CHAPTER 9

Low Sexual Desire In Women And Men

While something is known about

how to generate sexual desire—for example, creation of a new intimacy

in a conflicted relationship,

education in how to sexually stimulate one another, and provision of permission

to engage in sensuous

activity—the therapist knows far less than the patient thinks about how to

catalyze the appearance of

(sexual desire) . . . A sexual desire problem begins as a mystery to both

patient and doctor. . .

Levine,

19881

The Problem

A 35-year-old woman described a concern

that from the time of her marriage seven

years ago until the delivery of her 21⁄2

year old child, she became depressed and

irritable the week before her menstrual

periods and also lost all interest in anything

sexual during that time—thoughts, feelings,

or activities. This contrasted with her

“normal” sexual desire at other times,

which she felt were a rich part of her personal

life experience and relationship with her

husband. She was sexually active and

interested during her pregnancy but since

the delivery ceased to be interested in

anything sexual. Her husband was distressed

and she missed the sexual feelings

that had been so important to her in the

past.

A 45-year-old man was seen with his

41-year-old wife. They had been married for

17 years. Eleven years before, she

developed a bipolar illness and had periods of

depression and mania. She was sexually

involved with other men on an indiscriminate

and impulsive basis during her manic

episodes. The couple had no sexual

difficulties during the years of their

marriage before the onset of her illness but the

lack of sexual interest by the husband had

become increasingly evident during the

previous decade. His loss of sexual desire

did not, for example, extend to looking

at other women he considered attractive nor

to masturbating several times each

week when he was alone. He could not

explain his diminished sexual interest in his

wife. He clearly proclaimed his continuing

love for her and his feeling that her

sexual liaisons with other men held little

meaning.

Terminology

Various words and phrases are

used as synonyms for sexual desire, including libido,2

interest, drive, appetite, urge,

lust, and instinct. Low sexual desire is variously referred

to as: “sexual apathy,” “sexual

malaise,” and “sexual anorexia”3 (p. 315).

For consistency

with the DSM system and the

wording in most literature sources, the term “sexual

desire” is used here.

Problems In The Definition Of Sexual Desire

Sexual desire disorders are

enigmatic and difficult to know how to approach therapeutically,

and the entire concept of sexual

desire provokes some critical questions,

as follows:

• What is “normal” sexual desire?

Is it on a bell-shaped curve where, like

height or weight, some people

have a lot, some people have a little, and

most people are in the middle?

Kinsey and his colleagues attempted to

answer this question in saying “.

. . there is a certain skepticism in the

profession of the existence of

people who are basically low in capacity

to respond. This amounts to

asserting that all people are more or less equal

in their sexual endowments, and

ignores the existence of individual

variation. No one who knows how

remarkably different individuals may

be in morphology, in physiologic

reactions, and in other psychologic

capacities could conceive of

erotic capacities (of all things) that were

basically uniform throughout a

population”4 (p. 209). Zilbergeld and

Ellison suggest that “To say that

there is more or less of something

. . . necessitates a standard of

comparison . . . But there are no

standards of sexual desire; we do

not know what is right, normal, or

healthy, and it seems clear that

such standards will not be forthcoming”5

(p. 67). In a clear and

practical, but somewhat contrary, statement,

LoPiccolo & Friedman offered

the view that “In actual clinical practice

. . . most cases [of sexual

desire disorders] are so clearly beyond

the lower end of the normal curve

that definitional issues become

moot”6 (p.

110).

• Is sexual desire the same for

men as for women? Bancroft thought not.

He speculated “that there may be

a genuine sex difference in hormonebehavior

relationships, with men showing

consistent androgen/behavior

relationships across studies

(particularly androgen/sexual interest relationships),

whereas in women ‘the evidence

for hormone-behavior relationships

is much less consistent, and

often seemingly contradictory’.”7

• Does one measure sexual desire

subjectively (by thoughts and feelings),

or objectively (by actions), or

both? Considering only sexual actions or

behavior ignores the fact that,

sometimes, nonsexual motives govern

sexual activity. For example, a

person might engage in sexual

activity to please a partner,

quite apart from satisfying their own

feelings of sexual desire.

• Should sexual desire disorders

be classified as sexual dysfunctions

as they are in DSM-IV?8

Are they really on the same level

as, for example, physiological

difficulties such as erection and

orgasm problems, or do they

represent a totally different category

of sexual disorders? Some

patients distinguish the two by

Some patients explain that (1) erection

and orgasm problems are like automobile

engine troubles and (2) that desire

difficulties are more like a problem with

the starter in that the engine simply

does not turn over.

|

using the ubiquitous North

American symbol of the car, explaining that

erection and orgasm problems are

like engine troubles, whereas a desire

difficulty is more like a problem

with the starter in that the engine simply

does not turn over.

Classification Of Sexual Hypoactive Desire

Disorders

Disorders of sexual desire are

classified in DSM-IV as “Sexual Desire Disorders.”

(SDD).8 This

category contains two conditions:

• Hypoactive Sexual Desire

Disorder (HSDD or HSD)

• Sexual Aversion Disorder (SAD)

DSM-IV-PC summarizes the criteria

for the diagnosis of HSD as: “persistently or

recurrently deficient (or absent)

sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity that

causes marked distress or

interpersonal difficulty” (p. 115), and criteria for SAD as:

“(A) persistent or extreme

aversion to, and avoidance of, any genital contact with

a sexual partner, causing marked

distress or interpersonal difficulty” and “(B) the

disturbance does not occur

exclusively during the course of another mental disorder

. . .”9(p.

116).

The separation of SDDs into two

groupings began with DSM-III,10 and while

Sexual

Aversion Disorder has received

some attention in the literature, it has not been the

subject of much research.9

HSD, the focus of this chapter,

is often not clinically distinguished from other

problems with sexual function

seen in primary care settings. Separating the two phenomena

and determining the chronology of

appearance (i.e., whichever developed

first) may be extremely important

clinically in considering etiology and treatment.

