|

|

|

Chapter Eight Permissive Standards and

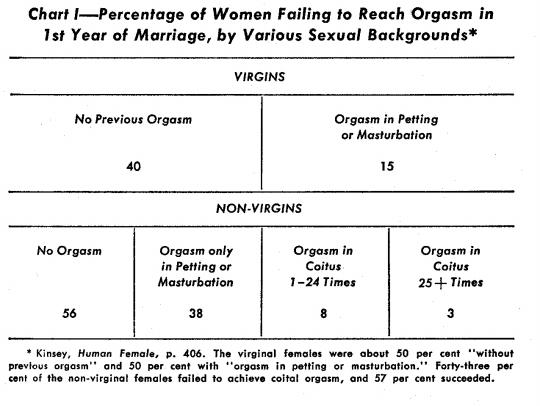

This does not mean that all three permissive standards are equally likely to lead to marital orgasm, nor to total sexual adjustment in marriage. There are factors relating to the interaction of both husband and wife which must also be considered. The individual's orgasmic history may have different consequences, depending on what standard underlies his experience and depending on the standard and experience of his mate.14 In the Burgess and Wallin study, many of the couples (married on the average about four years) were sexually maladjusted. Three out of four husbands and about one of every six wives said they had seriously contemplated extramarital coitus. About a fourth of the men and a third of the women stated that their sexual desires were definitely not being satisfied. Two out of every three wives said their husband's sex drive exceeded theirs. Over a fourth of the women rarely or never reached orgasm in all their years of marriage. Seven per cent of the men likewise rarely or never experienced orgasm. Love between the husband and wife seemed to help in achieving sexual adjustment, but there were many couples who were in love but who were maladjusted sexually. These love couples did not often divorce, thus indicating that, although sex is a vital part of marriage, there are so many other important parts that it is quite possible for the sexual factor to be outweighed.15 One cannot say for sure why these married couples and many others find sexual adjustment in marriage so difficult. Surely it cannot be explained solely by the lack of orgasm on the part of wives. Reasoning from the data possessed, it would seem that the type of premarital standard held by these people may be one important factor. Burgess and Wallin mention that the double standard encourages men to develop their sexual desires and women to inhibit their desires.16 This combination may be the crucial explanation of much of the sexual maladjustment in marriage. Men are made more desirous of sexual intercourse, women are inhibited, and then they are united in marriage. Sexual difficulties are thus most likely to occur. If people were trained more equally, a great deal of this could be avoided. Let me elaborate on this hypothesis and try to demonstrate why, in agreement with Burgess and Wallin, it is felt that the double standard in premarital intercourse is responsible for much of the sexual maladjustment in marriage. A double-standard man develops certain strong attitudes regarding sexual relations, as a result of his own experiences. Most likely his sexual behavior was aimed at self-satisfaction. Such a man builds up self-centered methods of sexual gratification and associates sexual relations with "bad" women, thereby disassociating sex and affection. Sexual relations in marriage, in our culture, are usually expected to involve mutual satisfaction with a woman respected and loved. The marital situation, then, is nearly as diametrically opposed to double-standard sexual relations as possible. The old double-standard attitudes and habits must be forgotten and new habits built up to replace them. The husband must learn to respect his wife; he must learn to associate sexual intercourse with tenderness and affection, rather than with disgust and lack of affection, and he must learn how to satisfy both his wife and himself and not only himself. This is an extensive change, and, in many cases, it may cause difficulty. No doubt some men find the change too difficult to make and continue to practice self-centered, affectionless, sexual intercourse which leaves their wives unsatisfied and emotionally disturbed. Orthodox double-standard women (women who accept chastity for themselves but permissiveness for men) often feel that a double-standard man, because of his experience, is an asset. They prefer to marry such men and believe that this kind of husband would be able to teach them about sexual intercourse. Kinsey found that 32 per cent of the girls preferred non-virginal men for husbands, 23 per cent preferred to marry virginal men, and 42 per cent had no special preference.17 The above statements, concerning premarital intercourse of the double-standard type and its effects on marital sexual adjustment, bring such views into serious question. Double-standard men may be quite ignorant about person-centered coitus. Furthermore, such women often bring their own handicaps to the marital bed, and, combined with a double-standard male, there would seem to be a good chance of sexual maladjustment.18 An orthodox double-standard woman must live up to a rather strict code. Not only must she avoid intercourse, she must not allow herself to be too free in the area of petting. She may be in the group of women who have never experienced premarital orgasm in any fashion. The average girl marries in her twenties, after about five to ten years of dating. It takes a considerable