|

THE SOCIETAL LINKAGES OF HOMOSEXUALITY

PERSPECTIVES ON HOMOSEXUALITY: THE HETEROSEXUAL BIAS

A CROSS-CULTURAL OVERVIEW

NEW EXPLANATIONS: TWO PATHWAYS TO HOMOSEXUALITY

KINSHIP AND GENDER: STRUCTURAL SUPPORT FOR HETEROSEXUALITY

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

PERSPECTIVES ON HOMOSEXUALITY:

THE HETEROSEXUAL BIAS

I deliberately used premature ejaculation to open up the discussion of ideology and normality in the last chapter. Since premature ejaculation is not viewed as horrendous, I thought my ideas would obtain a fairer hearing than if I began with a more controversial sexual act. Let us now turn to a sexual act that seven of every ten adult Americans judge to be "always wrong".1 Is homosexuality an abnormal act? Remember, now, that I am not asking whether it is good or bad. That is a private moral judgment. Instead, I am asking whether there is a scientific concept of normality that homosexuality violates.

I spelled out my formulation of a sociological basis for a concept of psychological abnormality in the last chapter. If the characteristic in question would disable an individual from functioning in all societies, then I would apply the label abnormal to that characteristic. Psychological abnormality, in this view, is based upon the characteristic being universally socially destructive. According to this definition, as I will document in this chapter, homosexuality is not abnormal behavior. Of course, any sexual act, heterosexual or homosexual, can be used to express some personal abnormality, but nothing inherent in either homosexuality or heterosexuality is abnormal. In this section we will examine the belief put forth in various forms that heterosexuality is the normal sexual orientation, and anything else is therefore abnormal.

This is a sociological treatise, and thus the biological and psychological basis of what is being studied will not be tended to with as much care as will the societal foundations. My approach is not intended to imply that biological and psychological factors are causally irrelevant to the explanation of human sexuality. I surely do not believe that. My approach simply affirms my strong belief in the great value of a societal-level explanation of human sexuality. Of course, there are other causal factors that affect all aspects of our life but are outside of the purview of the sociologist. I will let others extoll the value of a biological or psychological approach to sexuality. In this book I deal with other approaches predominantly when they challenge or in other ways are relevant to the sociological view I am developing.

There are those who assert that if you do not support a biological causation view of homosexuality, you are exhibiting your prejudice against homosexuals. Such biological adherents reason that if homosexuality were conceived to be biologically caused, then people would not condemn homosexuals for they would know that homosexuals could not be changed in their sexual partner orientation. Two immediate responses need to be made to such assertions.

First - as a scientist one's interest is in discerning the causal nature of the situation, not whether the conclusions will lead to more or less societal prejudice. Of course, scientists are human beings and desire not to do harm to others, but their primary values as scientists assert that they must not distort or hide their findings. Some scientists might feel so strongly on an issue that they might refuse to publish their results and thereby place their private values above their professional scientific values. If a scientist distorted findings in order to promote a particular personal value, however, almost all other scientists would find that behavior totally unacceptable.

Accordingly, it would be scientifically unacceptable to assert that homosexuality is predominantly biologically caused when the evidence (to be discussed) does not support such a perspective. To be sure, those who politicize science might well condemn anyone who does not accept their causal viewpoint. As a scientist, I reject such politicizing of scientific work and reject pressures that condemn all but those results that one's private values support. That sort of approach leads to dogma, not knowledge. It makes research unnecessary, for the important answers come from ideological beliefs and not from careful scientific research.

One other point needs to be made about the current debate over the biological bases of homosexuality. I believe that those who dislike homosexuality will not change their feelings one iota if scientists were to assert that homosexuality is biologically caused. It is the homosexual activities and preferences that such people find objectionable, and that would remain the same. Analogously, we have had much racial prejudice in America, and surely whites are aware of the genetic basis of racial physical traits. Prejudice is generally based upon some conflict present in the lifestyles of different groups and not upon whether the causation is viewed as genetic. So, I would conclude that whether or not we accept a biological causation of homosexuality is irrelevant to the degree of prejudice that will exist toward homosexuality.2 If a scientific perspective is followed, then instead of morally judging all who disagree, scientists can spend their time investigating the empirical support for the various competing explanations of homosexual and heterosexual orientations.

Let us start our exploration of homosexuality with some definitions. I would define homosexual behavior as sexual behavior between two individuals of the same gender. Also, I would define a homosexual as someone who prefers sexual relations with a person of the same gender and whose erotic imagery is of the same gender.3 I use the gender and not the genetic sex of the individuals as the crucial distinction in homosexuality. We do not see the genetic sex of another person - we see their body type and their personality. Each culture selects from the genetic potential a set of physical and social characteristics and wraps the male and/or female genderrole label around them. It is the person's expression of gender and not their chromosomal makeup that may attract us sexually.

Note that there is a distinction between homosexual behavior and homosexual preference. One can engage in a homosexual act without preferring that act, just as one can engage in a heterosexual act without preferring that act. Also, one can have a cross- or same-gender preference without behaving in accord with that preference. A person may be heterosexual or homosexual in preference but abstain from all interpersonal sexual involvement.

The question of the normality of homosexuality is a universal question: Is there something that makes homosexuality in all societies evidence of some fundamental psychological problem in an individual that, like a broken leg, will prevent that individual from fully functioning in society? Some would hesitate even to search for an answer to this question, for they feel it implies that there is an abnormal personality type that goes with a homosexual orientation. This is certainly not my implication - the question of normality is raised because there are such strong ideological beliefs against viewing homosexuality as normal. Only by examining this question can we dispel, qualify, or confirm such beliefs. It is analogous to investigating the psychological implications of any individual orientation-like orthodox Christian, political democratic, or Marxist. We settle nothing by walking away from such investigations,

Let us examine some nonhuman species in order to gain a broader perspective on the question of homosexual orientation. In an examination of a wide range of nonhuman species of animals, R.H. Denniston concludes that4

in the vertebrates, apparent homosexual behavior increases as we ascend the taxonomic tree toward mammals.... Frequent homosexual activity has been described for all species of mammals of which careful observations have been made. (Denniston, 1980: pp. 28, 34)

The noted comparative psychologist Frank Beach reports that homosexual behavior is present in all species of primates on which studies have been made.5 It is clear, then, that homosexual behavior is far from a rare occurrence, especially in our cousins the nonhuman primates. The typical scenario for homosexual behavior in primates is for a male to assume the lordotic position in front of another male. This is called presenting behavior and involves putting the rear up in the air while bending over. The male bending over may well be mounted in such a situation.

In many instances these are acts of dominance and submission, not sexual acts. A defeated male may assume the lordotic position in front of the victor, and the mount by the victor may not have any obvious sexual elements. But in other cases we observe erection, anal penetration, and orgasm, which clearly is homosexual behavior, regardless of whether dominance is also present. Although less frequently reported, female homosexual behavior also is not uncommon in nonhuman primates.

The amount of homosexual behavior in nonhuman primates seems to be related to characteristics of the primates group. David Goldfoot and his colleagues report, for example, that when infant rhesus monkeys are raised only with other monkeys of the same genetic sex (called isosexual rearing), there occurs a notable increase in adult homosexual behavior.6

Both males and females in the isosexual condition were characterized by a partial inversion of the manifestation of protosexual behavior. Isosexual males showed statistically less foot-clasp mounting and more presenting than heterosexual males. Conversely, isosexually reared females showed statistically more mounting and less presenting than heterosexual females. (Goldfoot et al., 1984: p. 395)

Goldfoot notes that males showed greater effects of the isosexual rearing than did females. This study clearly supports the role of learning in nonhuman primate homosexual behavior.

