Devita Singh

A

FOLLOW-UP STUDY OF BOYS

WITH GENDER IDENTITY DISORDER

A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements

for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education

University of Toronto

© Copyright by Devita

Singh (2012)

Reproduced here by permission of the author.

Devita Singh, Doctor of Philosophy

Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology

University of Toronto

Main Contents:

Abstract

This study provided information on the long term psychosexual and psychiatric outcomes of 139 boys with gender identity disorder (GID). Standardized assessment data in childhood (mean age, 7.49 years; range, 3–12 years) and at follow-up (mean age, 20.58 years; range, 13–39 years) were used to evaluate gender identity and sexual orientation outcome. At follow-up, 17 participants (12.2%) were judged to have persistent gender dysphoria. Regarding sexual orientation, 82 (63.6%) participants were classified as bisexual/ homosexual in fantasy and 51 (47.2%) participants were classified as bisexual/homosexual in behavior. The remaining participants were classified as either heterosexual or asexual. With gender identity and sexual orientation combined, the most common long-term outcome was desistence of GID with a bisexual/homosexual sexual orientation followed by desistence of GID with a heterosexual sexual orientation. The rates of persistent gender dysphoria and bisexual/homosexual sexual orientation were substantially higher than the base rates in the general male population. Childhood assessment data were used to identify within-group predictors of variation in gender identity and sexual orientation outcome. Social class and severity of cross-gender behavior in childhood were significant predictors of gender identity outcome. Severity of childhood cross-gender behavior was a significant predictor of sexual orientation at follow-up. Regarding psychiatric functioning, the heterosexual desisters reported significantly less behavioral and psychiatric difficulties compared to the bisexual/homosexual persisters and, to a lesser extent, the bisexual/homosexual desisters. Clinical and theoretical implications of these follow-up data are discussed.

Acknowledgements

There are a number of individuals who have contributed instrumentally in the various stages of the dissertation project and to whom I would like to express my most sincere gratitude.

First, to my supervisor, Dr. Ken Zucker, there are no words to express what your continued mentorship has meant to me. Thank you for graciously accepting me as a student seven years ago. Your impact in my life extends far beyond research and clinical training–you also helped me to develop as a person and I feel privileged to have worked with you. You have equally inspired, challenged, and, certainly, frustrated me. Looking back, however, it has been the most insightful and rewarding journey these past years. Your immense wisdom and insightfulness never ceased to amaze and inspire me, perhaps rivaled only by your astute attention to detail and editing skills. Thank you for allowing me to complete this fascinating project with you and for the endless hours discussing the meaning of it all. Perhaps most importantly, thank you for holding such high expectations of me. Your relentless ability to “push” me (and prevent me from “whining”) caused me endless grief, but alas helped to create this wonderful piece of work and fostered my growth in numerous ways.

I sincerely thank my thesis committee members for their invaluable contributions and insightful feedback that not only shaped this project in interesting ways, but also enhanced my learning. Dr. Michele Peterson-Badali, you have been instrumental in my Ph.D. research, first as the second reader for my M.A. thesis and now as a committee member for my dissertation. Your insight, feedback, and encouragement have been undoubtedly helpful, especially as I weathered seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Dr. Katreena Scott, I thank you for not only your intellectual commitment to this endeavor, but your ability to help me always remember to see the forest for the trees. I greatly appreciate your selflessness in always making time for me and your incredible capacity to problem solve. Dr. Susan Bradley, I am most grateful for your clinical insights. The commitment, empathy, and skills you bring to clinical work with children and their families have inspired me and provided me with skills which have enabled me to grow as a clinician. Dr. Lana Stermac, thank you for coming on board and offering your insights. Finally, to my external examiner, Dr. Michael Bailey, it was indeed my pleasure to have your insights and reflections on this project. Since I first read your book, I recognized your passion for understanding the lives of gender dysphoric children and was immensely pleased that you agreed to take on this role.

I express sincere gratitude and appreciation to the study participants, for without you this project could not come have come to fruition. Thank you for the hours spent sharing your stories–your candor made data collection enjoyable and added much depth and complexity to this project. Thank you to members of the Gender Identity Service who have been important supports and to the research assistants who tolerated my need for perfection as you entered the large volume of data needed for this project. I would also like to thank Dr. Ray Blanchard and Dr. James Cantor for your statistical support and clinical insights.

Finally, I think my family and friends. This arduous journey would not have been possible without your warmth, support, and patience with the inevitable stress associated with this project. To old and dear friends–Tomoko and Heidy–we have shared countless memories throughout the years and your support helped me complete this journey. Hamed, there are no words! You made so much possible and I am forever grateful for our friendship and for your kindness when I needed it most. Brian, thank you for being an amazing friend and the most patient person I have ever met. The many, many hours you spent listening to my venting and offering technical support made this journey substantially easier. Navin, your unconditional support has not gone unnoticed. To my parents, words cannot express the gratitude I have for unique ways in which you have both supported and encouraged me. Dad, thank you for always understanding and challenging me, and mom, thank you for inspiring me to be better than I think I am capable of. Finally, but by no means least, I sincerely thank my sister, Wanita. You get me in ways no one else can and made the most difficult phases of this project bearable.

Table of Contents

|

xiv |

|

|

xvi |

|

|

xvii |

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

|

|

3 |

|

|

1.2.1 Sex and Gender. |

3 |

|

1.2.2 Gender Role. |

4 |

1.2.3 Gender Identity.. |

4 |

|

1.2.4 Gender Dysphoria. |

5 |

|

1.2.5 Sexual Orientation. |

9 |

|

1.2.6 Sexual Identity. |

10 |

|

1.2.7 Transgender and Transsexualism. |

10 |

|

11 |

|

|

1.3.1 GID in Children. |

11 |

|

1.3.2 GID in Adolescents and Adults. |

14 |

|

15 |

|

|

16 |

|

|

1.5.1 The Therapeutic Model. |

16 |

|

1.5.2 Accommodation Model. |

18 |

|

1.5.3 Early Transition Approach. |

19 |

|

22 |

|

|

1.6.1 Diagnostic Reform. |

22 |

|

1.6.2 Is GID a Mental Disorder? . |

24 |

|

27 |

|

|

1.7.1 Gender Identity Outcome of Children with GID. |

27 |

|

1.7.1.1 Methodological Issues. |

31 |

|

1.7.1.2 Process of GID Desistence. |

31 |

|

1.7.2 Gender Identity Outcome of Adolescents with GID. |

34 |

|

1.7.3 Sexual Orientation Outcome. |

35 |

|

1.7.4 Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Outcomes in Boys with GID: Summary. |

40 |

|

1.8 Retrospective Studies of Homosexual Men: Summary of Key Findings. |

41 |

|

1.9 Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior and Sexual Orientation: Explaining the Linkage. |

43 |

|

1.9.1 Biological Explanation: Influence of Genes. |

43 |

|

1.9.2 Biological Explanation: Role of Prenatal Hormones. |

46 |

|

1.9.3 Psychosocial Explanations. |

48 |

|

49 |

|

|

1.10.1 Children with GID. |

49 |

|

1.10.1.1 Behaviour Problems in Children with GID. |

49 |

|

1.10.1.2 Comorbidity in Children with GID. |

53 |

|

1.10.2 Adolescents and Adults with GID. |

55 |

|

1.10.3 Suicidality and Victimization in Transgendered Populations. |

58 |

|

60 |

|

|

1.11.1 Rationale for the Present Study. |

63 |

|

1.11.2 Goals of the Present Study. |

65 |

|

67 |

|

|

67 |

|

|

2.1.1 Routine Contact for Research. |

68 |

|

2.1.2 Participant-Initiated Clinical Contact. |

70 |

|

2.1.3 Participation Rate. |

71 |

|

2.1.4 Demographic Characteristics of Participants. |

71 |

|

71 |

|

|

73 |

|

|

2.3.1 Childhood Assessment. |

73 |

|

2.3.1.1 Cognitive Functioning. |

73 |

|

2.3.1.2 Sex-typed Behavior. |

73 |

|

2.3.1.3 Behavior Problems. |

75 |

|

2.3.1.4 Peer Relations. |

76 |

|

2.3.2 Follow-up Assessment. |

76 |

|

2.3.2.1 Cognitive Functioning. |

77 |

|

2.3.2.2 Behavioral Functioning. |

79 |

|

2.3.2.3 Psychiatric Functioning. |

80 |

|

2.3.2.4 Psychosexual Variables. |

82 |

|

2.3.2.4.1 Recalled Childhood Gender Identity and Gender Role Behaviors. |

82 |

|

2.3.2.4.2 Concurrent Gender Identity. |

83 |

|

2.3.2.4.3 Concurrent Gender Role–Parent Report. |

87 |

|

2.3.2.4.4 Sexual Orientation. |

87 |

|

2.3.2.4.4.1 Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

88 |

|

2.3.2.4.4.2 Sexual Orientation in Behavior. |

89 |

|

2.3.2.4.4.3 Sexual Orientation Group Classification. |

91 |

|

2.3.2.5 Social Desirability. |

92 |

|

2.3.2.6 Suicidality Experiences. |

93 |

|

2.3.2.7 Victimization Experiences. |

94 |

|

96 |

|

|

96 |

|

|

3.2 DSM Diagnosis for Gender Identity Disorder in Childhood. |

100 |

|

3.2.1 Childhood Behavior Problems as a Function of Diagnostic Status for Gender Identity Disorder. |

100 |

|

3.2.2 Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Diagnostic Status for Gender Identity Disorder. |