amount of control, and probably inhibition, to abide by such a strict standard for all those years. Such strict behavior could be accomplished with greater ease in a more ascetic culture, but in our culture with its accent on sex and young people, it is most difficult for a female to so sharply curtail her sexual behavior. After learning to restrict behavior for many years, it is often difficult to lose inhibitions. As one married woman in the Burgess and Wallin study stated in her interview: You develop inhibitions before marriage. There's a stone wall then, and after marriage it's a little hard to get over the stone wall. I like to go as far as the stone wall. After that I don't respond.19 A woman like this can no more lose her inhibitions on the wedding night than the man can lose his self-centered sexual habits. At the very least, it will take time and understanding to chip away the veneer of culturally-imposed inhibitions. Such a woman would need a husband with a great deal of patience and love, in addition to an understanding of how to change his wife's sexual behavior. Even if the woman were an experienced female, she might still have difficulties due to the double-standard male's self-centered sexual attitudes. Finally, it should be added that a double-standard male may carry over his behavior and accept extramarital coitus. This may further disrupt the over-all marital relationship and, in particular, the sexual relationship. Such extramarital coitus may remove much of the personal, unique, stable, and affectionate aspects of marital coitus, making it all the more difficult to reach a satisfactory sexual adjustment in marriage. It is apparent that the double standard may set the stage for marital sexual maladjustment in a multitude of ways. Even the double-standard male who adheres to the transitional subtype will have had most of his sexual experience in a traditional double-standard body-centered way. His affectionate experience may help somewhat, but by and large, what has been said of the orthodox adherent should hold true for the transitional male also. It may well be the double-standard male who is responsible for some of the non-virginal women failing to reach orgasm. If the male is predominantly concerned about his own pleasure, he may not help his partner to achieve orgasm. It is hypothesized that the single permissive standards are not so strongly involved in marital sexual maladjustment. Since permissiveness without affection involves mutual satisfaction, it avoids inhibitions on the part of the female or selfishness on the part of the male. There may, however, be some adjustment difficulties here due to the habitual bodycentered, thrill-centered type of premarital coitus which these people have experienced. It may well be difficult to adjust to the stability of marital coitus. It is further hypothesized that permissiveness with affection, because of its accent on mutual satisfaction and affection, is well integrated with marital sexual relations. This standard builds up attitudes favorable to stable, affectionate relations, and prepares one for the kind of coitus involved in marriage. Person-centered coitus is the easiest for both men and women to accept without qualms, and thus it should lead to a high rate of orgasm in premarital copulation. Such premarital orgasm is correlated with marital orgasm.20 In summary, I should mention that although there is a very high correlation between premarital orgasm and marital orgasm, there may well be more to sexual adjustment than reaching a climax. Although it could be said that chances for reaching orgasm in marriage are higher if orgasm is experienced before marriage, this cannot be recommended as a cure-all. Many people are so strongly opposed to premarital coitus that the attempt to achieve orgasm in premarital intercourse may lead to strong guilt feelings and greater sexual difficulties than formerly existed. Chart I shows clearly how some experienced women had a more difficult time than the virginal women in achieving marital orgasm. Such women may be in part those who felt guilty about their premarital behavior. Furthermore, orgasm alone is no guarantee of adjustment, as can be seen in the above examination of the double standard. It is my hypothesis that it is the combination of male and female premarital sexual standards that is most important in marital sexual adjustment. Finally, it must now be clear that such sexual adjustment occurs in the context of a total marital relation and can affect and be affected by that relation. CONCLUSIONS ON ALL EIGHT CONSEQUENCES I have not gone into great detail to show how the subtypes of our three major permissive standards would vary. There is, of course, a great deal of similarity, but the consequences will vary in some crucial areas. This was touched upon only briefly during the analysis, because the research information is not yet precise and thorough enough to explain fully such subtype variations. It