Despite the current rhetoric. . .

. about sex and intimacy’s involving more than penile-vaginal intercourse,

the quest for a rigid erection

appears to dominate both popular and professional interest. Moreover,

it seems likely that our

diligence in finding new ways for overcoming erectile difficulties serves

unwittingly to reinforce the male

myth that rock-hard, ever-available phalluses are a necessary component

of male identity. This is indeed

a dilemma.

Rosen and Leiblum,

19921

General Considerations

The Problem

A 49-year-old widower described erection

difficulties for the past year. His 25-year

marriage was loving and harmonious

throughout but sexual activity stopped after

his wife was diagnosed with ovarian cancer

six years before her death. Their sexual

relationship during the period of her

illness had been meager as a result of her lack

of sexual desire. Although he missed her

greatly, he felt lonely since her death

three years before and, somewhat

reluctantly at first, began dating other women. A

resumption of sexual activity soon resulted

but much to his chagrin he found that

in contrast to when he would awaken in the

morning or masturbate, his erections

with women partners were much less firm. He

felt considerable tension, particularly

because some months before, he had

developed a strong attachment to one

woman in particular and was fearful that

the relationship would soon end because

of his sexual troubles. As he discussed his

grief over the loss of his wife and talked

about his guilt over his intimacy with

another woman, his erectile problems began

to diminish.

A 67-year-old man, married for 39 years,

and having a history of angina prior to a

coronary by-pass operation three years

before was referred to a “sex clinic” together

with his wife because of his erectile

difficulties. Sexual experiences had been enjoyable

and uncomplicated for both until he

developed angina at the age of 62.

Orgasm provoked his chest pain.

Nitroglycerin was prescribed but he used it only

occasionally because it resulted in

headache. His angina during sexual activity was

frightening to his wife who, nevertheless,

recognized the importance of sexual

experiences in his life and supported his

desire to continue being sexually active.

Cardiac surgery resulted in the

disappearance of his chest pain. However, some

months before his operation, he began to

experience difficulty becoming fully

erect at any time, and would frequently

lose whatever fullness he had before vaginal

entry occurred. His erectile difficulties

with his wife had become persistent

and when questioned, it was apparent that

his morning erections were not different.

Sildenafil (Viagra) was dismissed as a

treatment possibility because of his occasional

use of nitroglycerin. He was referred to a

urologist for intracavernosal injections.

Terminology

The phrase “erectile dysfunction”

has provided competition for the more popular word

“impotence.” The latter has a

tenacity for usage that does not exist for the female

equivalent and now rarely-seen

word, “frigidity.” Both words have similar deficiencies:

they are so broad in usage they

(1) incorporate disorders of desire and function and

(2) imply something pejorative

about the patient’s personality quite apart from their

sexual expression.2

The social confusion surrounding

the word “impotence” is, perhaps, exemplified by

the first recommendation of the

National Institutes of Health Consensus Statement on

Impotence, which was to change

the term impotence to erectile dysfunction as a way of

characterizing “the inability to

attain and/or maintain penile erection sufficient for satisfactory

sexual performance.”3

(Interestingly, no conference was necessary to change

usage of the word “frigidity”).

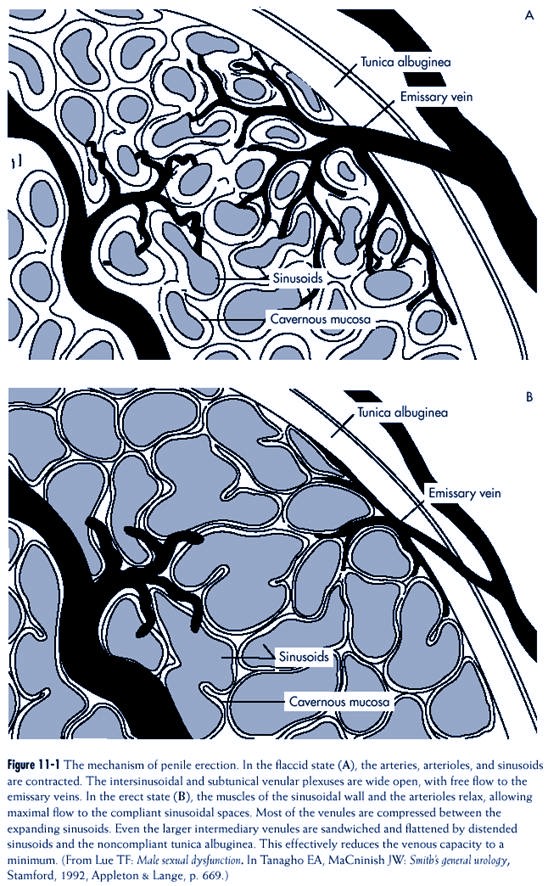

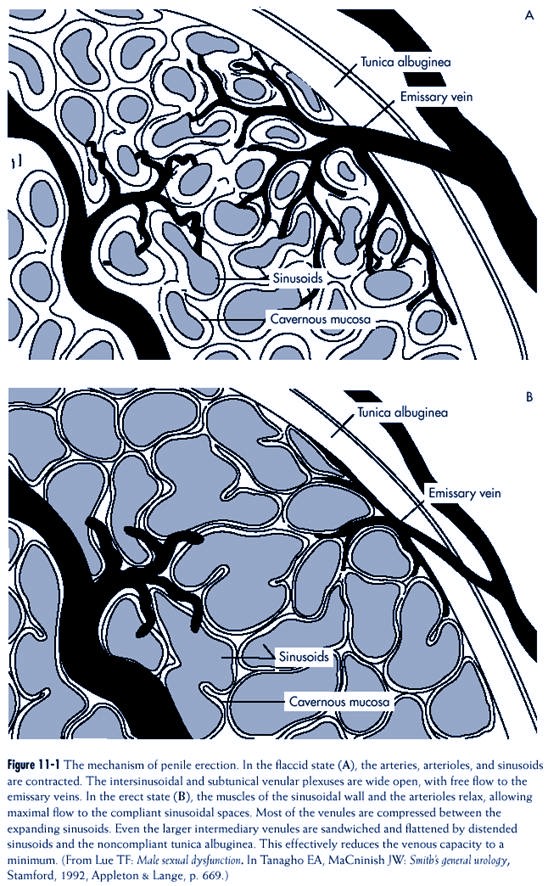

Mechanism of Erection

The fundamental element in the

development of an erection is the trapping of blood

in the penis. The mechanism by

which this occurs was described by Lue and Tanagho

(Figure 11-1). A human penis has

three cylinders: Paired corpora cavernosa (CC) on

the dorsal surface, and the completely

separate corpus spongiosum (CS), which carries

the urethra and is responsible

for the ventral bulge.

The CS anatomically includes the

glans of the penis. The CC are each surrounded

by an inflexible envelope of

fibrous tissue: the tunica albuginea (TA). The CS has a

much thinner TA and is connected

to the glans, which has almost none.

Blood is carried to the penis by

the two internal pudendal arteries

and within the penis by paired

cavernosal arteries. The latter subsequently

divide into smaller vessels

(arterioles), which are surrounded

by smooth muscle. The same can be

said of the helicine arteries (small

spiral shaped arteries). In the

CC and CS, blood is then carried to

interconnecting sinusoids

(microlakes, which have the appearance of a

sponge when filled but are mostly

collapsed when a penis is flaccid),

which are also surrounded by

smooth muscle. Small veins (venules)

carry blood away to the emissary

veins, which in turn pierce the TA.

As an erection develops, there is

relaxation of the smooth muscle

around the arterial tree and

walls of the sinusoids, increasing the inflow

As an erection develops, the smooth

muscle around the arterial tree and

walls of the sinusoids relaxes, increasing

the inflow of blood into the penis and

allowing more blood to remain. While

expansion occurs, the venules are

compressed

between the sinusoids and TA,

thereby stopping the outflow and in

effect trapping blood in the sinusoids of

the penis.

|

of blood into the penis and

allowing more blood to remain. While expansion occurs,

the venules are compressed

between the sinusoids and TA, thereby stopping the outflow

and in effect trapping blood in

the sinusoids of the penis. “The smooth muscles

in the arteriolar wall and

trabeculae surrounding the sinusoids are the controlling

mechanism of penile erection.”4

(Biochemical aspects of erection

are discussed in the treatment section of “ Generalized

Erectile Dysfunction: Organic,

Mixed, or Undetermined Origin” below in this

chapter).

Definition

The main difficulty with the

definition of erectile dysfunction is whether the diagnosis

of erectile problems should refer

only to the hardness or softness of a man’s erection

or if it should also include a

behavioral component. For example, should a man

who has erections that are

persistently partial but whose penis is sufficiently enlarged

to regularly engage in

intercourse be designated as having an “erectile disorder?” If

that same man designates himself

as “impotent,” what should be the diagnostic position

of the health professional?