101 |

|

101 |

|

|

3.3.1 Gender Identity at Follow-up. |

101 |

|

3.3.1.1 Criteria for Persistence of Gender Dysphoria. |

103 |

|

3.3.1.2 Rate of Persistence and Desistence. |

104 |

|

3.3.1.3 Persistence of Gender Dysphoria as a Function of GID Diagnosis in Childhood. |

105 |

|

3.3.1.4 Summary of Gender Dysphoric Participants. |

105 |

|

3.3.1.5 Odds of Persistent Gender Dysphoria. |

107 |

|

3.3.2 Sexual Orientation at Follow-up. |

108 |

|

3.3.2.1 Group Classification as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in Fantasy at Follow-up. |

110 |

|

112 |

|

|

3.4.1 Demographic Characteristics in Childhood as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

112 |

|

3.4.2 Demographic Characteristics at Follow-up as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

117 |

|

118 |

|

|

118 |

|

|

3.6.1 Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation at Follow-up. |

118 |

|

3.6.2 Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior and Year of Assessment. |

125 |

|

125 |

|

|

3.8 Childhood Behavior Problems as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation at Follow-up. |

126 |

|

128 |

|

|

3.9.1 Gender Dysphoria. |

128 |

|

3.9.1.1 “Caseness” of Gender Dysphoria on the Gender Identity Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. |

130 |

|

3.9.2 Recalled Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior. |

133 |

|

3.9.2.1 Recalled Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Group. |

135 |

|

3.9.2.2 Recalled Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior and Childhood-Sex-Typed Behavior. |

135 |

|

3.9.3 Sexual Orientation. |

136 |

|

3.9.3.1 Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

136 |

|

3.9.3.2 Sexual Orientation in Behavior. |

137 |

|

3.9.4 Parent Report of Concurrent Gender Role. |

139 |

|

140 |

|

|

3.10.1 Behavior Problems at Follow-up as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation: Maternal-Report. |

140 |

|

3.10.2 Behavior Problems at Follow-up as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation: Self-Report. |

142 |

|

144 |

|

|

3.11.1 Psychiatric Functioning at Follow-up as a Function of Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation. |

144 |

|

146 |

|

|

3.12.1 Suicidality Questionnaire. |

146 |

|

3.12.2 Suicidality on the Youth Self-Report (YSR)/Adult Self-Report (ASR). |

148 |

|

3.12.3 Parent-Report of Suicidality on the Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL)/Adult Behavior Checklist (ABCL). |

152 |

|

152 |

|

|

3.13.1 Descriptive Victimization Experiences for the Entire Sample. |

153 |

|

3.13.2 Victimization Experiences as a Function of Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

155 |

|

3.13.3 Victimization and Mental Health. |

158 |

|

3.13.4 Victimization and Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior. |

158 |

|

3.13.5 Victimization and Parent-Report of Concurrent Gender Role Behavior. |

159 |

|

3.14 Comparisons with Other Follow-up Studies of boys with Gender Identity Disorder. |

159 |

|

3.14.1 Persistence Rates across Follow-up Studies of Boys with Gender Identity Disorder. |

159 |

|

3.14.2 Threshold vs. Sub-threshold for Gender Identity Disorder. |

160 |

|

162 |

|

|

162 |

|

|

164 |

|

|

166 |

|

|

168 |

|

|

4.4.1 Gender Identity Outcome. |

168 |

|

4.4.1.1 Rate of Persistent Gender Dysphoria. |

168 |

|

4.4.2 Sexual Orientation Outcome. |

169 |

|

4.4.2.1 Rate of Bisexual/homosexual Sexual Orientation. |

169 |

|

4.4.2.2 Sexual Orientation of Persisters. |

171 |

|

4.4.2.3 Age and Sexual Orientation. |

171 |

|

4.4.3 Multiple Long-term Psychosexual Outcomes for Boys with GID. |

173 |

|

173 |

|

|

4.5.1 Demographic Predictors of Gender Identity Outcome. |

174 |

|

4.5.1.1 Social Class. |

174 |

|

4.5.1.1.1 Familial Stress and Parental Psychopathology. |

175 |

|

4.5.1.1.2 Quality of Peer Relationships. |

176 |

|

4.5.1.1.3 Attitudes towards Homosexuality. |

177 |

|

4.5.2 Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Predictor of Gender Identity Outcome. |

181 |

|

4.5.3 Behavior Problems in Childhood as a Predictor of Gender Identity Outcome. |

182 |

|

4.6 Variation in Persistence Rates across Follow-up Studies of Boys with GID. |

185 |

|

4.6.1 Sample Differences. |

186 |

|

4.6.2 Sociocultural Influences. |

190 |

|

4.6.3 Referred vs. Non-Referred Children. |

192 |

|

4.6.4 Treatment Experience. |

193 |

|

193 |

|

|

4.7.1 Theoretical Implications. |

193 |

|

4.7.2 Clinical Implications. |

195 |

|

4.7.2.1 Should Gender Transitioning be Encouraged in Childhood?. |

195 |

|

4.7.2.2 Effects of Treatment on Long-Term Gender Identity Outcome. |

198 |

|

4.7.3 Process of GID Desistence and Persistence Overtime. |

200 |

|

201 |

|

|

203 |

|

|

4.10 Behavioral Problems and Psychiatric Functioning at Follow-up. |

206 |

|

4.10.1 Behavior problems at follow-up. |

206 |

|

4.10.2 Psychiatric functioning at follow-up. |

208 |

|

4.10.2.1 Implications of Psychiatric Outcomes. |

209 |

|

4.10.2.1.1 Distress of Gender Dysphoria. |

209 |

|

4.10.2.1.2 Peer and Family Rejection. |

210 |

|

4.10.2.1.3 Minority Stress. |

211 |

|

4.10.2.1.4 Familial Psychiatric Vulnerability. |

214 |

|

215 |

|

|

4.12 Limitations of the Present Study and Future Directions. |

220 |

|

222 |

|

|

224 |

|

|

275 |

|

Table 1 |

Distribution of Recruitment Across Data Collection Period. |

68 |

|

Table 2 |

Demographic Characteristics of Participants. |

72 |

|

Table 3 |

Measures of Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior. |

74 |

|

Table 4 |

Follow-up Assessment Protocol. |

78 |

|

Table 5 |

Demographic Characteristics and Behavior Problems as a Function of Participant Status. |

97 |

|

Table 6 |

Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Participant Status. |

98 |

|

Table 7 |

Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Diagnostic Status for Gender Identity Disorder in Childhood. |

102 |

|

Table 8 |

Summary of Gender Dysphoric Participants. |

106 |

|

Table 9 |

Kinsey Ratings for Sexual Orientation in Fantasy. |

108 |

|

Table 10 |

Kinsey Ratings for Sexual Orientation in Behavior. |

109 |

|

Table 11 |

Demographic Characteristics in Childhood and at Follow-up as a Function of Group. |

113 |

|

Table 12 |

Correlation Matrix of Childhood Demographic Variables on which the Groups Differed. |

115 |

|

Table 13 |

Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Group Outcome at Follow-up from Demographic Variables. |

117 |

|

Table 14 |

Childhood Sex-Typed Behavior as a Function of Group. |

119 |

|

Table 15 |

Correlation Matrix of Childhood Sex-Typed Measures on which the Groups Differed. |

122 |

|

Table 16 |

Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Group Outcome at Follow-up from Demographic Variables and Sex-Typed Behavior. |

124 |

|

Table 17 |

Behavior Problems in Childhood and Follow-up as a Function of Group. |

127 |

|

Table 18 |

Psychosexual Measures as a Function of Group. |

129 |

|

Table 19 |

Mean Factor 1 Score on the Recalled Childhood Gender Identity/Gender Role Questionnaire. |

