CHAPTER 10

Ejaculation/Orgasm Disorders

Three

disorders of ejaculation/orgasm are most common in primary care: Premature

Ejaculation [PE], Delayed

Ejaculation/ Orgasm [DE/O], and Retrograde Ejaculation

[RE]. Three others are found

infrequently: Anejaculation, Painful Ejaculation, and

Anorgasmic Ejaculation. The six

conditions are discussed in order of frequency.

Premature Ejaculation

Time and time again premature

ejaculators of many years’ standing not only lose confidence in their

own sexual performance but also,

unable to respond positively while questioning their own masculinity,

terminate their sexual

functioning with secondary impotence. This stage of functional involution is,

of

course, the crowning blow to

husband and wife as individuals and usually to the marital relationship.

Masters &

Johnson, 19701

The Problem

A couple in their late 20s and married for

three years was concerned about the

man’s ejaculation. For religious reasons,

they had not attempted intercourse before

marriage. Since they were married, he

regularly ejaculated before attempts at vaginal

entry. As a result, their union had not

been “consummated.” Her sexual desire

diminished considerably over the three

years of their marriage. Apart from embarrassment

and diminished sexual pleasure that they

both experienced, they wanted

to have children and for her to become

pregnant in the “natural way.” Ejaculating

quickly was not a new problem for him.

Since the first time he attempted intercourse

at the age of 14, he was unable to

accomplish vaginal entry except on one

occasion, and, then, he ejaculated in a

matter of seconds. Since the “squeeze technique”

described by Masters & Johnson1

was tried and found not helpful, the couple

felt desperate and anticipated separation

and divorce if another way to help them

could not be found.

A couple in their mid-50s and married for

25 years was seen because of erectile and

ejaculation problems. Sexual difficulties

began about five years before and were

gradually becoming worse. The husband was

aware of the association between

sexual dysfunctions and diabetes (a disease

with which he lived in the previous 20

years) but until recently had not

volunteered information to his physician about his

sexual difficulties. He believed that the

onset of his (generalized) erectile problems

preceded his ejaculation difficulty by

about one year. He described ejaculating rapidly

after a frantic process of gaining vaginal

entry and before any softening of his

erection made continued containment

impossible.

Terminology

Patients often use the word

“come” to describe an ejaculation/orgasm and “Premature

Ejaculation” when this process

happens too quickly. When the term, Premature Ejaculation

(PE), is used by health

professionals, some consider it to be pejorative and value

laden. Preferring a more

descriptive term, McCarthy has suggested Early Ejaculation as

an alternative2

(p. 144). Others have also used the term, Rapid Ejaculation.3,4

These

terms indicate that speed of

ejaculation is on a continuum from slow to fast rather

than a normal/abnormal dichotomy.

For reasons of consistency with DSM-IV5 and

DSM-IV-PC6 nomenclature,

as well as the inclusion of the concept of control in the

definition (see immediately

below), the term, Premature Ejaculation, will be used in this

chapter.

Definition

Definition problems abound in

attempts to clarify PE. Does one use a time element?

(Critics say that no one carries

a stopwatch to bed.) Or is it better to specify the number

of movements or thrusts? (One

might legitimately ask: just what is the “correct”

number?) Should one follow the

Masters and Johnson suggestion that the woman be

“satisfied” 50% of the time when

intercourse occurs?1 (p. 92) (On the

presumption that

“satisfaction” means “orgasm,” of

what relevance is the Masters and Johnson definition

to a man who is having

intercourse with a woman who comes to orgasm only with

direct clitoral stimulation and

not with intercourse?)

Usually no one debates the issue

of the definition of prematurity when a heterosexual

man ejaculates before, during, or

immediately after vaginal entry. Definition

problems arise with lengthening

of the amount of time after penetration. It is

conceivable that two syndromes

exist: (1) ejaculation before, during, or immediately

after vaginal entry and (2)

ejaculation after vaginal entry but with little or

no control over the timing. It

may be that the former has “premature ejaculation”

and the latter is simply quite

fast and would be reasonably described as having

“rapid ejaculation.”

Grenier and Byers suggest a different

way of considering the definition of PE: there

should be two criteria for the

diagnosis. One is based on the extent of voluntary control

experienced by the man and the

other is based on “latency,” or the amount of time

from vaginal entry to ejaculation.3

Does PE apply to men who are

sexually active with other men? The literature is

unclear on this subject. Masters

and Johnson found that PE “rarely represents a serious

problem to interacting male

homosexuals . . . [since] . . . neither man is dependent

upon the other’s ejaculatory

control to achieve sexual satisfaction”7 (p.

239). However,

another study declared that 19%

of a convenience sample of 197 gay men reported

“ejaculating too soon/too

quickly.”8

If the definition of PE includes

only the speed of ejaculation, the definition

doubtless applies to men sexually

active with other men. However, if the definition

also includes control, the answer

is not so clear. It might depend on the kind of

sexual practices between the two

men. For example, some men might ejaculate rapidly

and out of control during anal

intercourse but rapidly and in control with

mutual masturbation.

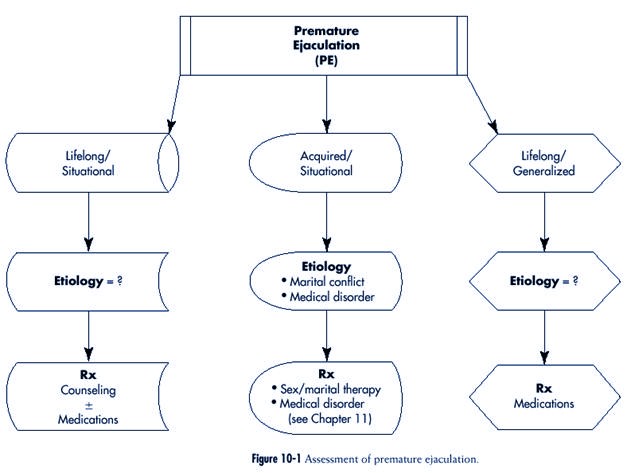

Classification

DSM-IV-PC summarizes the criteria

for the diagnosis of PE as follows: “Persistent or

recurrent ejaculation with

minimal stimulation before, on, or shortly after penetration

and before the person wishes it,

causing marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.”6

(This statement introduces a

subjective element by using the phrase “wishes it”). The

clinician is further instructed

to “ . . . take into account factors that affect the duration

of the sexual excitement phase,

such as age, novelty of the sexual partner or situation,

and frequency of sexual

activity.” As with other sexual dysfunctions, clinicians are also

asked to specify if the problem

is lifelong or acquired, or situational or generalized.

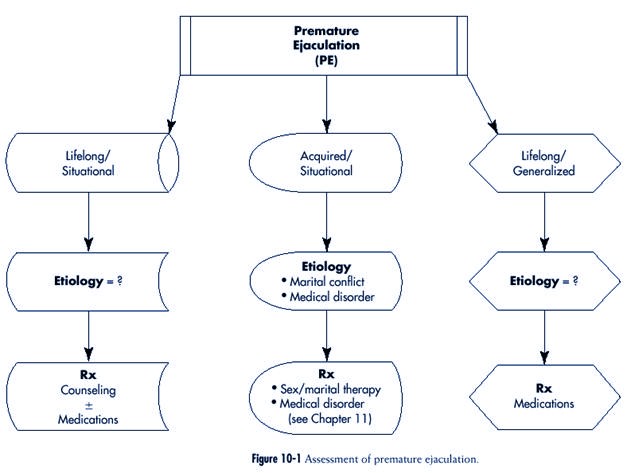

The assessment of premature

ejaculation is outlined in Figure 10-1

Description

The majority of men who ask for

assistance describe a lifelong pattern of ejaculating

quickly and without any control

in attempts at intercourse. This process usually contrasts

with ejaculation with

masturbation, the timing of which is described as entirely

in their control.

History reveals increasing

concern about ejaculation in intercourse after an initial

period in which the man seemed

unaware of possible dissatisfaction of previous sexual

partners (“no one ever said

anything”). His sexual activities tend to focus on intercourse.

On a time scale, the man often

ejaculates within seconds after vaginal entry.