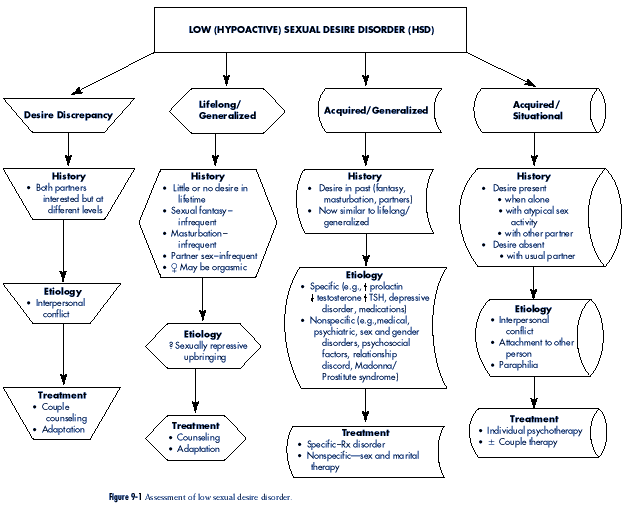

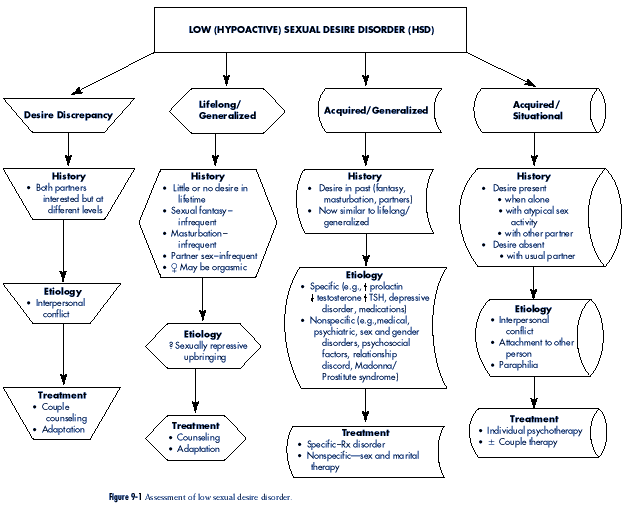

The assessment of low sexual

desire is outlined in Figure 9-1.

Subclassification Of Hypoactive Sexual Desire

Disorders: Descriptions

Sexual Desire Discrepancy

Although not categorized as a

“disorder” in DSM-IV8 or DSM-IV-PC,9

one of the ways that a sexual

desire problem becomes apparent is when

two partners are sexually

interested but not at the same level. Identical

levels of sexual desire in sexual

partners rarely occur. More usual is the

fact that both are interested but

one person is more interested than the

other. Couples generally “work

out” different sexual appetites by mutual

acceptance and compromise (or

“negotiation”). “Such discrepancies have much in common

with other relationship

difficulties—how to raise children, how often to dine out

or have company in, where to

spend the vacation, etc. . .”5 (p. 68).

Occasionally, a desire

discrepancy becomes a problem so that it results in a concern

brought to a health professional.

Couples sometimes focus on sexual problems as a way

of obscuring other tensions, but

then the history of the couple relationship should

indicate a change in sexual

interest. If the history of discrepancy dates from early in

the relationship (not necessarily

the beginning when “limerance” (see p. 182) may be

prominent), one has to ask: why

is it that these two people are unable to do what most

Identical levels of sexual desire in two

people rarely occur. Usually both are

interested but one person is more

interested

than the other. Couples generally

“work out” different sexual appetites by

mutual acceptance and compromise (or

“negotiation”).

|

couples seem to do, that is,

accept one another and compromise? The search for the

answer should begin on a primary

care level.

A couple in their mid-50s wanted assistance

because of a difference in sexual desire.

In talking with them initially together,

they candidly said that this discrepancy

existed since they married 30 years ago and

both agreed that her desire always had

been greater than his. When seen alone, he

elaborated on his initial statements by

saying that, indeed, there had always been

a difference in the amount of sexual

activity that each preferred. However, he

had not been candid with her in the past

about particular sexual practices which he

fantasized about and, in fact, had enjoyed

with other partners before they married. He

anticipated resistance from her in telling

her now, but, in fact, found the opposite.

The quality of their sexual experiences

improved greatly in the following months,

even though the quantity changed

little. When seen in follow-up six months

later, the issue of a sexual desire discrepancy

had not disappeared but there was much less

concern.

Lifelong and Generalized Absence of Sexual Desire

From a clinical viewpoint, this

particular form of sexual desire disorder seems to be

found more frequently in women

than men. The patient shows little, if any, indication

of sexual appetite in thought,

feeling, or action, now or in the past. Sexual experiences

with a partner occur uncommonly

and usually on the initiative of the other person.

The patient participates out of

recognition of the partner’s sexual needs rather than a

fulfillment of her own. Vaginal

lubrication and orgasm may occur but these are not

considered momentous.

Masturbation to the point of orgasm might also occur occasionally

but without enthusiasm. The

motivation for masturbation is often other than

sexual, such as wanting to

diminish feelings of anxiety or as an aid to inducing sleep.

Sexual dreams and fantasies are

nonexistent and the patient may describe a response to

romantic stories

in books or movies but not a response to depictions of sexual activity

in either. During adolescence,

the women thought of herself as different from girlfriends

in not being interested in boys,

easily fending off sexual propositions, and

hardly ever thinking about

anything sexual. She sums up her present status by saying

that she could live the rest of

her life without “sex,” and may add that the only reason

she is seeking consultation is

that, implicitly or explicitly, the viability of her relationship

is in jeopardy.

A 27-year-old woman was engaged for six

months and considering marriage. She

was concerned about her lack of sexual

interest and wondered if there was something

wrong with her. Primarily, she wanted to

know if anything could be done to

alter her present sexual situation. She

experimented sexually to the point of intercourse

on two occasions in the past and had become

sexually involved with her

husband-to-be shortly after they met. It

was apparent that she found these experiences

to be neither pleasurable nor repellent.

As a teenager she wondered what other girls

found so interesting about boys.

Sexual urges were not present then or

since. Her interest and energy was directed

toward scholastic studies, at which she

excelled. She eventually became a successful

lawyer, specializing in corporate law.

In a separate interview, her fiancee

indicated that while sexual experiences were

important to him, he was not willing to

forsake the relationship because of this

difficulty. In the one-year follow-up

interval, they married, and while her sexual

desire had not changed, she was active from

time-to-time as she sensed an increase

in his sexual needs. He preferred more sexual

activity but he felt as though they

had adapted in other ways.

Acquired and Generalized Absence of Sexual Desire

The major difference between the acquired

and generalized form of a sexual desire disorder

and the lifelong and

generalized form is that the present status represents a considerable

change from the past. In the

acquired and generalized form of HSD, the

patient describes having been

sexually interested and active in the past, but relates

much the same feelings about

“sex” in the present as the person with the lifelong form.

That is, she says that in

contrast to the past she does not now have sexual thoughts,

fantasies, or dreams and is only

infrequently sexually active with a partner or by herself

through masturbation. She may

also say that her interest level is such that life without

“sex” does not represent a

problem to her directly, although the opposite is usually true

for her partner.