Should there be a subjective component to an erectile

disorder: does it make any

difference what the man (or his partner) thinks? Is the

fullness of a man’s penis in

intercourse all that matters? Is intercourse the only sexual

activity on which the definition

is based? What about erections with other sexual

practices? These, and other

questions, are not intellectual exercises but daily clinical

quandaries.

Classification

DSM-IV-PC summarized the criteria

for the diagnosis of “Male Erectile

Disorder” as follows: “persistent

or recurrent inability to attain, or to

maintain until completion of the

sexual activity, an adequate erection,

causing marked distress or

interpersonal difficulty”5(p. 116).

The clinician

is further instructed to

“especially consider problems due to a general

medical condition . . . such as

diabetes or vascular disease, and

problems due to substance use . .

. such as alcohol and prescription

medication. Erectile

dysfunction in all situations, as well as lack of nocturnal erections,

strongly suggests

that a general medical condition

or substance use is the cause”(italics added).

The subclassification of Erectile

Disorders used in this chapter is summarized in

Figure 11-2.

Epidemiology

The Massachusetts Male Aging

Study (MMAS) provided revealing information about

erectile function, dysfunction,

and “potency” in middle-aged and older men.6 The

study was conducted in the late

80s, was concerned with health and aging in men, was

community-based, and involved a

random sample of noninstitutionalized men 40 to 70

years old. Individuals who

completed a self-administered questionnaire on sexual function

and activity included 1290 (75%)

of the 1709 MMAS subjects. “Potency” was

subjective in that it was defined

by those who completed the questionnaires. Defined

as “satisfactory functional

capacity for erection,” “potency” could “coexist with some

Erectile dysfunction in all situations,

including the lack of nocturnal erections,

strongly suggests that a general medical

condition or substance use is the cause.5

|

degree of erectile dysfunction in

the sense of submaximal rigidity or submaximal capability

to sustain the erection.” Four

degrees of “impotence” were described:

• None

• Minimal

• Moderate

• Complete

The overall prevalence of

impotence in this study was found to be

52%, with 15% defined as minimal,

25% moderate, and 10% complete.

Prevalence was highly related to

age with the probability of moderate

impotence doubling from 17% to

34% and complete impotence tripling

from 5% to 15% between subject

ages 40 to 70 years. Looking at

this from the opposite

perspective, 60% of men were not impotent at

age 40 years, compared to 33% not

impotent at age 70 years.

The frequency of erectile

problems found in health care settings seems to depend

somewhat on the clinical context.

That is, different percentages can be found in

various clinical settings:

medical outpatients, urology, and sex therapy7 (p.

11). In a

review of the frequency of sexual

problems presented to “sex clinics” between the

mid-70s to 1990, 36% to 53% of

men complained of “male erectile disorder.”8 Masters

and Johnson subcategorized this

diagnosis into “primary” and “secondary”.9 The

former referred to a man who had

never had intercourse (p. 137), and the latter

referred to a man who had been

able to have intercourse at least once in the past

Sixty percent of men were not impotent

at age 40 compared to 33% not impotent

at age 70 years.

|

(p.157). Of all the men with

“impotence” who consulted Masters & Johnson, 13%

had the primary form (p. 367).

Etiology

“Repeatedly bandied about is the

hackneyed declaration that in the 1970s, mental

health professionals pronounced

90% of impotence to be psychogenic; more recently

urologists proclaim that 90% of

impotence is organic. Both sides are wrong, not just

for the disrespectful attitudes

toward one another, but for failing to develop more

sophisticated notions of

etiology.”10

LoPiccolo saw clinical

limitations to the either/or approach and suggested an

alternative way of thinking about

the etiology of erectile dysfunctions: that organic

and psychogenic factors be viewed

as two “separate and independently varying

dimensions” and that both should

be examined in each instance.11 To

support this

position, he reported on 63 men

with erectile difficulties who were carefully and

thoroughly investigated in both

areas. Ten men were found to have a purely psychogenic

etiology, and three men were

found to have a purely organic etiology.

The majority of men in this study

(50/63) displayed a mixture of factors, indicating

that a “two-category typology was

. . . inappropriate.” Furthermore, almost

one third of the men (19/63) had

“mild organic impairments” but “significant psychological

problems.” These men might have

been considered “organic” in a twopart

etiological scheme, however, they

might also have been sufficiently responsive

to psychological intervention

such that physical treatment may not have been necessary.

In a diagnostic and a therapeutic

sense, the implication of LoPiccolo’s approach is

quite serious. It means that even

if a factor that is of potential etiological significance is

found (biological or

psychological), it is not necessarily the factor. Or, in other words,

“the detection of some possible

etiological factor . . . does not mean that the

cause . . . has been fully

explained. Such a factor may even be coincidental, of no

(actual) etiological

significance.”12

The possible nature of the

interrelationship between biological and psychological

factors was suggested as the

following: “When any one (organic factor) occurs in isolation,

it may serve to make erections

more vulnerable to emotional disturbances and

sympathetic overactivity,

facilitating the vicious circle of performance anxiety that

maintains ED.”12

Investigation

History

History-taking is an

indispensable element in the investigation of erectile disorders

and provides direction for

further exploration and treatment. Issues to inquire about

and questions to ask include:

1. Duration (see Chapter 4,

“lifelong versus acquired”)

Suggested Question: “Have you

always had difficulties with erections

or is this a relatively new

problem?”

2. Partner-related erections (see

Chapter 4, “generalized” versus “situational”)

Suggested Question: “What are

your erections like when you are

with your wife (partner)?”

3. Sleep [including morning]

erections (see Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “What are

your erections like when you

wake up in the morning?”

Additional Question: “Do you

wake up at night for any reason?”

Additional Question if the Answer

is Yes: “What are your erections like

when you wake up at night?”

(Comment: the assessment value of

asking about sleep-related erections is generally

recognized but not universally

accepted.13 When full sleep-related erections exist, the

information seems highly useful

from a diagnostic viewpoint. However, partial or nonexistent

sleep erections are not

necessarily meaningful since this situation may coexist

with daytime erections firm

enough for intercourse.)

4. Masturbation erections (see

Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “What are

your erections like when you stimulate

yourself (or masturbate)?”

5. Fullness of erections (see

Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “On a

scale of zero to ten where zero is

entirely soft and ten is fully

hard and stiff, what are your

erections like when you are with

your wife (partner)?”

Additional Question: “Using

the same scale, What are your erections

like when you wake up in the

morning?”

Additional Question: “If you

wake up during the night, using the

same scale, what are your

erections like at that time?”

Additional Question: “using

the same scale, What are your erections

like with self-stimulation

or masturbation?”

Additional Question Under All

Three Circumstances: “About how long do

your erections LAST?”

(Comment: Even though erections

may be full under all three circumstances, the duration

of erections may be important.

Erections may consistently be short-lived—a matter

of diagnostic significance, since

that observation may indicate a “venous leak”).13

6. Psychological accompaniment

(see Chapter 4, “patient and partner’s reaction to

problem”)

Suggested Question: “When you

have trouble with your erection,

what’s going through your mind?”

Additional Question: “What

does your wife (partner) say

at these times?”

Physical Examination

In men with erectile

difficulties, physical examination is essential even

if the “yield is low.”12

“Without it many patients feel that they have not

been properly assessed or taken

seriously and they may refuse a psychogenic

diagnosis as a result”.12

The physical examination concentrates

particularly on the endocrine,

vascular and neurologic systems,

as well as local genital factors.

Signs of hormonal abnormalities

include the following14 (p. 85):

1. Testicular atrophy

2. Gynecomastia

3. Galactorrhea

4. Visual field abnormalities

5. Sparse body hair

6. Decreased beard growth

7. Skin hyperpigmentation

8. Signs of thyroid abnormalities

9. Low energy level and lack of

“well-being”

Signs of vascular disease include

the following14 (p.91):

1. Weak pulses in legs or ankles

2. Hair loss on lower legs

3. Unusually cool temperature of

penis or lower legs

4. High lipid levels

5. High cholesterol levels

6. Duputyren’s contractures

[Peyronie’s disease only]

7. Fibrosis of outer ear

cartilage [Peyronie’s disease only]

Signs that indicate neurological

factors include the following14 (p. 93):

1. Weak or absent genital

reflexes (bulbocavernosus, cremasteric, scrotal, internal

anal, and superficial anal)

In men with erectile difficulties, physical

examination is essential even if the

“yield is low.”12 Many

patients feel that

they have not been properly assessed or

taken seriously if there is no physical

examination, and they may refuse a

psychogenic diagnosis as a result.12

2. Neurological abnormalities in

the S2 to S4 nerve root distribution

3. Reduced penile sensory

thresholds to light touch electrical stimulation or

vibration

An investigation conducted in a medical

outpatient clinic found that the physical

examination rarely helped to

differentiate various etiological factors with two exceptions15:

• Small testes in patients with

primary hypogonadism

• Peripheral neuropathy in

patients with diabetes

Laboratory Investigation

The extent of a clinician’s use

of the laboratory in the investigation of erectile dysfunction

depends on the results of the

history and physical examination (see “Investigation”

below in this Chapter in the

sections on “Situational [‘psychogenic’] Erectile Dysfunction”

and “Generalized Erectile

Dysfunction: Organic, Mixed, or Undetermined Origin.”