While ejaculation is pleasurable,

the total sexual experience is anything but, since it is

filled with worry and trepidation

about ‘the same thing taking place that occurred the

last time.’ Various attempts at

controlling ejaculation (including distracting oneself by

nonsexual thoughts or

masturbating before a sexual encounter) have been tried and

found wanting. The patient is

apologetic to his partner and privately self-deprecatory.

The current partner is often

angry because her sexual arousal is repeatedly interrupted.

Her interest in sexual activities

may decline. Sometimes a woman in this situation

believes that the man

deliberately chooses not to control the timing of his ejaculation.

Resulting intra- and

interpersonal tensions can be substantial.

Some men describe difficulties

with the timing of ejaculation of relatively recent

onset and after a lengthy period

in which this was not considered to be a problem by

him or his partner(s). The

distinction between this acquired form and its lifelong counterpart

is important from etiological and

therapeutic viewpoints.

Epidemiology

Some information about “normal”

latency was provided by Kinsey and his colleagues

in their survey of men in the

general population9 (pp. 579-581). While they

did not

seem to consider PE to be a

disorder, curiosity about speed of ejaculation

(rather than definition of the

problem) resulted in them asking

about ejaculation latency (that

is, the estimated average time for ejaculation

to occur after vaginal entry).

The time was two minutes for about

three fourths of the men studied.

Laumann and his colleagues asked

those who were surveyed: “during

the last 12 months has there ever

been a period of several months

or more when you came to a climax

too quickly?”10 pp.368-375)

Twenty-nine percent of the men

answered “yes”—the most common

sexual complaint, by far, of the

men surveyed. Positive answers were

greatest in men who were under

the age of 40 and over the age of 54, married and

divorced (compared to those who had

never married), less educated (i.e., received less

than high school education),

black, in poor health, and unhappy.

PE has varied from 15% to 46% of

presenting complaints at sexual problem clinics

in a review of studies completed

between 1970 and 1988.11 Furthermore,

for unknown

reasons, PE may be decreasing

over time as the principal sexual concern of men who

appear at the clinics.

Question: “During the last 12 months

has there ever been a period of several

months or more when you came to a

climax too quickly?” Twenty-nine percent

of the men surveyed answered,

“Yes.” (This is, by far, the most common

sexual complaint of the men surveyed.)

|

The acquired form of PE

(sometimes referred to as “secondary”) is characterized by:

(1) an older man, (2) a briefer

interval of time existing between beginning of the difficulty

and seeking professional

assistance, and (3) erectile difficulties preceding the

onset.12

Etiology

The variety of psychologically

and biologically based etiological hypotheses for PE

have been thoroughly reviewed3

and include the following:

1. Psychodynamic theories

(excessive narcissism or a virulent dislike of women)

2. Early experience (conditioning

based on haste and nervousness)

3. Anxiety (causing activation of

the sympathetic nervous system or distraction

from worry resulting in lack of

awareness of sensations premonitory to ejaculation)

4. Low frequency of sexual

activity

5. Not using techniques that

other men have learned to control the timing of ejaculation

6. Not considering rapidity of

ejaculation to be a disorder, since it is a superior trait

from an evolutionary viewpoint

7. Easier arousal

8. Greater sensitivity to penile

stimulation

9. Malfunctioning of the normal

ejaculatory reflex3

Theories about PE represent

etiological speculations concerning men

who are otherwise healthy.

However, PE has also been reported in

association with trauma to the

sympathetic nervous system during surgery

for aortic aneurysm, pelvic

fracture, prostatitis, urethritis4 and

neurological diseases such as

multiple sclerosis2 (p. 148).

While the presence of anxiety

often seems to be associated with PE,

the direction of the relationship

(cause or effect) is unclear. What is

striking, however, is the fact

that many men (perhaps most) who ejaculate unpredictably

with a partner are able to

control the timing of their ejaculation when masturbating.

(A few men who appear to be

otherwise healthy ejaculate spontaneously and

without control in the presence

of any kind of sexual stimulation.)

Assuming a relationship between

anxiety and ejaculatory control, anxiety

is helpful as an explanation for

the occurrence of PE only in relation

to intercourse (since men are

considerably less anxious when masturbating13).

One of the more compelling

hypotheses for PE is that it “may be,

at least in part, the result of a

physiologically determined hypersensitivity

to sexual stimulation,” that is,

PE may be a reflection of a

lower ejaculatory threshold. In a

study that adds support to this

idea, speed of ejaculation was compared

in premature and nonpremature

ejaculating men when

masturbating. Assessment of latency to ejaculation

showed that when at home the men

with PE ejaculated in about half the time as

their counterparts (three minutes

versus six minutes).11 The authors of this study

suggest a diathesis-stress model

in which “some individuals with a particularly strong

Many men (perhaps most) who ejaculate

unpredictably with a partner are

able to control the timing of their

ejaculation

when masturbating.

Speed of ejaculation was compared in

premature and nonpremature ejaculating

men when masturbating. Assessment

of latency to ejaculation showed that

when at home the men with PE ejaculated

in about half the time as their

conterparts (three minutes versus six

minutes).

|

somatic vulnerability may require

little, if any, anxiety in order to manifest their low

orgastic threshold.”

Investigation into the etiology

of the acquired form of PE suggests separation into

two groups: (1) one in which the

patients had a “demonstrable organic cause” (e.g.,

erectile dysfunction as a result

of diabetes) and (2) one in which the men were involved

in disturbed relationships.12

Investigation

History

The history is the key to the

diagnosis of PE in a man who is otherwise healthy. While

history can be obtained from the

man alone, the effect of this syndrome on both sexual

partners is best gauged by

talking directly with each. Issues to inquire about and suggested

descriptive questions (asked of

heterosexual men, although easily adapted to

gay men as well) include:

1. Duration of ejaculatory

difficulty (see Chapter 4, “lifelong versus acquired”)

Suggested Question: Has

ejaculating quickly always been a problem

for you or was there a period of

time when this did not

occur?”

2. Subjective feeling before

ejaculation (see Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “If you

compare your ejaculation when having

intercourse to masturbating, how

much warning do you

have that ejaculation is about to

occur in each situation?”

3. Timing of ejaculation (see

Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “Do you

ejaculate before, during, or after

vaginal entry?”

4. Speed of ejaculation (see

Chapter 4, “description”)

Question if Answer is “After”: “On

the basis of time, how long does it

take you to ejaculate after

entry?”

Additional Question: “On the

basis of numbers of movements or

thrusts, how many occur before

you ejaculate?”

5. Methods used to control

ejaculation (see Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “Have you

tried to control the timing of

your ejaculation?”

If the Answer is “Yes,” Follow-up

Suggested Question: “What methods have

you used to do this?”

Additional Question: “For

Example, Many Men Stop Moving (or use

condoms, anesthetic creams or

oils, or think of something

nonsexual) in an Attempt to

Prevent Themselves From Getting

Close. Is That Something You’ve

Tried to Do?”

6. Subjective feeling of orgasm

(see Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “Although

orgasm is difficult to describe,

can you explain what it feels

like when you ejaculate?”

Additional Possible Question: “Is

it a pleasant or unpleasant experience

for you?”

7. Description of emission (see

Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “Men

usually experience repeated or rhythmic

contractions when they ejaculate

so that the semen comes

out in spurts. Do you notice

these contractions when you

ejaculate?”

Additional Suggested Question: “When

ejaculation occurs, does the

semen come out in spurts or does

it dribble out?”

(Comment: There is less force to

ejaculation when there is some obstruction [e.g.,

prostatic hypertrophy or urethral

stricture] neurological disorder, and in the aging

process14 [pp.

257-259].)

8. Psychological accompaniment

(see Chapter 4, “patient and partner’s reaction to

problem”)

Suggested Question: “When you

have trouble with ejaculation,

what’s going through your mind?”

Additional Question: “What

does your wife (partner) think?”

Physical and laboratory examinations

In otherwise healthy men, these

investigations add little useful information.

Treatment

Given the substantial frequency

of lifelong Premature Ejaculation in

the community, the focus on

history-taking as the principal diagnostic

technique, the etiological

concentration on the present rather than the

past, and the usefulness of some

brief approaches, treatment of this

disorder is well within the

purview of primary care.

