|

THE DELICATE BOUNDARY

Sexual Jealousy

POPULAR EXPLANATIONS OF SEXUAL JEALOUSY

THE SOCIAL NATURE OF JEALOUSY

IS MARITAL SEXUALITY SPECIAL?

LOVE IS NOT ENOUGH

INTRUSION AND EXCLUSION: THE STRUCTURE OF JEALOUSY

THE ACCEPTANCE OF EXTRAMARITAL PARTNERS

SEXUAL JEALOUSY OUTSIDE MARRIAGE AND HETEROSEXUALITY

MALE DOMINANCE AND JEALOUSY: CROSS-CULTURAL EVIDENCE

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

POPULAR EXPLANATIONS OF SEXUAL JEALOUSY

Probably the most popular view today about sexual jealousy pictures jealousy as due to personal feelings of insecurity as reflected in lack of trust, low ego strength, and excessive dependency. This is a psychological view, and it implies that one can overcome jealousy by altering those feelings of insecurity that lead one to feel threatened by an "outsider."

In line with this approach, Larry Constantine has proposed that one effective way to manage jealousy is to realize how unique and irreplaceable we each are.1 No one in the world is identical to any one of us (even identical twins have differences). Therefore, we need not be so concerned that our mates or partners will find someone who will replace us, for no one can really do that. This perspective, I contend, would satisfy only those who are desperately searching for reasons to feel more secure. Although it is true that we cannot be precisely replaced, it is equally true that we can be improved upon. To be sure, we may be unique, but not necessarily in the most admirable fashion. This orientation is thus hardly a consolation to those realistically searching for reasons to feel secure.

Still, there is evidence that would support the connection of personal insecurity to feelings of jealousy.2 Insecure individuals may generally be near the top of the level of jealousy that is customary in a particular society, but my point here is that the insecurity level in a society does not establish the customary level of jealousy in that society. Accordingly, the limit of such a psychological perspective is that it does little to explain why societies relatively equal on level of personal insecurity can differ so much on jealousy expectations. To illustrate, my impression is that Spain endorses the expression of jealousy more than does Sweden. Can we simply say that this is due to a higher proportion of insecure people in Spain? I think not. Rather, the level of jealousy can be understood by reference to the norms of that society and to the ways in which important relationships are structured into the basic societal institutions. Psychological explanations would be valuable mainly for comparing individuals within one society or group. I believe a societal-level explanation, not a psychological explanation, is needed for understanding the variation in jealousy that exists among different groups of people.

Before putting forth my own view, let me deal with a competitive societal-level view. A traditional Marxist conception is that jealousy results from the capitalistic tendency to treat the person with less power as a piece of property that we possess and therefore have the right to control. This perspective emphasizes that husbands feel they own their wives' bodies, and this belief leads to strong jealousy reactions by husbands. I would not deny that there is an element of truth in such a Marxist perspective, but I would contend that it explains only a limited amount of societal differences in jealousy. I would prefer to accept the linkage of male power with male jealousy as the general proposition and not bind myself to the proposition that such male power expresses itself in a property view of women. That is but one way that male power may express itself. Such power may also express itself in the general attempt to achieve whatever one desires, and such desires may well include maintaining the emotional commitment of one's wife. Viewing women as property is not necessary as a means of exercising power. One can view women as subject to male control but as valuable creatures in their own right, with their own powers, who should be treated quite differently than one's property. Some Western societies have conceptualized women very much this way.

Let me elaborate. How do we explain jealousy in communal societies like the Israeli kibbutzim? They are not taught to conceive of people as property, for they are not capitalistic and they are communal. In fact, many of these kibbutzim are Marxist and would explicitly oppose such a property view of people. 3 Further, the property explanation would not account for jealousy in the many hunting and gathering societies that lack private property. Finally, in capitalistic societies property is controlled predominantly by males, and so even there how do we explain jealousy by females regarding their husband?

We in America surely live in a capitalistic society, and yet it would be a caricature of reality to state that married couples think of each other as property. Do we also think of parents and friends as property? We can become jealous about the actions of these people also. There was more truth to the "property" notion in the middle ages, when the doctrine of coverture demanded that upon marriage the wife turn over all her property to her husband. But that doctrine has little meaning in Western societies today. There surely are possessive attitudes and attempts to control a mate's sexual behavior, but I do not believe this is because we view our mates as our property. This is not to deny the importance of male power in the explanation of jealousy, but to assert that male power affects jealousy in more ways than the property view of women permits us to envision. Thus, it seems that the narrow property explanation of jealousy distorts reality to fit the procrustean bed of orthodox Marxist ideology. I will expand upon my own views and findings concerning how power affects jealousy later in this chapter.

THE SOCIAL NATURE OF JEALOUSY

In the interest of clarity it is always well to begin with a definition. From a sociological or group perspective, jealousy is a boundary-setting mechanism for what the group feels are important relationships. That is, jealousy functions in the social system as a force aimed at defining the legitimate boundaries of important relationships such as marriage. When those normative boundaries are violated, jealousy occurs and indexes the anger and hurt that are expected to be activated by a violation of an important norm.

Dovetailing with the societal-level definition, we can define jealousy from an interpersonal or social psychological perspective as a response to a socially defined threat by an outside person to an important relationship. 4 The knowledge that jealousy can occur is by itself a factor that other individuals have to reckon with if they seek to disturb the legitimate socially defined boundaries of an established relationship. Of course, there is no guarantee that because there are jealousy reactions, violations will not occur. Rather, jealousy norms are indicative of the existence of strong beliefs about the legitimate boundaries of a particular relationship.5

Finally, we can look at jealousy from a personal, that is, subjective, emotional perspective and define jealousy as a secondary emotion.6 That is, it consists of a situational labeling of one of the more primary emotions such as anger or fear. When one interviews people and asks them what they are feeling when they say they are jealous, they most often respond by saying they feel angry or fearful. It seems that when a felt threat to a marital sexual relationship is interpreted as jealousy, it is because that society teaches one to label as jealousy angry and fearful feelings that occur in such situations.

It is informative to note that in many societies around the world women are more likely to react to jealousy with depression and men more likely to react with anger. Several anthropologists have noted this gender difference. This is not surprising in a male-dominant culture, where one would expect women to turn anger toward themselves and thereby produce depression. However, even in more equalitarian societies it seems that the cultural emphasis on women not expressing aggression may prevail even if less common. Alice Schlegel, for example, in discussing the relatively equalitarian Hopi Indians in Arizona says: 7

Sexual infidelity is also regarded as a violation of trust, and the typical response to it, particularly among women, is despondency and depression.

(Schlegel, 1979: pp. 132-133)

In a recent study of seven European countries Bram Buunk found analogous differences between men and women.8 He reports that men were given more autonomy in all seven societies and thus were allowed to be more independent of the constraints of any relationship. Buunk reports that in the more democratic societies in his sample (the United States, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Mexico), women were given more autonomy than they were in the less democratic nations (the Soviet Union, Hungary, and Yugoslavia). Nonetheless, men were granted higher levels of free choice even in democratic societies. In part, the difference between the democratic and other nations was due to the greater affluence in the democracies, which produced an overall higher general belief in autonomy. These findings would lead one to believe that, in general, females would be less permitted to provoke male jealousy and also less able to restrain their men from actions that make women jealous. The feelings of powerlessness that this situation produces in women is likely a major reason for depression as a common female response to jealousy.9

I believe that boundary limitations on relationships apply to all relationships that are thought to be important in a culture, whether they are sexual or not. Close friendships are defined in terms of what interactions with others are acceptable.10 Kinship relationships, other than with mates, such as with parents and siblings are also defined in ways that indicate when each of those relationships is to have priority over other relationships. An illustration of how some relationships are given priority over others can be seen in cultures that have patrilocal residence in which the husband brings his bride to live in or near his parents' home. The husband's mother most often demands that the groom give first allegiance to her and not to the new bride. In our culture the marital pair would live alone and would generally give their relationship priority over relationships with parents. In both situations, any violation of those priority boundaries could lead to feelings of jealousy.