133 |

|

Table 20 |

Sexual Orientation in Fantasy and Behavior on EROS and SHQ. |

138 |

|

Table 21 |

Correlations between Behavior Problems in Childhood (CBCL) and Follow-up (YSR/ASR, CBCL/ABCL). |

141 |

|

Table 22 |

Number of Psychiatric Diagnoses at Follow-up. |

144 |

|

Table 23 |

Psychiatric Functioning at Follow-up as a Function of Group. |

146 |

|

Table 24 |

Suicidal Ideation and Behavior at Follow-up as a Function of Group. |

149 |

|

Table 25 |

Gender Identity-Related Victimization. |

154 |

|

Table 26 |

Mean Frequency of Victimization as a Function of Group. |

156 |

|

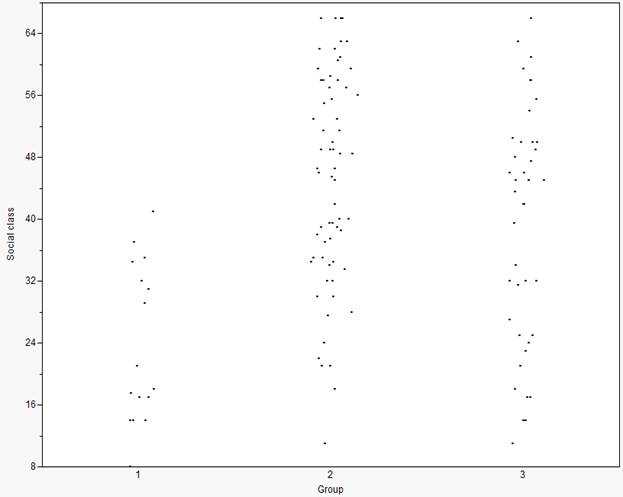

Figure 1 |

Distribution of social class for the outcome groups at follow-up. |

116 |

|

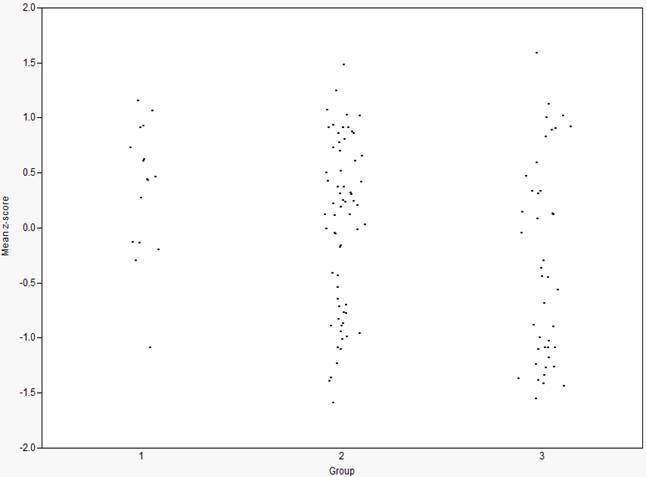

Figure 2 |

Distribution of the mean composite z-score for the outcome groups at follow-up. |

123 |

|

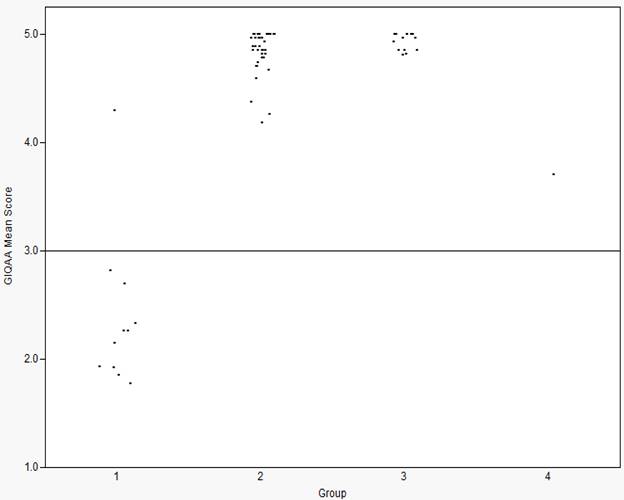

Figure 3 |

Distribution of the GIQAA mean score for the outcome groups. |

132 |

|

Appendix A |

DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Identity Disorder. |

275 |

|

Appendix B |

Proposed DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Gender Dysphoria in Children. |

277 |

|

Appendix C |

Phone Script. |

279 |

|

Appendix D |

Vignette: Parent Report on Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation |

281 |

|

Appendix E |

Participant-Initiated Research Contact: Reasons for Clinical Contact. |

283 |

|

Appendix F |

Research Consent Form. |

286 |

|

Appendix G |

Semi-Structured Interview to Assess Gender Identity Disorder in Biological Males. |

289 |

|

Appendix H |

Inter-rater Reliability for Kinsey Ratings of Sexual Fantasy and Sexual Behavior. |

292 |

|

Appendix I |

Suicidality Questionnaire. |

294 |

|

Appendix J |

Victimization Survey. |

297 |

|

Appendix K |

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation at Follow-up. |

303 |

|

Appendix L |

Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents or Diagnostic Interview Schedule Diagnoses at Follow-up. |

312 |

|

Appendix M |

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation Outcomes in Follow-up Studies of Boys with GID. |

323 |

Chapter 1

Introduction

Gender identity is usually a central aspect of a person’s sense of self and, once developed, appears to be less malleable as development progresses (e.g., Egan & Perry, 2001; Ruble, Martin, & Berenbaum, 2006). The development of one’s gender identity and, by extension, gender role, is more than a cognitive milestone as it impacts on virtually all aspects of human functioning. In childhood, significant sex differences are seen in such behavioral domains as peer, toy, and activity preferences (e.g., Fagot, Leinbach, & Hagan, 1986; Ruble et al., 2006; Zucker, 2005b). In adolescence and adulthood, significant sex differences are seen in psychosocial domains such as interpersonal relational styles (e.g., Maccoby, 1998) and career choice (e.g., Lippa, 1998, 2005). One can imagine the profound implications on the person whose gender identity development departs from typical pathways and which results in much distress for the individual, a phenomenon that is recognized clinically as Gender Identity Disorder (GID).

Green and Money’s (1960) seminal article on boys with “incongruous gender role” was perhaps the first attempt in the literature to label, describe, and characterize the phenotype of young boys who exhibited a pattern of cross-gender behavior. Fourteen years later, Green’s (1974) seminal book, “Sexual Identity Conflict in Children and Adults,” provided a comprehensive description of children who were “discontent with the gender role expected of them.” Since the publication of these early works and, certainly, with the introduction of GID to the psychiatric nomenclature in the third edition of the Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; American Psychiatric Association, 1980), tremendous progress has been made in understanding several aspects of this disorder. The phenomenology of GID is now fairly well documented (e.g., Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; Zucker, 2000, 2005a; Zucker & Bradley, 1995) and psychometrically robust assessment measures and procedures have been developed to allow for thorough diagnostic evaluation (for reviews, see Zucker, 1992, 2005b; Zucker & Bradley, 1995).

There are, however, some important gaps in the literature on children with GID, two of which are addressed in the current study. Although the natural history or outcome of boys with GID has received some empirical attention, the findings have not been consistent. Studies have generally found that not all boys with GID persist in having GID in adulthood and, in fact, the majority desist and have a homosexual sexual orientation. However, the rates of persistence of GID found across various studies have been variable, ranging from 2.3% to 30% (Green, 1987; Wallien & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008), but are considerably higher than the estimated prevalence of GID in the general population (Zucker & Lawrence, 2009). The reasons for this variability are a matter of conjecture as little is known about the factors that influence GID persistence into adolescence and adulthood. Further complicating the picture is the finding that some children with GID do grow up to have a heterosexual sexual orientation (e.g., Wallien & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). Thus, given the variation observed in the long-term gender identity and sexual orientation outcome of boys with GID, it is important to examine childhood predictors of outcome in a sample of boys with atypical gender development. Second, very little is known about the long-term psychiatric outcome of boys with GID as the follow-up studies to date have primarily examined gender identity and sexual orientation outcomes.

The present study aimed to fill these gaps in the literature on boys with GID. First, the study examined the gender identity and sexual orientation outcome of boys with GID. Second, the study examined psychiatric outcome at follow-up. Third, using the extensive assessment data collected during childhood, in conjunction with the follow-up data, the study attempted to identify within-group childhood characteristics that were predictive of variations in gender identity and sexual orientation outcome in adolescence and adulthood.