Masters and Johnson described a

talk-oriented treatment method for PE that provides

an “overall failure rate” of 2.7%1

(pp. 92-115 and 367). Perhaps as a result of the

reported benefits, little else

was suggested therapeutically for some time after. Others

also reported positive effects

after treatment but when long-term follow-up studies

Given the prevalence of lifelong Premature

Ejaculation, the focus on historytaking

as the principal diagnostic technique,

the etiological concentration on

the present rather than the past, and

the usefulness of some brief approaches,

treatment of this disorder is well within

the purview of primary care.

|

were done considerably less

robust results were found. A three-year follow-up study

(for example) reported dramatic

changes at the end of treatment for PE in the duration

of intercourse. However,

pretreatment levels returned after three years.15 (Interestingly,

significant improvements in the

duration of foreplay reported at the end of treatment

were found in this study to have

persisted at follow-up.)

Counseling and medications are

presently the mainstays of treatment for lifelong

PE. Obviously, drug prescription

is available only to physicians. However, cooperative

relationships between all

professionals in the health care system increasingly reflect

changes toward improvement in the

quality of patient care.

Pharmacotherapy

Evidence for the utility of drug treatment

of PE is increasing. In case reports and single

blind studies, psychotropic drugs

are noted to interfere with ejaculation as a side

effect.16 Some

investigators reason that this observation could be turned to advantage,

suggesting that a side effect is

not necessarily an adverse effect. The antidepressants

paroxetine,17

sertraline,18 and

clomipramine4 have undergone double-blind testing for

their usefulness in the treatment

of PE (often in smaller doses than that used in the

treatment of depression).

(Paroxetine [Paxil] and sertraline [Zoloft] are selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], and

clomipramine [Anafranil] is a chemical hybrid of

a tricyclic and SSRI).

Waldinger and his colleagues

conducted a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled

study of paroxetine (40 mg/day

for five of the six weeks of the study [higher

than what is usually prescribed

in treating depression]) in the treatment of PE in 17

men.17 Patients

and partners were questioned separately. The improvement was

described as dramatic and began

in the first days of treatment (suggesting that the

effect was not a result of

diminished psychopathology). No anticholinergic side effects

(a possible problem with

clomipramine, depending on the dose) or effect on erection

function was reported.

Mendels and his colleagues

randomly assigned 52 heterosexual males to an eight

week study of either sertraline

or a placebo administered in a double-blind fashion.18

The drug was given daily and the

dose varied from 50 to 200 mg, depending on the

beneficial response and adverse

experiences of the patient. Sertraline was judged to be

significantly better than placebo

in (1) prolongation of time to ejaculation and (2)

number of successful attempts at

intercourse.

Althof and his colleagues

completed a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover

trial of clomipramine in a group

of 15 otherwise healthy men with lifelong PE who

were also married or cohabiting

with a woman for at least six months.4 Partners

participated

in the study. Results of the

study are as follows:

1. Mean ejaculatory latency

increased almost threefold at a dose of 25 mg/day and

over five-fold at the other

studied dose of 50 mg/day

2. Both partners reported

statistically significant greater levels of sexual satisfaction

3. Some of the women who reported

never previously experiencing orgasm with

intercourse became coitally

orgasmic

4. Over half of the 10 women who

previously reported orgasm during intercourse

indicated that it now happened

more frequently

5. The men reported greater

emotional and relationship satisfaction

However, when the drug was

discontinued, sexual function returned to the level that

existed before the study.

The use of clomipramine on an “as

needed” basis was examined19 in

another study.

Using a double-blind,

placebo-controlled, crossover design, eight men with PE, six

men with PE and erectile

dysfunction, and eight control men were studied. Partners

did not participate in the study.

Subjects took 26 mg of clomipramine or placebo 12

to 24 hours before anticipated

sexual activity. In contrast to the marked beneficial

effect in the men with “primary”

(i.e., lifelong) PE, the authors report that the drug was

not useful in men who had PE and

erectile dysfunction. This result affirms the importance

of subclassification.

A 28-year-old man and his 32-year-old wife

were seen because of his difficulty with

regular ejaculation before vaginal entry.

This pattern of ejaculation had existed

since the beginning of his attempts at

intercourse as a teenager. His wife was

becoming sexually disinterested and

questioned her commitment to the relationship,

particularly because “the biological clock

was ticking” and she wanted to

begin a family. The couple had undergone a

Masters and Johnson-type of treatment

program about one year earlier and found

that the initial gains were shortlived.

1 A one-visit assessment

was conducted with them together, and clomipramine

was prescribed. The couple was seen again

two weeks later, when substantial

improvement was reported in the following:

• His ejaculation latency

• Their sexual relationship

• Other aspects of their life as a couple

Much to the wife’s pleasure, she became

pregnant within two months of the first

visit. The man was seen for a third time

alone because the wife was unable to

accompany him for the visit. He reported

continued improvement in sexual and

nonsexual areas of their life. Telephone

contact was periodically maintained for the

purpose of medication refills.

In a review of pharmacologic

studies into the treatment of PE, Althof asks the following

serious questions.4

1. Should drugs be the first line

of treatment?

2. How should drugs be used?

(daily? the day of intercourse? a duration of weeks?

months? lifetime?)

3. What are the indications and

contraindications? (Used only in the lifelong form?

The acquired form? Prescribed

only for men who do not ejaculate before, during,

or immediately after entry but

want to “last longer?”)

4. What should be the

relationship between drug treatment and psychotherapy?

Althof concludes that all of

these questions require empirical research and are therefore

difficult to answer at the

present time. Some of these questions are considered

below, and the information given

is based more on clinical judgment and experience

than research data.

Should drugs be the first line of

treatment? Drugs may well be used immediately, as follows:

• A man who persistently

ejaculates in an uncontrolled manner with any

form of sexual stimulation and

particularly before vaginal entry

• A couple when talk-oriented

treatment methods are not helpful

• Many single men without

partners

• When talking to a couple is

unproductive even if a couple relationship

exists (e.g., in the case of a

couple raised in a culture where gender roles

dictate that the woman is subservient

to the man and both subscribe to

this philosophy—a situation that

is functionally the same as talking

with the man by himself)

How should drugs be used? Daily

and ad hoc (e.g., clomipramine four hours before intercourse

is expected to occur) administration

methods have been found helpful.

What are the contraindications? There

are two reasons why drug treatment should not

be used in men who have the

acquired form of PE based on relationship discord. First,

PE in this situation is clearly

symptomatic and it makes little sense to treat the symptom

and not the “disease” (i.e., the

relationship discord). Second, the

problem of PE may well be

reversed with attention given to the disrupted

relationship. Furthermore, in

acquired PE associated with erectile

problems, clomipramine treatment

has been shown to be ineffective.

17 On the subject of

contraindications, Althof also counseled that

considerable caution be exercised

in response to requests from men

who want “boundless intercourse

or designer orgasmic capabilities.”4

What should be the relationship

between drug therapy and psychotherapy?

Althof states that there should

not be an either/or attitude to the use of

these treatment methods and that

both may be desirable or necessary.4

“The two treatment approaches are

not to be compared solely in terms

of economics or ejaculatory

latency. Psychotherapy educates, clarifies,

and often addresses other issues

not perceived when the diagnosis was

originally made.” Indeed, if the

physician’s approach to medications is such that psychotherapy

is not used in

conjunction, then, by experience so far, the man is implicitly

being told that he must take this

medication for, perhaps, a lifetime. The implications

of such a treatment decision are

substantial, especially given that many of the men

presenting with the lifelong and

situational form of PE are young and in the early

stages of their sexual

experience.

Counseling

The talking part of the treatment

of someone with PE includes at least four components:

If the physician’s approach to medications

is such that psychotherapy is not

used in conjunction, the man patient is

implicitly being told that he must take

this medication for (perhaps) a lifetime.

The implications of such a treatment

decision are substantial, especially since

many men presenting with the lifelong

and situational form of PE are young

and in the early stages of their sexual

experience.

|

• Information

• Specific techniques

• Adaptation

• Attention to psychological

issues

Some are easily incorporated into

primary care practice.