The evidence on human homosexuality also shows its common occurrence. Kinsey and other researchers report that about a third of Western males have engaged in homosexual acts to orgasm.7 Most of these acts occur in the teenage years and involve mutual masturbation. The homosexual rates for females would be only about half or less of the male rates. We know much less about female homosexuals than male homosexuals both in America and cross-culturally.8 However, some recent sources of information on lesbian couples in America are available.

One key point here is that when we look at 20-year-olds, the percentage who prefer homosexuality is but a fraction of those who have experienced it. I would estimate homosexual preference in America between 5% and 10% of males and probably half that percentage for females.9 In this respect we are like the other primates, for they too have high proportions with homosexual behavior but rarely does this lead to homosexual preference.

The evidence of homosexuality as an almost universal occurrence in human and other species is so strong that no one can speak of homosexuality as an unusual or atypical act. Nevertheless, the common occurrence of an act does not establish its biological or psychological normality. However, if such common acts were destructive to group life, we should see evidence of that. I know of no such evidence for nonhuman primates. In further sections of this chapter I will show that homosexuality is an accepted element in a number of human societies and is there viewed as a behavior supportive of that society. First we need to examine some other areas related to the broad question of the normality of homosexuality.

If homosexuality is normal, why is heterosexuality universally preferred? In all species studied, very few individuals prefer homosexuality to heterosexuality, no matter how they were reared. Some psychiatrists and biologists have asserted that there is a "normal" biological basis for this preferential heterosexuality, and they generalize this assumed "natural heterosexual bias" to the human case as well.

I believe that is an unwarranted generalization. Nonhuman species are much more biologically controlled than we are. I have pointed out the impressive role of erotic imagery in human sexual behavior and showed how broad such preferences can be. One advantage of our larger frontal lobes is to afford us much greater imagination with which to plan our sexual lifestyles. Accordingly, it would seem that as you approach humankind, you find fewer biological controls on all parts of our social life.

As a sociologist I would start with the premise that in terms of orientation toward a sexual partner, humans are neutral at birth. That is, we have no genetic tendency to prefer someone of the same or the opposite gender. In fact, what the same or opposite gender looks like varies to some degree by culture. Cultures differ in their emphasis on thin or heavy body builds for both males and females; some cultures stress one type of hair, skin color, protruding buttocks (steatopygia), or particular genital size and texture. Therefore, humans could not have very precise genetically based preferences that would direct choice among such varieties of societal preferences.

Let us not forget the old "instinct" debates in the early decades of this century. It was Luther Lee Bernard, a sociologist, who in 1924 published his book on instinct and showed that over 14,000 human traits had been called instinctive.10 He insisted that any scientific use of the term instinct or any assertion about genetic influence must be tied to evidence concerning specific genetic mechanisms that could produce a particular outcome. If eye color is genetic, we can locate the specific mechanisms. Can we do this for sense of humor, for sexual interest, for heterosexuality? Bernard's advice is indeed an excellent guidepost to follow in the area of sexuality, where all kinds of views abound concerning what we biologically inherit.

For nonhuman primates the situation may be somewhat different. It may well be that sexual odors of the female attract the male, and the sexual swelling of the female genitalia at estrus may also function in such a fashion. The female estrus cycle leads to a time each month when she will be most sexually aroused. The human situation is quite different. We have little evidence of olfactory arousal or of any specific time period during which the female is more sexually aroused.11 Our sexual practices, erotic preferences, and courtship forms are much more varied than those in any other primate species. So, I would conclude that although there may be biological pressures which lead to heterosexual preferences in other primates, it does not follow that they are also operative in the human situation.

The argument over biological causation of homosexuality is an old one. Writing in 1896, Havelock Ellis referred to his acceptance of the biological perspective as a new approach.12

Some authorities who started with the old view that sexual inversion is exclusively or chiefly an acquired condition later adopted the more modern view. (Ellis, 1896/1954: p. 165)

The twentieth century once more reversed this judgment. Most researchers stress the importance of learning in the development of homosexuality. The evidence today establishes no clear basis to reject a largely learned view for homosexuality. In a review of the hormonal basis of homosexuality Garfield Tourney concluded: 13

The hormonal theory of sexual regulation, particularly in terms of orientation toward the sexual object, lacks evidence.... The hormones largely have their effect on end organ sensitivity while the libidinal urge or sexual drive may be largely psychological. (Tourney, 1980: pp. 41-42)

Further, in an examination of chromosomal differences in homosexuals, John Money concludes: 14

According to currently available evidence, the sex chromosomes do not directly determine or program psychosexual status as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual.... The hormones of puberty do not change the basic psychosexuality of a person. They simply activate and intensify it. (Money, 1980: p. 69)

The area of greatest speculation concerns possible prenatal effects on the human fetus that structure the brain in a fashion different than most fetuses of that genetic sex. We know very little about this in humans, however, and we have only speculations at present. I do not rule out such possibilities, but I feel that experiential causes, which we have seen do influence nonhuman primates, are even more important in the human case. We need not choose between a biological and a sociological explanation. Both viewpoints can produce explanatory theories.

I find biology, at least at this stage of its knowledge, to be largely mute on the question of why heterosexuality is preferred in human societies.15 The assumption of a heterosexual bias that operates in our human genetic makeup is gratuitous and only an article of faith. Of course, heterosexual choice is necessary for reproduction, but a population of bisexuals would reproduce very nicely. It is true that those who were fully heterosexual might produce more offspring, but if such heterosexuals were not biologically different from bisexuals or homosexuals, they would not pass on this heterosexual orientation to their offspring. We would be well advised to look outside our genetic inheritance and search for possible societal explanations of why heterosexuality is preferred. I will develop my own societal-level explanation further on in this chapter, but first let us look at another explanation of homosexuality that asserts that the normal progression for humans is toward heterosexuality.

The Freudian approach to homosexuality still is influential, particularly in the psychiatric community. I have previously indicated my rejection of the orthodox version of this approach and asserted that it was more a reflection of turn-of-the-century Western society than of any scientifically supportable perspective. The fourth tenet of the nonequalitarian sexual ideology basically asserts the same position in its required focus on heterosexual coitus (see Chapter 5). The wide-spread influence of Freud makes it necessary to examine his position.

Freud himself did not call homosexuality an "illness." In his now-famous letter to an American mother he said: 16

Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness, (Freud, 1921: p. 786)

However, Freud did refer to homosexuality as "perverse," and his followers seemed to view it as some sort of "abnormality." Part of the reason for this was Freud's assertion of the innate bisexuality of all humans. He viewed all of us as having the biological basis for going through a stage of homosexuality. This view rested in part upon embryological studies that show the remnants of the opposite genetic sex present in each infant. Freud reasoned that there must also be psychological remnants of each sex, and thus we are all bisexual. Clearly, such a perspective ignores the role of society in orienting us toward a sexual partner and it stresses the biological input. Freud felt that since humans are biologically bisexuals, they all have to work through the homosexual interest they have in order to become heterosexual. I should note that present-day biologists would reject any notion of an innate bisexuality in human genetic inheritance. In fact, as Judd Marmor has pointed out, so would many psychiatrists. 17

According to Freud's psychosexual developmental theories, males were to work out their homosexual tendency during the oedipal stage by identifying with their father and his values. Males with a hostile or absent father and a dominating and seductive mother were unable to work through this stage and they therefore became homosexuals, unable to "advance" to the ultimate heterosexual level. Freud further believed that even those who worked through this stage had some latent homosexuality in them that could come out later in life. Most of his theory deals with male homosexuality, although he does offer an analogous explanation for female homosexuality.