A 47-year-old woman, married for 23 years,

described feeling diminished sexual

desire since her hysterectomy five years

earlier. She never experienced sexual difficulties

before. Medical history revealed that she

had the surgery because of excessive

menstrual bleeding associated with

fibroids: her ovaries were also removed and

she was on hormone replacement therapy (not

including testosterone) since then.

Intercourse continued after her

hysterectomy but what she liked most was the

closeness and affection that was part of

this experience. She had little problem

becoming vaginally wet when stimulated but found

that intercourse ceased to be

sexually gratifying. She was regularly

orgasmic in the past but was not so in the

present. Vaginal pain with intercourse

rarely occurred but when it did it was

momentary and disappeared with change in

position. Testosterone was given

because of her ovariectomy (see below) and

she found that, as a result, her sexual

desire was substantially enhanced.

Acquired and Situational Absence of Sexual Desire

The most striking feature that

differentiates a situational desire disorder from one that is

generalized is

the continued presence of sexual desire. The sexual feelings that do exist

in the present occur typically

when the person is alone and manifest either in thought

and/or action (through

masturbation), rather than in sexual activity with the patient’s

usual partner. The patient

characteristically states that there are sexual themes in his or

her thoughts and fantasies, and

perhaps attraction to people other than the usual partner.

Sexual activity with their

partner is considerably less frequent than sexual thoughts

in general. In addition, the

present level of sexual activity often represents a substantial

change from the beginning of the

relationship when the frequency was much greater.

However, as one reviews other

relationships in the past, it may become evident that

the same sequence of events

occurred before. That is, the interviewer might discover

that there was a pattern of

initial sexual interest in a partner, followed by a gradual

diminution of sexual interest,

resulting in relative sexual inactivity.

The 24-year-old wife of a 29-year-old man

described a concern about her husband’s

lack of sexual attention to her. They were

married for two years. When they first

met, she was relieved and pleased to find

that she did not have to fend him off

sexually and that he was quite prepared to

proceed at her pace. When asked about

their premarital sexual experiences with

one another, she related having had intercourse

on many occasions but also thought that she

was probably more sexually

interested than he.

After their marriage, the frequency of

sexual events dropped precipitously. Her

overtures were regularly turned aside, to

the point where she stopped asking. She

wondered whether his lack of interest was a

result of her becoming less sexually

appealing to him. When seen alone it became

clear that far from being sexually

neutral, and unknown to his wife, he

masturbated several times each week while

looking at magazine pictures of nude women.

Significant issues in the history of his

family-of-origin suggested that psychotherapy

would be the preferred treatment for this

man and he was subsequently

referred to a psychiatrist. He accepted

this outcome but when they were seen six

months later in follow-up he had a myriad

of reasons for not having followed

through on the referral. She was

disappointed at the turn of events, but not surprised.

When she then voiced her thoughts about

leaving him, he became more

determined to put aside his reticence to

seek assistance.

Epidemiology Of Hypoactive Sexual Desire

Disorder

Lack of sexual desire, or sexual

disinterest, is probably the most common

sexual complaint heard by health

professionals. Studies of the frequency of

sexual disorders tend not to

distinguish the different subcategories of

desire disorders, so that

separation into syndromes which are lifelong,

acquired, situational or

generalized are often based more on clinical

experience than research.

The survey completed by Laumann

and his colleagues was particularly

revealing about the subject of

sexual interest in the general population (as distinct

from specialty clinics).12

Interviewers asked respondents: “During the last 12 months

has there ever been a period of

several months or more when you lacked interest in

Lack of sexual desire, or sexual

disinterest,

is probably the most common sexual

complaint heard by health professionals.

|

having sex?” Overall, 33% of

women and 16% of men answered ‘yes.’

The most striking data concerning

women revealed that 40% to 45%

who were separated, black, did

not finish high school, and “poor”

answered positively (i.e., lacked

sexual interest). The equivalent data

concerning men were that 20% to

25% who were in the age group

50-59, never married, black, did

not finish high school, and “poor” also

answered positively. Positive

responses were also related to physical

health: women and men in “fair”

health, 42% and 25% respectively.

Fifty eight percent of women in

“poor” health, reported lacking sexual interest. These

numbers provoke one to think

about the definition of “normal” sexual interest and the

apparent role of social,

educational, and health factors in influencing sexual desire.

Frank and her colleagues’

impressive study of “normal” couples found a rate of sexual

“disinterest” almost identical to

the overall figures reported by Laumann et al12:

35% of

wives and 16% of husbands.13

In one specialty clinic, the

frequency of presentation of low-desire problems rose

from about 32% of couples in the

mid 1970s to 55% in the early 1980s6 (p. 112).

In

these same couples, the sex ratio

changed so that in the mid-70s, the woman was the

identified patient about 70% of

the time; in the early 80s, the man was the focus of

concern in 55% of cases. The

authors summarized the reason for this shift as follows:

“Women’s greater comfort with

their own sexuality allows them to put sufficient pressure

on their low-drive husbands to

get the couple into sex therapy; this was not true

until the woman’s movement

legitimized female sexuality.”

In a report on the frequency of

HSD in a population recruited for a study of sexual

disorders generally, 30% of the

men had HSD as a “primary” diagnosis.14 The same

authors described the frequency

in women as similar to that reported by others: between

30% and 50%, although they found

the figure to be 89% in their own study. Over one

third of the women and almost one

half of the men with a “primary” diagnosis of HSD

had another sexual disorder as

well. The authors concluded the following:

1. HSD was much more common in women

than men

2. Men with HSD were

significantly older than women

3. Desire disorders usually

coexist with other sexual dysfunctions

Little empirical information

exists on the epidemiology of specific HSD syndromes.

Among men, Kinsey and his

colleagues described 147 men (from about 12,000 interviewed)

as “low-rating” (defined as under

36 years of age and whose “rates” [of sexual

behavior] averaged one event in

two weeks or less4 (p. 207). Another group of

men,

about half the number, were

described as “sexually apathetic” in that “they never, at any

times in their histories, have

given evidence that they were capable of anything except

low rates of activity” (p. 209).

About 2% of women interviewed (of almost 8000) had

never by their late 40s

“recognized any sexual arousal, under any sort of condition”12

(p. 512).

On the basis of experience in

clinical settings that specialize in the assessment and

treatment of sexual problems, the

lifelong and generalized form of HSD seems very

unusual; the acquired and generalized

form appears to be the most common among

women. Within men who present

with HSD, the acquired and situational form seems

to be the most usual.