INFORMATION

PE-related self-help books seem

to be particularly useful in providing two elements

of counseling20-22:

• Information (in this instance

about men and sexual issues)

• Specific advice (in this

example about controlling ejaculation)

The extent to which these two

elements are therapeutically helpful is unclear, since

men who benefit greatly from such

books would not be likely to seek assistance from

health professionals. Judging by

the reaction of patients to whom such books are suggested,

many find the content to be at

least informative and reassuring and some follow

the specific treatment methods

suggested. Apart from specific issues around ejaculation

control, Zilbergeld, in

particular, interests male readers when discussing the

powerful and influential sexual

“myths” that so often determine how men think and

behave sexually—in their own eyes

and in those of their sexual partners.20,22 This

is

“sex education” as it should be,

that is, the description of body parts and their function

and the discussion of sex-related

aspects of human relationships. Kaplan’s book includes

information about PE and specific

techniques for ejaculatory control (see immediately

below).21

SPECIFIC TECHNIQUES

A second element in counseling,

more applicable to couples, is directed at specific

techniques to control the speed

of ejaculation. Two approaches were described in the

past: “stop-start”23

and the “squeeze technique”1 (pp.

102-104). The stop-start technique

is more popular among sex

therapists because it is easier for health professionals

to explain and for patients to

use. The stop-start approach involves an exercise in

“communication” and comprises at

least four steps:

1. Both partners initially agree

not to attempt intercourse on at least several occasions

(this is essential)

2. The woman stimulates the man’s

erect penis until he is close to ejaculation at

which point he signals her to

stop

3. This happens three or four

times on any one sexual occasion before he eventually

ejaculates

4. The couple then integrates

this into intercourse experiences with frequent

“pauses”

ADAPTATION

An additional facet of

counseling, also more directed to couples, is incorporated

into the concept of adaptation.

Even if little change develops in the timing or speed of

ejaculation as a result of

talking forms of treatment, a considerable shift may occur in

the sexual experiences of the

couple such that the timing of the man’s ejaculation

becomes a lesser or even

nonissue. For example, if the usual “order” of sexual events is

such that the man ejaculates

before his partner is stimulated, this process can be altered

so that attention is given to the

woman’s satisfaction and (possibly) orgasm, before or

after vaginal entry occurs. The

notion of adaptation is consistent with some results

found at follow-up, namely that

treatment of PE may change aspects of foreplay rather

than ejaculatory control.12

PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUES

Ignoring concurrent psychological

issues in the counseling process decreases the

potential for a good outcome.

A couple in their late 30s, married for 15

years, was referred because the man

regularly ejaculated immediately after

vaginal entry, a pattern that existed throughout

all of his life. In the process of

initially talking with both (together and separately)

it became clear that she was angry and “at

the end of (her) rope.” She was

seriously considering separation for sexual

and nonsexual reasons. Sexually, her

level of interest was similar to her

husband’s (i.e., substantial) but her sexual arousal

was interrupted continually by his

ejaculation. She was orgasmic with direct clitoral

stimulation before intercourse but this was

irregular and unpredictable. Her

animosity toward her husband about

nonsexual concerns related to his inclination

to continually avoid talking about

contentious issues (including their sexual troubles).

It was evident that simply delaying his

ejaculation by using pharmacotherapy

would not circumvent the discord between

the two. Thus deliberate decision was

made to treat this couple using traditional

counseling methods.

Psychological issues may be

particularly important in the solo male. A man might ask

for solo treatment for several

reasons:

1. He may not have a partner

2. Confidentiality and trust

issues may prevent the involvement of a new partner

3. A partner may be unwilling or

unable to participate in the process (this is less

frequent than many men report)

In such circumstances, it is

usually best to explain that although much can be accomplished

diagnostically in seeing him

alone, the absence of a sexual partner is often

therapeutically limiting. Some

aspects of the multifaceted treatment approach described

above can be applied to the solo

male, including the provision of information and

learning specific techniques such

as stop-start while masturbating.

When the limitations of solo

(versus couple) treatment are discussed, clinicians frequently

meet with a “catch-22” response

in which the man says that the very existence

of this problem prevents

establishment of a relationship. He is, in effect, saying that

speed of ejaculation is a

determining force in relationships between men and women—

a suggestion that (to say the

least) not everyone supports. The fact that a partner is not

present to possibly refute this

argument puts the health professional in the difficult

position of presenting a

different point of view to the patient and potentially disrupting

the professional relationship in

the process. Psychotherapy might be helpful to the

extent that the man is prepared

to examine all aspects of a failed relationship, sexual

and otherwise.

Indications for Referral for Consultation or Continuing

Care by a Specialist

1. Consultation with a physician

is required when pharmacotherapy is considered

and the health professional is

trained in a different discipline.

2. In the acquired form of PE

associated with relationship discord, the ejaculation

issue is likely symptomatic and

treatment would involve relationship therapy—

a process that is best undertaken

on a continuing care basis by those in the

health care system with clinical

experience in this area, that is, mental health

professionals.

3. In the acquired form of PE

associated with an erectile disorder, managing both

problems may be complex. Therefore

referral to a sex-specialist for continuing

care may be necessary.

4. Care of the solo man, beyond

the use of drugs, often presents a dilemma.

Men who are unwilling to use

pharmacotherapy or who continue to have

inter- or intrapersonal

difficulty despite slower ejaculation are best seen for

continuing care by a mental

health professional who is comfortable with sexual

issues.

5. Unsuccessful treatment at the

primary care level should result in referral to a

sex-specialist, at least for consultation,

and possibly for continuing care.

Summary

Premature Ejaculation (PE) in

heterosexual men is difficult to define precisely except

in situations where ejaculation

occurs persistently before, during, or immediately

after vaginal entry. Control over

the process of ejaculation appears to be a significant

element in the definition, as

well as the duration of time between vaginal entry

and ejaculation. Most men with

this disorder describe a lifelong pattern. “Coming

to a climax too quickly” was the most

common sexual complaint registered by

men in a substantial survey of

sexual behavior. An unreplicated study suggests an

appealing hypothesis for the

etiology of the lifelong form of PE, namely, that it is

partly related to a

“physiologically determined hypersensitivity to sexual stimulation.”

The acquired form seems to be the

result of relationship discord or medical

illness. The focus of

investigation into the lifelong form of PE is particularly on

history-taking (rather than

physical examination or laboratory studies). Counseling

and medications are the mainstays

of treatment of this disorder. The latter has

demonstrated great value,

although many details concerning drug treatment have

yet to be elaborated.

Long term follow-up studies of

counseling alone show modest results. The potential

value of combining the two

treatment forms has not been investigated. Intuitively,

medications may be considered a

short-term intervention, and psychotherapy may be

included toward the long-term

goal of permanent change. Referral for consultation

with a physician is required when

drug therapy is undertaken by a health professional

from another discipline. Referral

for continuing care is particularly reasonable in the

acquired form of PE and when

slowing of ejaculation in a man seen alone has resulted

in limited success in allowing

him to develop intimate relationships.

Delayed Ejaculation/Orgasm

Terminology

This syndrome has been variously

called:

• Ejaculatory Incompetence1

• Retarded Ejaculation24

• Male Orgasm Disorder5,6

An evident problem with the terms

is the confusion about whether this is a disorder of

ejaculation, of orgasm, or both.

These two phenomena are separate from a neurophysiological

viewpoint although usually

tightly interwoven. The separateness is evident

in the normal development of

preadolescent boys who are able to come to orgasm

but who cannot ejaculate because

the mechanism is not fully developed. The term,

Delayed Ejaculation/Orgasm (DE/O),

is preferred because it is entirely descriptive and

DE/O refers to a delay in both

ejaculation and orgasm.

Definition

Defining DE/O presents problems

similar to PE, namely, the question of how much

time constitutes a delay? In one

form, the definition of time is not a problem, since

the man can ejaculate without

difficulty when alone (without any delay), but usually

not at all when with a partner.