I believe that the orthodox Freudian viewpoint is an expression of the widespread public belief that homosexuals were produced by "abnormal" family relationships. Most of the attempts to find such "pathological" family causes of homosexuality concluded that such descriptions apply only to a minority of homosexuals.18 The well-known empirical work done by Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith reports that factors like detached hostile father, mother-dominated father, prudish father, unpleasant mother, negative relationship between parents, and other family-related factors are only weakly related to homosexuality. They stress that all such factors taken together account for only a minority of homosexual behavior.19

The most important direct influence on homosexual orientation in the Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith study was the presence of childhood gender nonconformity. Childhood gender nonconformity was the best single predictor of adult homosexual preference. Gender nonconformity refers to being unlike the societal expectations for your gender. Bell and his colleagues measured this key variable by asking about childhood liking for typical male and female play activities and for self-judgments regarding childhood feelings of being masculine or feminine. They summed up this major finding by saying:20

One of the major conclusions of this study is that boys and girls who do not conform to stereotypical notions of what it means to be a male or a female are more likely to become homosexual. (Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith, 1981: p. 221)

Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith conclude their report by saying that since family factors explained only a minority of the causes of gender-role nonconformity, then the nonconformity might well be due to biological factors. Here, I would again respond by pointing out that such an assertion is without clear meaning until one locates specific biological mechanisms that can be shown to produce homosexual responses. Otherwise, it simply states the obvious - of course, homosexuality may be due to unknown biological causes, or to unknown psychological causes, or, to be sure, to unknown sociological causes. As long as the specific identity of the unknown possible cause remains unclear, we have added very little to our understanding of homosexuality.

Officially, the psychiatrists in 1973 removed homosexuality from their list of disorders, but they later added egodystonic homosexuality, a category that refers to homosexuals who are unhappy with their homosexual object choice.21 There is no analogous category for egodystonic heterosexuality as a disorder; thus it is clear that psychiatrists are still eyeing homosexuality with suspicion.

It is interesting to note that although orthodox Freudians would contend that there is a biological basis for the tendency in all of us to go through a homosexual stage, they would also contend that we can learn to repress and not act upon these homosexual pressures. Thus, holding a biological causation position does not stop such psychiatrists from feeling that change is possible. This is important to state so that those who believe that the acceptance of biological causation will remove the desire to change homosexuals will see that this does not necessarily follow. 22

Lest I leave the impression that all psychiatrists and psychologists view homosexuality as an abnormal condition, let me quote from Judd Marmor a well-known psychiatrist who has written extensively on homosexuality : 23

In the final analysis, psychiatric categorization of the development of homosexual preference as a form of "disordered" sexual development is simply a reflection of our society's disapproval of such behavior, and psychiatrists, whether they realize it or not, are acting as agents of social control in putting the label of psychopathology upon it.... The labeling of homosexual behavior as a psychopathological disorder, or "perversion," however honestly believed, is an example of defining normality in terms of adjustment to social conventions. (Marmor, 1980: p. 396.)

Marmot's view here is quite congruent, as far as it goes, with my approach to normality, which I explicated in the last chapter. It expresses my sociological judgment concerning the normality of homosexuality. The widespread notion that a heterosexual bias exists in our human makeup is simply a way of extolling the virtue of the dominant sexual partner orientation. As I have noted before, the heterosexual bias position is in accord with the fourth tenet of the nonequalitarian sexual ideology. As such, it is quite popular in the Western world; but from a scientific point of view, convincing evidence has not been presented.

A CROSS-CULTURAL OVERVIEW

Let us proceed toward the explanation of same- and cross-gender partner orientations by examining how homosexuality operates in a variety of human societies. In many cultures although heterosexuality is favored, homosexuality is also encouraged. Apropos of this are in Siwans in Africa, where every married male has a teenage boy for anal intercourse but is also expected to be interested in sexual relationships with his wife. In our own heritage the Greeks, at least in the male aristocracy, combined homosexual and heterosexual behavior.

In light of the commonness of homosexual behavior, it would indeed be difficult to believe that any rare sort of biological or psychological factor is necessary for its occurrence. This commonness leads one to ask further, are there entire societies that not only have homosexual behavior but prefer homosexuality over heterosexuality? Relevant to this query, I will describe one most interesting society. Gilbert Herdt studied the Sambia in the highlands of Now Guinea from 1974 to 1976.24 Like many highland New Guinea societies, this one displayed a high degree of male dominance, hostility toward women, and rigid segregation of gender roles. The Sambia are a patrilineal society wherein men hunt and women garden. Traditionally, the Sambia have had a great deal of warfare with neighboring tribes. They often take wives from hostile villages and in return marry their female children to males in those villages (called "delayed marital exchange"). Girls marry when they are 12 to 15 years of age and boys are about 5 or 10 years older than the girls they marry.

They are a prudish society and forbid all heterosexual premarital coitus. Female genitalia even in infants is most often covered. Shame is used to control sexual behavior and attitudes. Virtually all marital coitus conforms to the male-on-top position. Fellatio is desired but cunnilingus is disparaged, as is heterosexual anal intercourse. All loss of semen is viewed as potentially dangerous and as weakening male strength. Therefore, marital coitus must be done in moderation.

The Sambia ritualize homosexuality in ways not common in most New Guinea groups. Other reports had spoken of such practices, but it was Herdt who studied and described these rituals in the greatest detail. Homosexuality in the Sambia was distinctive because of the length of time it involved in a male's life. Starting at about ages 7 to 10 boys would be introduced to a homosexual ritual that would be part of their life for the next 10 to 15 years. The Sambia believe that male children are vulnerable and that full masculinity is difficult to achieve. In order for male children to be able to produce sperm and impregnate their wives, these boys must ingest semen orally from mature males.

Such a belief, causally relating sexual maturity to childhood sexuality, is not uncommon. I mentioned this general type of belief in the Lepcha and Tiwi societies, where it was believed that female childhood sexuality promoted female pubertal development. People in these societies notice that children have sexual encounters and afterward puberty does occur, and this sequencing verifies to them their causal perspective. Such reasoning is, of course, an example of what the philosophers would call the "after this, therefore, because of this" fallacy.

In Sambia this homosexual ritual is the mechanism by which semen is transferred from older males to prepubertal boys. The ceremony is described by Herdt as a "penis and flute" ceremony. Bamboo flutes are played and they are also used to illustrate the mechanics of fellatio. The belief is passed on that fellatio causes the boy's penis to grow to the size of the older male whom he is fellating. In addition, if he partakes of sperm every day for several years, he will be strengthened and be able to eventually produce his own sperm. Note that this homosexual ritual is viewed as preparing the male for being able to impregnate his wife in heterosexual coitus. In addition, it is the way in which other manly traits of strength and courage are obtained. So Herdt is quite correct when he states that transitional homoeroticism is the royal road to Sambia manliness. (Herdt: 1981: p. 3)

In accord with their modest view of sexuality, these homosexual acts are not carried out in a group setting but rather occur outdoors when the two males are alone.

When the boy reaches the age of 15 or so, he then becomes the insertor for younger males. The age difference is important, for it is not proper for two boys the same age to engage in fellatio. It is also believed not proper for friends to engage in fellatio, but it is acceptable for enemies to do so. This fact plus the age difference in insertor and insertee would lead one to believe that interpersonal power is involved in these ritual relationships just as it is in future marital heterosexual relationships. In marriage the male will be the insertor and the dominant one. The hostility present in male-female relationships is congruent with the accent on dominance in such sexual interactions.