This chapter will begin with a review of relevant psychosexual terminology. Information about the phenomenology of GID in children, adolescents and adulthood is summarized, including associated psychopathology in children, adolescents, and adults with GID. Current controversies in the field, particularly with regard to diagnosis and treatment, are summarized. This is followed by the results of studies that have examined gender identity and sexual orientation outcome in boys with GID. The literature on the relationship between childhood sex-typed behavior and sexual orientation in adulthood is reviewed. The remainder of the chapter includes a conceptual framework for the study within the field of developmental psychopathology. The chapter concludes with the rationale and goals for the present study. Given that the present study was a follow-up of boys with GID, the literature summarized in this chapter is primarily on that of boys with GID.

1.2.1 Sex and Gender

The terms sex and gender have been used interchangeably in the literature (Muehlenhard & Peterson, 2011). In this thesis, sex refers to whether a person is biologically male or female. Some of the common attributes that distinguish a person as male or female include the sex chromosomes, gonads, and internal and external genitalia (Vilain, 2000). Gender refers to psychological and behavioral characteristics associated with males and females (Kessler & McKenna, 1978; Ruble et al., 2006).

1.2.2 Gender Role

The term gender role, originally coined by Money (1955), refers to those behaviors, attitudes, and personality attributes that are consistent with cultural definitions and expectations of masculinity and femininity (Diamond, 2002; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). During childhood, gender role is commonly operationalized according to certain observable behaviors, referred to as sex-typed behaviors, including peer preference, interest in rough-and-tumble play, dress-up play, toy preference, and so on (Ruble et al., 2006). These gender role/sex-typed behaviors are often construed as indirect markers of a child’s gender identity as they are, on average, sex dimorphic (Zucker, 2005b). For example, boys tend to be more active than girls and engage more in rough-and-tumble play (Maccoby, 1998). Boys, on average, prefer to play with toy vehicles and weapons while girls, on average, prefer to play with dolls and toy household items (Berenbaum & Snyder, 1995). The diagnostic criteria for GID are defined, in part, by a profound and pervasive non-conformity to sex-typed behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In children, quantitative measurement of sex-typed behavior is obtained through parent-report questionnaires as well as direct observation (Zucker, 2006a; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). In adolescents and adults with GID, descriptions of these childhood behaviors are obtained through retrospective self-report.

1.2.3 Gender Identity

Gender identity refers to a person’s basic sense of self as a male or female, that is, the inner experience of belonging to one gender (Fagot & Leinbach, 1985; Stoller, 1964). Most individuals develop a gender identity that is congruent with their biological sex, such that most biological females have a “female” gender identity and most biological males have a “male” gender identity. From a cognitive-developmental standpoint, gender identity refers to a child’s ability to not only accurately discriminate males from females, but to also correctly identify his or her own gender status as a boy or a girl. Within this framework, the development of gender identity is a cognitive milestone and is thought to represent the first stage in achieving gender constancy, that is, the understanding that being male or female is a biological characteristic and cannot be changed by altering superficial attributes, such as hair style or clothing (Fagot & Leinbach, 1985).[1] In typically developing children, gender identity is established by age 3, at which point children can correctly answer the question, “Are you a boy or are you a girl?” Gender constancy is, on average, established by age 7. The development of a gender identity carries affective significance, as evidenced by the intensity of children’s “emotional commitment to doing what boys and girls are supposed to do” (Fagot & Leinbach, 1985, p. 687). It is also evidenced by the pride with which young children announce their gender and the embarrassment experienced if they are mislabelled by others (Zucker, 2005c).

1.2.4 Gender Dysphoria

The term gender dysphoria refers to the subjective experience of dissatisfaction and discontent about one’s biological status as male or female (Fisk, 1973; Zucker, 2006a). The concept of gender dysphoria is fundamental to clinical work with children, adolescents, and adults with GID as it captures the distress that results from the incongruity between one’s biological/assigned sex and internal experience of gender identity (Cohen-Kettenis & Gooren, 1999; Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; Money, 1994). In the DSM-IV criteria for GID (Appendix A), Criterion A1 (“repeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, the other sex”) can be considered the most concrete and direct expression of gender dysphoria (Zucker, 2010a). There are, however, developmental influences on the way in which children, adolescents and adults express their gender dysphoria. Cognitive development, language capacity, and social desirability are among some of the factors that may influence an individual’s expression of gender dysphoria.

Young children may actually state that they are members of the opposite sex (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; for case examples, see Zucker, 1994; Zucker & Green, 1992). Although this misclassification could be related to the child’s age and cognitive development, it may also reflect the severity of the gender dysphoria if the child does truly believe he/she is of the opposite gender. However, most children with GID do not generally misclassify their sex and they know that they are male or female. Thus, when asked, “Are you a boy or a girl,” they answer correctly (Zucker et al., 1993); however, they will voice the desire to be of the opposite sex and find little that is positive about their own sex (Zucker & Green, 1992). Some children may express the wish to be of the opposite sex (i.e., implying that they know which sex they belong to) and simultaneously insist that they are of the opposite sex (e.g., Zucker, 2000, 2006c). These children may have confusion over gender constancy and may be uncertain whether changing aspects of one’s behavior (e.g., hair, clothing) will also change one’s gender. In fact, young children with GID demonstrate more cognitive confusion about gender compared to controls and appear to have a “developmental lag” in their gender constancy acquisition (Zucker et al., 1999).

There is some evidence that overt statements to be of the opposite sex tend to diminish with age. Older children with GID may not verbalize the wish to be of the opposite sex, perhaps for social desirability reasons (Bates, Skilbeck, Smith, & Benter, 1974). For example, they may have received feedback directly or indirectly from parents and peers regarding the appropriateness of their cross-gender wish (Bradley, 1999; Zucker & Bradley, 2004). During clinical evaluation, it is not uncommon for older children who are struggling with their gender identity to not endorse the desire to be of the opposite sex, but later in therapy reveal their cross-gender wishes once they have developed feelings of security in the therapeutic relationship. Indeed, during the preparation phase for the DSM-IV, this clinical observation served as the rationale for collapsing of the verbalized wish to be of the other sex with the other behavioral indicators of cross-gender identification (Bradley et al., 1991). In the DSM-III, the desire to be or insistence that one is of the opposite sex was a required criterion for the diagnosis. Zucker and Bradley (1995) conducted a re-analysis of data from Green’s (1987) follow-up study of effeminate boys and found some research data to support this clinical observation. Of the 60 boys seen in childhood for effeminate behavior, 47 were 3-9 years old and the remaining 13 were 10-12 years old. Of the 47 younger boys, 43 (91.5%) were reported by their mothers to occasionally or frequently state the wish to be a girl, compared to 9 (69.2%) of the boys in the older age group.

That overt statements to be of the opposite sex tend to diminish with age may not be a cross-national observation in children with GID. Wallien et al. (2009) compared a sample of children with GID seen at a specialized gender clinic in Toronto to a sample of children with GID seen at a gender clinic in the Netherlands on the Gender Identity Interview, which is a self-report measure of cognitive and affective gender identity confusion. An age effect was found for the Toronto patients such that the youngest children in the sample (5 years of age and younger) reported more cross-gender feelings than did the older children (6-12 years). In contrast, there was no significant association between age and scores on the Gender Identity Interivew for the Dutch patients. Thus, in the Dutch sample, older patients were as likely to report cross-gender feelings as younger patients.

For developmental reasons, there are limitations on children’s ability to think abstractly about gender and to evaluate the meaning of their gender dysphoria. It is not uncommon that when asked to list reasons for wanting to be of the opposite sex, young children with GID will provide concrete advantages. As an example, one 8-year old boy with GID asserted that it would be better to be a girl because they have better bands, such as the Spice Girls (Zucker & Bradley, 2004). The extent to which a child engages in sex-typed behaviors typical of the opposite sex and their rejection of activities and clothing typical of their own sex can be construed as surface indicators of gender dysphoria. Some children may experience discomfort with their sexual anatomy, which serves as another indicator of their felt gender dysphoria.

Adolescents and adults with GID are generally more straightforward than children in their expression about their unhappiness with their biological sex. In adolescents and adults with GID, verbalization of an intense discomfort with both primary and secondary sex characteristics and the desire for medical treatment (e.g., hormonal treatment, sex reassignment surgery) to address this discomfort is one of the most salient ways in which gender dysphoria is expressed (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2010; Zucker, 2010a). However, the experience of gender dysphoria does not necessarily imply a desire for sex-reassignment surgery as some adolescents are only interested in hormonal treatment for their gender dysphoria (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2010). Compared to children, adolescents and adults with GID, on average, have the cognitive and language capacity to think abstractly about their gender identity and gender subjectivity (i.e., beyond surface behaviors) and dialogue about the meaning of their dysphoria and its genesis. They are also more capable of discussing their anatomic dysphoria, which is often at the core of their distress (Bower, 2001). In such discussions, it is not uncommon for these individuals to express feeling trapped or having been born in the wrong body (e.g., Shaffer, 2005).