Treatment

As LoPiccolo has shown,

psychological and physiological factors are

present in the vast majority of

men with an erectile disorder.11 “Psychological”

factors include social, cultural,

religious, and interpersonal

elements, and those within the

person. Since all sexual behavior of men

is influenced to a great degree

by these issues, it is reasonable to

assume that these factors are

present in the context of erectile difficulties

as well. The logical result of

LoPiccolo’s research is the concept

that regardless of the etiology

of a man’s erectile difficulties, a health care clinician

must always attend to universally

concomitant psychological issues. That is:

“Given the critical role of

psychological factors, even in cases with clearcut organic

etiology, the failure to

attend to psychological issues is indefensible (italics added). The

potential

impact of erectile difficulties

on mood state, self-esteem and self-efficacy, as well as on

the couple’s relationship cannot

be overemphasized.”16

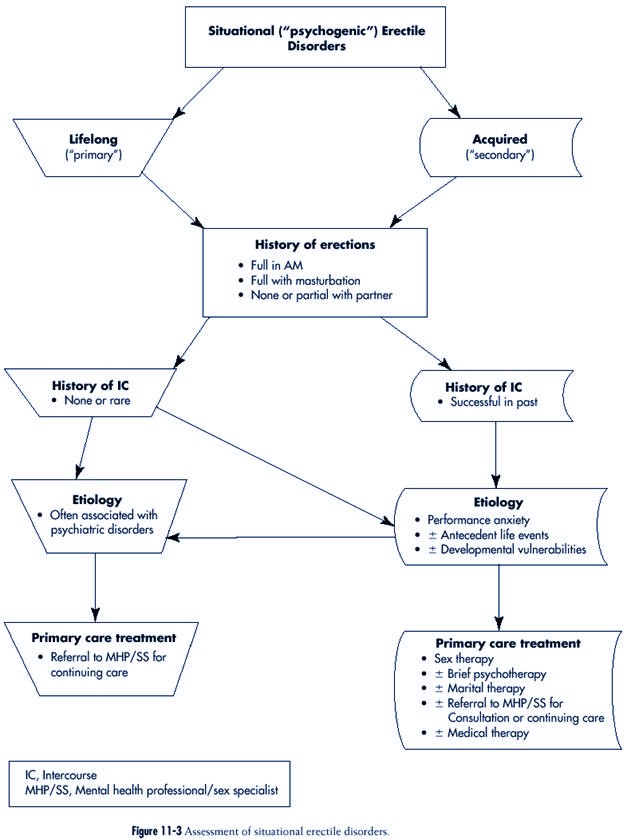

Situational (“Psychogenic”) Erectile Dysfunction

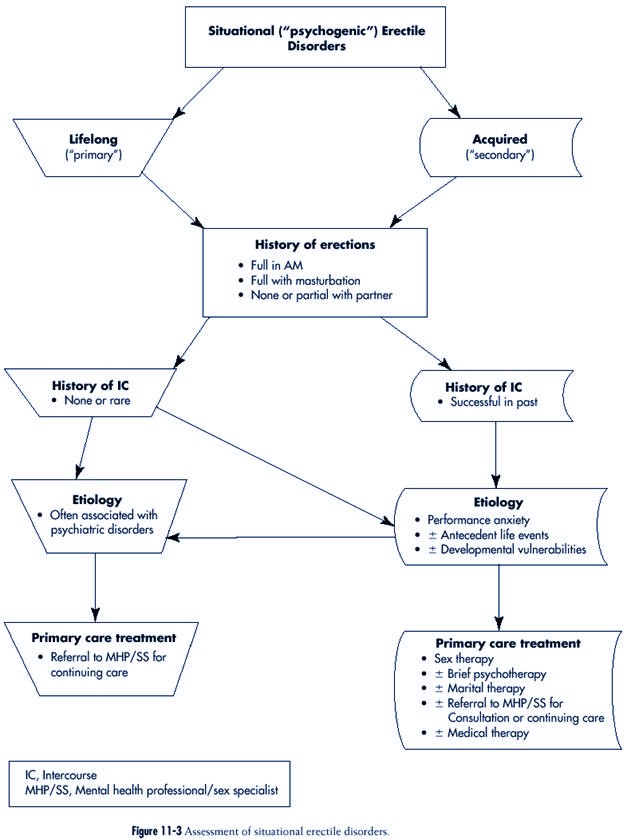

The assessment of situational

erectile disorders is summarized in Figure 11-3.

Description

Lifelong (“Primary”) Erectile Disorders

In this unusual syndrome, the man

reveals that all, or most, attempts at intercourse

result in diminution of his

erection before attempts at vaginal entry. Levine reasonably

suggested that the definition of

the disorder be “liberalized” to include men who

gain vaginal entry “occasionally”17

(p. 208), Typically, the man has no difficulty

obtaining full erections when

alone, with masturbation, or when awakening. Ejaculation

and orgasm have been similarly

unimpaired. The sexual desire phase may have

been problematic if thoughts

associated with sexual arousal were atypical (as is

Failure to attend to psychological issues

is indefensible. The potential effect of

erectile difficulties on mood state,

selfesteem,

and self-efficacy (as well as the

couple’s relationship) cannot be

overemphasized.16

often the case), such as

fantasies related to paraphilias. Since behavior connected to

such fantasies is often easier to

carry out alone, such men tend to avoid intimate

relationships and may depend on

prostitutes (with whom they can be more candid)

for partner-related sexual

experiences. Even then, intercourse rarely, if ever, occurs.

Pressure from a (non-prostitute)

partner may be a major factor in seeking treatment.

When this occurs, the patient may

not be particularly forthcoming about his thoughts

and feelings.

A 32-year-old man was seen with his

29-year-old wife. They were married for two

years and despite being sexually active

with one another several times each week,

intercourse never occurred. (They

previously agreed not to engage in intercourse

before they married.) She was aware of the

fact that he had never experienced

intercourse in the past. His erection

predictably diminished whenever he moved

close to her vagina. She wanted to become

pregnant and felt the “biological clock

ticking.”

Her desire for pregnancy and her love for

her husband resulted in a singleminded

pursuit of her attempts at solving their

sexual difficulties. He was less

enthusiastic. Attempts at psychotherapy

with him alone and sex therapy as a

couple proved unhelpful. Since he was a shy

person and spontaneously revealed

little about himself, he never previously

told anyone about having been repeatedly

sexually assaulted as a child by his mother.

Nor had he ever discussed his

current sexual fantasies (about which he

was quite ashamed) that involved the

insertion of a knife into a woman’s vagina.

He was again referred for individual

psychotherapy and accepted the need for

candor with his therapist concerning

his sexual experiences as a child and his

current sexual thoughts and feelings.

Acquired (“Secondary”) Erectile Disorders

In contrast to the lifelong form

of situational erectile dysfunction, the patient

reports having had intercourse in

the past, perhaps on many occasions for many

years. However in the present,

full erections might occur with his partner before

clothes are removed but the

fullness may diminish after he reaches the bed or

after the commencement of sexual

activity. Intercourse might occur sometimes but

this seems unpredictable.

Characteristically, he never had a problem obtaining full

erections after a period of sleep

and with masturbation and, as well, describes no

difficulty with ejaculation and

orgasm now or in the past. History reveals that

when younger, he frequently had

erection troubles with partners on the first few

occasions when sexual intercourse

was attempted. However, when in a long-term

relationship, he functioned well

sexually although erectile difficulties occasionally

reappeared at times of “stress.”

After a relationship of many years, doubts about

his sexual “performance”

developed. There may have been a marked diminution of

sexual activity in spite of his

partner’s attempts at reassurance. She believed him

not to be sexually interested,

and wondered about her own attractiveness to him.

Questioning revealed that his

apparent sexual disinterest is actually avoidance. He

remains privately interested but

feels that he is not “a man” anymore with his

wife.

A 51-year-old rather shy man was seen

together with his 49-year-old outspoken

wife. They were married for 23 years.

Sexual activity had never been a problem

until about five years ago when his

erections sometimes became soft after vaginal

entry, so much so that intercourse could

not continue. This sequence of events,

and erectile loss even before intromission,

gradually occurred more often and

culminated in the complete lack of

intercourse in the previous six months. His

sexual desire, while never as strong as

that of his wife, had not changed and he

would masturbate (without erectile problem)

and ejaculate about once or twice

each month. He thought that the origin of

his erection troubles were mainly

related to his age but he also wondered if

his substantial use of alcohol for the

previous 25 years was also a factor. His

heavy drinking stopped completely about

five years ago when he joined AA. This was

about the same time that his erection

problems began. After discussion of

possible etiological factors, he understood

that much of his erectile difficulty was

connected to his feelings about his wife.