When ejaculation is truly delayed, it is slow in all

situations—regardless of the

sexual activity and the nature of the partnership. In fact,

ejaculation/orgasm may be so

delayed that the person stops trying. In either case

(delayed or absent) the

definition is usually provided by the patient as he, for example,

compares his present experience

to that of the past or receives complaints from

a sexual partner who may become

vaginally uncomfortable because of a lengthy

period of intercourse.

Classification

In DSM-IV-PC, orgasm difficulties

for men and women are classified similarly6 (p.

117). “Male Orgasmic Disorder” is

defined as: persistent or recurrent delay in, or

absence of, orgasm after a normal

sexual excitement phase. This can be present in all

situations, or present only in

specific settings, and causes marked distress or interpersonal

difficulty. Additional clinical

information is provided: “In diagnosing Orgasmic

Disorder, the clinician should

also take into account the person’s age and sexual experience.

. . . In the most common form of Male Orgasmic Disorder, a male cannot

reach orgasm during intercourse,

although he can ejaculate with a partner’s manual or

oral stimulation. Some males. . .

. can reach coital orgasm but only after very prolonged

and intense noncoital

stimulation. Some can ejaculate only from masturbation.

When a man has hidden his lack of

coital orgasm from his sexual partner, the

couple may present with

infertility of unknown cause.” Determining the subclassification

as lifelong or acquired,

generalized or situational can be crucial to determining

etiology and treatment.

The assessment of Delayed

Ejaculation/Orgasm is outlined in Figure 10-2.

Description

DE/O presents clinically in one

of two forms:

• Situational

• Generalized

When situational, the problem is

usually lifelong rather than acquired. When generalized,

it is much more likely to be

acquired.

In the situational form, the

history is usually one of ejaculation without difficulty

when alone but inability to

ejaculate with partners generally or during a specific sexual

activity, typically intercourse.

The request for assistance often can be traced to the

partner and characteristically

results from vaginal discomfort, concerns about reproduction,

or both. Sometimes the man

describes a method of masturbation that is difficult

to transfer to sexual activity

with a partner (e.g., rubbing his penis against a firm

surface rather than using his

hand).

Two gay men in their 20s were seen because

one was unable to ejaculate in the

presence of the other while having no such

difficulty when masturbating alone.

Strains in their relationship became

apparent when the sexually functional partner

let it be known that he considered his

partner’s inability to ejaculate to be a form

of rejection. History revealed that the man

with DE/O experienced this pattern of

ejaculation in previous brief sexual

relationships as well as the three he considered

long-term. Treatment using the approach

described by Masters and Johnson was

unsuccessful at reversing the pattern1

(pp. 129-133). One-year follow-up revealed

that the relationship had dissolved.

In the generalized form (lifelong

or acquired), history reveals that the man is experiencing

substantial delay or absence of

ejaculation/orgasm in all circumstances. Typically,

the history is brief and clearly

indicates that this is acquired and dates from the

onset of the use of a particular

medication (see “Etiology” below in this chapter). Occasionally

this may be life long. Cultural

or religious beliefs may also be a critical factor.

On some occasions, the history

reveals a hybrid form, that is, one that has characteristics

of both syndromes. Ejaculation is

possible but only during masturbation.

When ejaculation does occur in

such circumstances, vigorous and lengthy penile

stimulation is usually

required—much more so than can be provided by vaginal

intercourse.

A 35-year-old single man described an inability

to ejaculate with a partner in spite

of intercourse lasting up to one hour.

Women partners initially enjoyed the experience

and would find themselves repeatedly

orgasmic. However, this attitude

was soon replaced by one of impatience as

the pleasure was superseded

by the vaginal discomfort accompanying the

long duration of

intercourse. He described being able to

ejaculate only with masturbation

in a process that required about 15 minutes

and great physical exertion

in which he “worked” so hard he would

sweat. He forcefully rubbed

his penis against a hard surface while

fantasizing about himself dressed

as a woman.

In the Lauman study,10

8% of men

reported being “unable to orgasm.”

(The investigators did not apparently

distinguish between ejaculation/orgasm

that was delayed and that which was

entirely absent.)

|

Epidemiology

In the Laumann study, 8% of men

reported being “unable to orgasm”10(pp.

370-374).

(The investigators did not

apparently distinguish between ejaculation/orgasm that was

delayed and that which was

entirely absent.) The age category in which this syndrome

was reported with greatest

frequency was the 50 to 54 year old group (14%). Inability

to come to orgasm was also

reported more commonly in “Asian/Pacific Islander” men

(19%), as well as those who were

poorly educated (13%—less than high school), and

financially poor (16%). As with

other dysfunctions, the percentages of affected men

increased with diminished health

(18% of those whose health was “fair”) and happiness

(23% of men who were “unhappy

most times”).

“Male Orgasm Disorder” accounted

for 3% to 8% of cases presenting for treatment

in a review of clinical studies.11

Etiology

In the situational and hybrid

forms, it is evident that specific sexual and/or psychosocial

factors are central to

etiological speculations25 (pp.179-185);

1(p. 126). Theories

include:

1. That some men are highly

reactive genitally

2. That some men are fearful of

dangers associated with ejaculation

3. An inhibition reflex

4. Religious orthodoxy

5. Male fear of pregnancy

6. Sexual interest in other men

7. A psychologically traumatic

event

In the acquired and generalized

form, there is often a history of recent

use of a medication that is known

to interfere with ejaculation/orgasm (see Appendix

V) or the presence of a

neurological disorder such as multiple sclerosis.

“All of the drugs approved for

the treatment of depression or the treatment of

obsessive-compulsive disorder in

the United States, with the exception of nefazodone

and bupropion, have been reported

to be associated with ejaculatory or

orgasmic difficulty.”26

Prevalence figures for any one of the drugs varies as a result

of different sources

(manufacturer or published report) or variations in methodology

(spontaneous reports or direct

inquiry). Ejaculatory problems (delay or inhibition)

have been reported in patients

taking the following drugs:

• Imipramine (30%)

• Phenelzine (40%)

• Clomipramine (96%)

• Fluoxetine (24% to 75%)

• Sertraline (16%)

• Paroxetine (13%)

• Venlafaxine (12%)

Some antihypertensive drugs also

interfere with ejaculation/orgasm. One of the problems

in investigating the extent of

this problem is that hypertension can cause sexual

All drugs approved for treatment of

depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder

in the United States with the

exception of nefazodone and bupropion

are reported to be associated wih

ejaculatory

or orgasmic difficulty.26

|

difficulties apart from the drugs

used in its treatment. “Ejaculatory dysfunction” was not

found at all in two studies that

included normotensives, but was associated with 7% to

17% of untreated, and 26% to 30%

of treated patients27 (p. 204). Antihypertensive

drugs that can cause sexual

difficulties were reviewed27: and, in

relation to delayed

ejaculation, specifically included

the following:

• Reserpine (p. 216)

• Methyldopa (p. 219)

• Guanethidine (p. 224)

• Alpha1 blockers

(p. 235)

• Alpha2 agonists

(p. 237)

• Calcium channel blockers (p.

245)

Notably missing from this list

were the following:

• Diuretics (p. 210)

• Beta-blockers (p. 227)

• ACE inhibitors (p. 242)

Investigation

History

1. Duration (see Chapter 4,

“lifelong versus acquired”)

Suggested Question: “Has

ejaculation difficulty been a problem all

your life or is it a problem that

developed recently?”

2. Ejaculation with a partner

(see Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “Do you

ejaculate at all now when you are

with a partner?”

Additional Question if the Answer

is “No”: “Have you ever ejaculated with

a partner?”

Additional Question if the Answer

to Either Previous Question is “Yes”: “What kind

of sexual activity resulted in

your ejaculation (e.g., intercourse

or oral stimulation)?”

3. Ejaculation with masturbation

(see Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “Do you

ejaculate now when you masturbate?”

Additional Question if the Answer

is “No”: “Have you ever ejaculated

when you masturbated?”

4. Feeling prior to

ejaculation/orgasm (see Chapter 4, “description”)

Suggested Question: “Do you

sometimes feel that you are close to

ejaculation/ orgasm but then the

feeling disappears?”

Additional Question: “When

with a partner, Do you ever pretend

that you have come to orgasm?”