1.2.5 Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation refers to a person’s erotic responsiveness to sexual stimuli and is typically measured along the dimension of the sex of the person to whom one is sexually attracted, that is, whether one is attracted to a member of the opposite sex (heterosexual sexual orientation), the same sex (homosexual sexual orientation), or both sexes (bisexual sexual orientation) (LeVay, 1993; Zucker, 2006a; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Individuals who do not experience sexual attraction are referred to as asexual. Sexual orientation is often assessed with regard to at least two parameters: sexual orientation in fantasy and sexual orientation in behavior (Diamond, 1993; Green, 1987; Sell, 1997). The former refers to erotic fantasies experienced during sexually stimulating events, such as masturbation or while watching erotic pictures or movies, and the latter refers to actual sexual behavior, such as kissing and intercourse.

In contemporary sexology, the assessment of sexual orientation may include psychophysiological techniques to measure sexual arousal (Chivers, Rieger, Latty, & Bailey, 2004), semi-structured interviews (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948), and self-report questionnaires (e.g., Zucker et al., 1996). From the foregoing definitions, that gender identity and sexual orientation are distinct constructs is obvious, yet, unfortunately, these terms are often conflated (for discussion, see Drescher, 2010b). As discussed later, synonymous use of these terms has implications for how one conceptualizes therapeutic approaches to help children with gender dysphoria feel more comfortable about their biological sex.

1.2.6 Sexual Identity

Sexual identity refers to an individual’s experience and conception of their sexual attraction (Diamond, 2000). Thus, it is the individual’s recognition, definition/labelling, and acceptance of themselves as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual (Diamond, 2002; Savin-Williams & Diamond, 2000). It is important to uncouple the construct of sexual orientation from the construct of sexual identity as they are not always synonymous. For example, a person may be predominantly sexually aroused by homosexual stimuli but may not necessarily regard or accept himself as “homosexual” (e.g., Bailey, 2009; LeVay, 2011; Ross, 1983).

1.2.7 Transgender and Transsexualism

The word transgender is an informal (i.e., non-diagnostic) term broadly used to subsume expressions of gender variance or gender nonconformity regardless of whether criteria for GID are met. Typically, individuals who are considered transgendered exhibit significant cross-gendered behaviors or identity. Some adolescents and adults use the term as a self-label of their gender identity (e.g., “I am transgendered” or “I am a trans person”) (Lawrence & Zucker, 2012). The term does not imply a particular sexual orientation (Drescher, 2010b).

Transsexualism, used sometimes synonymously with GID in adolescents and adults (e.g., Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; Simon, Zsolt, Fogd, & Czobor, 2011), is not an official diagnostic category in the DSM-IV (APA, 2000), although it is a diagnosis in the ICD-10 classification system that is given to adolescents and adults (World Health Organization, 1993). The term male-to-female transsexual (MtF) refers to biological males who identify as and desire to live (or are actually living) as females, but does not imply degree of transition to the female gender role (e.g., presenting socially, taking cross-sex hormones, received some type of surgical intervention) (Cohen-Kettenis & Gooren, 1999).

1.3 Phenomenology of Gender Identity Disorder

1.3.1 GID in Children

Although GID was only first introduced to the psychiatric nomenclature in the third edition of the DSM (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), its historical background extends over 150 years ago with case descriptions of individuals who experienced conflict over what is now referred to as their gender identity (see Zucker & Bradley, 1995). The incipient DSM-III diagnoses, Gender Identity Disorder of Childhood and Transsexualism, have since been modified into one overarching diagnosis, Gender Identity Disorder, with distinct criteria sets for children versus adolescents and adults, which reflect developmental variations in clinical presentation. In the present revised fourth edition of the DSM, the diagnosis (Appendix A) requires the presence of two components: (1) evidence of a strong and persistent cross-gender identification, which is generally manifested as the desire to be, or insistence that one is, the other sex and/or through the adoption of cross-sex behaviors, and (2) evidence of persistent discomfort with one’s biological sex and/or a sense of inappropriateness in the gender role of that sex, which, in males, is manifested through such behaviors as aversion towards rough-and-tumble play (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The onset of cross-gender behaviors generally occurs during the preschool period, and signs of GID may be visible as early as two years of age (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003). Typically, the behavioral signs of GID precede overt statements about feeling like or wanting to be of the opposite sex (Green 1976, 1987). Parents of boys with GID often report that, from the moment their sons could talk, they insisted on wearing their mothers’ clothes and shoes and were predominantly interested in girls’ toys (Cohen-Kettenis & Gooren, 1999).

The phenomenology of GID in boys has been well-described elsewhere (e.g., Zucker & Bradley, 1995; Zucker & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008; Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003). Boys with GID experience a strong psychological identification with the other sex, as evidenced by an array of sex-typed behaviors more characteristic of females and a rejection of sex-typed behaviors characteristic of boys (Green, 1976; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Zucker (2002, 2008a) identified eight categories of sex-typed behavior relevant to the clinical picture of boys with GID: (1) identity statements, (2) dress-up play/cross dressing, (3) toy play, (4) roles in fantasy play, (5) peer relations, (6) motoric and speech characteristics, (7) involvement in rough-and-tumble play, and (8) statements about sexual anatomy. Boys with GID are usually interested in playing with girls’ toys, such as Barbie dolls, and are more intrigued by girls’ games and activities (e.g., skipping rope) than boys’ activities (e.g., hockey). Although they may be equally interested in play as same-aged peers, they tend to dislike and refrain from rough-and-tumble play and gravitate more towards female peers than male peers.

Some boys with GID do not typically object to wearing stereotypically masculine clothing (e.g., pants) in social settings, such as school, but will engage in cross-dressing when the setting is amenable (Zucker, 2010a) while others will insist on wearing female clothing in public and may demonstrate oppositional behavior if allowed to cross-dress only in private (e.g., Ehrensaft, 2011). In a recent approach to treatment of children with GID, some parents and clinicians allow and even encourage gender transition in childhood. Boys with GID treated within this approach demonstrate strong resistance to wearing male-typical clothing. Instead, they insist on dressing socially and privately in female-typical clothing and are allowed to do so as part of their social gender transition (for case examples, see English, 2011; Rosin, 2008; Spiegel, 2008).

In pretend and dress-up play, boys with GID often take on the female role (e.g., a princess or mother). As discussed earlier, some boys with GID express distress about being a boy and having a male body and some will verbalize the wish to be a girl (for clinical examples, see Zucker 2006c, Zucker et al., 2012b). Some boys with GID also experience “anatomic dysphoria,” which is a dislike of one’s genitals. They may verbalize this dislike, attempt to hide their genitals or pretend to have female genitalia (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Indeed, mothers of boys with GID rated their sons as experiencing higher dissatisfaction with their sexual anatomy compared to mothers of clinical and community control boys (Johnson et al., 2004; Lambert, 2009).

On a terminological note, in referring to children with marked cross-gender behavior, some authors avoid formal nosology (i.e., GID) and, instead, use alternative terms such as “gender nonconforming” or “gender variant” on the premise that these terms are less stigmatizing than GID. The issue in using non-standardized terminology is that the populations to which the term refers is less well defined. “Gender variant,” for example, may refer broadly to children who display varying degrees of cross-gender behavior, some of whom may meet diagnostic criteria for GID but others may not. Further complicating matters, it is not always clear in the literature whether “gender variant” was used as an alternative to GID or as a general term to represent all children with marked cross-gender behavior. Some authors, however, use these alternative terms when referring to children in non-clinical samples (e.g., Rieger, Linsenmeier, Bailey, & Gygax, 2008). In these cases, a gender nonconforming boy is one who is relatively feminine or less masculine compared with other boys and a gender conforming boy is one who is relatively unfeminine compared to other boys. In this thesis, GID is used to refer to children who meet criteria for GID and gender atypical/gender nonconforming is used when referring more broadly to children with marked cross-gender behavior whose GID status is unknown.