should also be noted that within any one subtype there is a range of individual variation. Here again, there is not full research information as to what variations in the consequences may occur because of such specific positional differences. I have tried to present what I feel is as complete an account as is objectively possible at the present time. The broad theoretical assumption that standards would be differentially integrated with consequences has been supported by the evidence of the last two chapters. In summary, it can be said that the particular association of standards and consequences which exists in a society depends on the nature of that society-that the associations I have discussed exist because of the kind of society America is. The picture of America, developed in all the earlier chapters, provides the context of the discussion on standards and consequences. On an over-all basis, permissiveness with affection is the permissive standard most closely integrated with the positive value consequences, such as psychic satisfaction, and most weakly integrated with the negative-value consequences, such as guilt feelings. This standard, on this account, seems to be well knit into modern society-particularly in middle- and upper-class groups, where such consequences seem most highly valued. The person-centered coital behavior which goes with permissiveness with affection, and the affection which also is involved in such behavior, seem to be of vital importance in explaining the resulting integration. The evidence indicates that, in our kind of society, it is affection which helps insure that one can avoid the negative-value consequences and achieve the positive-value consequences. Another feature of person-centered coitus is the monogamous aspect of the affair. The more affection present, the more monogamous the affair; in American society, this, too, increases the likelihood of achieving the positive-value consequences and avoiding the negative-value consequences. The women who accept the transitional double standard also have person-centered behavior. However, because these women allow men greater sexual freedom, the consequences of this behavior may not be the same as those for the permissiveness-with-affection women. Conversely, those affairs lacking in affectionate feelings and which are not monogamous, namely, those entailing body-centered coitus, seem to be more likely to lead to some of the negative-value consequences, as well as fail to achieve many of the positive-value consequences. Such body-centered affairs are those which largely follow from the double standard and permissiveness without affection, as well as those which are in violation of a person-centered standard. Even here such negative-value consequences are simply more likely-they are by no means inevitable. The Puritan view of our standards is thus often erroneous, i.e, many people who disapprove of premarital intercourse try to paint all such behavior as disastrous in its consequences and are particularly prone to exaggerate the risks of body-centered coitus. Body-centered coitus does seem to have higher risks, but in many cases the difference is slight, and in other instances caution can control much of the risk involved. As noted previously, these sexual standards seem differentially distributed by education and occupation classes- the lower classes having more adherents to the double standard, and the middle and upper classes leaning more toward permissiveness with affection.21 Permissiveness without affection is more difficult to locate in terms of its dominant focus in our social structure. There is evidence of adherents in both the very high and very low segments of our class system. In any case, it is interesting to note that although all classes probably have adherents of all our major standards, some of these standards are stronger in some classes than in others. This means that premarital intercourse is not the same, in its social and cultural significance, in the different sectors of the social structure. Future research is needed to discern the exact distribution of standards and, equally important, the reasons for such distribution. At present, it may be suggested that since social classes differ as to their knowledge, and evalulation of the eight consequences we discussed, one would expect the popularity of these three permissive standards to differ accordingly. Now that we have analyzed our three permissive standards we will turn in the next chapter to our formal standard of abstinence and see what characteristics and consequences are associated with this, our final premarital standard. 1. It is believed that the consequences examined here are the major positive consequences of premarital intercourse. Of course, others may well be brought out by future research. I am including here the ones which I now feel are most important. Such a list is always tentative. 2. Kinsey, Human Female, p. 306. 