Our interest here, though, is not in all types of jealousy. Instead, we shall focus upon sexual jealousy in marriage. Nevertheless, what we say may well have applicability to nonsexual forms of jealousy as well as to sexual jealousy in homosexual and heterosexual nonmarital situations. I choose to focus upon marital relationships because I believe that sexual jealousy is universally present there. An even more important reason is that the marital focus reveals much about the nature of the close tie of sexuality to kinship in cultures around the world. Thus, by this exploration we gain further insight into one way that sexuality is linked to kinship structures in all societies.

The proposition I am asserting here is that all human societies are aware of sexual jealousy in marriage and have cultural ways of dealing with it. Furthermore, although some cultures have surely learned how to cope effectively with sexual jealousy more than others, no culture has learned how to eliminate sexual jealousy. It follows, then, that the societal linkage of jealousy to marital sexuality would not be an unknown connection in any culture, though the strength of jealousy and the value placed upon it do vary considerably for reasons we shall soon explore.

Why should there be a universal connection of jealousy to marital sexuality? One key reason is that, as discussed in Chapter 2, all societies place high importance on human sexual relationships. Now not all specific sexual relationships need be highly valued, but the high value of sexuality in general is supported everywhere. Given this fact, when we link sexuality with a kinship institution like marriage, which is also viewed as an important part of society, we make it inevitable that norms concerning marital sexual jealousy will evolve and will set limits on sexual relationships with outsiders.

Let me emphasize that a society can, and many do, define some nonmarital sexual relationships as unimportant and that in such relationships boundary limits are very vague and jealousy is unlikely to develop. The classic example would be prostitution. A man would not likely feel jealous if he saw a friend with the same prostitute that he had just left. Yet if a man saw his friend enter his house to have sexual relations with his wife, this surely would be evaluated differently. So it is predominantly those sexual relationships that are considered important that are ringed with the alarm system of jealousy.

The essential point underlying my thinking here is that since marriage and sexuality are nowhere matters of indifference, marital sexuality will be "protected" by boundaries "armed" with jealousy norm sensors. As the reader will soon discover, some of these boundaries include the acceptance of other sexual partners besides the mate; yet the priority of marriage is still promoted by these broader, but still clearly defined, boundaries.

Ralph Hupka's research on marital sexual jealousy in 92 cultures (80 of which are part of the Standard Sample) is the only extensive cross-cultural source of such data of which I am aware.11 One of the most powerful predictors of jealousy in his research was the emphasis placed on the importance of marriage. The greater that emphasis, the greater the jealousy response. In all 92 cultures, he found evidence of sexual jealousy in marriage. He reports that in all his cultures, the husband was permitted to attack his wife physically if he found her in the act of intercourse with an unsanctioned male. These findings support my assertions concerning the universal presence of marital sexual jealousy and its roots in the importance placed upon marriage and sexuality. We will, later in this chapter, use more of Hupka's data to try to account for differences in the extent of marital sexual jealousy in various societies, but for now let's examine the evidence supporting the universality of marital sexual jealousy.

In addition to Hupka's data, we can at this time further consider the universality of marital sexual jealousy by examining a few very distinctive cultures and some relevant marital systems to see if marital sexual jealousy fits into these societies. These societies are unusual enough to act as good test cases for the universality notion of marital sexual jealousy.

One such unusual Western culture is that of Inis Baeg, off the coast of Ireland, where Messenger informs us that sexuality is treated as extremely dangerous and as something to be discouraged and not openly discussed.12 Messenger believes that women in this society are generally not even aware of their potential for orgasm. In less extreme form this negative cultural approach to sexuality was widespread elsewhere in the Western world until a generation ago.

Remember that even in such a restrictive society sexuality is felt to be important; that is, it is a matter of some concern to the society even though that concern focuses on ways of controlling and restricting sexuality. In addition, that society, like all societies, values a marital union; and when its restrictive views of sexuality are linked with the importance the society places on marriage, we have the makings of a very strong jealousy boundary surrounding marital sexuality.

At the opposite end of the permissiveness continuum are the many societies all over the non-Western world where sexuality is highly valued and encouraged. In such cases, we may well ask why any single sexual relationship would be valued by an individual in such highly permissive cultures. But we must not forget that in such societies, one's overall sexual life is considered very important - even though any one partner may not be thought of as essential. Because of the value placed upon sexuality any action that interfers with sexual activity by luring away a current, even though casual, partner might well arouse jealousy, for although the partner or partners may not be highly valued, the activity is. Such cultures also value marital relationships, and thus sexual relations in marriage would be given boundaries even though in sexually permissive societies those boundaries might be somewhat more fluid and allow for other sexual partners under more conditions.

In order to examine the evidence further, let us look at one of the most sexually permissive cultures, the Marquesas on the eastern edge of Polynesia. We find Suggs reporting thus: 13

Extramarital exploits are most carefully concealed in most cases, but news generally leaks out.... Extramarital relations, if discovered, usually arouse extreme manifestations of sexual jealousy (Tomakou) in the injured party. Wives who are known or suspected to have had extramarital relations are generally beaten by their husbands.... Women who suspect husbands of being unfaithful respond by adopting a behavior pattern in which they display moods of depression and/or shrewish irritability.... [One informant's wife] spent a day sobbing intermittently, saying that he no longer loved her.... Since then [ordered him] ... to leave the house ... and go to the other woman. (Suggs, 1971: pp. 119-120)

Similarly, in northern Australia in the highly sexually permissive Goulbourn Island area studied by the Berndts, we find reports of how a husband reacted when he discovered his wife having coitus with another man: 14

The husband suspecting that his wife was having a liaison, had followed her tracks and eventually, hidden behind a clump of bushes, observed the two of them copulating. And he said to himself, "This woman doesn't like me; she likes him better than me." (Berndt and Berndt, 195 1: p. 202)

Thus, it seems certain that there are in these highly sexually permissive cultures marital sexual relationships that are felt to be important and inviolate. This is so even though the emphasis and meaning of love in these societies varies a great deal from that of the Western world.

Another interesting area to examine is polygamy, that is, kinship systems wherein there are multiple mates of at least one gender. Here, one might reason that since it is acceptable to have multiple mates, then sexual jealousy must have been eliminated within the marriage. To check this expectation let us examine the operation of polygyny, by far the most common form of polygamy." 15 Polygyny is the marriage of one man with more than one woman.

The usual way of avoiding overall jealousy among multiple wives of the man is to invoke some clear distinction among the several wives. This can be done by making the first wife dominant over the others and by giving her veto power in the choice of additional wives. Furthermore, new wives, especially if they are not sisters, are most often housed in separate huts with their respective children. In addition, the rules of polygyny usually set down routinization of sequential visits to the various wives so that an unaccepted sexual focus on one wife will be avoided. To illustrate, in many such polygynous systems, if a husband slept two nights in a row with one wife, he would have seriously breached the norms of marital sexuality.