1.3.2 GID in Adolescents and Adults

A core characteristic of adolescents and adults with GID is psychological identification with the opposite sex (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). This generally manifests in the verbalization of an intense desire to be a member of the opposite sex. Some adolescents and adults with GID attempt to adopt the social role or “pass” as a member of the opposite sex through alteration of surface level physical attributes such as hair or clothing style. Another core characteristic of adolescents and adults with GID is discomfort with their sexual anatomy (anatomic dysphoria), though this is not experienced by all individuals with GID (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; Bradley & Zucker, 1997). Anatomic dysphoria may manifest as an interest in taking contra-sex hormones and, in some cases, receiving sex reassignment surgery to alter their physical appearance (Cohen-Kettenis, Delemarre-van de Waal, & Gooren, 2008; Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; de Vries, Steensma, Doreleijers, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011a; Smith, van Goozen, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2001; Zucker, Bradley, Owen-Anderson, Kibblewhite, & Cantor, 2008; Zucker, 2006a). Treatment for adolescents with GID typically involves biomedical interventions that facilitate the transition from one gender to another. It is also recommended and, at times, required that the adolescent also engage in psychotherapy, though with a different treatment philosophy compared to psychotherapy for children with GID (Zucker et al., 2011; Zucker, Wood, Singh, & Bradley, 2012a). In general, this approach to treating adolescents and adults with GID is uncontroversial, though there may be cross-clinic/clinician variations in timing of treatment (e.g., minimum age for cross-sex hormones).

1.4 Prevalence of Gender Identity Disorder

More than 25 years ago, Meyer-Bahlburg (1985) characterized GID as a rare phenomenon. While there have been no formal epidemiological studies on the prevalence of GID in children, adolescents, and adults, other lines of evidence suggest that Meyer-Bahlburg’s observation still holds true. Information about the prevalence of cross-gender behavior in children has come from studies using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983), a parent-report measure of emotional and behavior problems. The CBCL[2] has two items that measure cross-gender identification, “Behaves like opposite sex” and “Wishes to be of opposite sex,” which can be summed (range, 0-4) to provide a composite of gender identity. In a Dutch study of 7526 7-year-old twin pairs from the general population, 4.7% of children had a summed score (across the two items) of 1 or higher (van Beijsterveldt, Hudziak, & Boomsma, 2006). More recently, Steensma, van der Ende, Verhulst, and Cohen-Kettenis (2012) reported on 879 Dutch children (406 boys, 473 girls) from the general population followed prospectively for 24 years. The mean age in childhood was 7.5 years (range, 4-11 years). Fifty one (5.8%) of the 879 children were classified as gender variant (i.e., summed score on gender identity items was 1 or higher), which is similar to the percentage found by van Beijsterveldt et al.

Since the 1960s, a number of studies have reported estimated prevalence rates for GID in adults (for a review, see Zucker & Lawrence, 2009). Rates have varied, in part, depending on the inclusion criteria (e.g., including individuals who have had, at least, hormonal treatment but have not necessarily had any surgical interventions vs. only including individuals who have had sex reassignment surgery). For example, De Cuypere et al. (2007) estimated that 1 in 12,900 biological adult males in Belgium have GID, while Weitze and Osburg (1996) estimated a prevalence rate of 1 in 42,000 in Germany. The estimated prevalence rate in most other studies have fallen within this range (i.e., 1/12,900-1/42,000). Based on these estimated rates, it seems reasonable to presume that the prevalence of GID is low. In Steensma et al.’s (2012) prospective study, only 1 (0.1%) of the 879 participants, a biological male, had undergone gender reassignment (cross-sex hormonal treatment and surgery) when followed up in adulthood.

1.5 Treatment of Children with Gender Identity Disorder

At present, there are three general approaches that guide the clinical management of children with GID, each of which rests on its own conceptualization of gender identity development and GID. It is beyond the scope of this thesis to review in detail treatment approaches and the debates surrounding them (for detailed reviews, discussions, and clinical examples see, for example, Dreger, 2009; Stein, 2012; Zucker, 2001a, 2006c, 2007, 2008b; Zucker & Bradley, 1995; Zucker et al., 2012b).

1.5.1 The Therapeutic Model

In one approach, the goals of treatment are: (1) to circumvent the consistently observed sequelae of GID (e.g., ostracism by peers, depression), (2) to help children feel more comfortable with their biological sex, thereby reducing/alleviating gender dysphoria, (3) to increase the likelihood of desistance of GID in adolescence and adulthood, and (4) to alleviate co-occurring socioemotional problems in the child or difficulties within the family dynamic that may play a role in the child’s gender confusion (e.g., Meyer-Bahlburg, 2002; Zucker & Bradley, 1995; Zucker et al., 2012b). Dreger (2009) labeled this approach the “therapeutic model,” in contrast to the “accommodating” model described below. However, depending on the clinician’s theoretical perspective on the etiology of GID, the specific interventions used may vary.

Some clinicians view cross-gender behaviors as a result of inappropriate learning and attempt to extinguish them using principles of behavior therapy (e.g., Reker & Lovaas, 1974). Zucker et al. (2012b) proposed a multifactorial theory in which cross-gender identification is influenced by several factors, including biological, psychosocial, psychological, and psychodynamic variables. Within this framework, a biopsychosocial model of treatment is used to address the underlying factors that contribute to the child’s cross-gender identification (e.g., socioemotional problems within the child, family dynamics). In addition to therapy with the child, intervention may also include parent and/or family counselling. Some clinicians use a strictly psychodynamic formulation in which GID is viewed as a defense against distress and anxiety. Thus, psychodynamically informed therapy is used to address the underlying factors that perpetuate this defensive response (Coates & Wolfe, 1997). Regardless of the etiological framework, a common thread among these clinicians is the assumption that it is possible to modify a child’s gender identity (e.g., Meyer-Bahlburg, 2002; Zucker, 2008b). In a variation of the therapeutic approach, clinicians in the Netherlands place the emphasis of treatment on concomitant emotional/behavioral problems in the child as well as family dynamics rather than on direct attempts to modify gender identity (Cohen-Kettenis & Pfäfflin, 2003; de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012). The rationale for this approach is that, if the concomitant problems have contributed to causing or maintaining the gender dysphoria, then the dysphoria will likely disappear by addressing these problems. de Vries and Cohen-Kettenis have recently referred to the approach used in the Netherlands as the “Dutch approach.”

Both the Dutch approach as well as that espoused by Zucker et al. (2012b) utilizes a developmental perspective to treatment. When gender dysphoria persists from childhood into adolescence, it is less likely alleviated by psychological intervention and more likely to be treated by hormonal and surgical interventions (e.g., Cohen-Kettenis & van Goozen, 1997; de Vries et al, 2011a; Zucker, 2006). Thus, the therapeutic approach for adolescents is one that supports transitioning on the grounds that it will lead to better psychosocial adjustment (Zucker et al., 2011, 2012b).

The therapeutic model has faced intense criticism because some clinicians have claimed that, in addition to treating gender dysphoria, they were also preventing homosexuality, which they viewed as disordered (e.g., Rekers, Bentler, Rosen, & Lovaas, 1977). Some critics of the therapeutic model, and of Zucker’s approach in particular, view it as “homophobic” and similar to reparative therapy that has been used in attempts to change an individual’s sexual orientation (e.g., Pickstone-Taylor, 2003). Most contemporary clinicians emphasize that the goal of treatment is to resolve conflicts associated with the GID, regardless of the child’s eventual sexual orientation (Cohen-Kettenis, 2001; Zucker & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). Moreover, Bradley and Zucker (2003) have explicitly stated that they do not endorse the prevention of homosexuality as a therapeutic goal. However, some parents of children with GID who request treatment do so, in part, because they hope to prevent homosexuality in their child (Zucker, 2008c). The therapeutic approach has also been criticized on the grounds that it does not appreciate the distinction between children with GID (i.e., children with gender dysphoria) and children who show gender-variant behaviors but without concomitant gender dysphoria (e.g., Stein, 2012). Discussed later, this criticism is a reflection of a broader conceptual and diagnostic debate in the field regarding the conflation of GID proper with presumably innocuous cross-gender behavior.