Physical and Laboratory Examinations

In an otherwise healthy man, no

particular physical or laboratory examinations are

required.

Treatment

In the care of men with the

situational form of DE/O, reported series are few. Masters

and Johnson described their

treatment format and their five-year follow-up of 17 men

and reported a treatment failure

rate of 17.6%1 (pp. 116-136, p.357). Another threeyear

follow-up study in the United

States described the treatment of five men15 who

reported themselves as:

Three men Improved

One man The same

One man Worse

A one to six year follow-up study

conducted in the United Kingdom

described two cases of

“ejaculatory failure” and reported that in one

there was no change, and in the

other, the problem was resolved

although still experienced.28

No other case studies involving large

numbers of patients have been

published.

On the basis of impression rather

than data, the occasional man with DE/O asks for

care in his teens, and soon after

intercourse experiences have begun. Such men may be

amenable to the reassurance and

provision of information that often comes with history-

taking alone. The health

professional might be justifiably optimistic about the

result in such circumstances.

Unfortunately, in most instances, men with DE/O do not

ask for treatment until years

later when they are pressured into it by a sexual partner.

By that time, many sexual

experiences have taken place (either alone or with partners)

with a particular method of

ejaculation, a pattern that may have become crystallized

and difficult to change.

In the generalized form of DE/O,

and when there is reason to suspect the use of a

medication in the etiology, the

following treatment “strategies” are suggested:

1. Maintain dosage of the

medication and wait for tolerance to develop

2. Reducing the dosage

3. Change the regimen (e.g., the

use of a “drug holiday”)29

4. Change to an alternative

medication (e.g., when the sexual side effects of sertraline

and nefazodone were compared in

the treatment of depression, nefazodone

was said to have no inhibitory

effects on ejaculation)30

5. Administer a second medication

to counter the sexual side-effect of the first (see

immediately below)26

Men with DE/O usually do not ask for

treatment until they are pressured into

it by a sexual partner. By then, many

sexual experiences may have taken

place, resulting in a firmly established

pattern of ejaculation that may be

difficult

to change.

|

Two potential problems exist when

using other medications at the same time: the clinician

must ensure that the second

medication does not counteract the therapeutic impact

of the first, and sexual

spontaneity inevitably diminishes somewhat when planning

precedes the sexual event

(although often an exaggerated patient concern).

Segraves described seven

medications that have been used in an effort to control

the sexual side-effects of

antidepressants (mostly SSRIs): bethanechol, cyproheptadine,

yohimbine, amantadine, bupropion,

dextroamphetamine, and penoline.26 Methylphenidate

has been suggested31

also, as well as intermittent nefazodone32 (Box

10-1 and

Table 10-1).

Since outcome research has not

subclassified patients, one can only provide clinical

impressions about the generalized

and lifelong form of DE/O. Given that biological

factors likely explain the

etiology, helping the patient adapt through the provision of

information seems the optimal

approach.

Box 10-1

Strategies in Treating Delayed Ejaculation/Orgasm due to Antidepressant Drugs

1. Wait for tolerance to develop

2. Decrease dosage

3. Change regimen (e.g., “drug holiday”)

4. Use alternate drugs

5. Use additional drugs (“antidotes”)

|

1

1

Indications for Referral for Consultation or Continuing

Care by a Specialist

1. Situational DE/O: If this

pattern of ejaculation has existed for some years, referral

for sex therapy for the purpose

of continuing care may be most beneficial

2. Acquired and generalized DE/O:

where medications seem etiologically significant

but the symptom has not altered

with the strategies outlined in Box 10-1, it

is reasonable to ask for advice

(consultation) from a physician who has expertise

in the use of the particular

class of drugs.

3. Lifelong and generalized DE/O:

if the provision of information and reassurance

about the likely positive outcome

proves insufficient, referral to a sex therapist

for continuing care is the next

logical step

Summary

Delayed Ejaculation usually

represents a disorder (delay or absence) of both ejaculation

and orgasm, hence the use of the

abbreviation, “DE/O.” The disorder appears in

two forms:

• Situational, in that the man

can come to ejaculation/orgasm without

problem when alone but has great

difficulty when a partner is present

• Generalized in the sense that

the man has difficulty under all circumstances

(with a partner or when alone

with masturbation)

While unusual, the problem of

delayed ejaculation is by no means rare (8% of men in

one community survey indicated

inability “to orgasm”). Etiologies are as follows:

1. The situational form includes

significant psychosocial factors

2. The lifelong and generalized

form includes biological factors that have not yet

been defined

3. The acquired and generalized

form can usually be explained by the use of medications

(especially medications used in

Psychiatry and in the control of hypertension)

or the onset of a neurological

disorder

The effects of treatment in the

situational form seem better when the duration of the

problem is brief. Several

approaches are suggested for the generalized and acquired

form where the etiology is

related to medications. Treatment for the lifelong and generalized

form can generally be undertaken

initially on a primary care level through the

provision of information and

reassurance. Men with the acquired and generalized form

who have never ejaculated in the

waking state require care from a specialist.

Retrograde Ejaculation

Definition

Retrograde ejaculation (RE) “is

the propulsion of seminal fluid from the posterior urethra

into the bladder”.33

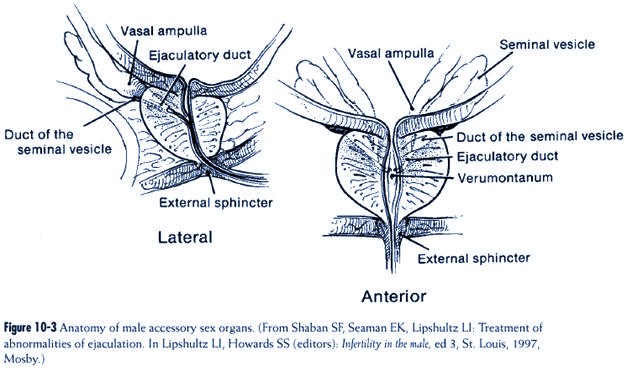

What is usually referred to as “ejaculation” actually comprises

three separate events34

(p. 423):

• First, “emission”

• Second, closure of the “bladder

neck”

• Third, “ejaculation”

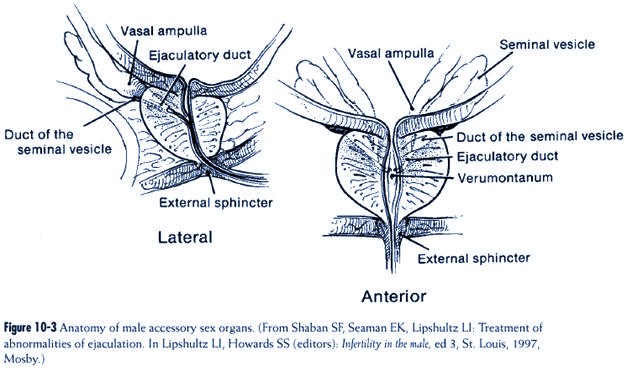

Emission involves the deposition

of seminal fluid from the vas deferens, the seminal

vesicles, and prostate gland into

the posterior urethra. Ejaculation refers to the expulsion

of semen from the penis, which,

in turn, requires simultaneous closure of the

muscular valve at the junction

between the urethra and bladder (the bladder “neck”).

This blockage prevents the semen

from traveling backward into the bladder instead of

going forward out the end of a

man’s penis. The expulsion of semen (true ejaculation)

also involves intermittent

relaxation of the “external sphincter”; there are three to seven

contractions about 0.8 seconds

apart (see Figure 10-3).

The final portion of this process

comprises rhythmic contractions of the bulbospongiosus

and ischiocavernosus muscles,

resulting in forward movement of seminal fluid

through the anterior urethra and

emerging from the penile meatus. Orgasm is considered

a cerebral event that occurs

together with emission or ejaculation and associated

with unknown physiological

mechanisms35 (p. 155).

Emission and bladder neck closure

appear to be predominantly under the control of

the sympathetic portion of the

autonomic nervous system, and the expulsion of semen

is predominately under the

influence of the somatic nervous system35 (pp.

165-166).