Interviewers asked respondents: “During

the last 12 months has there ever been

a period of several months or more

when you lacked interest in having

sex?” Overall, 33% of women and 16%

of men answered ‘yes.’

|

Components Of Sexual Desire

Attempts to understand the nature

of sexual desire (other than desire disorders) have

been elusive throughout history. In

modern times, Levine conceived of sexual desire as

having three parts16:

1. Sexual drive: “a

neuroendocrine generator of sexual impulses [that is] . . . testosterone-

dependent . . .”

2. Sexual wish: “a

cognitive aspiration [that] . . . emphasizes the purely ideational

aspect of sexual desire . . . The

most important element . . . is the willingness

to have sex [which, in turn] . .

. is a product of psychological motivation.”

(An example of a reason why a

person would be sexually willing, is to feel connected

to another person and less alone.

An example of the opposite is, because

the person may not yet like

anyone enough.)

3. Sexual motive: a factor

“that depends heavily on present and past interpersonal

relationships. [And which] . . .

seems to be the most important element of

desire under ordinary

circumstances” (examples of contributors to sexual motivation

include the quality of the

nonsexual relationship and sexual orientation)

Hormones And Sexual Desire

Biological factors represent one

vital component in the understanding of sexual desire

generally (in contrast to

disorders of sexual desire). Within the biological domain,

knowledge of the hormonal

influence on sexual desire is clearly critical—if for no

other reason than that many

people in the general population firmly believe that alterations

in hormones explain changes in

sexual behavior. Although this relationship is

unequivocally true in

subprimates, this view minimizes the huge impact of social learning

in humans. The enormous quantity

of literature on the significance of hormones on

sexual desire in men and women

was comprehensively reviewed by Segraves, from

which much of the information

included immediately below was taken.17

Men

Much of the evidence concerning

the connection between sexual desire

and hormones in men derives from

situations that involve decreased

androgens resulting from surgical

and chemical castration, aging, and

hypogonadal states. Surgical

castration results in a typical sequence of

changes: a sharp drop in sexual drive,

subsequent loss of the ability to

ejaculate, and then a lessening

of sexual activity. Regarding the effect

of testosterone loss on erections

(see Chapter 11), “It appears that

erectile problems are secondary

to a decrease in libido and not due to

a specific effect of androgen

withdrawal on the erectile mechanism”17

(p. 278). Chemical castration

mimics this lack of effect on erections.

In a study of aging,

testosterone, and sexual desire, Segraves observed

that while there is “ . . . a

strong relationship between aging and

libido, the relationship between

libido and androgen activity (in aging

men) was low, suggesting that

nonendocrinological factors may explain

Surgical castration results in a typical

sequence of changes: a sharp drop in

sexual drive, subsequent loss of the

ability to ejaculate, and then a lessening

of sexual activity.

“It appears that erectile problems are

secondary to a decrease in libido and

not due to a specific effect of androgen

withdrawal on the erectile mechanism”17

(p. 278).

|

the decline in sexuality with

aging”17(p. 281). Examples of nonendocrine factors

include:

• Marital boredom

• Diminished partner

attractiveness

• Chronic illness

In hypogonadal states, one can

witness the effect of testosterone deficiency

and subsequently the changes that

take place with recovery when

a replacement hormone is given.

“The clinical literature is consistent in

demonstrating a marked reduction

in libido and sexual activity in

untreated hypogonadal men”17(p.

281). To the extent that the provision

of androgens is successful in

hypogonadal men, evidence strongly suggests

a primary effect on sexual desire

rather than on erectile capacity.

The “impotence” that is seen in

hypogonadal men can be explained as

“performance anxiety” superimposed

on a biogenic desire disorder.

Studies of the treatment of

hypogonadal men show that the sexual

benefits of replacement

testosterone disappear as the normal range of

blood values is approached,

indicating the clinically vital suggestion

that treating men who have normal

testosterone levels for problems

relating to sexual responsivity

is likely to be ineffective. In fact, studies

of men who have normal levels

of testosterone but who are given an extra

amount for the treatment of

sexual difficulties suggest that “ . . . the

effects are subtle and of small

magnitude if they exist at all”17 (p. 284).

Elevated prolactin levels also

reveal significant information about

hormones and sexual desire in men

(and women). One study demonstrates

the futility of attempting to

strictly separate sexual problems of

“organic” and “psychogenic”

etiology.18 All of the hyperprolactinemic

men described difficulties with

sexual desire, as well as erection and/or

ejaculation dysfunction. Of

particular significance is that some of the

sexual problems of the men in

this group appear as situational difficulties

(e.g., dysfunction exacerbated by

psychological factors, which

improved at times of enhanced

arousal). Furthermore all of the men experienced

some improvement with sex therapy,

which was provided before the hyperprolactinemia

was discovered.

Women

Two areas of investigation help

in understanding the influence of hormonal factors on

sexual desire in women:

• The impact of endogenous

hormones (e.g., changes during the menstrual

cycle and with menopause)

• The effect of exogenous

hormones (e.g., oral contraceptives)

The possibility that sexual

interests change during the menstrual cycle precipitated

attempts to discern a

relationship between estrogens and progesterone and sexual

activity. A correlation has not

been found but some evidence shows that average serum

testosterone levels across all

phases are related to sexual responsivity17 (p.

290).

The impotence that is seen in hypogonadal

men can be explained as “performance

anxiety” superimposed on a biogenic

desire disorder.

An attempt to strictly separate sexual

problems into “organic” and “psychogenic”

etiology may be an exercise in

futility. In one study, all of the men with

hyperprolactinemia described difficulties

with sexual desire, erection, and/or

ejaculation dysfunction. Of particular

significance is that some of the sexual

problems appeared as situational

difficulties.

Also, all of the men experienced

some improvement with sex therapy,

which was provided before the hyperprolactinemia

was discovered.

Studies of men who have normal levels

of testosterone but who are given an

extra amount for the treatment of sexual

difficulties suggest that “. . .the

effects are subtle and of small magnitude

if they exist at all”17

(p. 284).

|

Changes in sexual desire

associated with menopause have also been investigated.