3. Terman, op. cit`, p. 344. About half of the females in this study were bothered by physical pain at initial intercourse. There also would be psychological qualms, for many others. 4. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., chap. xx. 5. Human Female, p. 288. This is the same rate of orgasm which married women achieved. 6. Ibid., pp. 306, 343. 6a. Ehrmann, Premarital Dating Behavior, pp. 251?66; Ehrmann did not find significant differences in the pleasure reactions by sex codes. 7. The last chapter showed evidence for the small percentage of guilt feelings present in premarital coitus. Burgess and Wallin show the high value of physical release to 143 of their subjects. See Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., p. 375. 8. Psychic satisfaction, of course, could be expanded to include the status rewards a double?standard male achieves for his "conquests." But the term is not being used in this sense here. I previously spoke of such other consequences when dealing with social condemnation in chap. vii and with the double standard in chap. iv. 9. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., pp. 371?74. 10. It is important to note that these last two consequences (physical satisfaction and psychic satisfaction) are the only intended (manifest) consequences of all the positive and negative consequences which will be examined. The other consequences are unintended (latent) but are causally related to coitus. Future research will likely reveal other unintended consequences of coitus. 11. The more intimate a relationship, the more one would expect pain at its break. However, a study of college students indicates that they recover from most broken love relationships with remarkable speed. Over two-thirds of the boys and girls "recovered" in a matter of weeks. See Clifford Kirkpatrick and Theodore Caplow, "Courtship in a Group of Minnesota Students," American Journal of Sociology, LI (1945), 114-25. 12. This is at times asserted today. See the 1958 edition of Landis and Landis, op. cit., p. 304. See also chap. xi of that book. Landis feels that having premarital coitus may fix the couple's attention too much on sex. This is a common view and it would be interesting to gather evidence on this. It is possible that the reverse is true, and that by abstaining one thinks more of sex because it is forbidden fruit. 13. See Kinsey, Human Female, p. 406; Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., p. 362; Terman, op. cit., p. 383. For more recent evidence on this point, see Kanin and Howard, op. cit. 14. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., chap. xx. This chapter contains one of the most recent and most extensive researches into the sex factor in marriage adjustment. Terman, op. cit., chaps. x-xiii. Terman found an even greater amount of sexual maladjustment in marriage than Burgess and Wallin did. Perhaps couples in the early 1940's (Burgess and Wallin sample) were happier than the couples in the 1930's (Terman sample). 15. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., chap. xx, p. 696. These authors found a moderate relation between marital success and sexual adjustment. It is however, difficult to say whether the marital success was the cause or the effect. Also many marriages with poor sexual adjustment were good in other ways. 16. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., pp. 695-97. 17. Human Female, p. 323. 3 per cent of the girls were undecided. 18. For an excellent literary example of this sort of maladjustment, see Maupassant, op. cit. See also: Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., pp. 659-60, for evidence that over 25 per cent of the women said their premarital sex attitude was one of disgust, aversion, or indifference. Almost 10 per cent of the men said the same. Terman, op. cit., p. 248, found 34 per cent of the women and 13 per cent of the men with such attitudes. 19. Burgess and Wallin, op. cit., p. 677 20. Kinsey, Human Female, p. 345 shows 91 per cent of girls having coitus with fiance only, had no definite regrets. This is highest of all groups. Of course, there are other factors in a marital relationship which may affect the sexual adjustment, besides one's past standards. However, in this section, only the relation between premarital standards and marital sexual adjustment is being examined. 21. It should be noted that Kinsey found that female sexual behavior did not vary as much by education or occupation classes. There were some differences such as lower-educational girls having coitus and petting at earlier ages and marrying earlier. However, Kinsey's data do not enable one to check whether, although the rates of coitus were similar, the lower-class group included more permissiveness without affection adherents. Kinsey, Human Female. chap. viii.

|

|

[Home] [Acknowledgments] [Contents] [Introduction] [Chapter 1] [Chapter 2] [Chapter 3] [Chapter 4] [Chapter 5] [Chapter 6] [Chapter 7] [Chapter 8] [Chapter 9] [Chapter 10] [Bibliography] |