They were referred to a treatment program

that focused on both their marriage

and their sexual relationship.

Etiology

Lifelong (“Primary”) Erectile Dysfunction

This syndrome is “often, though

not invariably, associated with a diagnosable major

[psychiatric] condition”18

(p. 133). Masters and Johnson described a group of 31

men with “Primary Impotence,”

eleven of whom were in unconsummated marriages9

(pp. 137-156). Factors they

considered to be of etiological significance were multiple

and included the following:

1. Homoerotic desire

2. Mother/son incest

3. Strict religious orthodoxy

4. Psychologically damaging

attempts at first intercourse with a prostitute (sometimes

associated with drugs or alcohol)

Other investigators also reported

associated paraphilias and gender

identity disorders18

(pp. 133-135);19 (p. 245).

Acquired (“Secondary”) Erectile Dysfunction

Most men with a clearly

situational erectile dysfunction also indicate

that it is acquired.

In almost all such men, the

etiology involves some combination of

factors17(p.

200) in the following three areas:

1. Performance anxiety

In almost all men with acquired erectile

dysfunction, the etiology involves a

combination of factors17

in three areas:

1. Performance anxiety

2. Antecedent life events

3. Developmental vulnerabilities

|

2. Antecedent life events

3. Developmental vulnerabilities

The “phase of time” for each of

these three is, respectively, here-andnow

lovemaking, months to years

(“recent” history), and childhood/

adolescence (“remote” history).

A major here-and-now issue is

“performance anxiety,” a concept

introduced by Masters and Johnson

to describe the worry that a patient

may have about his or her sexual

function and whether it will be similarly

impaired on a current occasion as

it was at a previous time.9 Performance

anxiety is partner related and

probably universal in men with

erectile difficulties. From a

primary care perspective, performance anxiety

is an important target of the

treatment of “psychogenic impotence”

in both solo men and couples.

However, this component explains only

part of the etiology of this

syndrome, since eliminating performance

anxiety does not always result in

cure.

Antecedent life events and

developmental vulnerabilities may be of

therapeutic significance also,

but they are difficult to consider in detail

in a primary care setting.

The former “typically fall into

one of five categories”17 (p.202):

1. Deterioration in the nonsexual

relationship with a spouse or

partner

2. Divorce

3. Death of a spouse

4. Vocational failure

5. Loss of health

Developmental vulnerabilities

include such issues as child sexual abuse and impairments

in sexual identity.17

On a clinical level, one

frequently has the impression of a link between psychogenic

erection difficulties and

difficulty with expression of anger. In the MMAS study,

the suppression and expression of

anger was assessed. “Men with maximum levels of

anger suppression and anger

expression showed an age-adjusted probability of 35%

for moderate impotence and 16% to

19% for complete impotence, both well above

the general level (9.6%).”6

The MMAS study did not subcategorize men with “impotence”

according to whether the origin was

“psychogenic,” “organic,” mixed,” or

“undetermined.” It may certainly

be possible that problems with anger may also

potentiate some of the

etiological factors associated with erectile difficulties of

organic, mixed or undetermined

origin discussed below.

Laboratory Investigation

If in instances where the man

reports being otherwise healthy, the history clearly

indicates the situational nature

of the man’s erectile dysfunction, there is no sign of

any contributory physical

abnormality, and there are no other sexual symptoms (such

as lack of sexual desire), little

needs to be done to obtain additional specific laboratory

data.

Performance anxiety is partner related

and probably universal in men with

erectile difficulties.

Developmental vulnerabilities include

child sexual abuse and impairments in

sexual identity.17

Antecedent life events typically fall into

one of five categories17:

1. Deterioration in the nonsexual

relationship

2. Divorce

3. Death of a spouse

4. Vocational failure

5. Loss of health

Eliminating performance anxiety does

not always result in cure.

|

Treatment

“It is fortunate for many

psychologically impotent men that a complete

understanding of the causes is

not necessary. Some men spontaneously

get over their problem within a

short period of time without

any therapy”17

(p. 202). For those whose problem is not solved,

an approach is proposed that

concentrates on five themes that have

been identified in a review of

the literature (Box 11-1).16 Most

importantly for generalist health

professionals, some of these five

themes listed in Box 11-1 can be

easily integrated into primary

care.

The first theme is accurate

information and realistic ideas and expectations regarding

sexual performance and

satisfaction—all of which is a problem in many

men with erectile difficulties

(and their women partners).

Areas to be addressed include:

1. Genital anatomy and physiology

2. The sex response cycle

3. Masturbation

4. Male-female differences in

sexual response

5. Effect of aging, illness, and

medication on sexual desire, arousal, and

orgasm

Comprehensive, inexpensive, and

up-to-date self-help books are easilly

vailable and can be used as an

adjunct in this education process.20 The

provision of information can

correct unrealistic ideas and expectations—

thoughts that could, themselves,

significantly interfere with erectile function.

For example, the “gold standard”

of erectile function for many men is what occurred in

their teenage years. The folly of

“living in the past” becomes evident to a man in his

(for example) 40s when he is

asked to provide another example of a part of his body

that functions in the present as

it did when he was a teenager. In addition, it could be

pointed out to him that he is, in

effect, basing his sexual expectations for his 60 years

of adult sexual function

(approximate life expectancy minus 15 years of pre- and early

Box 11-1

Themes in the Treatment of Situational (“Psychogenic”) Erectile

Dysfunction

• INFORMATION, including realistic ideas

and expectations concerning sexual performance

and satisfaction

• PERFORMANCE ANXIETY RELIEF through use of

“sensate focus”

• ”SCRIPT” MODIFICATION (‘who does what to

whom’)

• ATTENTION TO RELATIONSHIP ISSUES (e.g.,

intimacy, control, conflict resolution,

trust)

• RELAPSE PREVENTION

|

Areas to be addressed include:

1. Genital anatomy and physiology

2. The sex response cycle

3. Masturbation

4. Male-female differences in sexual

response

5. Effects of aging, illness, and

medication

on sexual desire, arousal, and

orgasm

Easily-available, comprehensible and

comprehensive, inexpensive, and up-todate

self-help books can be used as an

adjunct in this educational process.20

The “gold standard” of erectile function

for many men is what occurred in their

teenage years. The folly of “living in the

past” becomes evident to a man in his

(for example) 40s when he is asked to

provide another example of a part of

his body that functions in the present as

it did when he was a teenager.

|

adolescence) on the five (or so)

years of erectile experience as a teen! Other examples

of ideas and expectations that

might be discussed with a patient include his thoughts

when he or his partner is

initiating sexual activity and when his penis is becoming

firmer or softer.

Yet another example of the

therapeutic value of information is that of the sexual

changes associated with aging.

The educational effect on the treatment of erectile

dysfunction was studied in a

group of heterosexual couples between the ages of 55 and

75.21 Investigators

found that a four-hour workshop resulted in increased knowledge,

especially about the normal

changes that occur with age, thereby allowing participants

to have more realistic

expectations of themselves and their partners. Sexual satisfaction

also increased despite the

presence of associated organic factors.

The second theme is the relief of

“performance anxiety.” Diminishing or eliminating this

frequently appearing factor

involves inducing sexual response in the man (in this

instance, erection) while he

paradoxically avoids sexual invitations for intercourse.

Masters and Johnson described

this approach to the treatment of performance anxiety9

(pp. 193-213). The method

involves couple oriented touching “exercises” and

concentrates on sensate focus,

a term they coined (pp. 71-75) to denote a focus on

immediate sensation rather than

sexual goals of, for example, intercourse. Briefly, the

exercises occur in stages and

initially exclude intercourse and touching of breasts (in

the woman) and genitalia, then

include touching of the previously barred areas (while

maintaining the exclusion of

intercourse), and finally include unrestricted touching

and intercourse. Couples do not

move to the next level of the exercise until the previous

one is mastered. While requiring

repeated visits, this technique

is not complex and might,

therefore, be within the boundaries of primary

care (depending on the

clinician’s time, comfort, and interest

and the availability of

specialists to whom one could refer).

One major (and often unappreciated)

objective of “sensate focus” in

the treatment of erectile

dysfunction is change in the communication

pattern between partners so they

could, with “permission” (i.e., encouragement),

and with a minimum of tension and

embarrassment, tell one

another what is, and is not,

pleasurable. (Rather than the communication exercise it is,

sensate focus is sometimes

mistakenly thought of as a way of allowing one to discover

previously unappreciated physical

feelings in particular body areas.) A second objective

of “sensate focus” is to remove

the demand for intercourse. Since the man does not

“need” an erection for any

purpose other than intercourse and intercourse is not to take

place, theoretically the

“pressure” on the man to “perform” will be removed and the

worry (which is thought to

inhibit his erection) will disappear, thus allowing his erection

to develop unhindered.