After marriage and parenthood the male must cease all homosexual relationships and does not participate in the ritual that leads to such behavior. Herdt estimates that "no more than 5% of the entire male population" become preferentially homosexual in their behavior (p. 252). We have no measure of how many males may be utilizing homosexual erotic imagery in their heterosexual behavior, but the implication is that it would be few. One of the attitudes that helps stop homosexual fellatio for married men is the belief that the wife's vagina infects the man's penis.

To introduce the penis (contagiously infected by the wife's vagina) into a boy's mouth would be a dangerous, polluting act. Most men do in fact become exclusively heterosexual after marriage. (Herdt: 198 1: p. 25 2)

Herdt points out that this form of transitional homosexuality has been found in other Melanesian societies such as the New Hebrides, Kiwai Papuans, Keraki Papuans, Baruya, Etoro, Kaluli, and Marind-Anim. 25

The length of time occupied by these practices seems long in the Sambia case, but in the Etoro, who also live in New Guinea, there seems to be an equally long involvement in such homosexual preparation for heterosexual manhood. Further, the fear of loss of strength through heterosexual coitus is perhaps even stronger in the Etoro.26 The Etoro actually forbid heterosexual coitus for over 200 days a year as a control on bodily weakness due to semen loss. These people note that after orgasm a man is out of breath, and they compare that to an old man who seems frequently to be out of breath. Then they relate the two events by saying that it is heterosexual coitus that ages one and leads to old men being out of breath.

Fears about the weakening effects of homosexual interactions are not as common, for homosexual acts are not seen as taxing one's strength as much as heterosexual acts. Still, homosexuality is supposed to be a youth's preparation for adult heterosexuality, and thus adult males endanger themselves if they continue to participate in homosexuality.

As we have seen, these societies have an endorsement of homosexual behavior for at least a time in a man's life. Yet we must be aware that most men would define the homosexual behavior as a masculinizing event and one that prepares them for heterosexual behavior. In that sense the societal focus still seems to be on heterosexuality, but with a great deal of anxiety involved. Also, we must distinguish the acceptance of homosexual behavior from the acceptance of a preference for homosexual behavior. Herdt, in talking of the Sambia, sums up this view by saying that homosexual behaviors do not equal a homosexual identity. They themselves would not accept that label, for their experiences lead mostly to exclusive heterosexuality and fatherhood. (Herdt: 198 1: p. 319)

Despite their heterosexual priorities, these Melanesian societies would surely think of homosexual behavior as perfectly normal and acceptable. In fact, they would unquestionably call it an essential part of their life as a man. Therefore, the Sambia represent a type of society in which homosexual behavior is viewed as normal. There would be no belief in Sambia, as there is throughout the West, supporting the abnormality of homosexuality. Unfortunately, little has been written about female homosexuality in these cultures, and so I cannot make any comparative analysis. 27

Let us look at cultures we are somewhat more familiar with, such as those in Polynesia, South and North America, North Africa, or the Mediterranean. In these cases we will find less, but still some, male homosexuality that is in part at least thought of as acceptable.

I have already mentioned that in Polynesia each village may have a mahu, or a male who may be a transvestite in that he can choose to dress like a woman. This male is also believed to be a homosexual in his behavior and preference. It is considered acceptable for males to engage in homosexual behavior with the mahu, providing this is not their preferred mode of behavior. Levy describes this practice as still present in modern Tahiti. 28

Many North American Indian societies allow cross-dressing, or transvestitism. This is often called by the French name of berdache. We cannot be sure of the degree of association of such transvestite customs with homosexual behavior. 29 In some societies there is also the possibility of a change in gender, similar to what we spoke of in Chapter 4. In the Mohave Indian society there was the possibility of genetic males and females reversing their assigned gender and becoming an alyha (female) or a hwame (male). They could then engage in sexual relations with someone of the same genetic sex but who was in the cultural role of a member of the opposite gender. Thus, although such a couple would belong to the same genetic sex, they would have a heterosexual relationship according to the gender they had adopted.30 This change in gender was often marked by an initiation ceremony. These people could marry. There were some restrictions, for a hwame could not be a leader in war or in the tribe. Whatever sexual behavior occurs after this change in gender is accepted as normal by the Mohave. By my definition of homosexuality, the sexual behavior following such changes in gender would be heterosexual. In our society the same would be true in the case of a marriage of a genetic male transsexual and someone of the male gender. The important distinction of genetic sex and gender is highlighted in these examples. It is gender and not genetic sex that determines homosexual and heterosexual behavior.

In a review of cross-cultural homosexual practices, J. M. Carrier makes the important distinction between the insertor and insertee male homosexual roles. 31 He points out that in many South American, North African, and Mediterranean societies the male who is the insertor in oral or anal sexuality is not stigmatized, but the male who is the insertee is viewed as effeminate.32 There is thus the judgment that the insertee role is a female role and unacceptable for adult males. In many cases if the insertee is a boy, then even the insertee act is more acceptable, for a boy would not be judged by adult male standards.

Consider how this set of attitudes compares to those we have just examined in Sambia and elsewhere in Melanesia. There, too, it was an older teenage or adult male who had oral intercourse with a prepubertal boy. This was acceptable for both. Yet if an adult male were to play the insertee role, his behavior would be unacceptable. An adult male must play the dominant role. In ancient Greece adolescent boys were sexual partners who played the insertee role while the adult male played the insertor role.

One generalization here appears to be that it is acceptable to play the insertor role when the partners are "not men".33 Partners who are young boys or effeminate men are alike in being conceived as "not men," and that makes homosexual behavior acceptable, especially for the insertor. In most of these societies as noted, if an adult male played the insertee role, he would be condemned and would be labeled effeminate. Once an adult male insertee is labeled effeminate, he becomes an acceptable "not man" partner for insertors. This is so even though the insertee is often viewed as behaving improperly.

The masculine gender role most often restricts what sexual behaviors are acceptable in accord with a cultural definition of masculinity. (Recall our discussion of tenet 4 in the last chapter.) There seems to be social pressure for keeping the male emphasis on heterosexually and at least in part integrating sexuality with marriage and parenthood. Carrier sums up this viewpoint thus:

Exclusive homosexuality, however, because of the cultural dictums concerning marriage and the family, appears to be generally excluded as a sexual option even in those societies where homosexual behavior is generally approved. For example, the two societies where all male individuals are free to participate in homosexual activity if they choose, Siwan and East Bay, do not sanction exclusive homosexuality. (Carrier, 1980: p. 118)

In sum, it seems that many societies accept homosexual behavior under specific conditions. Also, there is widespread acceptance of homosexual preference for certain periods of one's life, in specific types of relationships. But few, if any, societies seem to promote homosexual preference as the main form of sexuality for most individuals for most of their lives.

The common occurrence and acceptability of homosexuality without any obvious consequences that produce psychological or societal distress supports the view that homosexual behavior is normal for our species and for human societies. Much of the data applies only to males, but what we have said generally fits what little we know of female homosexuality as well. The one difference seems to be that female homosexuality is less subject to such strong hostility in most societies. The dominance of the male societal role may lead to the exertion of more societal pressure on males to avoid even the appearance of a submissive femalelike role. We have seen that in many cultures around the world this pressure does not exclude all homosexual behaviors. Some forms of male homosexuality are viewed as proper for males, but some seem to symbolize the lower position of women and are culturally proscribed.