“A minority of women report some

decline in sexual activity . . .”17 (p. 295)

but this

could relate to factors other

than libido (e.g., health and attractiveness of the woman’s

partner). Some

psychophysiological studies report little or no change in subjective

sexual arousal of postmenopausal

women. Again, in contrast to naturally occurring

menopause, Sherwin and her

colleagues demonstrated that diminished sexual

desire and sexual fantasy

accompanies early menopause resulting from surgical removal

of a woman’s ovaries.19

The explanation for this observation appears to be decreased

testosterone associated with

ovariectomy. She also found that in about 50% of

instances of naturally occurring

menopause, the ovary continues to secrete testosterone;

in the other 50%, testosterone

secretion is negligible. She suggests the inclusion

of testosterone in replacement

hormones after a surgically induced menopause, and

also that, when diminished sexual

desire occurs coincidentally with naturally occurring

menopause, it might be reasonable

to add testosterone to an estrogen replacement

regimen (see “Treatment of

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder” below).20

On the subject of the impact of

oral contraceptives on sexual desire, “The evidence

is unclear, but it does not

suggest that [they] have a marked effect on libido apart from

other side effects” such as

nausea and dysphoria17 (p. 292). Segraves

suggests the following

guidelines when faced with a

patient using oral contraceptives and complaining

of low sexual desire:

1. If diminished sexual desire

and other side effects persist beyond the second

month of use, it might (by

implication) be reasonable to change the preparation

2. If diminished sexual desire is

a solitary complaint and began after the initiation

of oral contraceptive use, it

might be sensible to have a trial period off

medications

3. If sexual desire returns “off

medications,” suggest a different drug

Etiologies Of Hypoactive Sexual Desire

Disorder

When considering sexual desire

difficulties (rather than sexual desire),

it seems best to think of these

problems as representing a “final common

pathway”6 (p.

116). The linguistic homogeneity implied by the specific

diagnosis of “Hypoactive Sexual

Desire Disorder” covers a great deal of

etiological heterogeneity. There

is no reason to assume that (1) HSD in

men arise(s) from the same

source(s) as in women, (2) a lifelong pattern

is caused by the same problems as

those which are acquired, or (3) a

situational disorder has the same

genesis as the other two. Although

HSDs in men and women are now

usually considered separately, the

same cannot always be said of

other subcategories.

The following were noted in a

descriptive examination of differences

in men and women seen in a “sex

clinic” with a sexual desire complaint21:

1. Men were described as

significantly older (50 years old versus 33)

2. Women reported a higher level

of psychological distress, although both groups

focused more on the sexual desire

concern

When considering sexual desire difficulties

(rather than sexual desire), it seems

best to think of these problems as

representing

a “final common pathway”6

(p. 116). The linguistic homogeneity

implied by the specific diagnosis of

“Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder”

covers a great deal of etiological

heterogeneity.

|

3. Men’s desire difficulties

seemed less affected by relationship discord or dissatisfaction

4. Women reported more domestic

stress

Generalized HSD

Biologically related studies of

HSD undertaken by Schiavi, Schreiner-Engel, and their

colleagues are at the forefront

of investigations into the etiologies of HSD and represent

important exceptions to the

heterogeneity described above. A controlled investigation

was completed on a group of men

who demonstrated a “generalized and persistent lack

of sexual desire” but who were

otherwise healthy.22 The HSD men were found to

have

significantly lower total plasma

testosterone levels when measured hourly throughout

the night. (The determination of

free testosterone did not show differences between the

HSD men and the controls). When

Nocturnal Penile Tumescence (NPT) comparisons

were made between the HSD men who

did and did not have additional erectile difficulties,

those who did showed a marked

depression in NPT activity when compared to

controls in duration, frequency,

and degree. The authors speculated that low sex drive

results in impaired NPT or that

both result from some central biological abnormality.

A companion study of women with

generalized HSD (lifelong [38%] and acquired)

who were otherwise healthy found

no significant differences from controls on hormonal

measures (including testosterone)

determined over the menstrual cycle.23 “It is

impressive that these two groups

of women, who differed so markedly in their levels

of sexual desire, had endocrine

milieus so similar.” The authors summarized by saying

that this and other studies

failed “to provide convincing evidence that circulating testosterone

is an important determinant of

individual differences in the sexual desire of

eugonadal women.”

Medical Disorders and HSD

Many medical conditions are

associated with a loss of sexual desire. These are summarized

in Box 9-1.

As described in Chapter 8, sexual

problems that are in general associated with medical

conditions arise from a variety

of sources. A loss of sexual desire in particular can

be a result of biological,

psychological, or social and interpersonal factors24 (pp.

356-366). Examples of biological

factors include the following:

1. Direct physiological effects

of the illness or disability

2. Direct physiological effects

of medical treatment and management (e.g., steroid

treatment of rheumatoid

arthritis)

3. Physical debilitation

4. Bowel or bladder incontinence

Examples of psychological factors

include:

1. Adopting the “patient” role

(as an asexual person)

2. Altered body image

3. Feelings of anxiety,

depression, and anger

4. Fears of death, rejection by a

partner, or loss of control

5. Guilt regarding behavior

imagined as the cause of a disease or disability

6. Reassignment of priorities

Box 9-1

Common Medical Conditions That May Decrease Sexual Desire

A DISEASES THAT CAUSE

TESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY STATES IN

MALES:

castration, injuries to the testes,

age-related atrophic testicular degeneration, bilateral

cryptorchism, Klinefelter’s syndrome,

hydrocele, varicocele, cytotoxic chemotherapy,

pelvic radiation, mumps orchitis,

hypothalamic-pituitary lesions, Addison’s disease, etc.

Conditions requiring anti-androgens drugs,

e.g., prostate cancer, antisocial sexual

behavior, etc.

IN FEMALES:

Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy,

adrenalectomy, hypophysectomy, cytotoxic chemotherapy,

hypothalamic-pituitary lesions, Addison’s

disease, androgen insensitivity

syndrome, etc.

Conditions requiring anti-androgen drugs,

e.g., endometriosis, etc.

B CONDITIONS THAT CAUSE

HYPERPROLACTINEMIA:

pituitary prolactin-secreting adenoma,

other tumors of the pituitary, hypothalamic

disease, hypothyroidism, hepatic cirrhosis,

stress, breast manipulation, etc., and conditions

requiring Prl raising medication, e.g.,

depression, psychosis, infertility, etc.

C CONDITIONS THAT DECREASE

DESIRE VIA UNKNOWN MECHANISMS:

hyperthyroidism, temporal lobe epilepsy,

renal dialysis, etc.

D CONDITIONS THAT CAUSE ORGANIC

IMPOTENCE (Indirect cause of low

sexual desire in men):

diabetes mellitus, arteriosclerosis of

penile blood vessels, venus leak, penile muscular

atrophy, Peyronie disease, Lariche’s

syndrome, steal syndrome, sickle cell disease, priapism,

injury to penis, etc.