Two obstacles to sensate focus

have been described11 (p. 189). First, the

passive

process of sensate focus is

contrary to the need of aging men for

active and direct penile

stimulation for an erection to develop. Second,

the idea of performance anxiety

is so popular that general knowledge

of the concept has rendered its

treatment less effective. Consequently,

LoPiccolo coined the term metaperformance

anxiety to explain

Rather than the communication exercise

it is, sensate focus is sometimes

mistakenly

thought of as a way of allowing

one to discover previously unappreciated

physical feelings in particular body

areas.

Functional men can become aroused on

demand, whereas the same request in

dysfunctional men results in interference

with the arousal process.

|

why, on some occasions,

“eliminating performance anxiety does not lead to erection

during sensate focus body

massage”11 (p. 189).

Recently the role of “anxiety” in

producing erectile troubles and the expected relief

with its disappearance has been

reexamined and reviewed from a research rather than

clinical viewpoint.22

Functional and dysfunctional men have been shown to respond

differently to anxiety. The

results of these studies are summarized as follows:

1. Functional men can become

aroused on demand, whereas the same request in

dysfunctional men results in

interference with the arousal process (similar results

were found in laboratory studies)

2. Functional men report their

subjective arousal to be greater than dysfunctional

men regardless of what occurs

physically

3. (Particularly interesting from

a therapeutic viewpoint) functional

men report distraction to be an

obstacle to sexual response, whereas

this is neutral or actually

helpful to dysfunctional men16

The third theme concentrates on

sexual “script” modification (i.e., changes to

what actually occurs sexually

between two people). The fourth theme concentrates on relationship

issues such

as intimacy, control, conflict resolution, and trust. The fifth theme

concentrates

on the prevention of relapse.

Since the third, fourth, and fifth areas are often more

within the interests, practice

pattern, and skills of the sex therapist, they are not discussed

at length here.

Little published information

exists on the treatment of situational erectile dysfunction

by methods usually reserved for

occasions when the etiology is “organic, mixed,

or undetermined” (see below in

the chapter). Few quarrel with the concept of considering

such an approach when

psychologically-oriented methods have been unsuccessful.

However, when medical techniques

are used early in the course of treatment, the concept

is more problematic. The

rationale sometimes given is one of providing the man

an opportunity to have a erection

in worry free circumstances as a way of overcoming

an undefined obstacle. The

rationale continues that after the man

engages in successful sexual

experiences that require an erection he will

be able to do so without extra

support.

A study of the use of

intracavernosal injections in 15 men with “psychogenic

impotence” did not convey a sense

of optimism about the

outcome of such an approach.23

The authors concluded that performance

anxiety was not alleviated, that

dependence on injections for

intercourse remained, and that

the capacity for intimacy did not

improve. One can well imagine

that the consequences (benefits and

disappointments) of the use of

such treatments for men with situational

erectile difficulties become

magnified when men who have these problems

ask for, and are given, an oral

medication such as sildenafil (see below in the

chapter).

Few long-term follow-up studies

have been conducted on the treatment of erectile

dysfunction. Results for

“primary” and “secondary” (i.e., acquired) erectile dysfunction

were reported by Masters and

Johnson as an “overall failure rate” (OFR)

and were based on personal

interviews conducted five years after the patients were

Functional men report distraction to be

an obstacle to sexual response, whereas

this is neutral or actually helpful to

dysfunctional

men.16

A study of the use of intracavernosal

injections in 15 men with “psychogenic

impotence” did not convey a sense of

optimism about the outcome of such an

approach.23 The

authors concluded that

performance anxiety was not alleviated,

that dependence on injections for

intercourse

remained, and that the capacity

for intimacy did not improve.

|

originally treated9

(p. 367). The OFR for “primary impotence” was 41%. This modest

improvement supports the clinical

experience of greater complexity in the treatment

of this form of the erectile

dysfunction syndrome. Furthermore, it suggests

that insofar as “primary”

impotence is concerned, a focus on performance anxiety

without considering other factors

will likely result in quite limited gains.

The OFR reported by Masters and

Johnson for the “secondary” form was 31%.9

Another follow-up study in the

United States, carefully conducted after three years,

found that of the 18 men

presenting with “difficulty achieving or maintaining erection,”

ten maintained the improvement,

four were the same, and three were worse.24

The authors found that there was

“significant improvement maintained across time in

erectile capability during

intercourse . . . . improved satisfaction in the sexual relationship

. . . [and] . . . longer duration

of foreplay.” Hawton and his colleagues

conducted a rigorous one to six

year follow-up study in the United Kingdom and

found that the “gains made during

therapy by couples who presented with erectile

dysfunction were reasonably well

sustained.”25 Of the 18 couples who undertook treatment,

14 reported the problem resolved

or mostly so at the end of therapy, and 11

reported the same at follow-up.

Indications for Referral for Consultation or Continuing

Care by a Specialist

1. Since the “primary” form of

situational erectile disorders is so often associated

with complex individual

diagnosable psychiatric conditions rather than interpersonal

conflicts, referral to a mental

health professional for individual treatment is

usually the most reasonable

course of action19 (p. 245). If the health

professional

is not also a sex-specialist, it

may be useful to consult with one before proceeding

with the referral.

2. Solo men with the “secondary”

form of situational erectile dysfunction (i.e.,

those without a partner, with an

uncommitted partner, in a relationship that is

filled with so much discord that

they are unable to cooperate with each other, or

who have been raised in a culture

in which men are clearly in control and women

entirely submissive) often

require an amalgam of traditional psychotherapy and

sex therapy. Such men are

candidates for individual care with a sex-specialist

who is also a mental health

professional.

3. Couples in which the man has

the “secondary” form of situational erectile dysfunction

and who would benefit by a

here-and-now focus on information and

performance anxiety (previously

described in the treatment of situational problems

in this chapter) could be cared

for in primary care. Couples who do not

respond to this approach may

require an additional focus on two of the other

elements: “script” modification

and attention to relationship conflicts. Given the

time and experience involved in

providing these other components, referral

would be reasonable in these

circumstances. If referral does take place, the health

professional should be a

sex-specialist who also has clinical experience in the

mental health area.

4. Consultation with a

sex-specialist is warrented when consideration is given to

providing a form of treatment

usually reserved for men with erectile dysfunction

of “organic, mixed, or

undetermined origin.” The purpose would be to examine

the possibility of integrating

biological and psychologically oriented treatment

methods.

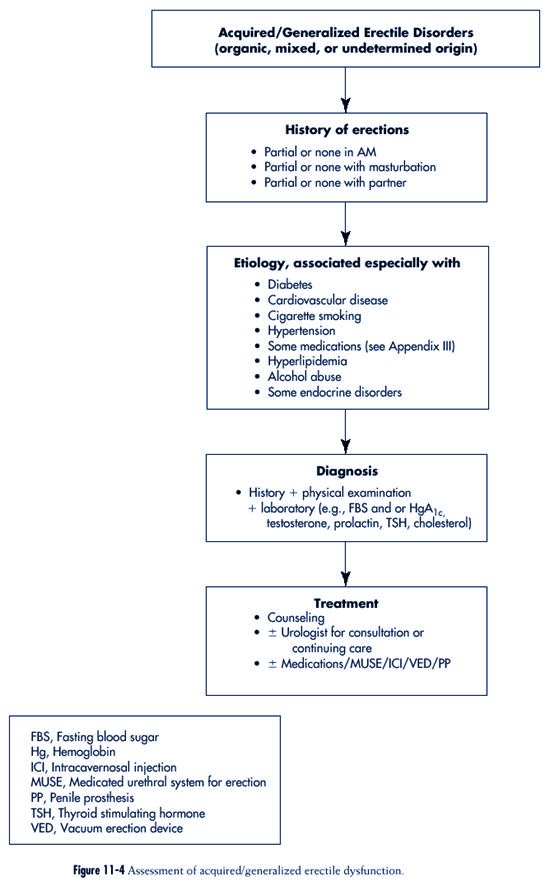

Generalized Erectile

Dysfunction: Organic, Mixed,

or UnDetermined Origin

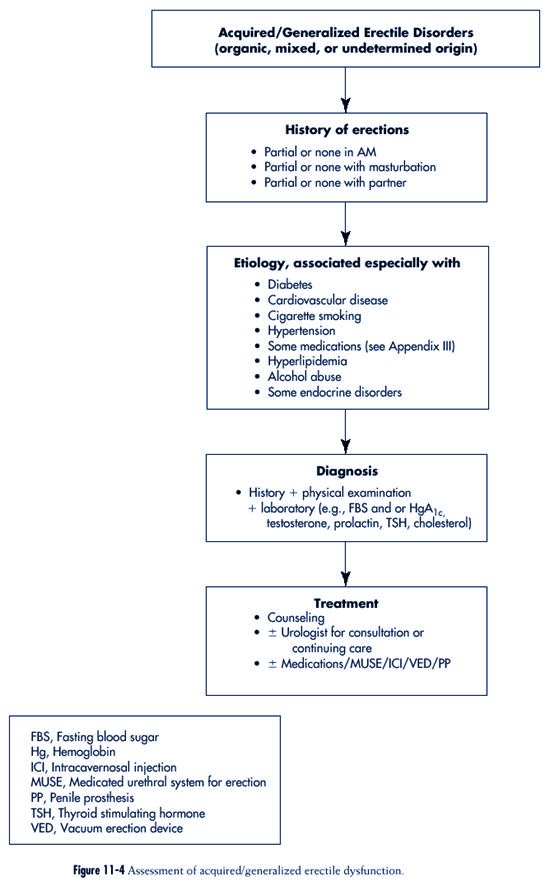

The assessment of generalized

erectile disorders is summarized in Figure

11-4.