NEW EXPLANATIONS:

TWO PATHWAYS TO HOMOSEXUALITY

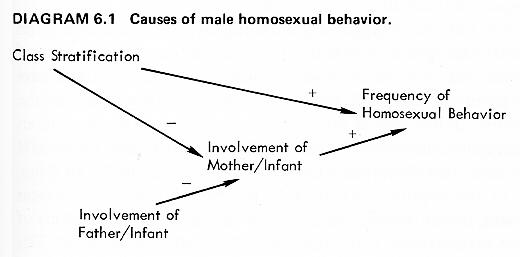

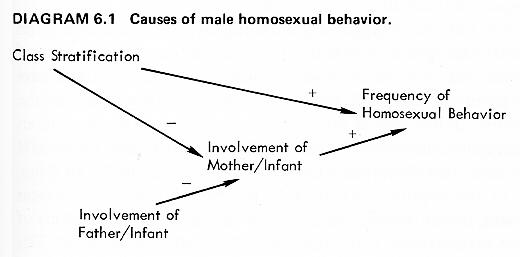

We have dealt with social forces that restrain the popularity of homosexuality. Another question concerns what social forces encourage homosexuality. As part of my examination of homosexuality cross-culturally, I analyzed the Standard Sample to ascertain which societal characteristics were associated with the prevalence of homosexuality. My warnings in earlier chapters concerning the limitations of these data are even more applicable to the codes developed for homosexuality. I used the code by Broude that indicated the frequency of homosexuality in a society.34 Her data applied only to male homosexuality. I carefully examined in a variety of ways the cross-cultural data from the Standard Sample. Only a few variables showed consistent and strong relationships to the frequency of homosexuality in a society. Note that I am speaking here only of males and only of homosexual behavior, not of homosexual preference. My results are presented in Diagram 6.1.

Diagram 6.1 indicates that those societies with more class stratification have more homosexual behavior and that those societies with high mother-infant involvement and low father-infant involvement also have more homosexual behavior. This diagram, like those in earlier chapters, is a causal diagram hypothetically presenting the variables in a time sequence going from the earliest causes on the left to the outcome explained on the right. As usual, only those variables and those paths that met all the statistical tests of significance are presented. (See Appendix A.)

A Freudian looking at this diagram might conclude that it supports the Freudian view that homosexuality is promoted by a close-binding mother and an absent or hostile father who together make the working out of the oedipal complex difficult. I have an alternative explanation that is much more sociological. Societies with high mother and low father involvement in infant care are often high male-dominant societies. The high mother and low father involvement with infants is a concomitant of the male-dominated system that in agriculture stipulates that fathers work the fields and get involved in the power structure instead of tending to their infants. In support of this interpretation, note that Diagram 6.1 does indicate a positive relationship of homosexuality with highly stratified societies. We know

DIAGRAM 6.1 Causes of male homosexual behavior.

|

that stratified societies are high on male dominance, and that is consistent with my thesis. 35

My position is that in male-dominant societies, the greater the rigidity in the male gender role, the greater the likelihood of producing male homosexual behavior. 36 If we grant that societies stress heterosexuality, then it makes sense to look for some of the causes of homosexuality in the way heterosexuality is promoted. This is a useful perspective both for societies that are hostile to homosexuality, as we are, or societies that encourage some homosexuality, like the Sambia.

I view sexuality, whether heterosexual or homosexual, as easy to accept because of its pleasure and disclosure aspects. Therefore, homosexuality may occur as an alternative or support for heterosexuality, as in the case of the Sambia society. But homosexuality may also occur because of difficulty or dislike for the heterosexual orientation, as in the United States and in much of Western Europe. Please keep in mind that I am discussing mostly homosexual behavior here. Such behavior may lead to homosexual preference, but the causal connections there require separate attention.

In a male-dominant society with low father involvement in infant care, the odds are increased of finding a male child growing up with little help in modeling his role after his preoccupied father. In such a society the male role is sharply delineated from the female role in terms of what is and is not permitted. Thus, the male gender role and its heterosexual component is more difficult to learn than it would be in a society that is less male dominant and less rigid in gender-roles. In addition, the more narrow and rigid a gender role is, the more likely individuals will find that role uninteresting and unpleasant. Individuals represent a wide range of interests and abilities; therefore, the narrower the gender role, the greater the proportion of people who will not be compatible with such a role.

In accord with this reasoning, I would suggest that the causal importance of mother-infant and father-infant involvement is rooted in the combination of gender-role segregation and male dominance that they reflect. The segregation of roles is rigidified when you add the element of male dominance. Male dominance will motivate males to guard and preserve their specialized gender behavior more carefully because it expresses their cultural dominance.

In an equalitarian and less segregated gender-role system, there would be much overlap as to what each parent would do; therefore the low participation of either parent would not matter as much in terms of learning gender roles. Where gender roles are segregated and unequal, then it does matter if the bearer of the dominant and very distinct father role is not often present. In such a case, genderrole acquisition by the male child would be more difficult and the outcome could well be to make that child feel like a gender nonconformist. The feeling of being out of step in terms of the requirements of one's gender role may lead to peer criticisms and to a young person feeling negative about the heterosexual aspects of the gender role. These events could make homosexual behavior more likely. The reader will recall that Bell and his colleagues concluded that such gender nonconformity on the part of children was the strongest predictor of homosexuality.37

Another socialization difficulty may occur when parents are radically different than peers in terms of heterosexual permissiveness. This may also lead to children feeling they are not conforming to their gender role. An illustration of this in American society would be when the antiheterosexual puritanism of parents prevented a male or a female from joining his or her peers in heterosexual activities. This, in turn, may lead to such youngsters feeling out of place in their gender roles in general and thus more likely to believe they are unable to participate in heterosexual courtship activities. Psychiatrist Judd Marmor endorses such a causal nexus: 38

A common finding in the backgrounds both of lesbians and male homosexuals is a strong antiheterosexual puritanism, stemming from either or both parents, that tends to color heterosexual relationships with feelings of guilt or anxiety. (Marmor, 1980: p. 17)

If we apply what I have said so far about pathways to homosexuality in a society like ours, we would conclude that our loosening up of gender roles and our greater acceptance of heterosexuality by parents as well as peers should have decreased the amount of homosexuality in America. Probably the most common opinion today is that homosexuality has not decreased in America. If we accept that common opinion, how do we reconcile this situation with our theory?

First let me note that the causes discussed above are both negative routes. That is, they are ways of becoming homosexual because of some problem with heterosexuality. But there are also positive pathways to homosexuality that I have not discussed. In a less gender-rigid and more sexually permissive society a person could feel freer to experiment with homosexuality, and that could well increase homosexual behavior. Such experimentation will produce the impression of greater homosexuality, but it may not establish any increase in homosexual preference - just an increased acceptance of homosexual behavior. That is what I judge the present situation to be in America.

I am not making an invidious comparison between homosexuality and heterosexuality and saying that without negative labeling of heterosexuality, homosexuality will not be preferred. Rather, the support for heterosexuality is so immense in all societies (even the Sambia) that only a small percentage will be able to resist the cultural pressures favoring heterosexuality. In that sense an increase in homosexual behavior is no guarantee of an increase in homosexual preference. Where the gender role encompassing heterosexuality is simple to achieve, it will be easier to return from any homosexual experimentation and conform to the heterosexual pressures present in the society.

Negative pathways to homosexual behavior apply predominantly to societies like those in the West, which are generally critical of homosexuality. Only in a homosexually hostile or indifferent society do we have to invoke some weakness in the heterosexual training as the cause of homosexual behavior. In this sense, almost all of our theories of homosexuality are culture bound, for they assume the absence of support for homosexual behavior. Some of these theories may have relevance for our type of society, but we need to start to develop explanations that apply to societies that are supportive of homosexual behavior. That is what I shall now attempt to do.