“Any interference (anatomical,

traumatic, neurogenic or drug-induced) with (the integrity

of these systems) may result in

abnormal function of the internal sphincter of the

urethra, and favor retrograde

ejaculation (RE) as the path of least resistance”.36

Etiology

One way of considering

etiological factors in RE is to separate them into (1) ones that

disrupt the anatomy of the

sphincter at the bladder neck and (2) ones that interfere

with this sphincter’s function37

(p. 383). The best example of an anatomical disruption

of this sphincter is a

transurethral prostatectomy (TURP). Examples of factors that

interfere with function of this

sphincter include the following:

1. Retroperitoneal lymph node

dissection (RPLND) or total lymphadenectomy in

the treatment of some testicular

cancers

2. Diabetes

3. Abdominopelvic surgery

4. Spinal cord injury

Some medications can induce a

pharmacologic “sympathectomy” resulting in failure of

emission and/or bladder neck

closure (see Appendix V). These drugs34 (p. 427)

include

the following antipsychotics

(e.g., chlorpromazine and Haldol), antidepressants (e.g.,

amitriptyline and SSRIs),

antihypertensives (e.g., guanethidine, diuretics and prazosin),

and others (including alcohol).

Epidemiology

RE seems to be common as a

complication of TURP but the actual frequency is not

entirely clear. In one study of

men before and after surgery, 24% who had no presurgical

difficulty with ejaculation

answered “yes” to the following question after surgery:

“Do you have difficulty with

getting the sperm out?”38 However,

37% of the

men who had no presurgical

difficulty also said that they had no ejaculatory problem

afterward.

Given the frequency with which RE

seems to occur as a result of

TURP, the aging of the population

(assuming TURP continues to be

medically popular as a treatment

of benign prostatic hypertrophy)

might well result in an increase

in the prevalence of RE.

RE seems to be infrequent as a

cause of infertility in men (up to

2%)37 (p.

383).

Investigation

History reveals that the patient

reports not ejaculating while (in the

majority of cases) continuing to

experience orgasm (“dry orgasm”). The

definitive diagnosis is made by

laboratory examination of the man’s

urine immediatly after orgasm,

and finding spermatozoa in the sample.

Treatment

Most men who develop RE as a

consequence of TURP accept this situation and do not

ask for treatment. When care is

required (usually because of infertility), RE is best

managed by physicians. The focus

of infertility treatment is on attempting to induce

antegrade ejaculation by

increasing sympathetic tone at the bladder neck or diminishing

parasympathetic activity.33

Alpha-adrenergic agents are commonly used to enhance

Most men who develop RE as a consequence

of TURP accept this situation and

do not ask for treatment. When care is

required (usually because of infertility),

RE is best managed by physicians. The

focus of infertility treatment is on

attempting to induce antegrade ejaculation

by increasing sympathetic tone at

the bladder neck or diminishing

parasympathetic

activity.33

|

sympathetic tone. In a detailed

study of one patient who stopped ejaculating as a result

of lymphadenectomy, four such

drugs were used39 and all seemed equally efficacious:

1. Dextroamphetamine sulphate, 5

mg four times daily

2. Ephedrine, 25 mg four times

daily

3. Phenylpropanolamine, 75 mg

twice daily

4. Pseudoephedrine, 60 mg four

times daily

The study concluded that

long-term treatment was consistently more effective than a

single dose. Elliott (personal

communication, 1997) found that in patients who have

RE as a result of a spinal injury

the effects of pseudoephedrine, in particular, can diminish

if used continuously for more

than four days, and that it may be more useful to use

it on an “as needed” basis

Anticholinergics have also been used successfully (brompheniramine

8 mg twice daily) and imipramine

(25 to 50 mg daily). Surgery has also been

suggested.33

When antegrade ejaculation can not

be restored the treatment of infertility involves

inseminating the woman with sperm

cells taken from the urine by the process of centrifugation.

In one group of eight patients

with RE, the combination of alkalinization

of the urine, immediate removal of

sperm cells from the urine, and the implementation

of artificial insemination

techniques resulted in a “fecundity rate” of 45%40 (p.

440).

When psychological concerns

exist, they often relate to surprise and apprehension

if, for example, a patient who has

undergone a TURP was not forewarned about not

seeing semen when he ejaculates.

Psychological concerns may also be about other

accompanying factors such as the

possible presence of erectile or orgasmic difficulties

and infertility. These other

issues can have powerful repercussions.

Indications for Referral for Consultation or Continuing

Care by a Specialist

As an isolated issue, RE does not

appear to be a cause of further sexual difficulties. To

the extent that sexual concerns

are related to information, primary care treatment is

usually sufficient. Consultation

with a sexual medicine specialist may be useful in

instances when RE is associated

with other sexual difficulties. When infertility concerns

result from RE (generally younger

men of reproductive age who have experienced

retroperitoneal lymph node

dissection or total lymphadenectomy for the treatment of

testicular cancer), continuing

care should be undertaken by an expert physician.

Summary

Retrograde ejaculation (RE) is

usually reported by a man as an orgasm without the

associated emergence of semen

(“dry orgasm”). Semen travels “backward” into the

bladder and the definitive

diagnosis can be made by the finding of spermatozoa in the

urine. The most common cause of

RE is the TURP procedure for benign prostatic

hypertrophy. For most men,

information is the only treatment needed. When fertility

is a concern, medical treatment

focus is on the attempt to enhance sympathetic tone

at the bladder neck by using

alpha-adrenergic agents or diminishing parasympathetic

activity. Specialist care is

required only in those instances where there are associated

sexual difficulties or concerns

about infertility.

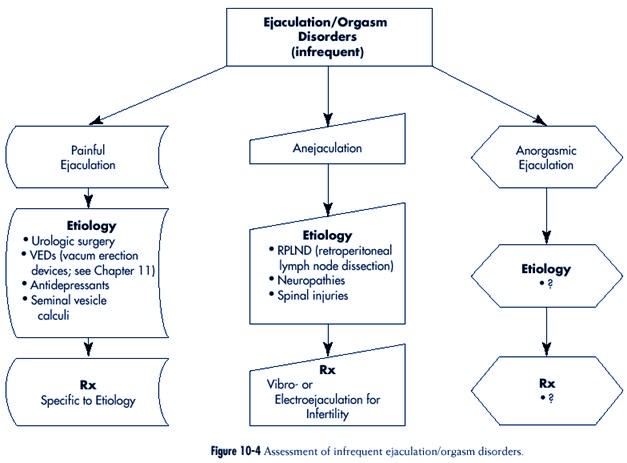

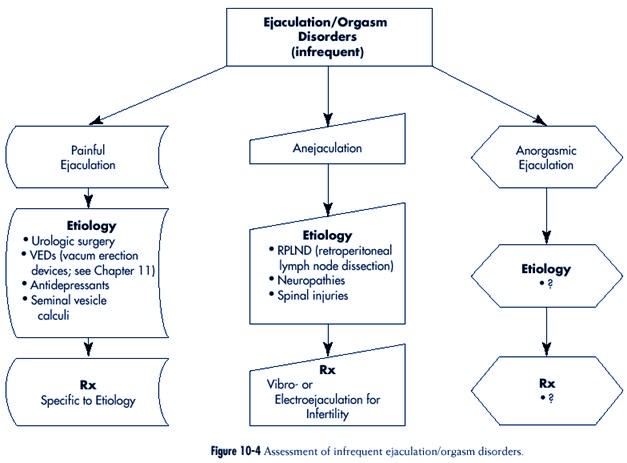

Infrequent Ejaculation/Orgasm Disorders

Infrequent ejaculation/orgasm

disorders include painful ejaculation, anejaculation and

anorgasmic ejaculation. The

assessment of infrequent ejaculation/orgasm disorders is

outlined in Figure 10-4.

Reports of genital pain

associated with ejaculation are uncommon. The following

four causes are known:

1. Some of the tricyclic

antidepressants (amoxapine [related to loxapine], imipramine,

desipramine, clomipramine)41,42

2. Seminal vesicle calculi43

3. Urological surgery

4. Vacuum erection devices (VEDs)

The first two explanations may

not be immediately apparent. When associated with

tricyclic antidepressants,

ejaculatory pain is dose-related so that it diminishes when the

dose is decreased and disappears

when the medication is discontinued.42

The absence of ejaculation, or

anejaculation (antegrade or retrograde), occurs as a

result of peripheral sympathetic

neuropathy44 (pp. 404-6). It occurs in men with spinal

cord injury, men who had

retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) for testicular

cancer, and in neuropathies such

as those seen in multiple sclerosis and diabetes.