1.5.2 Accommodation Model

A second approach to treatment of GID has been referred to as the “wait and see” or “accommodation model” (Dreger, 2009; Hill, Rozanski, Carfagnini, &Willoughby, 2005). Within this framework, there is no direct attempt to help the child feel more comfortable about their biological sex or to modify their cross-gender behaviors. Rather, parents are encouraged to support the child’s cross-gender behaviors in order to reduce feelings of stigmatization in the child and to promote the child’s overall adjustment (Ehrensaft, 2012; Menvielle, 2012; Menvielle & Hill, 2011; Menvielle & Tuerk, 2002;). Ehrensaft (2011), in her case description of a 6-year-old biological male, explained that, essentially, the family and therapist tolerate a state of “not knowing” until the child “unfolds an authentic gender identity and expression,” which may or may not be aligned with their biological sex. If a child’s “authentic gender self” is not aligned with their biological sex, early social gender transition is then supported (e.g., Ehrensaft, 2012). The accommodation treatment approach is viewed as supportive and accepting of children’s authentic gender role expression on the premise that it does not steer children down a particular gender path (e.g., Bocking & Ehrbar, 2005; Hill et al., 2005). It is arguable, however, that by allowing cross-gender behavior, one is, in fact, steering children down a cross-gendered path. More than two decades ago, Green (1987) speculated that boys whose parents do not attempt to discourage cross-sex behavior might be more likely to become transsexuals as adults. Within this treatment approach, there appears to be an assumption that gender identity can change as indicated by the recognition that some children who socially transition at an early age may want to reverse the gender role transition later on (Ehrensaft, 2012; Menvielle, 2012).

1.5.3 Early Transition Approach

A third, more recent, approach takes an extreme stance on childhood cross-gender behavior and has likely been fuelled by changing ideas about what constitutes appropriate expression of gender (Drescher, 2010a). In this model, pre-pubescent children with GID, sometimes as young as 5 years of age, are allowed and encouraged to socially transition from one gender to another (e.g., Vanderburgh, 2009; see also Brown, 2006; English, 2011; Rosin, 2008; Spiegel, 2008). There is no attempt to decrease cross-gender behavior and identification. A social transition may involve, for example, a biological male using a female name and registering at school as a female (e.g., Saeger, 2006). This approach is partly rooted in the assumption that the onset of cross-gender behavior is an indication of innate (cross) gender identity rather than as a sign of gender confusion or a GID. Further, it is argued that an early transition (i.e., before puberty) may circumvent associated mental health issues seen in individuals with GID (Vanderburgh, 2009). The role of the therapist is to help families navigate aspects of the transition process, such as advocacy within the social setting and educating families about the medical aspects of transitioning.

There are some serious concerns about this approach. The most striking implication of an approach that facilitates early transitioning is that it may steer some children down a transgendered path who might have otherwise not desired to transition as they progress in development. Proponents of the early transitioning model have not addressed how this approach fits conceptually or clinically with the finding that the majority of children with GID show a desistence in adolescence (e.g, Drummond et al., 2008; Green, 1987; Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). This is an important issue because an approach that encourages transitioning in childhood assumes that these children would persist in their GID into adolescence, which is not supported by the follow-up studies of children with GID.

There have been no quantitative follow-up studies on children who socially transition in childhood, probably, in part, because this approach is still relatively recent. However, one qualitative study conducted in The Netherlands suggests that socially transitioning children is not without its drawbacks (Steensma, Biemond, Boer, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011). In this study, 25 adolescents who had met criteria for GID in childhood were interviewed regarding stability/instability of their gender identity from childhood into adolescence, among other things. The results of two adolescent (biological) females are of relevance to this discussion. In childhood, these females were seen and treated as boys by other children and they dressed in male-typical clothing all the time. It is unclear, however, the extent to which these females were socially transitioned (e.g., name and pronoun use). In adolescence, both girls experienced a desistence of their gender dysphoria and wanted to live in the female gender role. Both girls found it a struggle to attempt living in the female role after having lived to some extent in the male gender role. One girl commented, “At high school, I wanted to make a new start. I did not want people to know that I had looked like a boy and had wanted to be a boy in childhood.” While it is arguable that an approach that supports social transition in childhood may be beneficial to children who will turn out to be persisters, it is not the advisable approach for children who will desist. The challenge, however, is the difficulty in predicting the gender identity outcome of very young children with GID (Steensma & Cohen-Kettenis, 2011).

To date, there is no consensus on the best treatment approach for children with GID. This state of affairs has been maintained by the paucity of empirical data on treatment and also, in part, by theoretical disagreements among clinicians about gender identity development and its malleability in childhood. As a point of agreement, proponents of both the therapeutic and accommodation model agree that, if it is apparent that an adolescent is committed to transitioning, the recommended treatment approach is to provide cross-sex hormonal therapy, to be followed by surgery, if desired, in adulthood. Unfortunately, the debate about therapeutics for children is far from over largely because of scant research attention in this area. There have been no rigorous treatment outcome studies on children with GID and, certainly, no randomized controlled treatment trials that have compared the effects of these therapeutic approaches on gender identity outcome (Bradley & Zucker, 2003; de Vries & Cohen-Kettenis, 2012; Zucker, 2001a). In addition, there have been no studies that compared any of the different treatment approaches for GID to a condition of no treatment. Beyond resolving debate, there is an even more important reason to evaluate treatment approaches. As noted previously, most children with GID seem to desist in their gender dysphoria by adolescence. It remains unknown whether the aforementioned treatment approaches are associated with different long term outcomes (e.g., persistence vs. desistence of GID, general psychiatric functioning, psychosocial adjustment).

GID is arguably one of the most contentious diagnoses in the DSM. A detailed review of the controversies surrounding the diagnosis is beyond the scope of this chapter, but can be found elsewhere (e.g., Bockting, 2009; Bradley & Zucker, 1998; Bryant, 2006; Drescher 2010a, 2010b; Hill et al., 2005; Meyer-Bahlburg, 2010; Wilson, Griffin, & Wren, 2002; Zucker & Bradley, 1995; Zucker, Drummond, Bradley, & Peterson-Badali, 2009). Essentially, one group of critics argue for a reform of the diagnosis while a second group question the legitimacy of GID as a diagnostic category.

1.6.1 Diagnostic Reform

One major criticism of the GID diagnosis is that it fails to differentiate between children who have both cross-gender identity (gender dysphoria) and pervasive cross-gender behaviors from those who show signs of pervasive cross-gender behavior but without the co-occurring unhappiness about their biological sex (i.e., without co-occurring gender dysphoria) (Bockting, 1997). In the current form of the GID diagnosis (Appendix A), the Point A criterion is met if a child has at least 4 of 5 markers of persistent cross-gender identification: the desire to be, or insistence that one is, of the other sex (Criterion A1) and marked/pervasive cross-gender role behaviors, such as peer and clothing preference (Criteria A2-A5). Critics have argued that Criterion A1 (which is viewed as capturing gender dysphoria) should not be condensed with criteria pertaining to cross-gender behaviors; otherwise, a child may receive a diagnosis of GID through demonstration of cross-gender behaviors but in the absence of gender dysphoria (e.g., Bartlett, Vasey, & Bukowski, 2000; Bockting & Ehrbar, 2005; Hill et al., 2005; Richardson, 1996, 1999; Wilson et al., 2002). The concern is that a diagnosis and subsequent treatment may be harmful to the child (e.g., Langer & Martin, 2004). Presumably, these critics are arguing that the absence of verbal statements of cross-gender identification or wish is an indicator that the child is not gender dysphoric, regardless of the degree of cross-gender behavior. However, as discussed earlier, a child may experience unhappiness with their biological sex but not verbalize it. It is conceptually possible for children to meet diagnostic criteria for GID if they endorse items A2-A5 and also express unhappiness about their sexual anatomy (i.e., anatomic dysphoria, Criterion B), but yet do not make explicit statements of wanting to be of the opposite sex. These children may actually be struggling with their gender identity and, without a diagnosis, the way in which the cross-gendered behaviors are managed may not be in the best interest of the child (Zucker, 2010a). From a clinical standpoint, however, it is not common for a child to express anatomic dysphoria but not verbalize cross-gender identification.

It has been recommended that the diagnostic criteria be revised such that a distinction is made between children who have both cross-gender identification (manifested as explicit statements of wanting to be of the opposite sex) and cross-gender behaviors from children who only demonstrate cross-gender behaviors (e.g., Bartlett et al., 2000). Zucker (2005c) suggested that one solution to this debate is a modification of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria such that it would be necessary for the child to systematically verbalize the wish to be of the opposite sex in order for the Point A criterion to be met. In a re-analysis of a parent-report measure of cross-gender identification, Zucker (2010a) found that children who frequently stated the desire to be of the other gender also showed more pervasive cross-gender behaviors. In part because of this finding, the DSM-5 Workgroup on GID has recommended that the persistent desire to be or insistence that one is of the opposite gender should be a necessary criterion for the diagnosis of GID. It is hoped that this change would result in a tightening of the diagnostic criteria and may better separate children with GID from those displaying marked variance in their gender role behaviors but without the desire to be of the other gender. The proposed revision to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for GID in children is summarized in Appendix B. The Workgroup on GID proposed retention of the diagnosis in DSM-5 with a name change (“Gender Dysphoria in Children”). In addition to statements of cross-gender identification (Criterion A1), children need to have at least 5 of 7 other manifestations of incongruence between expressed and assigned gender. In the proposed diagnostic criteria, rejection of sex-typical toys, games and activities, and anatomic dysphoria are part of Point A criteria. Point B criteria pertain to distress or impairment.