So, even in societies with legitimate multiple mates, there is awareness of the difficulty of avoiding sexual jealousy and fixed sexual sequences are often normative. Even in imperial China the emperor was restricted to a fixed order of sexual relations with his various wives. 16 In the Near East, the historical accounts regarding the wives of Muhammad indicate the clear presence of jealousy. A search through Greek, Roman, and other civilizations reveals the same full awareness of marital sexual jealousy and the presence of a set of customs dealing with its management. The power of sexuality to evoke jealousy is easy to demonstrate historically as well as cross-culturally in polygynous as well as monogamous marriages.

The connection of jealousy to polygyny is made more apparent by the fact that in Africa and elsewhere the word for polygyny and jealousy is often the same. Schapera mentions this in his book on the Kgatla section of the Tswana tribe among the Bantu in Africa:17

The word lefufa, whose primary meaning is "jealousy", is also used for "polygamy", an extension that Kgatla explain by pointing out how seldom it is that co-wives can live together amicably! (Schapera, 1941: pp. 279-280)

Our examination of polygyny reveals that jealousy customs operate in ways that may minimize negative emotions among the kin and friends of married people. The married individuals are intimately related to other marital units through various kinship ties (parents, children, clan members, and so forth), and these relations can easily be disturbed by unsanctioned sexual relationships. This does not mean that jealousy is used as a reason to stop all such extramarital relationships; rather, it tends to restrict those additional relationships that are thought to be disruptive of kinship and friendship ties.

My assertion of the universality of marital sexual jealousy contradicts the popular relativistic view of all customs which usually contends that "it all depends on the society." Such a perspective implies the existence of cultures where marital sexual jealousy does not occur. If this were so, then my notion of the universal linkage of sexual jealousy to marriage would be in error. Thus, it is strategic to examine now two cultures where it has been claimed jealousy does not exist.

One of the cultures that some have claimed lacks jealousy is the Lepcha in the Himalayan Mountains, studied by Geoffrey Gorer. Gorer reported that the Lepcha language has no specific word for jealousy. Some observers took the lack of a word for jealousy as evidence that marital sexual jealousy does not exist. But I believe the account by Gorer indicates that jealousy situations are recognized and are emotionally disturbing, although seemingly less so than in the majority of cultures. To examine this point, let me quote Gorer:18

When I presented hypothetical jealous situations to Lepchas and asked them what their feelings would be, the greater number say they would be angry; but this word, sak-lyak, does not carry very strong emotional connotations; it is the word used by parents if their children are naughty, or by workmen if they come across an unexpected difficulty in their work.... [Nevertheless,] married women who show marked preference even for perfectly hereditable spouses, and married men who show preference for women other than their wives produce and have produced many disquieting situations, sometimes leading to open disputes and even suicide. (Gorer, 1967: pp. 162-163)

So, even in this very unusual culture with its high degree of sharing and its strong norms against aggression and its direct teachings against jealous reactions, we still find that the jealous reaction makes sense to them, although it is controlled and in part minimized. One control on the emotion of jealousy is the Lepcha norm that extramarital affairs should be kept casual and emotionally unimportant to the person involved. In effect, this norm defines one aspect of the protective boundary this culture places around marital sexuality. This restriction reflects the desire that marriage have first priority, and this is so despite the fact that the Upchas do not have a very romantic view of marriage.

In addition, in the Lepcha marriage ceremony the woman is told, "If you had any other lovers you must leave them" (p. 336). When you interpret this demand together with the Lepchas' admission of reacting negatively when their mate gets involved sexually with others, and their norms regarding a low priority for extramarital partners, then it does seem that we have additional evidence for the existence of normative sexual jealousy boundaries in Lepcha marriage.

But what about the fact that the Upcha lack a word for jealousy? That lack does not necessarily mean they are unaware of that emotion or have no norms concerning jealousy, but rather it may indicate that culturally they are trying to contain jealousy. A comparable situation prevails in Tahiti.19 There is no Tahitian word for deep feelings or emotions. The Tahitians know about such emotions but they want very much to control them, and so their language reflects this desire in its avoidance of that concept.

On this point, I should mention that the Lepcha have no word for puberty, either. They surely recognize the growth of breasts, pubic hair, and musculature but do not stress this period, and so they have no separate term for the entire complex of changes associated with puberty. They view puberty as a natural consequence of having intercourse as a child and do not give puberty any separate existence.

Lack of a term, then, does not mean lack of recognition; it may simply mean a lack of stress on what that term represents. In fact, in some cases, the lack of a term implies that the custom is so obvious, no special word is needed. What is essential is the search for whether the behavior and belief pattern that a word represents is present. Then one may search also for the presence of special words to represent that pattern. As one interesting illustration, I would cite the fact that the San Blas culture in Spain has no word comparable to our term macho.20 Yet the San Blas culture is often cited as an ideal example of a culture with macho male beliefs and behavior patterns.

Finally, I should mention our own hesitancy when we speak to small children to use explicit words for genitalia or for sexual acts. American parents often say "Don't touch it" or "Don't do that" when referring to sexuality. This is another example of how a lack of explicit terms does not mean that a group has no customs concerning that area of behavior. Rather, the very hesitancy to be explicit in an area may be an obvious expression of strong normative beliefs concerning the desire to control that aspect of behavior.

Some of the Eskimo groups comprise a second type of society that has been cited as lacking marital sexual jealousy. Traditionally some Eskimo societies have had the custom of sharing mates with others such as guests or friends. To conclude from this that marital sexual jealousy is absent, however, confuses the act of accepting one type of extramarital arrangement with the act of accepting all types of extramarital arrangements. O'Kelly makes this point in a review of Eskimo sexuality: 21

Extramarital sexuality is a source of great jealousy among the Eskimo and both wives and husbands are quick to suspect their spouses. However, this jealousy exists alongside the practice of sharing or swapping spouses which requires the mutual approval of all participating parties and serves to establish close kinshiplike ties among the non-kin involved. (O'Kelly, 1980: p. 97)

After examining these and other societies, I would contend that no culture is indifferent to sexual jealousy in marriage-not even a culture with a very high degree of sexual freedom such as the Lepcha or some of the Eskimo societies. Of course, this conclusion is subject to further empirical testing, but for the theoretical reasons I have already stated, I doubt if any society will be found totally lacking in marital sexual jealousy.

IS MARITAL SEXUALITY SPECIAL?

In order to further explain my perspective on marital sexual jealousy I will have to speak a bit about the institutions of marriage and the family. These are our basic kinship institutions. It is the linkage with these institutions that joins sexuality with kinship. I developed some of my thinking here in the preceding chapter. There I emphasized the power of sexuality with its physical pleasure and self disclosure characteristics to bond people together into stable relationships and I stressed this as the basis for the importance given to sexuality. Many of these stable relationships will be heterosexual and the female will become pregnant. This leads to kinship systems composed of marriage and family relationships and as a result reproduction then takes on importance.

All peoples regardless of their biological knowledge of reproduction are aware that the birth canal of the infant is the same area used in sexual intercourse. Even if a society does not believe that intercourse is the main cause of pregnancy, it will usually assert that males have a role in pregnancy. So there is an association of sexuality with pregnancy but this is not the same as saying that all peoples see a biological causal connection of sexuality to pregnancy, such as we do. In the preceding chapter we discussed some non-biological ways that in which the male role in reproduction is perceived, and therefore I will not repeat them here.

The female contribution to reproduction is considered obvious in all societies. However, there are great differences as to what the female contributes to the offspring besides her womb. In Western history it was the Greek philosopher Aristotle whose beliefs were the most influential. He viewed the male as supplying the semen and the female as providing the material for the semen to work upon: 22

If, then, the male stands for the effective and active, and the female, considered as female, for the passive, it follows that what the female would contribute to the semen of the male would not be semen but material for the semen to work upon. (McKeon, 1941: p. 676)

Aristotle's views were widely accepted until recent centuries. It was only at the end of the nineteenth century that we scientifically understood the operation of fertilization. Understanding the recency of our scientific knowledge should make it easier to grasp the widespread prevalence outside the west of unscientific views of fertilization.

Regardless of how people related sexuality to reproduction, peoples everywhere desired to set up some expected ways that their daughters and sons would become involved in the bearing and rearing of children. The resultant kinship structures comprise the marital and family institutions found in all societies.23 The key point here is that the linkage of sexual jealousy is more with the bonds related to the marital and family institutions than with the possible reproduction of children. Hupka's data on marital sexual jealousy shows no relationship between the emphasis a culture places on offspring and the occurrence of marital sexual jealousy.24 Any sexual act which threatens the marital bond will evoke jealousy. It is not essential that illegitimate pregnancy be involved for marital sexual jealousy to occur.

Exactly how much responsibility each parent will have for the ensuing children is more variable for the father. In matrilineal societies such as the Hopi Indian society in Arizona, or the Trobrianders near New Guinea, the man will spend much of his time with his sister's children. This is so because in such societies one traces their descent through the female line and therefore a man belongs to his mother's and sister's descent group while his wife and all their children belong to her mother's descent group. It is the man's duty to tend to the children in his lineage and that means his sister's children. Of course, this means that the man's wife will analogously have the assistance of her brother in the care and instruction of her children.

Regardless of the ways men and women are attached to children, in all these cases, specific arrangements are societally put forth as the expected way in which a woman will be attached to a man at the period of her life when she bears children. Sexuality symbolizes the bond between the man and woman more than it symbolizes fertilization. In this sense the ties of sexuality is to marital and family relationships more than to reproduction. It is this type of linkage of sexuality with kinship which produces the universal presence of marital sexual jealousy.

The specific types of unions which are the social context into which children are expected to be born spell out the precise nature of marriage and the family in that society.25 Note that there is no requirement for any legal marital ceremony. Most of the nonindustrialized societies do not have formal legal systems in any case. The transition to marriage may be marked by the simple eating of a meal together by the woman and man or it may be an elaborate ritual with a celebration lasting over a period of days. In some cases the couple do not even live together. This is the case for the matrilineal Nayar in India where the husband visits his wife in the evening but both mates live separately in their own mother's dwelling.26 Nevertheless, the obligations and bonds of marriage and the concomitant feelings of jealousy exist even in this type of kinship structure. But jealousy here is not tied to reproduction for in the traditional Nayar society the woman would have "secondary" husbands and lovers and most of her children would be fathered by such men. Nevertheless, it is not such reproduction by other men that produces jealousy but rather it is both sexual and non-sexual actions which display a lack of concern which are more likely to produce jealousy.

Beliefs that symbolize the association of marriage to reproduction are apparent in patrilineal societies, wherein descent is traced through the male line. Jack Goody and others have pointed out that marriage in a patrilineal society symbolizes that all the infants born from that woman's womb belong to the husband's descent line.27 In matrilineal descent systems, the mother's relatives are also interested in all the products of her womb, for children belong to the mother's descent group.28 Our society is bilateral and therefore traces descent through both the mother's and father's line and thus all the close relatives from both parental lines are concerned about the offspring produced by a marital couple.

The reader should note that it is marriage which is tied to reproduction here. The shared desire is to have children born into a marriage between two individuals who are socially tied to each other. Sexuality is involved only as it is conceptualized to have a role in this process and its key role is more as a sign of the couple's bond than a cause of pregnancy. In many societies extramarital relationships of some sort are allowed and all children born to the woman are legitimate. Relatedly, an unsanctioned extramarital lover would be seen as a threat to the marital bond and would produce jealousy regardless of whether or not pregnancy occurred. I want to emphasize that the association of sexuality and reproduction follows from the bonding power of sexuality. It is that bonding power which is one major foundation of the marital relationship into which children will be born. The jealousy norms of a society protects the bonding potential of marital sexuality more than it does the risk of unwanted pregnancy. Such a pregnancy is but one of many potential threats to a marital relationships.

I fully believe that societies would strongly associate sexuality with marriage even if all reproduction were occurring in scientific laboratories with artificial wombs. Ask yourself: Would not husbands and wives still be jealous even in such a situation? Are not sterile mates as jealous as fertile mates? Can you explain wive's sexual jealousy as due to fear of their husbands impregnating other women? Is there not jealousy in homosexual relationships? Is not the heart of jealousy in the bonds of the relationship and their meaning, more than in any reproductive outcome?

I began this section with the question is marital sexuality thought to be special? The answer is yes! Marriage is the most valued home of the sexual relationship. Sexuality has its importance due to its pleasure and disclosure characteristics and marriage has its importance due to its tie to reproduction and the related kinship system. The importance placed on marriage demands that rights in the key areas of sexuality be present in marriage. This union of sexuality and marriage is what marital sexual jealousy is protecting. Sexuality is felt to belong naturally in a valued relationship like marriage. This reasoning is universally present and universally understood. In this sense, the association of sexuality with reproduction is a result of the societal joining of two areas of importance. More significant than any biological connection to reproduction is the fact that sexuality in marriage takes on associations with other interpersonal qualities of that marital relationship. This is another quite important dimension in any explanation of marital sexual jealousy. I will elaborate upon this point in the next two sections.

LOVE IS NOT ENOUGH

In the Western world we think that the basis for the jealous response is the affectionate quality of the marital relationship. Many people still feel that the self disclosure involved in sexuality symbolizes the love relationship and therefore sexuality should not be shared with extramarital partners. However, romantic and affectionate marital sexual relationships are not the only "triggers" that set off the sexual jealousy responses around the world. Any act that symbolizes a "betrayal" of the marital relationship, that is, a lowering of marital priority, can evoke jealousy.

In many cultures power and prestige related to duty-based marriages underlie marital sexual jealousy even more so than affectionate ties. Outside the Western world and even in parts of Eastern Europe, the choice of a mate is more heavily determined by economic or kinship ties. Affectionate compatibility, though almost always considered a positive characteristics, is not of first importance. In such a "pragmatic" marriage a male may, despite his lack of love for his wife as a person, believe that his wife has flagrantly violated his legitimate power over her by having an extramarital sexual relationship. Though the wife in such a society has less power, she may feel that her husband owes her the respect and honor of abiding by whatever the norms are concerning extramarital relationships. In this sense she has a belief that she is entitled to control her husband's sexuality within the limits set by the society. Underlying this belief in the legitimacy of controlling a mate's sexuality is an affirmation of the power of the cultural norms that regulate marital sexuality. Each partner feels justified in requiring that his or her mate abide by the shared cultural norms concerning marital sexuality. Let me reiterate that such a mutually binding agreement does not necessarily imply that one is treating people as property, as the Marxist position asserts. Agreeing to abide by any set of societal norms entails having rights to control other people's behavior without any necessary implication about property rights in the other people involved.

In addition to norms that stress affection or obedience to power rules (duty) as the bases for feeling a "violation of boundaries," males and females may feel jealous because of a third reason, the pleasure value of sexuality. Sharing with someone else the sexual pleasure that one's mate desires for himself or herself is thus another basis for feeling the boundaries of that relationship have been violated. In some Polynesian societies, the pleasure value of sexuality is highly valued, and accordingly there are restrictions upon married people sharing that valued good with others.

In sum, the norms of all societies usually stress affection, duty, and pleasure as the three key reasons for marital sexual boundaries, but societies do differ considerably on the relative emphasis they place on these three factors. We stress the importance of love in marriage, but even in a loveless marriage, contracted for reasons of duty or pleasure, many Americans would want their mate to avoid extramarital partners. The importance of these three factors for the marital sexual jealousy norms of a society is good evidence for my assertion that the tie to reproduction is not the sole, or even the most important, reason for sexual jealousy in marriage. Rather, the particular value of sexual relationships in marriage is due heavily to the specific linkages in a society to the love, duty, and pleasure aspects of marriage.

INTRUSION AND EXCLUSION:

THE STRUCTURE OF JEALOUSY

In all societies, whether marriage is based on love, duty, or pleasure, there occurs a similar individual assessment of extramarital relationships. This assessment involves the relationship concepts of intrusion and exclusion. Awareness of this will highlight the boundary-marking nature of marital sexual jealousy. It is therefore worthwhile here to take a social psychological perspective concerning the participants' feelings about extramarital sexuality.

When I have discussed the experience of sexual jealousy with friends, one response has stood out above all others. The response entails the feeling of being excluded by the mate from an important personal aspect of the relationship.29 If one's mate flirts with another person, that action exludes the uninvolved person from this part of the mate's life and leads to the feeling of being neglected in favor of some new attraction. That feeling of exclusion also leads to the judgment that the established relationship has been devalued by the person flirting with a new partner.

The other side of exclusion by one's mate is the intrusion into the original relationship by the new sexual partner. This reduces the privacy feeling of the original relationship and, like exclusion, also leads to the feeling that the priority of the marital relationship has been thereby reduced.

The mate who is sexually involved with an unauthorized new person is making an implicit statement about the marital relationship. Such persons are asserting by their action that the existing martial relationship is not important enough for them to forego going off with an unauthorized lover. Now, it should be clear that we are speaking here only of culturally unallowed actions. As mentioned earlier, if in most cultures with the levirate a younger brother has an affair with his older brother's wife, that would not have the jealousy-provoking potential of an older brother having an affair with his younger brother's wife. The former affair is authorized; the latter is not.

It is important to note here that in most of the cultures about which I have been able to obtain information, even when there is acceptance of outside relationships, those relationships are pursued with delicacy and with concern for the feelings of the partners who are not involved. Accordingly, a younger brother will usually wait for his older brother to leave his home for a period of time before seeking a sexual encounter with his brother's wife. It is clear to the people involved that this is a more thoughtful and more caring way to carry on an extramarital relationship.

The potential exclusion and intrusion feelings are something that is taken into account by most of the norms that regulate extrarelationship actions. A comment by the Berndts in their study of Australian aborigines indicates the importance of discretion in this highly permissive society:30

Jealousy is a big factor in pre and extramarital relations; ... This is why most extramarital ... affairs are carried out surreptitiously, so that the husband or wife, as the case may be, does not lose face. (Berndt and Berndt, 1951: p. 51)

Of course, in love-based marriages, the precise meaning of the exclusion when a mate adds a new, unauthorized sexual partner is different than in a duty-based or pleasure-based marriage. But, as I shall soon illustrate, the same general principle of seeking to avoid an exclusionary and intrusive action that violates the boundaries of the relationship is present in all three types of marriages.

The sexual relationship with a new partner is often seen as a potential rival to the time and energy devoted to the uninvolved person or persons. There is widespread awareness that both the pleasure and self-disclosing aspects of sexuality can draw one away from an original relationship. Having disclosed oneself in a sexual context may encourage one to disclose more in other contexts. The awareness of this possibility is present even in cultures where the love aspects of sexuality are not stressed and serves to support my assertion of the universal recognition of the disclosure potentials of sexuality.

Perhaps of even more importance for understanding the feelings of exclusion and intrusion involved in sexual jealousy is that marital sexuality over time becomes associated with a network of nonsexual self-disclosing acts. Sexuality in a stable relationship can come to be associated with declarations of love, with affectionate touching, with revelations of need, with sharing of stressful experiences, with public approval, and with much more. Sexuality is a repetitive aspect of a marital relationship, and thus it can easily take on special symbolic meanings concerning that relationship. For this reason, the extramarital sexual act is usually not seen as an isolated action by a marriage partner. Rather, since the sexual act symbolizes a great deal of the emotional and intimate aspects of the marital relationship, when that sexual act is done with a new partner, it is often perceived as threatening the total meaning of the existing relationship.

In cultures where love in marriage is not encouraged, the sexual act can still have much significance beyond the physical act. First, it is possible for affection to develop even when it is not culturally demanded. More importantly, in such cultures the act may well symbolize loyalty to the partner or obedience to the partner; or it may be a sign of the honor of their relationship, or even a symbol of reproduction connected to their children.

So, the Western romantic model is not the only one that leads to the association of marital sexuality with other important marital relationship aspects. The very importance of the sexual act in all societies guarantees that sexuality will integrate with other key relationship values - whatever they might be. This can be seen in our own society in the repeated findings affirming the close integration of sexual satisfaction with general marital satisfaction.31

In many different cultures the sharing of the sexual act by a married person with someone not culturally sanctioned is analogous to the revelation of a shared confidence to an outsider. No doubt this is part of the intrusive feelings about extramarital relationships. As we have discussed, sexuality has a private meaning to the couple; it is a meaning composed of a mixture of affection, duty, and pleasure. A married couple's sexual act takes on the overall meaning of the relationship and becomes a personal act symbolizing the nature of that relationship. To share that symbolic sexual act with an unauthorized outsider is often felt to devalue the special quality of the marital relationship. In this sense, the sharing of sexuality is similar to the sharing of a confidence that was given by one's partner with the expectation that it was something special belonging only to their relationship.

Schapera, in his study of the Bantu in Southern Africa, affords us some of this confidential aspect of marital sexuality:32

When our men keep going out at night we feel very jealous, because they make these other women know the insides of our homes and all the secrets of our lives. (Schapera, 1941: p. 207)

Many societies that accept extramarital partners recognize what we have discussed here and make a special effort to encourage people to compartmentalize or separate marital sexuality from the permitted extramarital sexuality. In that way the extramarital sexuality is kept from being intrusive upon the marital relationship. That such intrusiveness is so commonly felt in cultures around the world is evidence in support of the boundary mechanism view of jealousy. Only if one accepts a boundary about a marital relationship can another relationship intrude, for to intrude means to violate an existing boundary.

THE ACCEPTANCE OF EXTRAMARITAL PARTNERS

Regardless of the importance of dyadic boundaries it is crucial that we be aware that such extra partners can be legitimized. This point appears to have been overlooked by Pines and Aronson in their study of jealousy in a small California commune.33 They argue that Kerista Village in California has eliminated jealousy by its communal style of living involving 17 people. They stress that the 15 adults do not get jealous when sexual partners are rotated. However, they do report jealousy reactions if any of the members have sexual interests in "outsiders." This situation simply represents a change in boundaries from a dyad - normal for the West - to a somewhat larger group. Clearly, boundaries are still there, for sexual jealousy does occur when outsiders are involved.

Cross-culturally we can observe in polygyny a similar type of acceptable boundary that exceeds the dyad. In polygyny the husband and his wives comprise the group boundary that sexual jealousy norms surround. Surely, as we have discussed, even jealousy among cowives is quite common. In a sense the husband's relationship with each wife is a "separate" marriage, and thus some tendency toward jealousy would be expected. But as we noted earlier, this jealous reaction is considered inappropriate in polygyny and is blocked by various structural arrangements that attempt to order the interactions among the various wives with the husband. However, if a polygynist husband has sexual intercourse with a woman to whom he is not married and who is not approved of by the society, then the sexual jealousy response by his wives and their families would be much stronger.

I have mentioned that it is common in Polynesia and most of the nonindustrialized world to allow extramarital coitus for a younger brother with an older brother's wife. In a culture with this levirate custom, the younger brother will marry his older brother's wife if his older brother dies. The levirate tradition existed among the ancient Hebrews also. The sin of Onan mentioned in the Old Testament was that he did not impregnate his deceased older brother's wife.34 Instead, Onan "spilt his seed upon the ground." The offense to Hebrew society was not as many have supposed, that Onan masturbated or practiced coitus interruptus; it was, rather, that he did not fulfill his duty to his deceased older brother to produce children for his brother's line of descent.

In most levirate systems the legitimate sexual boundary extends beyond the simple dyad. Therefore, the older brother will strive to avoid feeling jealous if his younger brother exercises his levirate rights. The reader knows that the older brother has no sexual rights in his younger brother's wife. Such older brother and younger brother's wife relationships are often viewed like parent-child relationships. This restriction on the older brother may be part of a system of avoiding conflict that could result from the older brother using his greater power to gain sexual access to his younger brother's wife. Once again, we have a limit placed on power by other values in the society. This realization will qualify the position on power that I propose later in this chapter.

Thus, we have many instances of societies wherein extradyadic and extramarital partners are accepted. But we are also made aware that such arrangements are delicately balanced. The question arises, just how might we classify the strategies societies have utilized to deal with the potentially conflicting desires for extramarital relations and for maintaining the priority of a particular marital relationship?35 I would classify the societies that have been studied regarding such extra-partner sexual customs as presenting three basic ways of handling the potential clash of a new sexual partner with an existing stable relationship. These alternative approaches can be called (1) avoidance, (2) segregation, and (3) integration. I will briefly discuss these in turn.

The first normative approach to extra partners is to instruct people to strive to avoid any new sexual relationships. This is the way the Western world has formally chosen for dealing with extramarital relationships. Formally, the West has proposed that people should avoid such relationships entirely. In actuality, the female has been the one restricted by our Western customs much more so than the male, for society's punishment for transgression of "avoidance" norms has been harsher on the female than the male. To illustrate, the Napoleonic Code allowed a husband to kill his wife and her lover if they were found together in bed by the husband. The wife in the reverse situation had no such right.

Outside the Western world in the Trobriand Islands, with its society's very open premarital sexual norms, the double standard still prevailed in extramarital sexuality. The offended Trobriand husband did at times physically attack his wife, while the wife did not take comparable actions against her husband.36 Clearly, then, the avoidance approach has been applied more to the woman than to the man both in and out of the Western world.37

Outside the Western world there are some interesting variations. Davenport's study of East Bay in Melanesia offers a rather interesting case dealing with premarital sexuality.38 In this society the premarital sexual avoidance strategy for males is to permit homosexual relationships for adolescent males but to avoid all premarital heterosexual relationships. Such a strategy could work in extramarital relationships if a society accepted the promotion of homosexual relationships as a way of avoiding such heterosexual relationships. There is a connection between premarital and extramarital avoidance, for many avoidance cultures believe in the potential disruptiveness of both premarital and extramarital sexual relationships upon a marriage. Such ideological tenets help support many types of restrictive sexual approaches in a society.

The second general approach to extramarital sexual partners is to segregate the extramarital relationship from the marital relationship. This tactic places the other relationship outside the life space of the uninvolved partner. One version of this has been the common way that Western males have been engaged in extramarital sexual relations. They have had prostitutes or mistresses or lovers who were not known to their mates. This segregation of the "extra" person is intended to make conflict less likely by lowering the social visibility of the other relationship.

A more modern and equalitarian version of the segregation approach occurs when both mates agree that an outside sexual relationship can occur for either of them but that it must be kept separate from the life space of both partners.39

Extramarital agreements usually include restrictions so that the marital relationship receives priority and the competitiveness of the outside relationship is kept within bounds.40

One of the most common segregated extramarital arrangements is found among those non-Western societies that have the levirate customs.41 In most but not all of those arrangements a married person can have sexual intercourse with a sister-in-law or brother-in-law in part because they are potential future mates. But, as I have emphasized, even these outside relations are expected to be conducted with concern for the priority of the spouse and with the proper amount of low social visibility.

The third societal approach is to integrate the extramarital sexual relationship into the existing marital relationship. In modern America this would be exemplified by a sexually open marriage agreement that specifies that each mate should know the new partner and be free to veto choices he or she did not like. Furthermore, the uninvolved mate might wish to be kept informed as to how the new relationship is progressing and to be able to interact with the new outside partner.

There are cultures, such as the Turu in Tanzania, the Bantu in South Africa, and the Marquesans in Polynesia, where such outside arrangements are not uncommon and where the outside male may have to pay the husband for the privilege of such an agreement.42 In the Marquesans males or females are sometimes added to the household for economic reasons and given limited sexual rights. Among the Turu the integration of the lover is sometimes quite explicit.43

During the period that an affair continues, the lovers give each other gifts and meet secretly when they can. The husband and his wife's lover become friendly to the extent of exchanging invitations to beer feasts and helping each other with housebuilding, cultivation and other cooperative labors. They may even lend livestock to each other. The mistress becomes friendly with her lover's wife, helps her to grind grain, and makes beer for her and the husband. (Schneider, 1971: p. 66)

Sometimes among the Turu the husband will not go along with the love affair of his wife. Such a wife has pressure she can exert:

A wife will throw her husband's double standard in his face by pointing out that he has a mistress though he forbids a lover to her. (Schneider, 1971: p. 66)

Even in such open cultures the emphasis on avoiding public displays of the outside relation is stressed and the priority of the marriage prevails. In that sense, some of these affairs might be better classified as halfway between the segregated and integrated approaches.

Each of the three basic alternative strategies to handle the additional person has its own costs and rewards. The avoidance approach involves a great deal of constraint, especially in a society where extramarital opportunity is common. Violation of the norms in an avoidance culture can lead to strong emotional reactions involving guilt, violence, and divorce as well as, of course, sexual jealousy. But there is in such a system the security of believing you are promoting a stable marriage by the attempt at self-control, and the complexities of extramarital arrangements are avoided.

Segregated agreements by American couples have been reported in many studies in recent years. Here, too, violations of whatever the agreed-upon standards are may occur, and that would be a serious strain on the marital relationship. Also, the very presence of an extramarital agreement adds complexity to the relationship, for time and commitment must be divided in ways that do not disturb the priority of the marriage. But this system has one advantage in that there will be discussion of what type of extramarital relationship is or is not acceptable to each mate. In this sense they have more awareness of what risks and rewards such affairs involve for their relationship. This may enable such couples to make more informed choices regarding extramarital behavior and thereby be less likely to offend their mate.

In America, the integrative alternative involving a fully sexually open marriage has very high failure rates.44 The ability to accept emotionally the specific knowledge of and acquaintance with the extramarital partner is not widespread here. One way this can be handled is if the original relationship is not very highly valued. This, in fact, is part of the Polynesian cultural approach. Levy talks of the Tahitians' attempt to control the degree to which they become emotionally dependent upon their mates .45 In part, this aids the carrying out of extramarital relationships. But it is equally true that if the original marriage does not involve very high mutual dependency, then the outside relation may more easily replace it. However, this may not occur if the people involved are not seeking highly dependent relationships in the first place.

What about trends in the Western world among the three basic cultural strategies for handling marital sexual jealousy? These three modes (avoidance, segregation, and integration) are closely related to the three major aspects of marriage that trigger sexual jealousy (love, duty, and pleasure). It seems to me that if we stress the love aspect of marriage, then we make the integration approach very difficult and encourage the avoidance or the segregation approach to extramarital relationships. This is so because love does encourage a focus upon one mate and that leads to the desire for sexual exclusivity. On the contrary, if we stress pleasure in marriage, then we make the avoidance approach less likely and the segregation and integration approaches more likely. The pursuit of pleasure, when not combined with love, does encourage seeking other partners in a more open fashion. Given these likely interrelations of extramarital strategies and marriage structures, toward what directions are we heading?

I would contend that we in the Western world have been moving toward an era of greater choice in sexual relations and relatedly a lower value on sexual exclusivity. There are many reasons for this, including the far greater sexual experience of our young people today and their higher education, which tends to make them more willing to entertain new alternatives.46 Another reason for less sexual exclusivity today concerns the more diffuse nurturance of youngsters today. Due to high divorce rates we have large proportions of our population who have more than two parents with whom they may identify. This can reduce the focus of attention on any single parent, and that, in turn, may reduce the focus of attention on any single adult love relationship.

On this very point, recall that there is in Polynesia a diffuse nurturing of children.47 Adoption is quite common, and being raised by more than just one's biological parents is the norm in much of Polynesia. Thus, perhaps the Polynesian reluctance to seek exclusive love relationships is integrated with that diffuse upbringing. The Polynesians speak of "sympathy" and "empathy" and "concern" for each other and avoid the more demanding meanings of "the one and only" romantic love notions. Relatedly, Polynesians have a strong sense of autonomy that is antithetical to the high dependency implied by romantic love. A few in the West have also argued for the advantages of "pure" sexuality, unfettered by the demands of love, but they are clearly in the minority. 48

Most importantly, we should not forget that diffusing affection will not necessarily reduce jealousy unless the duty and pleasure aspects of marital relationships are also controlled. This is so because duty and pleasure may also serve as a reason for jealousy norms. In this regard, I know of no marital relationship system in any society that has eliminated from marriage all three of the key characteristics of affection, duty, and pleasure. Upon reflection it seems that it would be a strange sexual relationship indeed, in or out of marriage, that would eliminate duty, pleasure, and affection! Why would one bother with such a relationship? It follows, then, that while there is ample room for change in the structure of marriage and sexual jealousy, there are also severe limits to the reduction of marital sexual jealousy.

I think that for reasons of stability and security most people in the West will continue to elect avoidance of extramarital affairs of any kind, although even they will perhaps discuss this choice more thoroughly than has been the case in the past. I do think the integrative approach is too difficult for most people to cope with - it involves too many constant decisions and adjustments to the changing partners and to the number of people involved. In a real sense, the integrative approach gives new meaning to Jefferson's famous quote, "Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty." The unpredictability of negative outcomes and the constancy of the awareness of the extra partner will discourage all but a small number from the integrative approach.

In social life, everything else being equal, the more complex the custom, the less likely it will be adopted. One interesting evidence of this is that no culture has group marriage (multiple mates of both genders) as a preferred form of marriage, and only a very few cultures even have it as a rare option. The reason is the complexity of relating several husbands and wives to each other in one marriage. If monogamy, polygyny, and polyandry have problems with jealousy, imagine what the problems would be in group marriage! The rarity of group marriage, then, does support my point concerning the appeal of the less complex lifestyle of avoidance.

The approach most likely to grow is the segregation approach, where couples may inform each other that an affair might occur, but it will be kept separate from day-to-day life and will not become competitive with the existing stable relationship. In a large volunteer sample analyzed by Blumstein and Schwartz, 15% of the married couples stated they had such an agreement. This percentage is likely higher than what a representative sample would show for America today, but the point is that such marriages are not extremely rare events. Blumstein and Schwartz also studied extradyadic agreements among cohabiting and homosexual couples as well as married couples. Here is how they sum up all those agreements: 49

An open relationship does not mean that anything goes.... We never interviewed a couple who did not describe some definite boundaries.... The most important rules provide emotional safeguards-for example, never seeing the same person twice, never giving out a phone number, never having sex in the couple's bed, or never with a mutual friend.... These rules remind the partners that their relationship comes first and anything else must take second place. (Blumstein and Schwartz, 1983: p. 289)

The segregation approach, like all approaches, still has to deal with sexual jealousy, but I believe there are more people who can handle jealousy in this less intrusive form of extramarital sexuality than could handle the demands of the integrative approach.

Nevertheless, the segregated approach is likely to remain for some time considerably less popular than the avoidance approach. Most people probably enjoy the security of the avoidance approach, despite its restrictions. Changes in important boundary protection customs take considerable time to develop on the individual or the cultural level. Premarital sexuality changes much more easily, for it does not involve risk to an established relationship but rather can be the basis for establishing a marital relationship. Changes in extramarital sexuality involve important marital and family boundaries in a more direct, confronting fashion, and thus change occurs much more slowly. Nonetheless, our boundaries are changing.

SEXUAL JEALOUSY OUTSIDE MARRIAGE

AND HETEROSEXUALITY

I have focused upon sexual jealousy in marriage, but I do believe that other forms of sexual relationships will also display the boundary mechanism of jealousy. In addition, I have focused here on heterosexual relationships in marriage and I realize this ignores the homosexual world, but for establishing universal linkages to kinship this was necessary. Nevertheless, the integration of sexual jealousy with important relationships is assumed to hold for homosexual as well as heterosexual relationships.

The recent work of Blumstein and Schwartz indicates that male homosexual relationships are the most likely to have extradyadic agreements, usually of the segregated type.50 Lesbian relationships are less likely to have such arrangements. However, both groups of homosexual couples were found to be more acceptant of agreements regarding outside sexuality than were married heterosexual couples. Cohabiting couples were also more acceptant of such relationships with others than were married couples. So, the strongest restrictions on sexual affairs outside the primary relationship does seem to occur among married couples. I would suggest that this is so because of the conjuncture of marital sexuality with complex kinship relationships that themselves promote stronger jealousy boundaries.

The abundant evidence of sexual jealousy in gay and particularly lesbian relationships supports my position that the reproduction connection of marital sexuality is not a necessary element in the production of marital sexual jealousy. The greater emphasis on sexual exclusivity by lesbians as compared to gays is best explained by gender-role training. Both gays and lesbians indicate, though, that the sexual relationship tends to symbolize the nature of the bond in the couple, and it takes conscious effort to modify that association. The gays' weaker emphasis on the sexual exclusivity aspect of stable relationships is congruent with the much higher change of partners in gay as compared to lesbian relationships. Such higher breakage fits with the notion of sexual jealousy as a protective boundary. In many cases gays resolve the question of sexual jealousy by removing sexuality from a long-term relationship.51 The need to eliminate sexuality in order to stabilize a relationship speaks to the importance of sexuality. Nevertheless, in such desexualized relationships jealousy in other areas is quite possible if the relationship is considered important. The same desexualization solution occurs in some heterosexual marriages, although it appears to be much more common in stable gay relationships than anywhere else.

MALE DOMINANCE AND JEALOUSY:

CROSS-CULTURAL EVIDENCE

Before leaving this chapter I want to use the Hupka data on 80 cultures in the Standard Sample to test one major explanation of cultural differences in marital sexual jealousy. This explanation asserts that the marital sexual jealousy of husbands will be greater in societies where males have more power. Marital sexual jealousy by wives will be greater in societies that are more equalitarian. The logic behind this is that sexuality is a valued element of society and thus the more powerful will have greater access and fewer restrictions concerning their sexuality. Consequently, the more powerful will also expect to be able to exercise their power to restrict the sexuality of others and will be jealous when that fails.

We briefly discussed the place of male power in jealousy earlier in this chapter. What I am proposing here is a modification of the orthodox Marxist view. I accept the importance of social power in sexual jealousy norms, but I conceptualize somewhat differently the way power operates. The Standard Sample and Hupka's data will help in testing out these explanations. Since the next chapter deals with the general issue of gender power and sexuality, this specific examination is preparatory for that exploration.

In order to check my proposed explanations, I used a technique of data analysis called path analysis. This book is not the place for a technical discussion of this approach, but I must briefly explain the process so the reader can understand the diagrams that are presented.52 Basically, this type of analysis allows one not only to examine which variables are related to which other variables but to further specify the order in which these variables interrelate. For example, I could have simply utilized multiple-regression techniques to observe the net effect of each of the several variables on jealousy. In that way I could tell whether these measures of male power were each independently correlated to jealousy. That surely is worthwhile. But I wanted to go one step further, and so I also sought to find out how these various predictors of jealousy related to each other. The resultant diagram is a causal diagram in that, going from left to right, it hypothesizes the earliest causes in the specific relationships and moves to the right to hypothesized later results. I believe these procedures will become quite clear as we examine the outcome of my analysis of predictors of sexual jealousy in husbands.

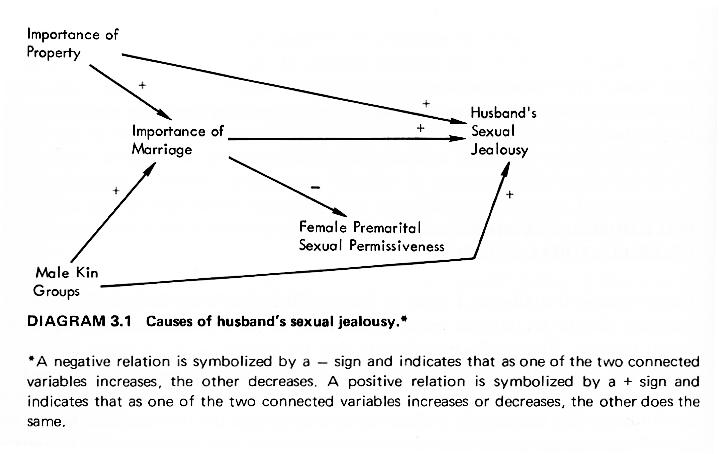

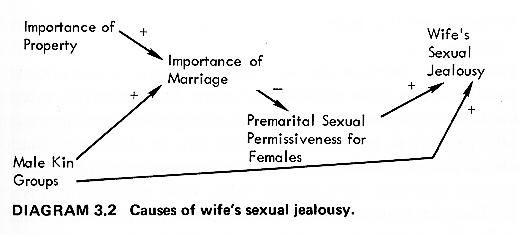

I present the basic causes of differences in husband's sexual jealousy in 80 societies of the Standard Sample in Diagram 3.1.

|

First, here is a brief explanation of each of the five variables in Diagram 3.1. The "importance of property" variable is a measure devised by Hupka. He measured the importance each culture placed on private ownership of property and the severity of punishment for theft of property. Hupka took this as a measure of how likely people would be to generalize to their mates their protective sentiments toward property and therefore more easily become jealous. I interpret this variable somewhat differently. I believe it is better used as a measure of male power. We know that males virtually everywhere control private property; thus, the greater the importance of property, the greater will be male power. It would therefore be the sense of power, not the particular source of power in property, that led to jealous reactions. This perspective better accounts for the jealousy of the majority of mates who have very little property.

The "male kin groups" variable was one I composed using two measures from the Standard Sample. Basically, it is a measure of whether a society traces descent through the male line (patrilineal) and whether males live together (patrilocal). My reasoning is that the more these customs are present, the greater the male ties to each other, and therefore males will be more powerful in that society.

The "importance of marriage" variable comes from Hupka and measures how much a culture's marital conceptions stresses marriage as necessary for survival and for being accepted as an adult. Hupka took this variable to predict jealousy because if marriage was important, then a mate would be more desirous of protecting the marriage against intruders. I use this as an indirect measure of male power. My reasoning is that if males are in power and wish to pass on their property and their group power to their offspring, they will stress the importance of marriage because that is the vehicle by which they can perpetuate their power in a society.

"Female premarital sexual permissiveness" is a variable contained in the Standard Sample. Hupka had used a general measure of sexual restrictiveness because he felt that there would be more jealousy if sexuality were restricted outside of marriage.53 I use this female measure for another reason: to see if greater male power produces restrictions on female premarital sexuality that might affect male jealousy.

The dependent or effect variable, that which we are trying to explain, is "husband's sexual jealousy." Hupka measured this by indexes of the severity of the response to an extramarital affair. This could range from a mild reaction to a requirement to kill the offenders.

Now let us examine the paths or lines connecting the variables in Diagram 3.1. First, the reader must be aware that the causal path lines that are drawn in the diagram are only those paths, of all possible paths, that came out statistically significant.54 In short, only the lines that an examination of the 80 cultures showed to be statistically important are included.

Starting with the variables that are the earliest in time, namely, those at the left of the diagram, we see that both the importance of property and male kin groups variables relate to the importance of marriage. The plus sign on each line indicates that the relation is positive or direct. Thus, as one variable increases, so does the other. In these specific cases it means that as the importance of property increases, so does the importance of marriage. Further, as the presence of male kin groups increases, so does the importance of marriage. Note that these two correlations support my idea that the importance of marriage is a reflection of male power as measured by these two other variables.

One might expect the importance of property and male kin groups measures to relate to each other, since they are both assumed to be measures of male power, but they are not significantly correlated to each other. This is indicated by the lack of a path (line) connecting them. Also, they are in the same column, which indicate that I am hypothesizing that they occur at the same point in time and therefore cannot cause each other. Many explanations may be tentatively put forth. First, it may well be that more than the importance placed on property promotes male kin groups. This makes sense when we realize that many hunting and gathering societies have very little in the way of property but are organized around male kin groups. This fact also qualifies the Marxist view of property notions being related to jealousy. We find jealousy in hunting and gathering societies, but we do not find much in the way of property.

Marxist writers and others have emphasized the role of agriculture in the development of male power. Were agriculture an important variable then it could be placed into the diagram as an early cause of both the importance of property and the presence of male kin groups. To examine this I introduced into the causal equation of Diagram 3.1 a variable measuring the degree to which agriculture was present in the society. I found that agriculture was not related to the importance of property, but it did modestly relate in a positive direction to the presence of male kin groups. This means that agriculture does promote patrilineal and patrilocal customs. Yet it does not directly relate to jealousy or any other variable. Thus, other factors, not detected by my search, must produce change in the importance of property in a society.

Let us follow the diagram further. The first three variables at the left of the diagram, just discussed, have a direct, positive relationship with husband's sexual jealousy. This is congruent with my expectations that the stronger these indexes of male power, the stronger would be husband's sexual jealousy.

Finally, the last causal path goes from the importance of marriage to female premarital sexual permissiveness. The relationship there is negative, meaning that as marriage becomes more important, female premarital sexual permissiveness becomes less acceptable. This is congruent with my expectation that male power would restrict female premarital sexuality as part of the effort to control sexual outcomes.