For societies like the Sambia, I would suggest a different interpretation of the causal relationships in Diagram 6.1. I have noted that societies with low father-infant involvement and high stratification typically are male-dominant societies. Such societies are likely to have male kin groups organized around both descent and residence (see Diagram 4.1 for findings on this point). The presence of such male kin groups may encourage males to identify more with each other. As in Sambia, this can be associated with a view that females are of less importance and inferior to males. Such a belief system could then more easily promote acceptable sexual relationships among men. This seems to be a more likely outcome than in a society lacking in male kin groups and male dominance. There is some empirical support for this position, for I do find that in the Standard Sample those societies high on the presence of male kin groups have more homosexual behavior than those societies medium or low on male kin groups. (See the correlation matrix, Exhibit A. 1, in Appendix-A.) This fits with the experimental research results of isosexual rearing of rhesus monkeys referred to earlier in this chapter (see note 6).

An interesting question that may arise here in the reader's mind concerns Western and Middle Eastern societies that also have high male dominance and emphasis upon male kin groups. Is the causal path suggested here a second more accepted route for the promotion of homosexual behavior in such societies? I think that the use of young boys or "feminine" adult males as insertees in homosexual behavior in many of these societies is congruent with this causal pathway notion. It may well be that sexual relations with "not men" are the way Western and Middle Eastern cultures have of informally accepting homosexuality for men who think of themselves as heterosexuals. In some of these societies this may be further encouraged by restrictive heterosexual customs. So, to this extent, we could say that this pathway to homosexuality, at least informally, also operates in the West. Note that this pathway stresses the fit of homosexuality with the heterosexual customs of that society. In this sense the presence of male kin groups does not establish competing customs but integrates homosexual customs with the dominant heterosexual emphasis.

Of course, my explanations for both the homosexually rejecting and accepting types of societies are speculative and require much further testing. Yet they do make sense of the relationships in Diagram 6. 1. There is one unifying theme in both types of explanations. It is the perceived fit with heterosexuality that is the basis for the attitude toward homosexuality. Those societies that perceive a mutual support of homosexuality and heterosexuality have different ways leading to homosexuality than those societies that perceive a hostility among the two major sexual orientations.

Accordingly, I offer two different types of explanations for homosexual behavior. Since we now know that many societies accept homosexual behavior, it would indeed be strange if precisely the same causal factors would produce such behavior in two such different social settings. Regardless of the accuracy of my explanations, it is time we insisted on explanations that are specific to the social context of homosexuality. The biological and Freudian explanations we examined earlier derive from a society that asserts that homosexuality is an unnatural act. They are not adequate explanations for even that type of society, and they are totally inappropriate for the Sambia type of society,

I further suggest that the same two pathways to male homosexuality exist for female homosexuality. Lesbianism can occur due to rigid female gender roles and/or due to the presence of supportive female groups. Analogously, in supportive societies the lesbian activity is likely to be construed to be integrated with heterosexual behavior in the long run. The work of lesbianism by Deacon (see footnote 27) supports this perspective. Since there is so little reporting on lesbianism, I cannot elaborate more here, but I do feel that there are theoretical reasons to expect that comparable explanations will apply to male and female homosexuality.

KINSHIP AND GENDER:

STRUCTURAL SUPPORT FOR HETEROSEXUALITY

Given the common occurrence of both homosexual and heterosexual behavior in human societies, one key question is, why aren't all human societies fully acceptant of homosexual and heterosexual behaviors? Humans are unique among the primates in the amount of exclusive homosexuality we have. Yet the point that almost everyone ignores is that humans are also unique in the amount of exclusive heterosexuality we have. Why are we so exclusive in our sexual choices? I think we are ready to answer that question now.

One set of reasons has been given: Heterosexuality is tied to the production of children, and children are considered desirable in virtually all societies. Even though many societies do not support a scientific view of the biological connection of coitus and pregnancy, they still see the connection of heterosexuality and children as existing in some fashion. Marriage is universally seen as the legitimation of parenthood, and parenthood in all cultures is expressed in the heterosexual kinship terms of mother and father. Thus, heterosexuality is almost certain to be encouraged. Children are also seen as the social security of one's old age and as the source of future supplies of warriors and workers. So, the heterosexual marital unions that produce children are valued for these reasons.

Gender roles are defined in terms of cross-gender (heterosexual) partner preferences. In good part this, also, is an outcome of marriage customs giving substance and meaning to the male and female gender roles. Gender roles are everywhere constructed with the marriage and family component writ large. No society has gender roles that omit conceptions concerning how that gender should behave and think in the area of marriage and the family. Thus, gender roles will most often either organize homosexual customs so as to make them supportive of marriage and family roles, as in the Sambia example, or restrict homosexuality in ways that they believe will prevent it from interfering with those roles.

We have seen that this dependency of gender role upon marriage customs does not mean that societies will condemn homosexual behavior; rather, it means that their acceptance of it will depend on its being integrated with the existing cross-gender sexual orientation .39 Sexuality, as I have described it, has the power to bind people together through their mutual physical and psychic pleasures. Most societies have used this power of sexuality to maintain the types of relationships they want. The importance of sexuality and the importance of marriage thus combine to produce a cross-gender sexual preference in virtually all societies we know about.

In some cases the societal desire to use sexuality to promote desired relationships can encourage homosexual relationships. This was the case among soldiers in some early Greek societies, where homosexuality was encouraged as a way to strengthen the willingness to fight for each other in combat. Nevertheless there are two sides to a boundary: It includes those within, but it also excludes those outside. Thus, when a religious institution or a political group wants to establish sharp boundaries separating it from others, there is pressure to exclude and thereby more clearly establish a distinct identity. 40 Many religious and political groups historically excluded homosexuals and viewed them quite negatively. In this sense, the custom of social boundary marking would be another cause of hostility toward "outside" groups such as homosexuals.

I will put forth another, somewhat more speculative, reason for the preference in society for cross-gender sexual partners. In almost all cultures we know about, males are given the more assertive, dominant, and aggressive role in the society (see Chapter Four). Given this fact, sexually joining two males would often involve placing two assertively trained individuals together, and a clash of wills over sexuality would therefore be more likely. Note that one of the most common settings cross-culturally for male homosexuality is when one male is older and therefore dominant over the other. Disputes over power are less likely in such a setting. Evidence from the Western world indicates that male homosexuals are not usually sexually exclusive and that in time, the sexual encounters between longterm homosexual mates become infrequent.41 Part of this is surely due to a search for variety, but it may also be due to a desire to avoid conflict and perhaps to find a sexual relationship with others that permits the kind of dominance or submissiveness that is preferred.

The same speculative reasoning concerning gender training in assertiveness exists for lesbian relationships. Placing two females together in a typical maledominated society would be placing two individuals together who are low on sexual assertiveness, and this might lead to low levels of sexual initiation by either partner. In fact, studies of lesbian couples do indicate just such low rates of lesbian sexual interaction compared to male homosexuals or to heterosexual couples.42

My thinking here is that in a male dominant society it is easier to unite in sexuality individuals who differ in their dominance desires and that given most societal norms, this is more likely to be a male and a female. Some of the research on friendships indicate that in the Western world, at least, male-male friendships are not as high on self-revelation as are male-female friendships.43 Male friends seem competitive and often relate only superficially. It is true that female-female friendships are high on self-revelation, but the problem of who initiates sexuality is not solved simply by high self-revelation.