1.6.2 Is GID a Mental Disorder?

That GID is not a mental disorder and should, therefore, be removed from the DSM has been argued from at least four perspectives: (1) the GID diagnosis pathologizes normal variation in gender role expression, (2) children with GID are not impaired or inherently distressed, (3) the diagnosis was introduced to the DSM as a veiled attempt to repathologize homosexuality, and (4) GID is a childhood manifestation of homosexuality.

It has been argued that the cross-gender behaviors observed in children with GID are no more than normal, though sometimes extreme, variation in gender role behavior. The GID diagnosis, therefore, pathologizes children who exhibit harmless gender non-conformity and who are simply expressing their interests and inherent tendencies (e.g., Langer & Martin, 2004; Pickstone-Taylor, 2003). Proponents of the GID diagnosis argue that this line of thinking represents biological essentialism and is a simplistic view of a complex phenomenon that is influenced by biological, psychological, and interpersonal processes (Bradley & Zucker, 2003; Zucker, 2006b; Zucker et al., 2012b). Thus, while the critics who argue for a reform of the diagnosis recommend that the criteria should be more stringent to better distinguish gender dysphoric from non-gender dysphoric children with cross-gender behaviors, these critics argue that all children who receive the GID diagnosis are actually displaying nonpathological gender nonconformity.

The GID diagnosis has also been criticized on the grounds that it does not meet the criteria for a mental disorder because children with GID do not show evidence of inherent distress or impairment in functioning (Point D criterion), and, if they do experience distress or socioemotional difficulties, it is simply a reaction to social intolerance of their cross-gender behaviors (e.g., Bartlett et al., 2000; Menvielle, 1998; Wilson et al., 2002). Some argue that the disorder is more a reflection of a gender oppressive society rather than signaling a disorder within the individual (Ault & Brzuzy, 2009). Supporters of the diagnosis have provided compelling reasons to retain GID in the diagnostic nomenclature (Bradley & Zucker, 1998, 2003). For instance, clinic-referred children with GID sometimes verbalize significant unhappiness over their status as males or females and often state the desire to change themselves into the opposite gender (for clinical examples, see Zucker et al., 2012b; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). It is also argued that, even in the absence of explicit statements to be of the opposite sex, pervasive enactments of cross-gender fantasies, such as through role-play and dress-up, is a behavioral manifestation of underlying unhappiness with one’s biological sex (Zucker, 2006b).

On a more political level, it has been argued that the inclusion of GID into the DSM was a veiled political maneuver to repathologize homosexuality, which was simultaneously removed from the DSM at the time that GID was introduced (e.g., Ault & Brzuzy, 2009; Sedgwick, 1991). Zucker and Spitzer (2005) noted that the DSM-III included a diagnostic category of ego-dystonic homosexuality; thus, there was no need for a backdoor diagnosis to replace homosexuality. These authors also brought attention to the fact that several clinicians and scientists who recommended the inclusion of GID in the DSM had argued in favor of delisting homosexuality.

The strong association between GID in childhood and homosexuality in adulthood has also added to the controversy surrounding the diagnosis. Follow-up studies of boys with GID have found that the most common outcome in adulthood is desistance of GID with a homosexual sexual orientation (e.g., Green, 1987). Some have interpreted this finding to mean that the cross-gender behaviors observed in children with GID is simply an early manifestation of later homosexuality (e.g., Minter, 1999) and, therefore, should not be pathologized or treated (e.g., Corbett, 1998; Isay, 1997). However, cross-gender behaviors in childhood are not isomorphic with a later homosexual sexual orientation. Some boys with GID grow up to have a later heterosexual sexual orientation (e.g., Green, 1987; Wallien & Cohen-Kettenis, 2008). A second response to this particular criticism is that what constitutes a mental disorder is its operational definition (Green, 2011). Thus, if a child meets diagnostic criteria for a disorder, it is irrelevant to the assignment of a current diagnosis whether the child will meet the diagnosis in the future.

As discussed above, GID is a controversial diagnosis. The diagnosis itself has received much criticism and there remains a significant lack of consensus in the field regarding clinical management of the disorder. Discussions and debates on best treatment practices have raised the issue of the long-term outcomes for boys with GID, particularly in regard to gender identity and sexual orientation (e.g., Zucker, 2008b), a topic now addressed in the present literature review.

1.7 Psychosexual Outcome of Boys with GID

One approach to understanding the developmental trajectory of boys with GID is to retrospectively assess the childhood experiences of adult male-to-female transsexuals. These studies have found that adolescents and adults with GID, particularly those with a co-occurring homosexual sexual orientation (in relation to their birth sex), invariably recall a pattern of childhood cross-gender behavior that corresponds to the DSM criteria for GID (Green, 1974; Smith, van Goozen, Kuiper, & Cohen-Kettenis, 2005; Zucker et al., 2006). However, given the potential problems with retrospective research (for an overview, see Hardt & Rutter, 2004), most notably that the recollections may not be accurate, the ideal methodology to understand the long-term outcome of boys with GID is to identify a group of such children and follow them prospectively. Since the 1960s, a number of such studies have been conducted. Of these, Green’s (1987) study and Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis’ (2008) study constitute the two most comprehensive long-term follow-up of boys with GID. In addition, the results of 6 other follow-up studies which utilized much smaller sample sizes are also summarized. For clarity, the results on gender identity outcome are presented first followed by the results on sexual orientation outcome. Across all studies, sexual orientation is classified in relation to birth sex.

1.7.1 Gender Identity Outcome of Children with GID

Zucker and Bradley (1995) summarized data from six published follow-up studies of

boys who displayed marked cross-gender behavior (Bakwin, 1968; Davenport, 1986; Kosky, 1987; Lebovitz, 1972; Money & Russo, 1979; Zuger, 1978). The results of these studies are presented as a group due to the small sample size of each study. Across these six studies, a total of 55 boys were seen at follow-up (range, 16-36 years). Of these, 5 (9.1%) were classified as transsexual at follow-up (i.e., they showed persistent gender dysphoria). All 5 persisters had a homosexual sexual orientation.

One of the earliest prospective follow-up studies to utilize a reasonably large sample size was conducted by Green (1987). Green’s sample consisted of 66 behaviorally “feminine”[3] boys and 56 control boys[4] who were unselected for their gender identity. Both groups of boys were initially assessed at a mean age of 7 years (range, 4-12 years) and were recruited through various forms of advertisement. Although Green did not utilize a formal DSM diagnosis,[5] from his clinical descriptions it appears that most of the behaviorally feminine boys would have met criteria for GID. Most of the feminine boys stated their wish to be girls or to grow up to be women, avoided male-typical activities (e.g., rough-and-tumble play, sports), preferred female roles in pretend play, and showed a preference for girls’ clothes, toys, and peers (Green, 1974, 1976). Forty-four feminine boys and 35 control boys were available for follow-up assessment in adolescence and adulthood (M age, 18.9 years; range, 14-24). Only a minority of the feminine boys (n = 12) received formal therapy between the childhood assessment and the follow-up interview. At follow-up, only one (2.3%) of the 44 behaviorally feminine boys continued to experience gender dysphoria and desired sex reassignment surgery. None of the control boys reported any gender dysphoria.

More recently, Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis (2008) conducted the largest follow-up study to date on boys and girls with GID (77 children; 59 boys, 18 girls). The childhood data were collected as part of the standard assessment of children seen in their specialized gender identity clinic in The Netherlands. At follow-up, 54 participants (40 boys, 14 girls) were successfully traced and completed the follow-up assessment. The remaining 23 participants (19 boys, 4 girls) could not be traced. However, Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis assumed that these untraced participants were desisters on the premise that had they been persisters they would have likely had contact with the clinic and, therefore, included them in the calculation of a persistence rate. Of the 77 children followed prospectively, Wallien and Cohen-Kettenis reported that 21 (12 boys, 9 girls) were still gender dysphoric at follow-up, which yielded a persistence rate of 27% for the total sample of boys and girls with GID. However, when calculated based only on those participants who were actively involved in the follow-up assessment (i.e., excluding the 23 participants who could not be traced at follow-up), the persistence rate was 38.8%.[6]