thus is the second of three vital linkage areas.48 We have already discussed kinship as a linkage to sexuality both in terms of jealousy and now in connection with gender. Ideology is the third societal linkage, and we will begin our discussion of that crucial aspect of our social lives in the next chapter.

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

1. I computed these percentages using the codes in the original data from the 186 cultures in the Standard Sample. See Appendix A for a list of the exact questions used. For an overview of these codes and this sample see

Murdock, George P., and Douglas R. White, "Standard Cross Cultural Sample," Ethnology, vol. 8 (1969), pp. 329-369.

For some interesting cross-cultural work on gender roles see

Aronoff, Joel, and William D. Crano, "A Re-examination of the Cross-cultural Principles of Task Segregation and Sex Role Differentiation in the Family," American Sociological Review, vo. 40 (February 1975), pp. 12-20.

Crano, William D., and Joel Aronoff, "A Cross-cultural Study of Expressive and Instrumental Role Complementarity in the Family," American Sociological Review, vol. 43 (August 1978), pp. 463-471.

2. Mead, Margaret, Growing Up in New Guinea. New York: Morrow, 1930.

3. Of all sociologists Alice Rossi has written the most about the biological factors that contribute to gender differences. She argues for more of an integrative approach between sociology and biology. She spoke of this in her 1983 presidential address to the American Sociological Association. I do believe that she overemphasizes the power of the biological and neglects the explanatory power of the sociological. Surely the phenomena of sociology and biology are intermeshed, but the task of every science is to specialize in a particular abstraction of reality rather than trying to present total reality, whatever that may be. My own belief is that we do the best for science when we develop our own field and use other fields only to the extent that they clarify the development of our own specific level of explanation. Nevertheless, I do value her writings and list some here. I also include an article I wrote developing my point about the value of specialization inherent in each scientific discipline. I do believe, however, that applied disciplines, unlike basic science disciplines should be multidisciplinary. I develop this thinking in Chapter Eight.

Rossi, Alice, "A Biosocial Perspective on Parenting," Daedalus, vol. 105 (Spring 1977), pp. 1-31.

Rossi, Alice, "Gender and Parenthood," American Sociological Review, vol. 49 (February 1984), pp. 1-19.

Reiss, Ira L., "Trouble in Paradise: The Current Status of Sexual Science," Journal of Sex Research, vol. 18 (May 1982), pp. 97-113.

4. In 1974 Maccoby and Jacklin published a book surveying the scientific literature for any possible biologically based gender differences. One of their findings asserted the greater physical aggressiveness of males both cross-culturally and cross-species. They also found females better on verbal ability and males better on mathematical and spatial abilities. The evidence they present on differences in aggression is the strongest. A similar position on aggression is taken in the highly acclaimed cross-cultural study of gender by Martin and Voorhies. Many additional sources can be found in these two books.

Maccoby, Eleanor E., and Carol Jacklin, The Psychology of Sex Differences. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1974.

Martin, M. Kay, and Barbara Voorhies, Female of the Species. New York: Columbia University Press, 1975.

5. For comparisons of males and females with some attention to the role of hormones such as androgen, see

Beach, Frank A. (ed.), Human Sexuality in Four Perspectives. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer, The Woman that Never Evolved. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Mitchell, Gary, Behavioral Sex Differences in Nonhuman Primates. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1979.

Symons, Donald, The Evolution of Human Sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Zillman, Dolf, Connections Between Sex and Aggression. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1984.

Bandura, Albert, Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1973.

6. For a fascinating account of "extra" genders in cultures around the world, see "Supernumerary Sexes," Chapter 4 in

Martin, M. Kay, and Barbara Voorhies, Female of the Species. New York: Columbia University Press, 1975.

7. There is also the case of transsexuals. A transsexual is a person of one genetic sex who adopts the gender usually associated with the other genetic sex. The occurrence of such people throughout history indicates the disjuncture of genetic sex and gender. Recall our distinction of the terms sex and gender, which we discussed in Chapter 2. Without that terminological clarity we would have difficulty discussing the transsexual or "extra" gender phenomenon. For an early statement on transsexualism, see:

Benjamin, Harry, The Transsexual Phenomenon. New York: Julian, 1966.

8. The question of interpersonal power is a complex one. The definition I use is the one generally accepted by sociologists. For an introdcution to the study of male-female power, see

Cromwell, Ronald E, and David H. Olson (eds.), Power in Families. New York: Halsted Press, 1975.

9. I am presenting the basic approach of sociologists to the study of stratification and power. In addition to the four institutions I listed in the text of this chapter, other sociologists include the education institution as a universal institution. Most introductory sociology texts cover this area. For a more advanced illustration and analysis of inequality in America see

Nelson, Joel I., Economic Inequality: Conflict without Change. New York: Columbia University Press, 1982.

10. One of the most incisive commentators on the family institution from the point of view of the law is Lenore Weitzman. She points out the assumptions made in the law about the rights and duties of husbands and wives. I recommend the following: