|

EROTICA

Pathway to Sexuality or Subordination?

PORNOGRAPHY OR EROTICA: WHAT YOU SEE IS WHAT YOU GET

EROTICA AND VIOLENCE: THE EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH EVIDENCE

EROTICA AND VIOLENCE: THE NONEXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH EVIDENCE

WHO GOES TO EROTIC FILMS?

EROTICA: A CROSS-CULTURAL VIEW

THE STANDARD SAMPLE: EXPLANATION OF RAPE

EROTIC FANTASIES AND GENDER ROLES

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

PORNOGRAPHY OR EROTICA:

WHAT YOU SEE IS WHAT YOU GET

The reader may think that now that we have dealt with homosexuality, we have handled the most controversial of areas. I do believe that, especially among intellectuals, the issue of erotica is more controversial. Intellectuals would very largely agree concerning the normality of homosexuality. They would be considerably more divided on the issue of erotica.

Even the choice of the term erotica as opposed to pornography is controversial, and so perhaps we should begin there. By now everyone must know that the word pornography comes from the Greek "pornograph" meaning stories about prostitutes. It has taken on a negative connotation over the centuries and today includes all materials involved with lustful ideas. The word obscenity is often used interchangeably with pornography, but it has a legal meaning. In American law the obscene is that part of pornography which has been judged to be illegal. To be so judged, the work must be offensive to community standards, appeal to prurient interests (lustful cravings), and lack serious scientific, educational, literary, political, or artistic value. The work must meet all three criteria to be declared obscene and therefore not protected by our First Amendment rights to free expression. This is one of the very few exceptions to the protection offered by the First Amendment to all expressions of ideas. Many court cases have tested whether a particular erotic movie or book is obscene by these criteria. Usually court decisions about obscenity are difficult to arrive at and are unclear.

In the 1970s some feminist groups began to formulate a distinction between pornography and erotica. They declared as pornographic those portrayals of women that they felt "subordinated" or "objectified" or "degraded" women in sexually explicit situations. They reserved the terms erotica for those sexually explicit portrayals they felt did not do these objectionable things to women. There is much controversy on this entire issue within the feminist movement. In 1979 Women Against Pornography (WAP) was formed, and this group has pushed for expanded legal restrictions on a wide variety of books and films they judged to be pornographic. In 1984 the Feminist Anti-Censorship Taskforce (FACT) was established in opposition to the position of WAP.

The distinction drawn by some feminists in the 1970s between pornography and erotica appeared to be simply a moral statement of their personal preference. Those who adopted such a distinction were in effect saying, "I like this type of sexual excitement, but I find this other type degrading." This is clearly not a scientific distinction. Technically speaking, the term erotica, from the Greek, refers to sexual love or sexual excitement. What is erotic to one person may be a matter of indifference or offense to another. It is our cultural training and our ideological beliefs relevant to sexuality that set up the sexual scripts that shape our erotic responses. The labeling of particular erotic scripts as "bad" or "pornographic" is a clear attempt to impose one's own sexual scripts upon others.

What is the most nonjudgmental term to use to describe the entire realm of sexually explicit materials in a society? To help make this selection, compare for a moment the term fornication with the term premarital intercourse, of the term adultery with the term extramarital intercourse. In both instances, the first term is a moralistic term with biblical origins while the second is an attempt to apply a descriptive, scientific term. I believe that pornography has become a negatively evaluated term much like fornication and adultery.

Therefore, I propose to call by the term erotica all materials that seem designed predominately for sexual arousal. The usage agrees with that of others such as William Fischer and Elizabeth Allgeier.1 Accordingly, the term erotica as used here simply refers to presentations that are sexually exciting to the typical audience at which the work is aimed. This usage also stresses the social nature of sexual excitement, that what may arouse and please one group of people may not arouse and may even displease another group. In this book all such materials shall be called erotica. If one dislikes a particular erotic form, that form can be called "bad" or "degrading" erotica. To label particular erotica as pornographic adds little to simply saying it is morally unacceptable to that viewer. Further, by having one overall term like erotica, we avoid building private sexual preferences into our terminology.

Much of the present controversy in America over erotica is a result of the chagrin and anger felt when others use what are felt to be "degrading" sexual stimuli for their sexual arousal. Of course, those using that stimuli may well not think of it as degrading, but they still are expressing a different choice of erotica. Such diverging erotic standards are part of the nature of a complex human society. We could find analogous sharp differences if we compared political beliefs or religious beliefs. Our morality enters into our judgment of all social activity, and surely sexuality is not excluded from that human tendency. The reader is, of course, free to find all erotica offensive or to find none of it bothersome. Our task here is not to judge what is moral but to explain how and, most importantly, why others arrive at their judgments.

Other uses of ideological beliefs in conceptions of erotica are quite obvious. There are those who would control a great deal of erotica because they feel people are usually influenced by it in a "harmful" direction; yet others feel that people are not so influenced by it and can intelligently choose here as they do elsewhere. Clearly, those two positions reflect our basic emotive and cognitive ideologies. In accord with these positions are pronouncements regarding what is "abnormal" or "normal" erotica. Epithets such as "sick" or "deranged" are frequently heard as accusations against those whose sexual scripts differ from their own. It should be clear at the outset that all Americans are in agreement in wanting to discourage those forms of erotica that are certain to lead to "harm" to others. The heart of the erotica debate centers on whether one believes that particular forms of erotica produce harm to others.

In a broad sense erotica would include anything that was designed to arouse us sexually. Nevertheless, our concern in this chapter is with a special type of erotica, namely, commercial erotica. More specifically, most of what I shall discuss concerns erotic movies - those rated X or beyond. A minority of such films contain obvious physical violence - like a sadistic rape or a brutal beating of a woman. A 1984 book by Robert Rimmer listed about 10% of the 650 films he examined as containing "deviational sadistic, violent and victimized sex."2 We shall have something to say about such films, but it is well to realize at the outset that they are not representative of X-rated films. As further evidence of this let me quote Dr. Thomas Radecki, chairperson of the National Coalition on Television Violence (NCTV): 3

NCTV has found the 1984 summer Hollywood movies to contain the highest amount of violence ever, 28.5 violent acts per hour, with PG movies containing some of the highest levels of violence. X-rated movies actually contain far fewer murders and even fewer rapes than PG or R-rated material. (Radecki, 1984: p. 43)

I will briefly describe a typical X-rated film. This is the type of film that is used in much of the research I shall discuss here. This film has a very thin plot, the acting is unimpressive, and the scenes focus upon oral, anal, and coital acts with extensive closeups of that action. The acts are mostly heterosexual, and when they are homosexual, unless the film is made specifically for male homosexuals, the focus is upon lesbian sexual acts. This avoidance of male homosexuality is due to the strong attempt to appeal to Western heterosexual males' lustful feelings in these films. Little or no physical violence against women occurs in the vast majority of these films. There may be some status differences in the male and female roles portrayed, but physical force rarely enters in obvious ways into the sexual action. I believe that this is the most common form of erotic film today. It is hardcore in that erections and vulvas are shown frequently and usually joined.4 We will discuss at length erotic films with violence, but the foregoing describes what the typical erotic theatergoer is exposed to.

EROTICA AND VIOLENCE:

THE EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH EVIDENCE

President Johnson set up the United States Commission on Obscenity and Pornography in the late 1960s. After two years of examining research evidence, this 19-person commission's majority report was that no harm was done by "pornography":5

If a case is to be made against "pornography" in 1970, it will have to be made on grounds other than demonstrated effects of a damaging personal or social nature. Empirical research designed to clarify the question has found no reliable evidence to date that exposure to explicit sexual materials plays a significant role in the causation of delinquent or criminal sexual behavior among youth or adults. (Report of the Effects Panel of the commission, 1971, p. 139)

Similar reports had been submitted by advisory commissions in other countries. Although Congress and President Nixon refused to change any laws, it seemed that the scientific question was at least temporarily resolved.

This temporary scientific resolution did not last long. Shortly after the ninevolume report of this commission we began to see the exploration of the connection between violent erotica and aggression against women. These new researchers pointed out that the commission had not sufficiently checked the differential impact of violent as opposed to nonviolent erotica, nor did they adequately explore the potential violent outcomes of viewing erotica. There had been earlier studies of the impact on children of violence on television, and that helped inspire further exploration of a possible connection between viewing erotic films and violence against women in society.

The new researchers were largely trained in psychology and used the experimental methods taught in that discipline. They obtained volunteer college males and placed them in a situation wherein a female confederate of the experimenter would anger these subjects. This could be done in a number of ways. One common method was to tell the subject that if he did a task a certain way, he would avoid an electrical shock and then to have the female confederate give the shock even when the subject did the task properly. Then with the subject angered, and therefore emotionally worked up, the researchers would show an erotic film. After the film the subject would be given an opportunity to administer a shock to the female confederate who had previously angered the subject. The students who were exposed to the erotic film were then compared to another group who had the same experience with the confederate but had not seen the film. The goal was to see if viewing the erotic film increased the likelihood of administering a shock to the female confederate. The results of these early experiments were inconclusive. Such inconclusiveness is not uncommon even today. Researchers in this area disagree a great deal as to the findings that are established. 6

Some experimenters thought that what was needed in order to discern the impact of the films was encouragement about giving shocks to the female confederate. They felt that perhaps the college male volunteers were on their good behavior for the experimenter. So, they verbally encouraged giving the shock, and in the experiment they offered the subjects a second chance to administer the shock. Still the differences between the control group (who did not see the erotic film) and the experimental group (who did see the erotic film) were not impressive.

Some of the early experiments in the 1970s indicated that softcore erotica, like Playboy, actually reduced the liklihood of an aggressive response.7 So the hardcore erotica was used in the newer experiments, and in some cases researchers then went a step further and showed erotic films with violence in them. In many cases this latter would be a rape scene in which the woman was beaten and raped. There was also the question of whether the dosage was too small, and so eventually massive doses of such films lasting up to several hours a day for several weeks were employed. With these alterations, the difference between the control and experimental groups was much more visible in many of the experiments.

Now, there were problems of determining just which of the several conditions of the experiment produced the increased willingness to give the shock. Donnerstein and Malamuth were two of the researchers who designed experiments to see if it was the erotica or the violence that was most important. They designed experiments in which one group saw a violent erotic film, a second saw a nonerotic violent film, a third saw an erotic, nonviolent film, and a fourth control group saw neither an erotic nor a violent film. The results indicated that erotic films by themselves without the presence of physical violence against women was not the factor producing the willingness to administer the shock. In point of fact, many of the films used by Donnerstein were not X-rated but rather were R-rated films seen on cable TV and in typical theaters. It seemed clear that the addition of physical violence to the film was the main causal factor. As Donnerstein put it:8

As we have seen ... it is the aggressive content of pornography that is the main contributor to violence against women. In fact, when we remove the sexual content from such films and just leave the aggressive aspect, we find a similar pattern of aggression and asocial attitudes. (Donnerstein, 1984: p. 79)

These results would seem to leave us with the view that if anything promotes violence, it is the viewing of violence. But life is not that simple. Zillmann has conducted some fascinating experiments that further qualify even this seemingly obvious conclusion. Zillmann compared the impact of erotica of various types and concluded that one major explanatory factor is the degree to which the viewer reacts pleasantly or unpleasantly to what is seen. He discovered that if the erotica - whatever type it was - was reacted to with a pleasant emotional state, then the likelihood of aggression was actually reduced. Whereas if the viewer reacted to erotica - whatever type it was - unpleasantly, then the likelihood of aggression was increased.

Thus, Zillmann suggests that it is not the objective content of the film that is important but the subjective emotional response to it. If one viewer is disgusted or frightened by a film, aggression is more likely. If another viewer is pleased and entertained by a film, aggression is reduced. Most strikingly we find that whether the film was erotic or not does not matter.

To test these ideas, Zillmann showed an eye-operation film that was assumed to lead to displeasure for most viewers and compared it with an erotic film featuring bestiality, which was also assumed to be unpleasant to most viewers. He found no difference in the aggression produced! Then he showed a film with scenes from a rock concert, which he assumed would lead to a pleasant reaction, and compared it to explicit coital scenes, which he also assumed would be viewed as pleasant. Again he found that in both instances the viewers were low on aggression. He sums up his views by saying that: 9

Sexual drive evidently does not have a uniform effect on aggressive behavior, and the diversity of modifications that sexual stimulation can produce consequently cannot be accurately predicted from the mere fact of sexual stimulation. (Zillmann, 1984: p. 133)

In the light of Zillmann's work, conclusions on the impact of erotica need to be further specified. In addition to the qualifications of previous researchers concerning the importance of prior anger, the length of the exposure, the encouragement to aggression, and the presence of physical violence, we must add the hedonic value of the exposure to the viewer. The complexity of this situation points to the need to avoid glib conclusions about the violent outcomes of viewing erotica.

Besides searching for aggressive outcomes of erotica, some research has inquired about attitudinal consequences of erotica. Their aim was to discern if males become more "callous" or lacking in "respect" for women as a result of viewing erotica.10 These researchers used the same experimental procedures I described earlier, but instead of seeing if an electric shock was administered, the outcome they now looked for was a higher score on Don Mosher's "callousness" scale or a higher score on belief in "rape myths" as measured by Burt's scale.11

Zillmann reports that attitudinal effects of viewing erotica are still measurable three weeks after exposure. The increased callous attitudes toward women is measured by increased support for beliefs that women are useful mainly as sexual objects. It is interesting to note that Zillmann reports similar "callous" changes in female subjects' attitudes toward other females.12 Other changes were observed in less favorable attitudes regarding gender equality, less severe punishments recommended for rape, and perceptions that a wider range of sexual relations are commonly occuring in society.

Zillmann's experiments, which involved massive exposure over a six-week period, also found that over this time period males became less critical of erotic films and less in favor of legal proposals to restrict erotic films. The subjects also came to be "habituated" by the films; that is, they tended to react less strongly to the films as time went on. All this indicates that the films were changing the viewer's attitudes.

Let's pause for a moment now and evaluate the experimental findings on aggressive behavior and attitude changes related to erotic films. First, I would sum up by saying that the exact specification of conditions that might produce particular outcomes is of primary importance. The type of film (violent only, erotic and violent, or just erotic) makes a great deal of difference, as we have seen. Also, the individual's reactions hedonically to the film affects the outcomes. Secondly, there does seem to be a change in attitudes when individuals are exposed to massive amounts of even nonviolent erotica, but just how "real" are these changes in behavior and attitudes in the experiment? How lasting are they, and do they predict future aggressive behavior against females?

In order to start to answer these queries, we must tend to the question, how valid are the results of all these experiments? Let us start with the reports of attitude changes such as those by Zillmann. We must consider the possibility that volunteer college males would not be fully candid when asked about rape myths, callousness to women, and gender equality prior to being exposed to the erotica. They might at that early point in time hesitate to endorse the callous statements that portray women merely as sexual objects. Nevertheless, after being exposed week after week to erotic films by the experimenter, they may feel more willing to open up and reveal how they actually felt all along.

I am suggesting that it is possible that the attitude change measured before and after exposure is really a change in willingness to reveal. In addition, this willingness may increase because the subjects sense the support of the experimenters for just such revelations. These possibilities have yet to be resolved by any research work, and so we must reserve final judgment.

Let us examine the question of the permanency of such attitudinal changes. Just how deep and lasting are such changes? Zillmann did the longest follow-up to date, and that was just three weeks after the end of the experiment. He did find that the attitude changes were still measurable at that time, but he also recognized the need for longer-term follow-up. Nevertheless, there is some additional evidence on the fixity of these attitude changes.

Malamuth and Check reported on their debriefing procedures and results.13 Such debriefings are required by the federal government granting agencies because the researchers assert the possibility that these films can increase the subjects' aggression and increase their negative attitudes toward women. Thus, all subjects are supposed to be debriefed shortly after the experiments in order to return them to their original attitudinal state. Malamuth and Check used a short procedure for this purpose. They gave the subjects a one-page statement that informed them that the attitudes of women in the films they saw were not typical; that is, they were told that women are not as sexually receptive as these films portray, nor do they quickly become aroused when a male attempts to rape them. In addition, the experimenters spoke to the men briefly on this same point.

The unexpected finding is that after this simple debriefing, the significant differences in attitudes between the experimental and control groups relevant to women disappeared completely. Actually, the exposed males were even less callous in their final attitudes than men who were in the control group and had not been exposed to any erotica! Now how does one interpret such results? One can simply say that these very short debriefings are quite effective. An alternative explanation is that the altered attitudes were never deeply rooted. As I noted earlier, it is possible that attitude changes both during the experiments and afterward were encouraged by a desire to say what the subjects thought was wanted by the researchers. Whether this "experimenter effect" is applicable or not, however, it does seem that the attitude changes were not deeply rooted.

Just how much outside social interaction with males and females it would take to have the same neutralizing effect as the debriefing is unknown. But without strong support in their daily lives for their "now" callous attitudes, it surely would seem unlikely that any such new attitudes would prevail. These findings lead to the conclusion that with day-to-day support for callous attitudes the films would hardly matter and without that support they would not likely have any lasting impact. In short, the power and longevity of such attitude changes as have been observed is questionable.

Consider next the behavioral implications of this erotica research: Do such films lead to violent acts against women? By way of preface the reader should remember that most of the causal connection of the film and aggressive behavior toward the female confederate was attributed to the negatively evaluated violence in the film and not to the erotica. Other researchers, like Zillmann, would argue that erotica, even if not violent, could promote the same aggression, particularly if the film was perceived as unpleasant by the viewer. There are still others who believe that even if there is no physical violence, but if a power difference in favor of the male is portrayed, that will in itself promote physical aggression against women. We have little to support this view, and I mention it only to indicate that nonviolent erotica has not been given a clean bill of health by all researchers.

It is also well to keep in mind that some people define as violent any form of presentation that represents a sexual relationship in which the male has more prestige or power than his female partner. Such usage of the concept of violence is hardly scientific and is best guarded against. Its source is a moral condemnation of gender inequality and the consequent assignment of negative connotations to all that signifies such inequality. Of course, one may study the consequences of gender power inequality without calling such situations violent. This is precisely what we did in Chapter 4.

Overall, the experiments we have discussed have shown that under some conditions (surely not fully understood today) some types of erotica do lead a college student volunteer to give a shock to a female confederate who earlier had angered him. The question I am raising here is, what can we conclude from this concerning the likelihood of rape or other physical attacks against women? I believe it is a long jump in logic and in evidence from the experiments to any statement about what is likely to happen in the outside world. Allow me to elaborate.

The social setting in which the individuals who view erotica are embedded is an important datum. To judge the consequences of any activity, one must have some idea of what alternative activities would occur if this one did not happen. If, for example, a group of 18-year-old males were not to go to an X-rated film, what would they do? Would they be exposed to conversations and events that would promote a different set of gender and sexual attitudes? In short, whatever beliefs are held about women among a group of 18-year-old males would likely be expressed when these males got together. Such views might well be just as "crude" and "debasing" and "subordinating" of women as those that might be in some erotic films. Therefore, the judgment about the impact of erotic films needs to be informed by what would be the alternate outcome if such films were not seen.

The reader might well raise the issue as to what produces the basic values that reflect the desire to go to an erotic film or to talk bluntly about sexual experiences over a pitcher of beer. The basic values are outgrowths of the ways in which males and females relate in our society. I believe the pursuit of commercial erotica is simply one of the social scripts that exists for finding pathways to the altered state of sexual arousal. To be sure, for a few it may be a means of expressing dominance or aggressive fantasies against women. But I would argue that for the great majority of males who go to an erotic film, the motivation is physical pleasure.

Certainly the erotic script, like all scripts, will contain values that reflect whatever male dominance exists in our society, but that is a common element even in nonsexual scripts, and it is not that but rather the explicit erotic character of the film that is essential in attracting the viewer.14 Remember that the plots in such films are quite thin. The focus of such films is on genitalia, not on character development. We will talk more of this later, but in order to help answer the question of possible violent outcomes, let's now look at evidence from nonexperimental research.

EROTICA AND VIOLENCE:

THE NONEXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH EVIDENCE

Studies have been made that examine the experiences of sex offenders with erotica in their formative years. The Kinsey Institute published one such study some 20 years ago and found that sex offenders in jail actually had less exposure to erotica than did prisoners who were in jail for other offenses.15 The backgrounds of sex offenders revealed parents who were puritanical and narrow in their approach to sexuality. Consequently, these future sex offenders were less exposed to explicit erotica when they were growing up than were other youngsters.

More recent studies have found similar results when comparing those imprisoned for sex offenses with those imprisoned for other offenses. At the University of Minnesota, Professors David Ward and Candace Kruttschnitt in 1983 undertook a comparison study of three matched groups of males: (1) those in jail for sex offenses, (2) those in jail for other offenses, and (3) those not in jail. In 1984 I helped examine some of these data and found that those in jail for sex offenses had had no greater exposure to erotica than those in the other two matched groups. These results were presented by Kruttschmitt at a City Council hearing in Minneapolis in March 1984. One might question how representative Minnesota is of the nation, but as I indicated above, similar findings have been consistently reported from other researchers.

Specific studies of rapists have been made to see if they had been more exposed to erotica than other men. Most of these studies have not found any such difference. Gene Abel, a therapist who has dealt extensively with rapists, made a comparison of his own.16 He compared those rapists who had extensive exposure to erotica to those rapists who had little exposure to erotica. His goal was to see if those exposed the most to erotica would commit the most violent types of rape or rape more frequently. Abel's results indicated very little in the way of differences between these two groups of rapists.

I am not trying to imply that erotica is totally irrelevant to crimes of sexual violence. There are a few sex offenders who state that they obtained the idea for exactly how to commit a rape murder from some film or magazine. To be sure, these are very few in number; but they do occur. However, once more we must raise the question, what would have occurred had these males not encountered the erotic films or magazines that detailed the way a rape murder could be carried out? Did the erotica cause the violence, or was the person already violently inclined and therefore sought out the erotica? Without erotica would such men have never been violent against women?

What we do know is that there are individuals who claim that a film triggered their response. Recall that it was John Hinckley who said he was pushed in the direction of attempting to assassinate President Reagan by seeing the film Taxi Driver. Incidentally, this was not an X-rated film. Also, in 1983 the networks played the film The Deer Hunter (also not an X-rated movie), which described some violent events in Vietnam. In one scene a game of Russian roulette was being played with real bullets. Within a week after that film was shown on television, the press reported that over a dozen young teenage boys had died playing Russian roulette. There were millions who saw the film and did not react this way. Yet one could still assert that this film was one causal factor in the deaths of those boys.

The fact of the matter is that for a very small proportion of highly suggestive viewers, a wide range of films may trigger a violent reaction. I must quickly add that it is also quite likely, however, that for such people there will very often be other events that can trigger some tragic reaction. The choice confronting the public is the degree to which they want to stop all forms of communication that may trigger violence in a very few. In order to protect the First Amendment rights of free expression, the courts have ruled that only those forms of expression that have a "virtual certainty" of producing potential harm can be banned.17

Our culture has historically relatively strongly supported freedom of expression. Despite this fact, we have placed more restrictions in the area of sexuality than in almost any other form of expression. As I have noted earlier, Supreme Court decisions have stated that erotica that violates community standards can be banned if it has no serious value in other important parts of our life. In addition, in 1982 we joined many other Western countries in banning all forms of child erotica regardless of whether it could be shown to be legally obscene. This was done on the grounds that children do not have the ability to defend themselves legally against abuse that might occur in the creation of child erotica. So, we have typically come down hard on erotica. This is surely due, in part, to our conservative sexual heritage, which includes a view of sexuality as something dangerous and evil that must be controlled (recall tenet 3 of the nonequalitarian sexual ideology).

The question raised by the new legislative proposals on erotica is not whether we should remove some of the standard First Amendment rights from erotica - that we have already done in our Supreme Court rulings - but whether we should extend and increase these restrictions. This is a personal value choice for each of us to answer. The review of evidence in this chapter is relevant to such a decision.

If we are concerned with the possible promotion of violence, the evidence from erotica research and other sources indicates that if any type of mass media presentation can lead to violence, it is the direct portrayal of violence.18 Even the exact causal operation of this connection is in dispute. We know, though, that there is much more widespread viewing of violence against women and men on television in R- and PG-rated movies than in X-rated erotica. As I have documented earlier in this chapter, only a small segment of erotica contains any portrayal of physical violence matching that on television or in other movies. Furthermore, the audiences at erotic films are but a small percentage of those attending to other more widespread forms of mass media.

WHO GOES TO EROTIC FILMS?

As part of my examination of the issue of the impact of erotica, I analyzed national data concerning who attends X-rated movies. Since we are concerned with whether such movies encourage the subordination of women, it is important to find out if those who attend are more opposed to gender equality. NORC (the National Opinion Research Center) takes annual surveys of a representative group of Americans 18 and older every year. One of the questions NORC often asks in these surveys concerns attendance at an X-rated movie during the past year.

I was able to examine six national surveys done between 1973 and 1983. About one fifth of all the respondents said they went to an X-rated movie during the past year. There were, as expected, more males than females attending (25% of males versus 14% of females). Almost half of those who went were under 30, and almost all the others were under 60 years of age. About 60% were married. I divided the respondents into those with less than a high school education, those who were a high school graduate, and those with more than a high school education. For each of these three groups the respective percentages of those who went to an X-rated movie in the past year were 13, 20, and 24. So, a higher proportion of those with at least some college education went to an X-rated movie in the past year.

Then I compared those who went to an X-rated movie with those who did not in terms of several questions that measured gender equality. Table 7.1 has those precise questions and the response breakdown by whether the respondent attended an X-rated movie in the last year.

TABLE 7.1 Gender Equality and X-Rated-Movie Attendance

The percentage difference on all four questions is enough to be significant on statistical tests. This indicates, then, that those who do go to an X-rated movie are more, not less, gender-equal than those who do not go. I checked these results separately for each year, for males and females, and for each education level, and the differences remained significant in all these subgroup comparisons. This indicates that these results are not simply an outcome of an unusual year or just applicable for males or just applicable to college-educated people.

As a further indication of the type of people who attend an X-rated movie, I examined questions on abortion and found that 46% of those who went and 34% of those who did not go approved of abortion for a "women who wants it for any reason." This fits with other research indicating that more gender-equal individuals are accepting of a woman's right to have an abortion.19 On questions of erotica itself the people who went to an X-rated movie were more likely to believe that erotica provided information and less likely to say that sexual materials lead to a "breakdown of morals" or to rape, and they were more opposed to additional laws against erotica.

These data argue against the view that erotica leads to attitudes supporting the subordination of women. It surely seems that many people who go to X-rated movies do not view those movies as degrading to women. These people seem to be high on gender equality, and it is difficult to believe they would participate in and defend an activity they believed lowered the value placed on women.

Of course, the NORC surveys do not have information on exactly what X-rated movies these people attended, nor do my results preclude there being a minority of people who attend such movies who do lose respect for women. The data do show, however, that on the average the people who do not go to such movies are more likely to be gender-nonequal. This lack of equality is certainly not due to exposure to erotica.

It would seem that much of the support for the opposition to many commercial forms of erotica comes from people who also oppose gender equality. For them, this is a matter of preserving what they feel is the proper relation of the genders and the proper expression of sexuality. In addition to this conservative group we have a radical feminist group also supporting legal restrictions on commercial erotica. To this subgroup of feminists, their stand is a political matter of fighting against what they feel is a degrading portrayal of women. They seek support for what they define as gender equality. This surely is not a major goal for the conservatives.

The Indianapolis ordinance that was designed to restrict erotica was introduced in 1984 by Councilwoman Beulah Coughenour, a Republican and a leader in Indiana in the fight against ERA!20 The radical feminists and the conservatives who support such restrictive legislation have one goal in common: They seek legally to restrain the forms of commercial erotica that are allowed. Yet their reasons for doing this are strikingly different and opposed. Nowhere is the clash of ideologies in our country more obvious than on gender equality, and yet we have in such legislation a pragmatic coalition.

The radical feminist opposition to many forms of commercial erotica stems from the gender-based reasons I discussed earlier in this chapter. These women are acutely aware that many males value women only for the physical pleasure they can derive from them. For women who are seeking equality, this body-centered focus of men is a constant denigration of their self-worth. The body-centered focus ignores the many other contributions to society that women make. It is that narrow view of women which so angers the radical feminists.

In addition, radical feminists, despite their gender equality, were socialized into our traditional gender roles when they were growing up. That traditional exposure may well have made these women likely to value a stable, person-centered sexuality and devalue the more pleasure-centered varieties that erotica often emphasizes (tenet 2 again). This early socialization plus their gender equality values probably led to the attempt to separate the erotica they liked from that which they disliked and call the latter pornography. In time it has led some to support the Indianapolis type of ordinance which restrains a wide variety of erotica that is supposed to subordinate women. Even nude photos that focused upon one part of the female body were labeled exploitive and called pornographic and included in the erotica that the ordinance would restrain. Clearly, the goal is to formulate in law what to this segment of feminists is gender-equal erotica.

They assumed that anyone who could enjoy an erotic scene that they interpreted as subordinating women must not be a gender-equalitarian person. I believe they have misread the meaning of erotica to most men. In my judgment, the erotica focus for most men is not to degrade women but to obtain physical pleasure from viewing explicit sexual scenes. The NORC data showing that men who see X-rated movies are actually more gender-equal than those who do not would appear to support this conclusion.

Betty Friedan, the founder of the National Organization of Women has argued against restrictive legislation. She advises feminists: 21

Get off the pornography kick and face the real obscenity of poverty. No matter how repulsive we may find pornography, laws banning books or movies for sexually explicit content could be far more dangerous to women. The pornography issue is dividing the women's movement and giving the impression on college campuses that to be a feminist is to be against sex: (Friedan, 1985: p. 98)

Sexual restrictions on women has for millennium been seen as a way to "protect" women from the "degrading" influences of sexuality. Protective motives have been used to restrict female paid employment and access to birth Control.

Note that very little of the outcry against erotica refers to the degrading or devaluing or exploiting of males in erotica. After all, males are in erotic films, and if such activity is "dehumanizing" or "exploitive of the human body," then this would apply to them as well. But males are not mentioned because the attention is on gender inequality, and males are the group in power and thus are not felt to require help. As I see it, the radical feminists' opposition to erotica is not basically an opposition to open sexuality - they would accept that if it were placed in what they defined as an equalitarian context. It is at its roots an opposition to what they judge to be a nonequalitarian view of sexuality. But, as I have noted earlier, there is a real question as to the accuracy of their judgment regarding what is nonequalitarian erotica.

The traditionalists who also support the control of erotica come at this issue from an altogether different perspective. They oppose commercial erotica because they feel that the sexuality involved is offensive to decency and modesty, as they define those terms. They would speak out equally strongly against homosexuality in ways opposed by most of the radical feminists. They would also be more restrictive on abortion and more "profamily" on many issues that would sharply distinguish them from most feminists.

It is not the gender inequality that the conservatives oppose in commercial erotica but the open display of sexuality. If gender inequality were displayed in some nonsexual context, such as on questions about abortion, daycare, working mothers, or women priests, such conservatives would not feel any need to speak out. In fact, many of them would actively support nonequalitarian positions on such issues.

So, we have a union of conservatives, who oppose the open sexual display, and radical feminists, who oppose not the openness but the gender inequality, as they see it, in those sexual portrayals. There are not many other issues where these two groups would be allies. I expect their union to be brief, for on the fundamental issue of gender equality they are indeed poles apart. As one indication of this radical difference I note that in Suffolk County, New York the conservatives have taken the model of the Indianapolis anti-erotica legislation and revised it to reflect a profamily and antigay position .22

EROTICA: A CROSS-CULTURAL VIEW

It is time to get a broader perspective on erotica. To do that I will present an overview on the place of erotica in the subordination of women, whether that subordination entails physical violence or just social subordination.23 In Chapter 4 we discussed at length the issue of gender equality. I pointed out there how sociologists measure the relative power of men and women by looking at their roles and influences in the major settings of the family, economic, political, and religious institutions. If one is constantly exposed to women as subordinates in all these institutions in terms of the influence they wield, then it is easy to understand why even young children would perceive women as being less powerful.

To the extent that women move into more equal positions of power in these basic institutions, we can expect such perceptions of female subordination to alter. Our "significant others," that is, our close friends, kin, and lovers shape and reinforce our attitudes toward men and women.24 These individuals are exposed to the same daily view of females being low on power in virtually all our major institutions. There is thus systematic reinforcement of the relative power of each gender. Change is surely possible, but just being determined to change things without altering the social position of women in the major institutions would be largely illusory.

Now let us confront the question of the place of erotica in the subordination of women. Just how much influence on the subordination of women does erotica have? I believe the research we examined earlier in this chapter and our awareness of the institutional sources of power lead to the conclusion that erotica has very little influence on the subordination of women in society. Erotica, as we are speaking of it here, is largely a commercial enterprise. The aim of such erotica is not social stability nor social reform but sexual excitement in exchange for money. The customer, here as in all of out markets, can select from a variety of products. Almost all these products reflect felt demand, and if that demand does not materialize, the product will cease to be manufactured. In short, erotica largely mirrors the socialization of those who use it.

One can discern changes toward greater gender equality in erotic films over the past decade or two. Just as an illustration, shortly after the straight movie Nine to Five appeared, an erotic film called Eight to Four that parodied it was made. Both films followed the same story line of a male chauvinist boss in an office and of his eventually being put in his place by his female employees. This same sort of use of common popular themes can be seen in other hardcore erotica films, such as Urban Cowgirls modeled after Urban Cowboys. My point here is that erotic films reflect what is of interest to potential viewers much more than they shape the direction of that interest. Such films, then, are more accurately viewed as simply an echo of the society in which we live. That being the case, as our society has become more gender-equal, so have our erotic films.

Most of the direct sources of a group's power are in that group's specific institutional integration as reflected in employment positions and ties to political groups. The viewing of erotica can hardly be conceptualized as comparable in importance to such fundamental forces. It would be easy to think of many other noninstitutional activities that would likely display conventional gender-role attitudes with considerably more influence. One need only think of television and nonerotic films. Each of these occupies far more of our time than erotic films and each surely in its own way imparts a gender-nonequal message.

As a way of analyzing the relationship of erotica to gender equality, let us examine other societies to see what role erotica plays in shaping gender roles. Do we find that those societies with the most lenient attitudes toward erotica are those with the greatest degree of gender inequality?

Quite the contrary is the case in the West. Those societies like Sweden and Denmark that contain a wide array of erotica easily available are the most genderequal countries in the Western world. It would be much more difficult to obtain erotica in countries like Spain and Belgium, and those countries are much less gender equal. The data are not available for a more systematic, detailed check of all Western societies, but what we do know hardly evidences any causal impact of erotica at all. In fact, as cited earlier, contrary evidence indicates that restrictions on erotica are much more common in gender-nonequal societies. It is apparent that nonequalitarian countries do not need open erotica to maintain inequality, and gender-equal countries are not moved from their equality by the abundance of erotica. Quite frankly, erotica seems a rather impotent element in the social construction of gender.

One careful check of the relation of erotica to the subordination of women was done in Denmark by Berl Kutchinsky.25 Denmark opened up its laws on written erotica in 1967 and on visual erotica in 1969. Kutchinsky compared the rate of sex offenses between 1967 and 1973 and found there was no increase in rape. He did find an 85% reduction of sexual offenses against small children in Copenhagen during that six-year period. Other sex offenses remained stable. It is relevant to point out here that in West Germany a similar check was made after the law changed, and a 59% reduction in sex offenses against small children was found. Kutchinsky speculates that perhaps for child sex offenders, the easy availability of magazines portraying child sexuality lessened some offenders' felt need for abusing children. I will not pursue the implications of this because our focus here is upon sex offenses against adult women. In that regard, there was little change in such offenses that could be attributed to the opening up of the laws restricting erotica.26

Kutchinsky also reports that after 1969 the sales of erotic materials fell by two thirds. It seemed that the Danish public had been quickly satiated in their curiousity and most did not use commercial erotica to any great extent. Kutchinsky calls this the "banana boat syndrome." He is referring here to the rush to buy bananas in Denmark when they again became available after the Second World War. That also did not last very long.

We have another interesting case study in Japan. After the Second World War Japan intensified its laws on erotica to conform with what they thought the United States would approve. They wished to emulate us in technology and so wanted to maintain good relations by not offending us with their erotica. While our laws have liberalized in the past 40 years, the Japanese laws have not altered much and still ban visual display of pubic hair or adult genitals. But as long as this ban is technically observed, much more is allowed than would be true in the United States. In Japan, for example, nudity in mass magazines (but no public hair or genitalia) is common and public television shows are more sexually explicit.

The one characteristic that interests us most here is that in both film and novel in Japan there is a recurrent theme of bondage and rape .27 Abramson and Hayashi state:

Of particular note in Japanese pornography (film and novel) is the recurring theme of bondage and rape. Although Japanese movies are much less explicit than their American and European counterparts, the plot often involves the rape of a high school girl. This theme is also evident in the cheap erotic novels (with titles like Gang-raped Daughter) and sexual cartoons. In fact, one of the best ways to ensure the success of a Japanese adult film is to include the bondage and rape of a young woman. (Abramson and Hayashi, 1984; p. 178)

One might suspect that with that form of erotica so widespread, if erotica is causal, Japan would have a very high rape rate. In actual fact, Japan has one of the lowest rates of any industrialized country in the world .28 In Japan, as in all cultures, the messages sent out by erotica are mediated through the shared attitude structure of the people. In the case of Japan there is a strong socialized sense of responsibility, respect, and commitment. Relatedly, shame plays a powerful role in Japan. The Japanese view erotic rape and bondage films as a cathartic escape valve that provides vicarious satisfaction for unacceptable behavior.

One important lesson of the Japanese case is that the erotic is not a direct pathway to imitation. There is always a filtering system and counterinfluences. To be sure, the Japanese generally internalize more controls than do Americans, but that is not to say we have none. No people simply imitate what they see and hear. To illustrate, the Western world has amongst its citizens those who endorse a sadomasochistic sexual style with its extensive exposure to violence.29 Yet very little unwanted violence occurs among such people. This is so because almost all sadomasochists are seeking pleasure, even if the pathway is through pain. They interpret their sexual relations in those terms and avoid unwanted violence. They demonstrate that if we communicate with one another, we have customary ways of using our ability to evaluate and choose and thereby interpret and organize our experiences in ways that are compatible with our values. At times this thought seems to get lost in the erotica debate.

In nonindustrialized cultures little systematic information on erotica is available. However, one study on modesty by William Stephens is relevant here.30 The Presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography sponsored Stephens's study of cross-cultural information pertaining to "obscenity" and sexual modesty. He studied 92 nonindustrialized societies using the Human Relations Area Files.31 He found that peasant societies, more than tribal societies, were restrictive in terms of sexual modesty as indicated by the insistence on covering the body. These peasant societies also had the strictest codes regulating premarital and marital sexual conduct.

Stephens studied the telling of sexual jokes and obscene stories and reports:

The peoples who seem most preoccupied with sexual joking and obscenity are not those who appear to have the most to [release], but those who should have the least. They tend strongly to be the most sexually free, the least constrained by taboo and modesty rules. (Stephens, 1972: p. 8)

Stephens believes that the control of the older, tribal "immodesty" resulted from the increase in deference and patriarchy that occurred with the advent of agriculture. He believes that more democratic and gender-equal cultures have fewer restrictions on sexuality. Such a lack of sexual restrictiveness goes with more acceptance of a blunt, direct approach to sexuality. The case with which a people engage in sexuality does not seem to reduce their erotic focus nor their gender equality.32

Of greatest interest to us here is his finding that these highly permissive, immodest groups were usually gender-equal. In talking of these groups, he states that

In all [these] groups, however, the status of women appears to have been relatively high, and family relations fairly equalitarian. (Stephens, 1972: p. 15)

This is additional evidence of a lack of connection of acceptance of erotica with gender inequality. In fact, once again the evidence seems to indicate that tolerance of erotic variety goes with gender equality. Of course, erotica in these cultures will not be identical with our types of erotica. Nevertheless, their erotica does include genital focus, concentration on orgasm, blunt sexual jokes, attention to female body parts, and centering on physical pleasures. All this is also common in our erotica.

Violent forms of erotica are not mentioned by Stephens, but one can still ask about the association of open-erotica cultures with high rape rates. The evidence here is again negative for if we look at the cultures Stephens classifies as high on erotica, we find they are generally ranked low on rape rates.33 Once more what associations we do find cross-culturally show a connection of erotica with low violence and with gender equality. I do not interpret such findings as evidence that erotica is productive of gender equality. Rather, I think more gender-equal societies are less restrictive on female sexuality, and part of such acceptance of female sexuality is a greater willingness to openly enjoy erotic images of many sorts.

THE STANDARD SAMPLE:

EXPLANATION OF RAPE

Since the issues revolving around erotica do bring into question the possible relationship to rape, it is well to deal with rape more directly at this point. My comments should have indicated to the reader that I do not accord much causal power to erotica in producing rape or almost any other major societal outcome. But if I deny erotica a role in the production of rape, then what societal facts would I involve? In order to answer this question, I did examine the Standard Sample and search for social factors that could be tentatively viewed as causally related to the frequency of rape in a society.

I start with the proposition that regardless of the form or extent of erotica in a society, those groups with low power will be most easily abused. Thus, cultures in which women have the least power should be cultures in which rape is most common. I tested this basic proposition using the Standard Sample. Both Broude and Sanday coded societies for rape proneness. Broude was able to code 31 societies on frequency of rape, while Sanday coded 95 societies using a somewhat broader definition, which included the use of rape in ceremonies or as a threat against women.34

It is important to note at the outset that both of these researchers disagree with Susan Brownmiller's view of rape as a crucial weapon that men have universally used to intimidate women.35

Rape ... is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear. (Brownmiller, 1975: p. 5)

Both Broude and Sanday found about half their societies were low or absent on evidence of rape, and in many of the other societies it did not appear that rape was socially supported as a universal threat to intimidate women. Brownmiller overlooks the fact that males have always had strong kinship reasons to protect their daughters and wives from sexual violence by other men.36 For this reason there are strong pressures working against the use of rape as a means of female exploitation. A view of "all" men as rapists is more a politicization of this area of research than it is a scientific statement.

Sanday does report that both machismo and interpersonal violence were characteristics of societies that had high rates of rape.37 She concludes that these are two basic causes of rape. I examined her data together with those of other researchers and found that the causal nexus was more complex than that. I used another measure of violence in order to see if a particular way of coding that variable made a difference in the causal picture obtained. Marc Ross had gathered data on several measures of violence 38 I took four of his measures, which covered (1) the presence of local community conflict, (2) the commonness of physical force, (3) internal warfare, and (4) external warfare. Surprisingly, I found that none of these measures significantly correlated with the frequency of rape as measured by either Broude or Sanday.

I then further examined Sanday's measure of interpersonal violence and discovered that even it did not correlate with rape frequency as measured by Broude. Sanday's measure of violence showed a significant correlation only with her own measure of rape. These results made me feel that the seemingly obvious causal connection between the presence of violence in a culture and the presence of rape needed further exploration. Even if one accepts Sanday's measures as valid and rejects those of Broude and Ross, it still seems advisable to search for other, possibly more important, causes of rape given this questionable support for the violence measure. For those who favor the importance of violence, it would be well to refine the meaning and the measurement of violence.

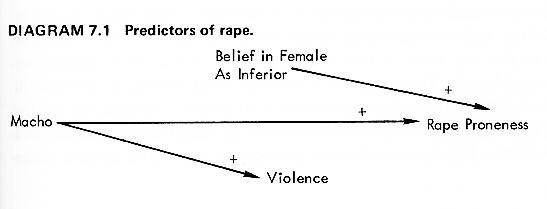

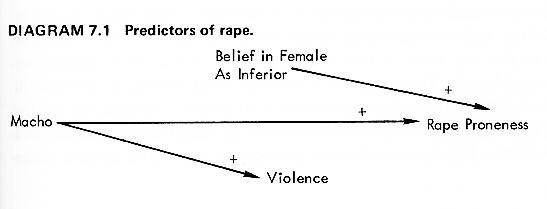

To search for other causal variables, I constructed and tested a causal diagram, like those I have used in Chapters 3, 4, and 6. This diagram analyzes the connections of two other causes in addition to the general violence in a culture. I wanted to see which of these three variables was the most influential on rape proneness when we remove any possible influence of the other variables. Causal diagrams answer precisely that question and contain only those variables that have their own "net" or "independent" influence .39 The results are in Diagram 7.1.

The statistical analysis showed that macho attitudes and belief in female inferiority influenced the occurrence of rape in a society.40 This finding is supportive

DIAGRAM 7.1 Predictors of rape.

|

of my position that the lower the status of females, the more likely they would be mistreated. The reader should realize that although the relationship of belief in female inferiority and rape is statistically significant, this does not mean that all groups with a belief in female inferiority will have high rape rates. It simply means there is a tendency in that direction-not a certainty.

Macho beliefs also appear as a somewhat powerful variable. It is a measure of the degree to which the male role endorses physical aggressiveness, high risk taking, and a casual attitude toward sexuality. The relationship to the belief in female inferiority did not quite make the required level of significance (see Appendix A, Table A.5). The relationship between these two variables in Diagram 4.1 was significant, although there we used Whyte's measure of machismo and here we are using Sanday's measure. It is possible, though that there is no causal relationship between these two variables and what correlation there is simply results from their both being products of a male-dominant culture. At the very least, given the findings in this diagram, we cannot be sure that macho beliefs themselves produce the belief in female inferiority. Macho beliefs in the diagram also shows a significant correlation with greater violence in a society. This seems reasonable given the aggressive element in such macho beliefs. Yet endorsement of aggression and casual sexuality need not imply endorsement of a belief in female inferiority. This is surely a point worth further investigation.

The diagram does not indicate any causal connection of violence with rape even though, as I have indicated, such a connection does shows up when using Sanday's measure of violence .41 The lack of support for this connection in the codes of other researchers makes this causal path questionable. Indeed, I would have thought that any culture that supported violence in other areas would support it in violence against women. It seems that this is not the full story, and perhaps particular beliefs relevant to the protection of females prevents this connection from being as common as one might think. The lack of a clear connection of violence customs with rape is one of the most surprising results of my cross-cultural analysis. I certainly hope that some of my readers will explore this area via additional research.

Surely a machismo view of the male gender may encourage men to view sexuality in an aggressive way. In this view, sexuality can be a way of getting back at someone. If the rapist did not conceive of sexuality this way, he would not use a sexual act to express his anger and power needs. One of the distinctive differences between rapists and other violent men is that rapists express their violence in sexual terms.42 There are also reports indicating a sexually restrictive upbringing of rapists, low empathic ability, and an aggressive macho-male conception. From a crosscultural perspective the key point is that the support for a machismo orientation rests on the power of male kin groups in a society. That power, as we saw in Chapter 4, is rooted, in part, in the kinship system. Our measure of male kin groups in Diagram 4.1 was the presence of patrilineal descent and patrilocal residence, and both are kinship terms. From a sociological perspective aggression derives more from group organization than from biology and thus male groups are important elements.

Of course, I am aware that there are many other variables that I could not consider, for they were not coded by anyone for the Standard Sample. Also, we need more precise ways to measure some key variables such as machismo.43 However, this analysis has shown that the variables in Diagram 7.1 are likely some of those central in producing rape. This affords the reader at least a beginning of the answer to the question of what produces violence against women.

EROTIC FANTASIES AND GENDER ROLES

One very important question that we must address here concerns the reasons why males and females in our society view erotica in such very different ways. If erotica is largely a reflection of our gender roles, then perhaps the answer lies somehow in that realm. Males do often seem to favor, or at least not to be offended by, the hardcore erotica. Females very often seem to be offended, particularly by hardcore erotica. Why this difference?

We might start by realizing that most erotica has historically been aimed at arousing males. Men have paid the money to purchase the books, films, and more recently video cassettes, and so the products have been aimed at their erotic satisfaction. That might help explain why women would be bored or indifferent to such erotica but not why some women would feel hostile toward such erotica.

To understand female hostility to male erotica we need to grasp the essence of the major theme of the majority of erotica. I believe that theme is a fantasy story of women who are sexually insatiable and are thus incapable of resisting any type of male sexual advance. Male erotic films show that in a matter of seconds, regardless of the approach of the male, the woman is overcome by her sexual passion and willingly participates in all sorts of sexual activities. Given a society in which males are trained to be the sexual initiators and in which males therefore often feel rejected by females who are not sexually interested in them, is it any wonder that this insatiable female fantasy would be so popular?

Erotica thus portrays women with their negotiating or bargaining power removed. In this sense it is analogous to rape, except that in rape that negotiating power is removed by the threat of the male, whereas in fantasy it is removed by the woman's raging sexual passions. Surely some women viewers resent this loss of choice in erotic films, especially when the scenario does not conform with their own notions of the proper way to promote erotic feelings. Allow me to elaborate on this point.

What is one of the most common female sexual experiences in our society? It is to be sexually pressured to cooperate with male sexual desire. Related to this, women know that males often want only their own sexual interests satisfied and value little else in their sexual partners. This makes women at times feel used and exploited and devalued. Many women deal with this situation by demanding affection before sexual performance in order to gain reassurance that they are valued in nonsexual as well as sexual ways. Such typical gender-role pressures also tend to make women more likely to view sexuality as an act of making oneself vulnerable to another person while at the same time making it likely that males will view sexuality as the taking of pleasure. Surely this sets the stage for potential conflict.

Given this common scenario in male-female sexual interaction, it is not surprising that women would be offended by much of erotica, for to be portrayed as having no bargaining power is to be helpless to resist a male advance that is unwanted. Erotic films also remind women of the male emphasis on body parts, and this may arouse whatever insecurities women have regarding the attractiveness of their own bodies. Perhaps this uncertainty about one's own body is part of the greater distrust of body-centered sexuality by females.44 The body-centered aspect of many erotic films may also remind some females that they are valued by many men only for their physical attractiveness. This narrow perspective may infuriate them when it is presented boldly on the screen.

Note that men are not so bothered when females concentrate upon male bodies. The reason is, I believe, that men know that they are valued in our society for much more than their bodies, and thus any emphasis on their bodies does not preclude other sources of self-worth. The situation for women is different, for although they are valued in other ways - as wives, daughters, and mothers - they are not as valued in the other major institutions that deal with power, like the political and economic institutions. Once again, the structure of one's gender role influences the reaction to erotica.

In a sense males and females are in a double bind - they want sexual pleasure in life, but they also want their sexual partner to value them as special. We have touched on this point in our discussion of jealousy in Chapter 3. Stressing the importance of selecting a sexual partner is one way for people to feel that they are special, but that very selectivity reduces the ease with which one can obtain sexual partners. Females in this bind are trained to strengthen their discretionary desires and concentrate on one man, and males are trained to strengthen the quick-pleasure aspect of that double bind and indulge. This gender difference is surely partly based on the dominant position of males, and it does create a different emphasis on sexual pleasure, or body-centered sexuality by males as compared to females.45

Women in particular are placed in a position where males are seeking to have sexual relationships with them, but these same males want their importance verified by the discretion exercised by their partner. Thus, women are pressured to be both very selective and very sexually responsive. Some of this same dual demand is placed on males by females, but with one important difference: In a male-dominant culture, the greater social censure for any violation of these desires will be visited upon women. Thus, women feel more constrained, and as a way of integrating their attitudes and behaviors, they are more likely to endorse a disapproving view of casual sexuality.

The conflicting objectives of selectivity and pleasure seeking are present in homosexual relations as well. Male homosexuals more strongly favor physical pleasure values while female homosexuals more strongly support selectivity values.46 In this sense homosexuals very much reflect the gender roles of the society in which they were reared.

If my thesis is correct and erotic fantasies reflect the desires that are part of one's gender role, for example, for males this would be wanting to be accepted as a sexual partner, then what about female erotic fantasies? The most common complaint heard from women is that current hardcore movie erotica does not have enough romance or plot or building up of a relationship prior to the sexual encounter. This complaint surely fits with the stress on commitment in the female role (recall tenet 2 of our nonequalitarian sexual ideology).

In one sense female erotic fantasy may be based on the same principle as male erotic fantasy. By this I mean that it is enhanced by removing the negotiating power of one's sexual partner. This is not done by making the male sexually insatiable but instead by making the male romantically obsessed.47 It is love or attraction of an intense personal sort which in this female fantasy renders the male helpless to resist. He must pursue her, give her what she desires, and treat her properly. The female sexual role is compatible with that scenario, and she can relax her sexual constraints and feel safe under those conditions. In this fashion, if the erotic film is romantic or at least shows that the male has a special interest in one particular female, then she can with little internal conflict project herself into the plot of the erotic story or film and allow herself to become aroused.

I am not arguing that love will not arouse males and raw erotica will not arouse females. We have experimental evidence indicating that males and females can be aroused by very similar scenarios. One recent study indicates that both genders are most aroused when the plot shows that the female initiates the sexual activity.48 This would be compatible with the male desire for a complying female and it would be compatible with the female desire not to be pressured into sexual activity. Females can be aroused by a pure erotic story providing that the female is seen as choosing to act sexually and is not being pressured in a distasteful way by the male just to satisfy his erotic needs. Likewise, males can be aroused by a romantic story if the male is not shown to be trapped in the relationship by the romantic feelings. So, if the social setting of the fantasy is congruent with one's gender role, then the basic turn on becomes the explicit sexual activity.49 But both genders fail to respond as easily when the setting violates their gender's sexual guidelines.

Our gender roles define power differences between males and females, and since sexuality is a valued goal, we have the potential for conflict among males and females concerning the achievement of this goal. Given the gender differences in power and the attractiveness of sexual pleasure, it is not at all surprising that dominance and submissiveness would be eroticized and expressed in our fantasies, although in different ways by males and females. Fantasies of power or submission seem quite common. One very important point here concerns the degree to which people make the distinction between erotic fantasy and reality. If that distinction is not made and the erotic fantasy is unacceptable as reality, the individual can be frightened. On the other hand, if fantasy and reality are distinguished, then one is aware that we can fantasize things we will never do in reality. The fantasy is thereby defused and its power to frighten removed. The Japanese's emphasis on rape fantasies and their ability to accept that as only a fantasy is a case in point, as is the reports by women of erotic forced-sexuality fantasies.

Males who have difficulty understanding why some women are not aroused by particular erotic themes might do well to speculate about what erotic themes would turn off men. For heterosexual males the answer would be to show them an erotic male homosexual film. In this instance, the heterosexual male viewer would be unwilling to project himself into this type of erotic scene, for he would feel that it is not the type of erotic turn on compatible with his male role. In any analogous fashion, much of hardcore erotica presents scenarios in violation of female sexual roles and makes identification with such fantasies difficult for many women.

If we do not seek to understand the societal reasons for the lack or presence of erotic response, we may easily attribute motives that are unrealistic. Some females may, for example, believe that the films that center on male sexual pleasure - even though usually lacking in physical violence - are expressions of male desires to subordinate women. We see some reflection of this female sensitivity to being exploited in the finding that wives, more than husbands, worry about oral sexuality being a service to the other person and wonder if they are being used.50

We think the meaning of oral sex is different for men and women. While many women may enjoy fellatio, others see it as a form of submissiveness, even degradation.... In cunnilingus, the male partner is not as likely to perceive the act as symbolizing sexual obedience, because he is apt to be the more powerful partner. (Blumstein and Schwartz, 1983: pp. 233-234)

Blumstein and Schwartz also make the point that lesbian women do not think of oral sexuality as involved with obedience or subjugation. This further indicates that those feelings are connected with the interface of male and female gender roles.

I would assert that there is a power element in erotica inherent in the desire to have the sexual partner do what would turn one on.51 But that is not the same as a desire to subordinate or to devalue either gender. The goal is to gain physical and psychic pleasure from a sexual relationship. To most viewers an erotic film is a fantasy way to enjoy themselves, not an expression of their disregard for the opposite gender.

Bearing on this same point, experiments that have been done on reactions to the use of force in a sexual film indicate that the great majority of men and women are turned off if the film portrays a woman who is being hurt and who shows clearly that she dislikes it.52 Despite that, both women and men respond with arousal to such a scene when the woman in a matter of a few seconds changes from opposition to total sexual surrender. The males who are the most aggressive prefer such "reversal" surrender scenes to consenting erotic scenes. For this minority of males, arousal is not blocked because of the opposition of the female partner. Again, given our somewhat macho male-gender roles, such a connection is not entirely surprising. I should add here that this connection arises from the basic macho type of gender role. It has been around a long time and is surely not a result of viewing an erotic film. In fact, it's social support was much stronger prior to the open erotica era of the last 20 years.

Sadomasochism is certainly relevant to an understanding of the relation of power to sexuality. Current research on sadists and masochists indicates that they typically do not seek to impose unwanted pain on each other. Most often they are involved in a mutually satisfying encounter. The masochist controls the sadist, and often there is a code word used which indicates the occasion when the masochist really wants the sadist to stop.53 To such individuals, subordination is the fantasy pathway for reaching sexual satisfaction, but subordination need not be a reality of their day-to-day relationships.

Sadomasochistic relationships illustrate how aggressive erotic actions can be utilized as erotic fantasy without leading to unwanted violence. This would support a perspective that stresses that people can distinguish fantasy from reality and that they can channel their desires for dominance and submission into sexual scripts that avoid unwanted violence.

This is not to deny that a small segment of both genders may resent the power over their sexual satisfaction that the culture bestows on the opposite gender. Males may resent that women can deny them their type of sexual gratification, and women may resent that males deny them the type of erotic scenario they seek. Most of us, however, negotiate our way through the intricacies of our gender roles and find sufficient satisfactions. A few may give up and begin to dislike and devalue the opposite gender, and perhaps many others have minor amounts of such feelings.