Diagnosis is based on the absence

of seminal fluid in postejaculatory urine to eliminate

the possibility of RE.

Emission/ejaculation and subsequent pregnancy can result from

the use of specialized procedures

such as vibratory stimulation or electroejaculation.45

Ejaculation without orgasm is

quite unusual judging from the literature and clinical

experience. The etiology is

unknown.

A 47-year-old man was seen with the

complaint of ejaculating without the sensation

of orgasm. He vividly recalled the powerful

feeling of orgasm in the past and

hoped that it would return. The sensation

of orgasm tapered during the past three

years so that it was virtually absent at

the present time—regardless if he ejaculated

with masturbation or with a partner. He had

previously been married for 12 years

and had experienced premature ejaculation

throughout all of the marriage. In four

of the seven years after his divorce, his

sexual experiences with other women were

described with relish, particularly since

he was then free of any ejaculatory difficulty.

His general health was unimpaired, his

sexual desire was as strong as ever,

and he never experienced any erectile

difficulties. When seen one year after his

initial consultation, the problem had not changed.

REFERENCES

1. Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human sexual

inadequacy, Boston, 1970, Little, Brown and

Company.

2. McCarthy BW: Cognitive-behavioral

strategies and techniques in the treatment of early

ejaculation. In Leiblum SR, Rosen RC

(editors): Principles and practice of sex therapy: update for

the 1990s,

ed 2, New York, 1989, The Guilford Press, pp. 141-167.

3. Grenier G, Byers ES: Rapid ejaculation: a

review of conceptual, etiological, and treatment

issues, Arch Sex Behav 24:447-472,

1995.

4. Althof SE: Pharmacologic treatment of

rapid ejaculation. In Levine S (editor): Psychiatr

Clin North Am 18:85-94,

1995.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders, ed 4, revised, Washington, 1987, American

Psychiatric Association.

6. Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders, ed 4, primary care version, Washington, 1995,

American Psychiatric Association.

7. Masters WH, Johnson, VE: Homosexuality

in Perspective, Boston, 1979, Little, Brown

and Co.

8. Simon Rosser BR et al: Sexual difficulties,

concerns, and satisfaction in homosexual men:

an empirical study with implications for HIV

prevention, J Sex Marital Ther

23:61-73,1997.

9. Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE: Sexual

behavior in the human male, Philadelphia and

London, 1949, W.B. Saunders.

10. Laumann EO et al: The social

organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States,

Chicago, 1994, The University of Chicago

Press.

11. Spector IP, Carey MP: Incidence and

prevalence of the sexual dysfunctions, Arch Sex

Behav 19:389-408,

1990.

12. Godpodinoff ML: Premature ejaculation:

clinical subgroups and etiology, J Sex Marital

Ther 15:130-134,

1989.

13. Strassberg DS et al: The role of anxiety

in premature ejaculation: a psychophysiological model,

Arch Sex Behav 19:251-257, 1990.

14. Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human Sexual

Response, Boston, 1966, Little, Brown and Co.

15. De Amicis LA et al: Clinical follow-up of

couples treated for sexual dysfunction, Arch Sex

Behav 14:467-489,

1985.

16. Balon R: Antidepressants in the treatment

of premature ejaculation, J Sex Marital Ther

22:85-96, 1996.

17. Waldinger MD, Hengeveld MW, Zwinderman

AH: Paroxetine treatment of premature

ejaculation: a double-blind, randomized,

placebo-controlled study, Am J Psychiatry

151:1377-1379, 1994.

18. Mendels J, Camera A, Sikes C: Sertraline

treatment for premature ejaculation, J Clin

Psychopharmacology 15:341-346,

1995.

19. Haensel SM et al: Clomipramine and sexual

function in men with premature ejaculation

and controls, J Urol 156:1310-1315,

1996.

20. Zilbergeld B: Male sexuality, New

York, 1978, Bantam Books.

21. Kaplan HS: PE:how to overcome

premature ejaculation, New York, 1989, Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

22. Zilbergeld B: The new male sexuality,

New York, 1992, Bantam Books.

23. Semans JH: Premature ejaculation: a new

approach, South Med J 49:353-358, 1956.

24. Kaplan HS: The new sex therapy: active

treatment of sexual dysfunctions, New York, 1974,

Brunner/Mazel.

25. Apfelbaum B: Retarded ejaculation: a

much-misunderstood syndrome. In Leiblum SR,

Rosen RC (editors): Principles and

practice of sex therapy: update for the 1990s, ed. 2, New York,

1989, The Guilford Press, pp. 168-206.

26. Segraves RT: Antidepressant-induced

orgasm disorder, J Sex Marital Ther 21:192-201,

1995.

27. Crenshaw TL, Goldberg, JP: Sexual

pharmacology: drugs that affect sexual function, New York,

1996, W.W. Norton & Company.

28. Hawton K et al: Long-term outcome of sex

therapy, Behav Res Ther 24:665-675,

1986.

29. Rothschild AJ: Selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction:

efficacy of a drug holiday, Am J

Psychiatry 152:1514-1516, 1995.

30. Feiger A et al: Nefazodone versus

sertraline in outpatients with major depression: focus

on efficacy, tolerability, and effects on

sexual function and satisfaction, J Clin Psychiatry

57(Suppl 2):53-62, 1996.

31. Bartlik BD, Kaplan P, Kaplan HS:

Psychostimulants apparently reverse sexual dysfunction

secondary to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,

J Sex Marital Ther 21:264-271, 1995.

32. Reynolds RD: Sertraline-induced

anorgasmia treated with intermittent Nefazodone

(letter), J Clin Psychiatry 58:89,

1997.

33. Hershlag A, Schiff SF, DeCherney, AH:

Retrograde ejaculation, Hum Reprod 6:255-258,

1991.

34. Shaban SF, Seaman EK, Lipshultz LI:

Treatment of abnormalities of ejaculation. In

Lipshultz LI, Howards SS (editors): Infertility

in the male, ed 3, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby, pp.

423-438.

35. Benson GS: Erection, emission, and

ejaculation: physiological mechanisms. In Lipshultz

LI, Howards SS (editors): Infertility in

the male, ed 3, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby-Year Book,

Inc., pp. 155-172.

36. Yavetz H et al: Retrograde ejaculation, Hum

Reprod 93:381-386, 1994.

37. Oates RD: Nonsurgical treatment of

infertility: specific therapy. In Lipshultz LI, Howards

SS (editors): Infertility in the male, ed

2, St. Louis, 1991, Mosby - Year Book, Inc., pp

376-394.

38. Thorpe AC et al: Written consent about

sexual function in men undergoing transurethral

prostatectomy, Br J Urol 74:479-484,

1994.

39. Proctor KG, Howards SS: The effect of

sympathomimetic drugs on postlymphadenectomy

aspermia, J Urol 129:837-838, 1983.

40. Gilbaugh JH: Intrauterine insemination.

In Lipshultz LI, Howard SS (editors): Infertility in

the male, ed

3, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby, pp. 439-449.

41. Kulik FA, Wilbur R: Case report of

painful ejaculation as a side effect of Amoxapine, Am

J Psychiatry 139:234-235,

1982.

42. Aizenberg D et al: Painful ejaculation

associated with antidepressants in four patients, J

Clin Psychiatry 52:461-463,

1991.

43. Corriere JN Jr: Painful ejaculation due

to seminal vesicle calculi, J Urol 157:626, 1997.

44. Hakim LS, Oates AD: Nonsurgical treatment

of male infertility: specific therapy. In

Lipshultz LI, Howards SS (editors): Infertility

in the male, ed 2, St. Louis, 1997, Mosby.

45. Elliott S et al: Vibrostimulation and

electroejaculation: the Vancouver experience, J Soc

Obstet Gyncol Can 15:390-404, 1993.