Description

The key differentiating feature

of the acquired and generalized form of

erectile dysfunction is that the

difficulty experienced by the man exists

in all major circumstances when

he would be expected to have an erection:

with a partner, masturbation, and

with sleep (including the time

when he awakens in the morning).

In addition, he describes little or no

difficulty with erectile function

in the past. Typically in his 50s or

older, his erection problems

began in recent years. Sexual desire is usually

present but, depending on the

status of his health and the nature of any previous

health troubles, there may have

been problems with ejaculation or orgasm. Relationship

conflict was not apparent except

as a possible result of reluctance to seek help

despite his partner’s

encouragement. Although unhappy, he is not clinically

depressed.

A couple in their mid-60s were seen because

of the man’s erectile difficulties. They

were married for seven years, both for the

second time. Five years before, he held

an executive position in a major computer

software company but as a result of

“downsizing” lost his job and subsequently

retired. His wife had always been in

good health but he had a “mild” heart

attack about three years before. He felt well

since then, stopped smoking, and was not

taking any medications. On his last

medical visit several months earlier, he

talked with his physician about erection

troubles, which had begun about one year

before. Further history-taking revealed

that the fullness of his erections during

sexual activity with his wife (as well as in

the morning and with masturbation—which

occurred once every few months) had

become consistently about 50% of what he

had previously experienced. The last

time he could recall having a full erection

at any time was about one year earlier.

He was referred to a urologist and after a

thorough investigation he was told that

the reason for his trouble was “organic.”

Intracavernosal injections were suggested.

He was reluctant to pursue this option and

wanted a second opinion from a sex

therapist. This consultation primarily

confirmed the opinion of the urologist and as

a result he began injection treatment. He

changed to sildenafil (Viagra) when this

became available and after three months of

use, he and his wife reported that they

were pleased with the results.

The key differentiating feature of the

acquired and generalized form of erectile

dysfunction is that the difficulty

experienced by the man exists in all

major circumstances when he would be

expected to have an erection: with a

partner, masturbation, and with sleep

(including the time when he awakens in

the morning).

|

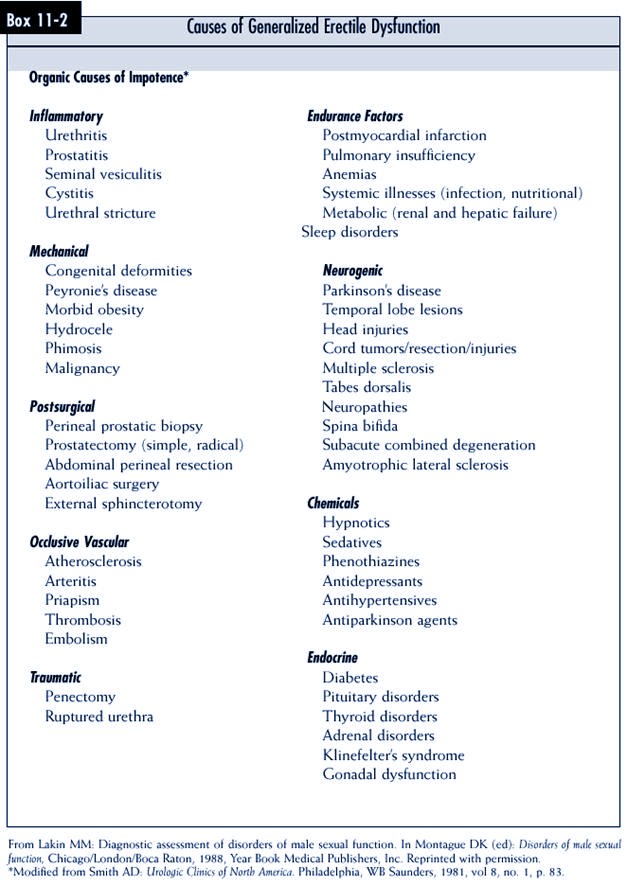

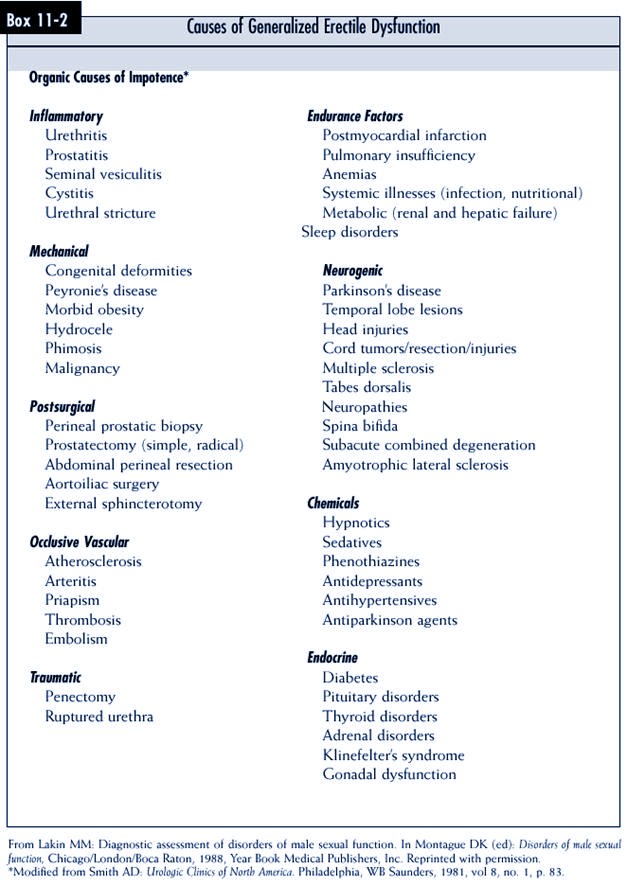

Etiology/Risk Factors

Many medical disorders are

identified as “organic causes” of erection difficulties (see

Box 11-2), however, only a few

seem to account for a great many cases where the

etiology is known. Major

etiological factors are discussed below.

In the Massachusetts Male Aging

Study, health status was ascertained by asking if

diabetes, heart disease, and

hypertension were present.6 These

three “were significantly

associated with changes in the

impotence probability pattern.” After

adjusting for age, 28% of men

with treated diabetes, 39% of men with

treated heart disease, and 15% of

those with treated hypertension were

described as having “complete

impotence.”

Diabetes

Estimates of the prevalence of

erection problems in men with diabetes

range from 27% to 71%.26

As many as 50% of people with type 2

diabetes remain undiagnosed

(about 8 million people in the United

States), a serious situation since

hyperglycemia in this condition

causes microvascular disease and

may contribute or cause macrovascular

disease.27 Erection

problems may well be a manifestation of microand/

or macrovascular disease. In the

MMAS sample, “the age-adjusted

probability of complete impotence

was three times greater in subjects

reporting treated diabetes than

in those without diabetes.”6 In an

attempt to clarify

the connection between diabetes

and erection problems and to eliminate the confounding

effects of associated illness and

medications, 40 men with diabetes (but free

of other illness or drugs apart

from antidiabetic medication) were compared to an

equivalent group of age-matched

healthy controls.26 The men with diabetes were

found to have a wide variety of

sex-related difficulties, including:

1. Erectile dsyfunction with

attempts at intercourse, during sleep, and with masturbation

2. Sexual desire disorders

3. Diminished frequency of

intercourse

4. Premature ejaculation

5. Diminished sexual satisfaction

In another study, sexually

functional men with diabetes were shown to have significantly

diminished Nocturnal Penile

Tumescence (NPT) profiles when compared to a similar

control group.28

Cardiovascular Disorders

The association between erectile

difficulties and cardiovascular disorders is well studied.

“Vascular disorders” include two

groups: arterial (i.e., obstruction to the penile

inflow tract) and veno-occlusive

(i.e., the inability to trap blood in the corpus cavernosum).

29 The former has attracted

particular attention.