E CONDITIONS THAT CAUSE

DYSPAREUNIA (Indirect cause of low sexual

desire):

IN FEMALES:

urogenital estrogen-deficiency

syndrome—normal age-related menopause, surgical

menopause, chemical menopause, irradiation

of ovaries; endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory

disease, vaginitis, herpes, vaginismus,

cystitis, etc.

IN MALES:

herpes, phymosis, post-ejaculatory

syndrome, etc.

F ALL MEDICAL CONDITIONS THAT

CAUSE CHRONIC PAIN, FATIGUE,

OR MALAISE (Indirect cause of

low desire):

arthritis, cancer, obstructive pulmonary

disease, chronic cardiac and renal insufficiency,

shingles, peripheral neuropathy, trigeminal

neuralgia, chronic infections, traumatic injuries,

etc.

(Modified from Kaplan HS: The sexual

desire disorders, New York, 1995, Brunner/Mazel, p. 286. Reprinted with

permission.)

|

Examples of social and

interpersonal factors include:

1. Communication difficulties

regarding feelings or sexuality

2. Difficulty initiating “sex”

after a period of abstinence

3. Fear of physically damaging an

ill or disabled partner

4. Lack of a partner

5. Lack of privacy

Gynecologic and urologic

disorders have a particular association with HSD. Testicular

and ovarian disorders can have

direct effects on sexual desire (see previous section

in this chapter on “Hormones and

Sexual Desire” and “Treatment of Hypoactive

Sexual Desire” below). Indirect

effects on sexual desire can also result from structural

disorders occurring in both body

systems. Given the fact that one of the major functions

of both the gynecologic and

urologic systems is sexual, it is hardly surprising that

when one function goes awry,

sexual function goes awry as well. This may easily result

in the patient being discouraged

and experiencing a concomitant (but secondary) loss

of sexual desire.

Hormonal Disorders and HSD

(See previous section in this

Chapter on “Hormones and Sexual Desire” and “Treatment

of Hypoactive Sexual Desire

Disorder” below.)

Psychiatric Disorders and HSD

The relationship between

psychiatric disorders and loss of sexual desire has not been

so carefully studied as loss of

sexual desire with medical disorders. On a clinical basis,

it seems that the association

between the two is exceedingly frequent. Of all psychiatric

disorders in which a loss of

sexual desire is an accompaniment, depression has

unquestionably received most

attention. Other aspects of depression have been scrupulously

scrutinized in the past but this

has been only recently true of its sexual ramifications.

The twin issues of depression and

sexual desire were carefully studied

in 40 depressed men before and

after treatment that did not include antidepressant

drugs (thus avoiding the

potentially confusing factor of the

effect of medications).25

Contrary to the expected diminution in sexual

desire, the authors found that

the initial level of sexual activity engaged in

by the subjects was not different

than the controls. The sexual behavior of

those subjects whose depression

remitted with treatment, did not change,

but what was altered was

the level of satisfaction derived from sexual experiences.

They concluded that“ . . . the

traditional notion of loss of sexual

interest in depressed outpatients

is not manifested behaviorally, but rather

reflects the depressed patient’s

cognitive appraisal of sexual function as

less satisfying and pleasurable.”

When subjects who did not remit, or only

partially remitted, were included

in the analysis, there was a “modest”

improvement in the level of

sexual activity and “drive.” The authors found the variability

of sexual function in depressed

men in this study particularly interesting.

Schreiner-Engel and Schiavi

looked at the association of psychiatric disorders and

low sexual desire from a

different perspective and found that HSD patients (men and

the sexual behavior of the subjects

whose depression remitted with treatment

did not change but what was

altered was the level of satisfaction

derived from sexual experiences.

Investigators

included that “. . . the traditional

notion of loss of sexual interest in

depressed outpatients is not manifested

behaviorally, but rather reflects the

depressed patient’s cognitive appraisal

of sexual function as less satisfying and

pleasurable.”25

|

women) had significantly elevated

lifetime prevalence rates of affective disorder compared

to controls.26

None of the patients or controls had a diagnosable illness at the

time of the study and there were

no differences found in lifetime diagnoses of anxiety

or personality disorders. In 88%

of the HSD men, and all of the HSD women, loss of

sexual interest occurred at the

time of, or following, the onset of the initial episode of

depression. The authors

speculated on the possibility that central monoaminergic processes

were involved in both HSD and

depression.

Medications and HSD

The influence of drugs looms

large among the various biological factors that can negatively

influence sexual desire. This

subject has been reviewed in detail by Segraves who

acknowledges the limitations in

information that often exists,3 such as:

1. Bias due to dependence on case

reports and questionnaire studies

2. Inconsistent use of

terminology

3. A focus on the sexual function

of men (and relative neglect of women)

4. Reliance on volunteered

(rather than requested) information about sexual sideeffects

5. Lack of clarity about effects

on different phases of the sex response cycle

Drugs that are said to cause HSD

are noted in Appendix III and Box 9-2.

Drug-related information seems to

change more rapidly than any other material in

health care; thus new drugs are

promoted for old diseases and side-effects of older

drugs become more apparent. The

result of the rapid pace of change in information

about sexual side effects of

drugs is the requirement that health professionals remain

informed. An example of this

change is the appearance of a negative impact on sexual

desire of the Selective Serotonin

Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs).27

Other Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders and HSD

Other sexual and gender identity

disorders may be associated with a loss of sexual

desire. Of particular

significance is the simultaneous occurrence of another sexual dysfunction

that may be a cause or a result

of HSD. Determining the order of appearance

of the two problems is crucial.

If the other sexual function difficulty preceded the loss

of sexual desire, successful

treatment of the former would likely result in disappearance

of the latter.

A couple in their late 20s and married for

five years was referred because the

woman was sexually disinterested. Detailed

inquiry of this complaint revealed that,

unknown to her husband, she regularly

fantasized about sexual activity and masturbated

to the point of orgasm using a vibrator

several times each month. Her lack

of sexual desire was specific to sexual

activity with her husband and dated from

about two years before. In the first three

years of their marriage, both freely initiated

sexual activity and she usually become

highly aroused but never reached the

point of orgasm. She became physically and

psychologically uncomfortable, so

much so that she decided that “it was

better not to start what (she) couldn’t finish.”

By her own description, she refused to

become aroused at the beginning of their

sexual encounters by deliberately “turning

off” her sexual desire. Her husband was

relieved to discover her interest in

masturbation and that she was orgasmic. He was

eager to find ways in which that experience

could be incorporated into their lovemaking

as a couple.