In sum, I do believe that the major supports of heterosexuality are in marriage and gender constraints. Nonetheless, the dominance aspect of gender roles is worthy of our examination as a secondary cause. It should be understood, though, that even in male-dominated societies there are great differences in assertiveness and dominance within the male and within the female gender, and so, if desired, a difference in assertiveness can be achieved homosexually.44 It still follows, however, that if society trains men and women generally to be different in assertiveness and in dominance, then a difference in assertiveness will be easier to achieve in matches involving both genders as compared with one-gender unions.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The evidence from human and nonhuman societies supports the normality of homosexuality as a form of sexual expression. I hope our cross-cultural examination has given the reader some appreciation for the particular ways in which ideology, kinship, and power structure the integration of homosexuality in a society. To refer to our typology of general ideologies (see Chapter 5), I would say the Western world has taken an emotive ideological stance toward homosexuality and views homosexuality as a path that should not be offered as a choice. There has been some softening of this opposition. We do have half the states with consenting-adult laws. However, in terms of sexual ideologies, the Western world still seems to persist in endorsing tenet 4's stress on a heterosexual focus. We seem aware of only one way to focus on heterosexuality. In a sense the Sambia society also focuses upon heterosexuality; but instead of using avoidance as their means, they use the method of integrating homosexuality as a pathway to heterosexuality.

Perhaps of greatest importance in the comparative sociological approach to homosexuality is the awareness of the ways our society restrains even the nature of our scientific explanations. The view of homosexuality as a distortion of proper heterosexuality is analogous to our belief that communism is a distortion of proper political development. The provincialism of many of our therapeutic approaches to homosexuality should be obvious by now. My two interpretations of Diagram 6.1 can serve as a catalyst toward the growth of distinct theories for explaining homosexuality in different societal contexts. Yet there is also a need for a unified theoretical explanation. I hope the reader has noticed that I have explained homosexuality in both types of societies by reference to our kinship and gender systems - the same systems which explain heterosexual partner choices. All of this is the beginning of a unified, abstract explanation of all our sexual partner choices.

The examination of homosexuality in this chapter used the three basic societal linkage areas of kinship, power, and ideology that were developed in earlier chapters. By knowing that these areas are linked to all sexual customs, I found it was easier to search for explanations of different homosexual customs. I deliberately chose this area because of its centrality to a sociological understanding of sexuality and also because it is a controversial area that certainly illustrates how our ideological beliefs can color our understanding. The next chapter will continue to challenge your ability for dispassionate analysis. In the process it will display a few more components of my sociological explanation. Having come this far, I think you will enjoy the challenges of the next chapter, on the topic of erotica.

SELECTED REFERENCES AND COMMENTS

1. The National Opinion Research Center's (NORC's) annual survey of a representative sample of 1500 adult Americans is the source of information on attitudes toward homosexuality. The reader may have noticed that I also use this source for attitudes toward other sexual acts, such as premarital and extramarital coitus. For a quick assessment of national attitudes it is as good as any available source. However, for in-depth probing of such attitudes other research is preferable because NORC is aimed at covering a large number of attitude areas and it cannot cover each area in depth.

2. In a recent article Frederick Whitam noted that in the societies he checked, the percentage who preferred male homosexuality stayed within the 5-10% range. He assumes that this regularity affirms the biological basis of homosexuality. I would take issue with such a judgment. In order to establish a biological base in a scientific sense, one must locate specific biological mechanisms, not merely find a regularity. The reason for this becomes clear when we realize that there is a well-established regularity in the percentage of people around the world who enter into marriage - over 90%. Is getting married a biologically determined act? In many countries a quite similar proportion of males are employed outside the home. Does that make such male employment biologically based? There may be some biological base for homosexuality, but it won't be established by anything short of finding the specific linkages to biological mechanisms. I am striving to establish the societal base of sexuality by establishing the specific linkages to societal mechanisms. One cannot ask for less in the case of any biological, psychological, or other explanatory claims. For Whitam's views see

Whitam, Frederick L., "Culturally Invariable Properties of Male Homosexuality: Tentative Conclusions from Cross-cultural Research," Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 12, no. 3 (May 1983), pp. 207-226.

3. In the case of nonhuman species, I would substitute the words genetic sex for gender in my definition of homosexuality. This necessity further indicates the vast overlay of societal learning that is involved in our sexuality as compared to our primate cousins. This is not to deny learning has a place among other primates - it surely does - but that place is much smaller in importance.

4. The quote by Denniston comes from his chapter in Marmot's book on homosexuality. This book is one of the finest of the recent books on homosexuality. It contains chapters by people in various disciplines. Marmot himself is a psychiatrist, but not one who conforms to Freudian notions. He argues that homosexuality is rooted in biological, sociopsychological, and cultural factors.

No one can really argue with such a global assertion - there surely must be "some" roots in all three of those areas. By the same token, such a global statement, popular as it is, tells us very little of the specific ways in which these three levels operate. Some of the individual chapters in Marmor's book partially spell that out. My attempt in this chapter is to develop in some detail the sociological factors involved.

Denniston, R.H., "Ambisexuality in Animals," Chapter I in Marmot, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980, © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher,

5. Frank Beach is an authority on cross-species sexual behavior. See Chapter 11 in

Beach, Frank A. (ed.), Human Sexuality in Four Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

6. Goldfoot, David A., K. Wallen, D.A. Neff, M.C. Mcbriar, and R.W. Goy, "Social Influence upon the Display of Sexually Dimorphic Behavior in Rhesus Monkeys: Isosexual Rearing," Archives of Sexual Behavior. vol. 13, no. 5 (October 1984), pp. 395-412.

7. Sources for the prevalence of homosexual behavior in males and females in America can be found in Kinsey's work. Kinsey reports that 37% of the males and 13% of the females in his study reported having at least one homosexual orgasm. We lack more recent behavioral estimates, although we have good attitudinal measures in the research surveys by NORC. In England Michael Schofield's work is worth examining.

Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell Pomeroy, and Clyde Martin, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1948.

Kinsey, Alfred C., Wardell Pomeroy, Clyde Martin, and Paul Gebhard, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1953.

Schofield, Michael, Sociological Aspects of Homosexuality: A Comparative Study of Three Types of Homosexuals. Boston: Little, Brown, 1965.

8. Recent reviews of homosexuality cross-culturally do contain some valuable information and some good references. The list that follows should be a good start for the interested reader:

Carrier, J.M,, "Homosexual Behavior in Cross-cultural Perspective," Chapter 5 in Judd Marmor (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980,

Davenport, William H., "Sex in Cross Cultural Perspective," Chapter 5 in Beach, Frank A. (ed.), Human Sexuality in Four Perspectives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977.

Whitehead, Harriet, "The Bow and the Burden Strap: A New Look at Institutionalized Homosexuality in Native North America," Chapter 2 in Sherry B. Ortner and Harriet Whitehead (eds.), Sexual Meanings: The Cultural Construction of Gender and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

There are also books dealing with lesbian communities, lesbian couples, and theories about lesbians. I will mention only a few that are relevant to a sociological understanding. In all but the first book only sections deal with lesbianism.

Wolf, Deborah Goleman, The Lesbian Community, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

West, D.J., Homosexuality Re-examined. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977. (See especially Chapter 7.)

Paul, William, J.D. Weinrich, J.C. Gonsiorek, and M.E. Hotvedt, Homosexuality: Social, Psychological and Biological Issues. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1982. (See especially chapters 21, 22, and 23.)

Saghir, Marcel T., and E. Robbins, Male and Female Homosexuality. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1973.

Blumstein, Philip, and Pepper Schwartz, American Couples. New York: Morrow, 1983.

9. Of course, such estimates are subject to error, but my estimates are the same as those made independently by Judd Marmor. See page 7 in

Marmor, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

10. For additional arguments on the need to identify specific biological mechanisms in any assertion of causation, see my comments in note 2. The classic work by Bernard was

Bernard, Luther Lee, Instinct. New York: Holt, Reinhart & Winston, 1923.