The presence of four arterial risk

factors (ARF) (diabetes, smoking, hyperlipidemia,

and hypertension) was assessed in

440 “impotent” men.30 The frequency of “organic

Forty men with diabetes with no other

illnesses and taking no drugs other than

antidiabetic medication were compared

to the equivalent group of age-matched

healthy controls.26 The

men with diabetes

were found to have a variety of sexrelated

difficulties, including erectile

function with attempts at intercourse,

during sleep, and with masturbation;

sexual desire; frequency of intercourse;

premature ejaculation; and sexual

satisfaction.

|

impotence” occurred in 49% of men

without any ARF, and 100% when there were

three or four risk factors.

Cigarette Smoking

The link between cigarette

smoking and arterial disease is well established.

Smoking was found to be

significantly more prevalent in men

who were “impotent” compared to

estimates of smoking among men in

the general population.31

In one study, two groups of men with and

without penile arterial disease

were compared, and the former was found

to have smoked more pack-years.32

In the MMAS, “complete impotence”

was higher in current smokers

(versus current nonsmokers) who were also treated

for heart disease, hypertension,

or arthritis, and, as well, in those taking cardiac drugs,

antihypertensives, or

vasodilators.6 In subjects with treated heart disease the

probability

of “complete impotence” in the

MMAS was 56% for current smokers compared to 21%

for current nonsmokers. Likewise,

treated hypertension together with smoking increased

the probability of “complete

impotence” to 20% of those who had both

factors, as compared to 9% among

hypertensive men who did not

smoke. Apart from particular

connections between smoking and other

risk factors, “a general effect

of current cigarette smoking was not

noted.”

Hypertension

The relationship between

“impotence” and “erection dysfunction” and

hypertension was examined in a

review of studies that were conducted in the 1970s

and 1980s33(p.

204). Impotence was found in 7% of men with normal blood pressure.

Impotence was found in 17% to 23%

of untreated men with hypertension and in 25%

to 41% of men who were treated

for hypertension. From these studies, the association

between “impotence” and hypertension

(apart from drugs used in its treatment) is

clearly evident.

Lip ids

In the MMAS, a negative

correlation was found between “impotence” and high density

lipoprotein cholesterol, although

this was not so with total serum cholesterol.

“In the older men (age 56 to 70

years), the age-adjusted probability

of ‘moderate impotence’ increased

from 6.7% to 25% as high

density lipoprotein cholesterol

decreased from 90 to 30 mg./dl.”6

Medications

A variety of drugs used presently

and in the recent past have been shown

to interfere with erectile

function in men (see Appendix III). The increase

in the number of new drugs that

are currently being introduced for various

human ailments and the increased

speed with which they appear on

the market make it likely that

unanticipated side effects (including sexual

side effects) of these agents

will become apparent only after they

have been used for a period of

time. Physicians must therefore be constantly

sensitive to the possibility of

sexual side effects (including effects

Impotence was found in 7% of men with

normal blood pressure. Impotence was

found in 17% to 23% of untreated men

with hypertension and in 25% to 41% of

men treated for hypertension.33

The increase in the number of new

drugs that are currently being introduced

for various human ailments and

the increased speed with which they

appear on the market make it likely

that unanticipated side effects (including

sexual side effects) of these agents will

become apparent only after they have

been used for a period of time. Physicians

must therefore be constantly sensitive

to the possibility of sexual side

effects (including effects on the mechanism

of erection) of newer drugs.

In the MMAS, “complete impotence” was

higher in current smokers (versus current

nonsmokers) who were also treated

for heart disease, hypertension, or

arthritis, and, as well, in those taking

cardiac drugs, antihypertensives, or

vasodilators.6

|

on the mechanism of erection) of

newer drugs. The following comment was made about

hypotensive agents but applies

equally to other drugs as well: “Although . . . certain

agents . . . . are likely to have

sexual side effects [while] other agents . . . are unlikely

to be associated with erectile

dysfunction, it is important to stress that any agent may

cause erectile difficulties in

certain patients . . . there is [also] considerable individual

variation in vulnerability of

erectile function to different drugs. In other words, the existing

literature can only serve as a

general guide to patient management”

(italics added)34 (pp. 111-112).

In the MMAS study, “complete

impotence” was found to be present significantly more

often in men taking the following

medications than in the sample as a whole (10%)6:

• Hypoglycemic agents (26%)

• Antihypertensives (14%)

• Vasodilators (36%)

• Cardiac drugs (28%)

This association was not found

with lipid-lowering drugs.

Two groups of drugs

(antihypertensives and medications used in psychiatry)

have been particularly implicated

in the development of erectile

dysfunction33

(pp. 197-337).

Issues learned from sexual side

effect research on antihypertensive

drugs (that apply to other

substances as well) include the following

items32 (pp.

206-207):

• Possibility of late appearance

(6 months or more)

• Lack of information about their

effects on women

• Importance of assessing sexual

symptoms of the underlying

disease

• Need to include information

from partners

• Usefulness of information about

masturbation

• Need to assess alcohol use and

abuse

Alcohol

“With just a few drinks, most men

experience transient boosts in sex drive and sociability.

With continued drinking, however,

erection and ejaculation abilities systematically

decrease in a dose-related

fashion to a point of total dysfunction.”

32 Although there are acute

and chronic effects of alcohol on sexual

function, comments here focus on

the latter. Studies relating to chronic

alcoholism and epidemiology,

Nocturnal Penile Tumescence (NPT),

hormonal and neurologic effects

have been reviewed.35

An examination of clinical

experience in the care of approximately

17,000 male alcoholics over 36

years revealed that 8% spontaneously

described continued erectile

problems after detoxification.36 Years

later,

despite abstinence, 50% had not

fully recovered their erectile function.

The continuation of sexual desire

in these men indicates that their erectile problems

were unlikely to be simply a

result of insufficient testosterone but rather more fundamental

structural and functional body

changes, including:

• Effect on testosterone

receptors

Issues learned from sexual side effect

research on antihypertensive drugs

include the possibility of their late

appearance (6 months or more), the

lack of information about their effects

on women, the importance of assessing

sexual symptoms of the underlying disease,

the need to include information

from partners, the usefulness of

information

about masturbation, and the

need to assess alcohol use and abuse32

(pp. 206-207).

An examination of clinical experience in

the care of approximately 17,000 male

alcoholics over 36 years revealed that

8% spontaneously described continued

erectile problems after detoxification.36

Years later, and despite abstinence, 50%

had not fully recovered their erectile

function.

|

• Influence of estrogen

• Damage to organs in the body,

including the central nervous system,

testicles, and liver

• Existing diseases caused or

made worse by alcohol abuse such as diabetes,

heart disease, and peripheral

neuropathy

In addition, two controlled

studies on the effects of alcoholism on sexual function

demonstrate that erectile

dysfunction37 and also desire problems38

were more common

in alcoholic men.

In an effort to assess the effect

of alcohol use on NPT, 26 sober, healthy, sexually

functional, and medication-free

chronic alcoholics and controls were studied for two

nights in a laboratory setting.39

The subjects had fewer full penile tumescent episodes

that were also shorter in

duration. The authors speculated on the possible contribution

of central processes to the

effects of alcohol on erections.

The impact of chronic alcoholism

on pituitary-gonadal function appears at both

levels. Apart from liver disease,

chronic alcoholic men show evidence of hypogonadism,

abnormalities in spermatogenesis,

and testicular atrophy.40 Such men

also demonstrate

diminished androgens, elevated

estrogens, and increased prolactin levels.

The neuropsychiatric effects of

chronic alcoholism on sexual function may involve

central and peripheral processes.

Alcohol-induced peripheral neuropathy may result in

both erectile and ejaculatory

disorders. Schiavi outlined many of the psychological

factors that may also be present

such as preexisting personality problems,

mood disorder, and feelings of

inadequacy.35 He concluded that

“the reciprocal interaction

between drug intake and psychological factors

is so closely interwoven that it

is impossible to identify the nature

of this relation.”

Endocrine Abnormalities

“Erectile dysfunction of

exclusively endocrine origin is uncommon. . . In most cases

the primary effect of the

endocrine abnormality is loss of sexual interest.”12 The

authors

of the MMAS study arrived at a

similar conclusion.6” Of the 17 hormones

measured in

the MMAS, “only

dehydroepiandrosterone showed a strong correlation with impotence.”

Specifically, no correlations

were found between “impotence” and the following

hormones:

• Testosterone (total or free)

• Sex hormone binding globulin

(SHBG)

• Estrogens

• Prolactin

• Luteinizing hormone (LH)

• Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH)

When hormonal difficulties occur

in the context of erectile dysfunction, the more

common clinical abnormalities are

those that involve the hypothalamus-pituitarygonadal

axis and include: hypo- and

hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, hyperprolactinemia,

and hypo- and hyperthyroidism.41

(p. 85). The frequency of the association

of endocrine and erectile

problems depends on the age of the sample and the

Erectile dysfunction in all situations,

including the lack of nocturnal erections,

strongly suggests that a general medical

condition or substance use is the cause.5

|

clinical context of the

investigation (e.g., outpatient medical, urology, endocrine, or

sex therapy clinics), as well as

the nature of the sample.