Box 9-2

Commonly Used Pharmacologic Agents That May Decrease Sexual

Desire

A ANTI-ANDROGEN DRUGS*:

Cyproterone* and Depo-provera* (for sex

offenders), Flutamide* (for prostate cancer

in men, virilizing syndromes in women,

precocious puberty in boys, etc.), Lupurin,* a

gonadotropin releasing hormone analog (for

prostrate cancer, used together with Flutamide,

also for endometriosis in women); cytotoxic

chemotherapeutic agents* (Adriamycin,

Methotrexate, Cytotoxin, Fluorouracil,

Cisplatin, etc.)

B PSYCHOACTIVE DRUGS:

1. Sedative-Hypnotics: loss of

desire dose-related: in low doses, disinhibition may cause

increase in desire; high doses and chronic

use reduce desire. Alcohol; Benzodiazepines

(Valium, Ativan, Xanax, Librium, Halcion,

etc); Barbiturates (phenobarbital, amytal,

etc.); Chlorol hydrate, Methaqualone, etc.

2. Narcotics* (Heroin, Morphine,

Methadone, Meperidine, etc.)

3. Anti-Depressants: (Dopamine

blocking and serotonergic) SSRIs* (Prozac, Zoloft,

Paxil); Tricyclics (Tofranil, Norpramin,

Amitriptyline, Aventyl, Clomipramine*); MAOIs*

(Nardil, Marplan), Lithium carbonate, Tegretol.

4. Neuroleptics (increase Prl): Phenothiazine

(Thorazine,* Thioridazine) Prolixin,* Stelazine,

Mellaril, etc.); Haldol,* Sulpiride.*

5. Stimulants: loss of desire is

dose-related: low, acute doses may stimulate libido; high

doses and chronic use reduce sex drive.

(Dexadrine, Methamphetamine, Cocaine).

C CARDIAC DRUGS:

1. Antihypertensives: (Hydrochlorothiazide,*

Chlorthalidone,* Methyldopa,*

Spironolactone,* Reserpine,* Clonidine,

Guanethidine,* etc.)

2. Cardiac Drugs: Beta adrenergic

blockers* (Inderal, Atenolol, Timolol, etc.); Calcium

blockers** (Nifedipine, Verapramil, etc.)

D DRUGS THAT BIND WITH

TESTOSTERONE:

1. Tamoxifen, Contraceptive agents, etc.

E MISCELLANEOUS DRUGS: Cimetidine*

(for peptic ulcer); Pondimin* (serotonergic

appetite suppressor); Diclorphenamine,

Methazolamide (for glaucoma); Clofribrate,

Lovastatin (anticholesterol); Steroids

(chronic use for inflammatory conditions),

(Prednisone, Decadron, etc.).

*All the drugs listed have been reported to

result in the loss of sexual desire and/or in erectile problems. However, the

frequency with which sexual side effects

occur varies considerably, and the drugs that have a very high incidence of

decreased libido have been marked with*.

**Long-acting calcium channel blockers are

more likely to decrease desire and impair erection than the short-acting

preparations.

(Modified from Kaplan HS: The sexual

desire disorders, New York, 1995, Brunner/Mazel, p. 287. Reprinted with

permission.)

|

Psychosocial Issues and HSD

Psychosocial causes of low sexual

desire include the following6 (pp.

119-129):

1. Religious orthodoxy (a factor

that is “oversimplified at best”)

2. Anhedonic or

obsessive-compulsive personality style (accompanied by usual

difficulties of displaying

emotion and discomfort with close body contact)

3. Primary sexual interest in

other people of the same sex

4. Specific sexual phobias or

aversions (after sexual assault as an adult or child28)

5. Masked paraphilia (perversion)

6. Fear of pregnancy

7. “Widower’s syndrome” (sexual function

difficulties, usually in the areas of desire

or erection, in a man after his

wife has died, resulting from attachment to his

wife or the unfamiliarity of

sexual activity with a new partner)

8. Relationship discord (cause,

effect, or coexistence with HSD may be difficult

to determine)

9. Lack of attraction to a

partner

10. Poor sexual skills in the

partner (“lousy lover”)

11. Fear of closeness and

inability to fuse feelings of love and sexual desire (especially

in men [see “Acquired and

Situational Absence of Sexual Desire”

above])

Relationship Discord and HSD

On the basis of clinical

impression, relationship discord and HSD seem to be frequently

related to each other. When two

sexual partners who love each other and

have no sexual concerns

are engaged in a dispute, it is commonplace to declare a

sexual moratorium until the

conflict resolves. It is as if one says to

the other, ‘I’m angry at you and

don’t feel like going to bed with

you while I have these feelings’.

It is logical to theorize that some

instances of acquired HSD that

are nonspecific in origin may represent

submerged anger about which the

person is unaware. Experimental

evidence exists for the idea of

suppressed sexual desire in the

presence of anger.29

Such theorizing may provide direction for clinical

care. This observation about

anger may, in some instances, relate

to the finding that when woman

with and without HSD were compared, the former

“reported significantly greater

dissatisfaction with nearly every reported relationship

issue.”30

In the concluding chapter to

their multi-authored book on the subject of Sexual

Desire Disorders, Leiblum and

Rosen summarized the views of contributors generally,

saying that “ . . . relationship

conflicts are viewed by the majority of our contributors

as the single most common cause

of desire difficulties”31 (p. 452).

From personal clinical

experience, they found that women

partners “were more aware of and less willing

to tolerate relationship

distress, and consequently that desire in women is more readily

disrupted by relationship

factors” (p. 449). At the same time, humility was suggested

with treatment because

all-too-often less marital discord resulted without any accompanying

change in sexual desire (p. 451).

It is logical to theorize that some

instances of acquired HSD that are

nonspecific

in origin may represent submerged

anger about which the person is

unaware.

|

Madonna/Prostitute Syndrome and HSD

Freud described a man choosing

one woman for love and another for sexual activity

and seemingly unable to fuse the

two.2 He referred to this idea as the Madonna/

Prostitute syndrome. It seems

especially applicable today to many young men who

relate experiences consistent

with an acquired and situational form of HSD.

Multiple Etiological Factors in HSD

Sometimes HSD seems to result

from the operation of only one of the factors described

above: a hormone deficiency or

the onset of a debilitating illness. More often than not,

the onset (especially of the

acquired form) can probably best be explained by multiple

factors.32

A couple in their late 20s explained that

during the two years before their marriage

and the three years before she became

pregnant their sexual experiences were

mutually initiated, frequent, pleasurable,

and free of problems. After the delivery of

her child, attempts at intercourse were

painful for her. Her husband knew of this

but persisted in approaching her sexually.