11. Many studies have been undertaken to detect a correlation of time during the menstrual cycle with sexual desire. The results are highly contradictory, and so I conclude that there is no clear pattern.

12. Although I have great respect for the contribution Ellis made toward promoting the use of anthropological data and his avoidance of moral judgments about sexual behavior, I cannot resist informing the reader of some of Ellis's less scientific views about homosexuality. In his work on homosexuality he made a point of telling the reader that he believed that male homosexuals often could not whistle whereas female homosexuals were able to whistle and both were alike in their preference for the color green! The lack of an explanatory framework is obvious in his willingness to accept these features as informative. For an introduction to his work see the following:

Ellis, Havelock, Psychology of Sex: A Manual for Students. New York: New American Library, 1954.

Grosskurth, Phyllis, Havelock Ellis: A Biography. New York: Knopf, 1980.

13. Tourney, Garfield, "Hormones and Homosexuality, "Chapter 2 in Judd Marmor (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980. © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

14. Money, John, "Genetic and Chromosomal Aspects of Homosexual Etiology," Chapter 3 in Judd Marmor (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980. © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

15. For an overview of the place of hormones in sexual behavior, see

Goy, R.W., and D.A. Goldfoot, "Hormonal Influences on Sexually Dimorphic Behavior," Chapter 9 in R.O. Greep and E.B. Astwood (eds.), Handbook of Physiology: Endocrinology (vol. 2, sec. 7, part 1). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1973.

16. Freud, Sigmund, "Letter to an American Mother," American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 102 (1921), p. 786.

17. For a fuller expression of Marmor's qualification of Freud, see the Overview and Epilogue sections in his book

Marmor, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York, Basic Books, 1980.

18. One such recent examination takes an intriguing position contending that the pattern of distant or hostile father is a result of finding homosexuality in a child in a homophobic society. The distancing of the father is, in this view, not a cause of homosexuality and would not occur in a society that was less condemnatory of homosexuality.

Whitman, Frederick L., and Michael Zent, "A Cross-cultural Assessment of Early Cross-gender Behavior and Familial Factors in Male Homosexuality," Archives of Sexual Behavior, vol. 13, no. 5 (October 1984), pp. 427-440.

19. Bell, Alan P., Martin S. Weinberg, and Sue Kiefer Hammersmith, Sexual Preference: Its Development in Men and Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981, (See in particular Chapter 17.)

20. For information on this see Chapters 7 and 14 in the Bell, Weinberg, and Hammersmith book listed in note 19.

21. American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-3. Washington, D.C.: APA, 1977.

22. On a personality level, it may be that the popularity among homosexuals of a biological determination of homosexuality may rest upon the ability of this view to relieve the guilt that our society imposes on homosexuals. Our society's critical attitude toward homosexuality can easily make those who engage in homosexual acts feel that they are doing something wrong. A shared belief that such actions are biologically determined could reduce that self-blame.

23. Marmor, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980. © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

24. Herdt, Gilbert, Guardians of the Flutes: Idioms of Masculinity. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1981.

25. For a broader view of homosexuality in Melanesia see:

Herdt, Gilbert (ed.), Ritualized Homosexuality in Melanesia. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984. In some of these societies the males who are homosexually involved later on exchange sisters as their wives.

26. Kelly, Raymond C., "Witchcraft and Sexual Relations: An Exploration in the Social and Semantic Implications of the Structure of Belief," pp. 36-53 in Paula Brown and Georgeda Buchbinder (eds.), Man and Woman in the New Guinea Highlands.

27. There is one account of institutionalized lesbianism which I have come across that may be of interest.

Deacon, A.B., Malekula: A Vanishing People in New Hebrides. London: George Routledge, 1934.

28. Levy, Robert I., Tahitians: Mind and Experience in the Society Islands. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973.

29. The reader should distinguish between the concepts homosexual, transvestite, and transsexual. We have already defined homosexual. A transvestite is a person who cross-dresses, that is, dresses as does the opposite gender and gains erotic pleasure from that. It is problematic as to whether transvestites also are homosexual in behavior. In American society, most reports indicate that is not commonly the case. However, in other cultures the situation may well be different. In distinction from a transvestite, a transsexual is a person who feels encased in the wrong body and wants an operation to effect the change to the opposite genetic sex's body and to the gender role that goes with that genetic body. See the Glossary for future information on these and related concepts.

30. Devereux, G., "Institutionalized Homosexuality of the Mohave Indians," Human Biology, vol. 9 (1937), pp. 498-527.

For a general analysis of such customs see

Whitehead, Harriet, "The Bow and the Burden Strap: A New Look at Institutionalized Homosexuality in Native North America," Chapter 2 in Sherry B. Ortner and Harriet Whitehead (eds.), Sexual Meanings: The Cultural Construction of Gender and Sexuality. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1981.

31. Carrier, J.M., "Homosexual Behavior in Cross-cultural Perspective," Chapter 5 in Marmor, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980. © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

32. Carrier mentions a novel on sexual behavior in Marocco where there is a dialogue concerning a male who seeks anal intercourse indiscriminately with women, old men, and young boys. His companion asks him why he does this, and he answers that it is okay, for he is doing it to them and finally he says: "A zook is a zook. What's the difference? I niki it." (niki means fuck; zook means ass). This statement reveals much about the attitudes that prevail toward homosexuality from the insertor's viewpoint. See

Tavel, R., Street of Stairs. New York: Olympia Press, 1968. (See p. 53.)

33. The concept "not men" comes from

Karlen, Arno, "Homosexuality in History," Chapter 4 in Judd Marmor (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980.

34. Sanday also had a measure of homosexuality for societies in the Standard Sample. My examination of Sanday's measure of homosexuality raised serious doubts in my mind of its utility. I then spoke to Sanday, and she shared my misgivings and advised me not to use it. Thus, I was left with only Broude's measure.

35. One other point that needs comment: The relationship in Diagram 6.1 between class stratification and mother-infant involvement was negative, that is, the more stratification, the less mother-infant involvement. This is an unexpected result, but if we remember the negative relationship in Diagram 4.1 between agriculture and mother-infant involvement, it may become clearer. Agriculture encourages stratification by providing enough food for more people to reside permanently in one place. At the same time, this means more births for mothers and necessitates help in childcare from older children, grandmothers, and others. In that way both agriculture and stratification promote less involvement of the mother with her infants than was the case in hunting and gathering societies. The reader should keep in mind, though, that mothers in stratified, agricultural societies still do much more with infants than do fathers. The diagram shows that father involvement relates negatively to mother involvement so low father involvement counteracts the influence of class stratification on mother involvement.

36. There is an interesting cross-cultural study of 21 societies that reports a positive relationship between gender-role rigidity and violence. The requirement for males to be violent may also make conformity to the male role difficult. See

McConahay, Shirley A., "Sexual Permissiveness, Sex-Role Rigidity, and Violence across Cultures," Journal of Social Issues, vol. 33, no. 2 (1977), pp. 134-143.

37. For the detailed tables and diagrams of their study see

Bell, Alan P., Martin S. Weinberg, and Sue Kiefer Hammersmith, Sexual Preference: Statistical Appendix. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 198 1.

38. Marmor, Judd (ed.), Homosexual Behavior: A Modern Reappraisal. New York: Basic Books, 1980. © 1980 by Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. Reprinted by permission of the publisher.

39. For a psychological approach to this area see

Langevin, Ron, Erotic Preference, Gender Identity, and Aggression in Men: New Research Studies. Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1985.

40. Davies, Christie, "Sexual Taboos and Social Boundaries," American Journal of Sociology, vol. 87, no. 5 (March 1982), pp. 1032-1063.