When the particular association

of erection problems and hyperprolactinemia

(HPRL) was reviewed, the

observation was made that this was “often the first, and for

a long time the only symptom of

HPRL, an important point because in many cases the

cause is a pituitary tumor.”12

Buvat and Lemaire reviewed large

published series of endocrine abnormalities in

cases of erectile dysfunction and

when combining their own results with others

found an 8% prevalence for low

testosterone and 0.7% of prolactin levels greater

than 35 ng./ml.42

Aging

See “Sexual-developmenl History:

The Older Years” in Chapter 5.

Laboratory Investigation

When the history and physical

examination (see the “General Considerations” section

above in this chapter) leave

doubt about the origin of a patient’s erectile dysfunction,

the clinician must also consider

the use of laboratory tests.

The availability of orally

administered treatments for erectile dysfunction (for

example, sildenafil—see

“Treatment” below in this chapter) that appear to be easy to

use, often effective, and have

minimal side-effects may well have profound effects on

the process of evaluating

erectile dysfunction. The initial use of these medications by

a patient may, itself, become a

test, and in so doing may replace some other investigatory

procedures. Nothing, however,

should replace a careful clinical assessment and “when

there is suspicion of an organic

factor, one should rely (as well) on a combination of

investigations.”13

Laboratory investigation of

generalized erectile dysfunction chiefly entails examining

three body systems:

• Endocrine

• Vascular

• Neurological

Several diagnostic tests

involving these three systems have been developed. The criteria

used in considering which

diagnostic tests are appropriate for investigating generalized

erectile dysfunction on a primary

care basis are:

1. Usefulness

2. Low cost

3. Noninvasiveness

4. Low complexity

5. Availability

Endocrine Blood Tests

Endocrine and blood tests for

diabetes are probably the only procedures that fulfill the

criteria outlined immediately

above. Despite agreement on the endocrine disorders most

commonly associated with erection

difficulties,“. . . . there is disagreement on the specific

tests to be employed or the interpretation thereof”41 (p.

85). Many

suggest the need to measure

Testosterone (T) and Prolactin (PRL) in all

men with erection difficulty (PRL

can be abnormal when T is not). However,

others promote a more specific

policy. For example, Buvat and

Lemaire suggest that before age

50, T should be determined only in cases

of (accompanying) low sexual

desire and abnormal physical examination

but that after age 50 it

should be measured in all men, and that PRL should

be determined only in cases of

(accompanying) low sexual desire, gynecomastia,

and/or testosterone less than 4

ng/ml.42 These authors also direct clinicians to

repeat first results of abnormal

prolactin and testosterone determinations because of their

finding of normal second results

in 40% of their cases.

Apart from measuring total

testosterone, this hormone also can be determined in the

bioavailable form (BAT) and as

free testosterone (FT). BAT consists of FT and the fraction

that is bound to albumin41

(p. 76).

Conflicting opinions exist over

the need to also immediately test some or all of the

following other factors without

waiting for an abnormal T or PRL result:

• Follicle Stimulating Hormone

(FSH)

• Luteinizing Hormone (LH)

• Sex Hormone Binding Globulin

(SHBG)

• Thyroid function tests

Cost of testing and the nature of

the clinical context are two elements resulting in differences

of opinion. In the literature, it

seems assumed that these other factors would

be measured in the event of an

abnormal T or PRL level.

Tests for Diabetes

Fasting blood sugar (FBS) or

fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and/or glycosylated hemoglobin

(HgA1C)

is widely used as a screening test for diabetes. A positive test indicates

that a confirming diagnostic test

is warranted.43

Vascular Tests

Since the penis is, basically, a

vascular organ, vascular tests are often important elements

in the evaluation of erectile

difficulties, particularly when there is suspicion that

vascular elements may contribute

to the etiology. However, tests of

penile vascular function are

mostly invasive, costly, complex, difficult

to interpret, and have limited

availability. As such they are generally

conducted by urologists and not

recommended in primary care unless a

physician has special training.

Although vascular testing procedures

may not be recommended for use in

primary care, clinicians should be

aware of their potential

diagnostic benefits and limitations to determine

the need for urological

consultation.

Assessment of the penile response

to the intracavernous injection

(ICI) of vasoactive agents has

been found to be particularly useful in

considering vascular function.

While structural problems with cavernosal

arteries may explain a negative

response, anxiety can as well.44 “A

positive erectile response

implies normal veno-occlusive function.

These authors also direct clinicians to

repeat first results of abnormal prolactin

and testosterone determinations because

of their finding of normal second results

in 40% of their cases.

The most worrisome complication of ICI

is that of prolonged erection. After six

hours of continuous erection, there is

insufficient blood supply to the erectile

tissue. The corpora cavernosa must be

drained to decrease the intracavernosal

pressure and an adrenergic agonist

administered, injected intracavernously.

29 In

clinical practice, patients must

be told to contact a physician long

before six hours if their erection

persists.

|

Nonresponders bear a high

probability of a vascular origin with a predominance of

veno-occlusive insufficiency.”29

From a procedural viewpoint, the

most common substances used for intracavernosal

injections are papaverine,

papaverine-phentolamine mixture, or prostaglandin E1

(PGE1).

The most worrisome complication of ICI is that of prolonged erection. A

comparative study of these three

medications demonstrates that PGE1 had the highest

erection rate (75%) and lowest

prolonged erection rate (i.e., requiring “interruption”

[0.1%]).45 After

six hours of continuous erection, there is insufficient blood supply to

the erectile tissue. In this

situation, the corpora cavernosa need to be drained to

decrease the intracavernosal

pressure and an adrenergic agonist (e.g., 10 mg of adrenaline)

injected intracavernosly.29

In clinical practice, patients must be told to contact their

physician

long before six hours if their

erection persists.

Pharmacopenile Duplex

Ultrasonography (PPDU) provides “an estimate of penile

arterial inflow and venous

outflow . . . [and] . . . has become a first-line test to

define vascular [erectile

dysfunction]”29 It allows for accurate location of penile

arteries

and measurement of the diameter

of each artery and provides evidence of the thickness

and pulsatility of arterial

walls.12 In addition to assessment of the state of the

cavernosal

arteries, PPDU can locate

well-defined pathological conditions such as Peyronie’s

disease. The procedure for PPDU

involves the creation of an erection through

ICI (needed because the procedure

is unreliable when a penis is in the flaccid state)

and then simultaneously combining

ultrasound color imaging of the arteries to the

cavernosal bodies of the penis

with an analysis of blood flow patterns.

Nonspecific Tests: Nocturnal Penile Tumescence (NPT)

Any discussion of erectile

dysfunction assessment is incomplete without including

NPT testing, since it is so

widely used and so frequently included in the literature on

this subject. NPT is based on the

discovery that a period of sleep involves different

stages and that one of those

stages (REM) is associated with many body changes,

including the development of

erection in men (three or four times each night and

occupying about 20% of total

sleep time). It was assumed that erections that occur at

night and those which occur

during the day involve the same body mechanisms and

that by comparing sleep and

daytime erections, it would be possible to distinguish the

psychological or organic nature

of the etiology of erection dysfunction. Sleep erections

are considered to be unaffected

by waking psychosocial factors.

When used in-home, NPT testing

fulfills many of the primary care criteria previously

described insofar as it is

inexpensive, not extraordinarily complex to use, noninvasive,

and available. However, when done

in a sleep laboratory, NPT is the opposite

in that it is expensive,

cumbersome, and frequently unavailable in many geographic

areas. The chief doubt about NPT

is its usefulness.

When used in such a way as to

provide clearest interpretation, the test is performed

in a sleep laboratory with

measurement of other sleep parameters such as electroencephalograph

(EEG), respiration, and

electromyograph (EMG), and recordings are

made on at least two nights. The

purpose in monitoring other sleep parameters is the

detection of interference with

sleep or REM such as might happen with illness or

medication, which might result in

mistaken conclusions.

Because of the complexity,

expense, and difficulties with availability associated with

formal testing of NPT in a

hospital setting, three in-home procedures have been developed46

(p. 153):

1. The “stamp” test (a ring of

stamps placed around the base of a man’s penis)

2. Snap Gauge Band (one ring of a

thin plastic material containing three others that

break at three different levels

of tension as a penis enlarges)

3. Portable NPT monitoring

“Stamp” test results are

difficult to interpret because of such problems as falsepositive

findings due to accidental

tearing of the stamps for reasons other than an

erection, false-negative results

due to slippage, and lack of standardization. Snap Gauge

has similarly been found to be of

limited value. Both the stamp test and Snap Guage

provide information about changes

in circumference only, nothing about rigidity or