After telling him of her discomfort on

one occasion, she felt she had little

alternative but to “put up with it,” until finally

she became quite disinterested and “shut

down.”

Both partners described her as a person who

could not candidly and frankly talk

about her feelings, especially when she was

angry. Being forthright was discouraged

in her family-of-origin, particularly by

her alcoholic father who was verbally

abusive to her when she said something he

found unpleasant. It seemed that the

current sexual difficulties were

superimposed on some issues concerning her personality

and problems in their relationship as a

couple. The treatment program

centered on her expressiveness, as well as

“communication” and sexual issues. Her

ability to talk openly about her feelings

improved dramatically. Her husband was

upset with himself as he discovered the

extent of her vaginal and psychological

discomfort and his own insensitivity. As

their sexual experiences resumed, she discovered

that her dyspareunia disappeared. However,

although lovemaking was

more frequent than before, her previous

sexual urge did not return.

Investigation of Hypoact

ive Sexual Desire Disorder

Given the etiological

heterogeneity and therapeutic complexity of

HSD, careful investigation of the

complaint and establishing the correct

subcategory is often the most

important contribution that can be

made by a primary care physician.

Scrutinizing the history of the

patient and couple is usually the most

revealing part of the

examination. Concerns about sexual desire usually

surface in the context of a

couple’s relationship. The patient often

appears unruffled, and the

partner seems the one who is more distressed.

The patient becomes upset

secondarily if the partner is implicitly or

explicitly threatening to

dissolve the relationship. Sexually interested

Given the etiological heterogeneity and

therapeutic complexity of HSD, careful

investigation of the complaint

and

establishing the correct

subcategory is

often the most important

contribution

that can be made by a primary

care clinician.

|

women who are partners of

disinterested men may also describe doubts about themselves

and wonder if they are the source

of the difficulty, thinking (for example) that

they are sexually unappealing.

The disinterested person often does not express worry

about himself or herself but more

about the unfulfilled sexual needs of the partner.

Occasionally, the disinterested

partner seeks help. The reason is often a feeling of

sexual abnormality because such

patients compare themselves, for example, to (1) how

they felt in the past, (2)

friends and partners, and (3) depictions of “sex” on TV and the

movies.

Complaints about sexual desire

are infrequent in patients without partners. One

exception is when a person

believes that their lack of sexual interest contributed to a

disrupted previous relationship

and is apprehensive about it happening again.

History

Comprehensive assessment of a

complaint about sexual desire involves asking an initial

open-ended question, followed by

specific inquiry concerning at least three areas:

• Sexual behavior

• Psychological manifestations of

sexual stimuli

• Body changes in response to

sexually arousing stimuli

Specific issues to inquire about,

and suggested questions include the following:

1. Duration (see Chapter 4,

“lifelong versus acquired”)

Suggested Question: “Has a

feling of low sexual desire always

ben part of your life or was

there a time when this was not

a problem?”

2. Sexual behavior with the usual

partner (see Chapter 4, “generalized versus

situational”)

Suggested Question when Talking

with a Heterosexual Man/Woman: “About how

often are you and she/he sexualy

involved with each

other?”

Additional Suggested Question

when Talking with a Heterosexual Man/Woman:

“What kind of thoughts do you

have before or during your

sexual experiences?”

3. Sexual behavior with other

partners of the opposite sex (see Chapter 4, “generalized

versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “Have you

had sexual experiences with other

women/men since you’ve ben in

this relationship ?”

4. Sexual behavior with other

partners of the same sex (see Chapter 4, “'Generalized

versus situational”)

Part II

Sexual Dysfunctions in Primary Care: Diagnosis, Treatment, and

Referral 178

Suggested Question: “Are you

sometimes sexualy aroused by

thoughts of other men/women?

Additional Suggested Question if

the Answer is, “yes”: “Apart from thoughts,

have you had sexual experiences

with other men/women?”

5. Sexual behavior through

masturbatory sexual activity (see Chapter 4, “generalized

vs. situational”)

Suggested Question: “How

frequently do you stimulate yourself

or masturbate ?”

6. Psychological

manifestations—fantasy (see Chapter 4, “generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “How often

do you have sexual daydreams

(or fantasies )?”

Additional Suggested Question: “What

do you fantasi ze about when

masturbating ?” ALSO:

“What do you fantasi ze about when

you’re in the midst of a sexual

experience with another

person

?”

7. Psychological

manifestations—response to pictures with a sexual theme (see

Chapter 4, “generalized versus

situational”)

Suggested Question: “What do

you think about and fel sexualy

when you se a picture or movie

that has a sexual theme?

8. Psychological

manifestations—response to stories in literature (see Chapter 4,

“generalized versus situational”)

Suggested Question: “What do

you think about and fel sexualy

when you read story in which

something sexual ocurs?”

9. Body change—genital swelling

[erection or vaginal lubrication] (see Chapter 4,

“description”)

Suggested Question when Talking

with a Man/Woman: “When you think about

something sexual, what hapens to

your penis/vagina ?”

Additional Suggested Question: “Does

it become hard/do you become

wet?”

10. Psychological accompaniment

(see Chapter 4, “patient and partner’s reaction to

problem”)

Suggested Question: “When you

are sexualy uninterested, what

thoughts are going through your

mind?”

Addition Question: “How does

your wife (husband, partner )

react?”

Patients who regard answers to

questions about sexual desire as private should not

be expected to discuss these

aspects of the topic (at least initially) in the presence of

their partner (see Chapter 6).

When a couple is interviewed together and someone is

asked a question about something

generally regarded as private, the fact of not answering

the question might, itself, be

revealing (i.e., if one partner does not want to answer

a question about masturbation,

the non-answer might convey to the other partner that

there is secret information).

Under such circumstances, it is best to avoid the question

altogether. The clinician must be

careful not to unwittingly coerce someone to disclose

private information to a partner.

Information that was obtained when someone was

seen alone may emerge at a later

time when a couple is seen together but this should

occur only if the patient who previously

asked for privacy takes the initiative.

Questions about thoughts and

sexual fantasies (with masturbation or with a partner)

are often regarded by patients as

even more private than actual behavior. As a result,

there may be obvious reticence to

talk about what occurs in one’s mind. Information

about thoughts and sexual

fantasies can be enormously revealing from a diagnostic

point of view, since it may, for

example, indicate a complete absence of sexual thought,

a sexual desire for someone else,

or, a different sexual orientation than what the person’s

behavior may have suggested.

Physical Examination

The potential significance of the

physical examination in HSD is signaled by the

patient’s history. Considering

the four subcategories described above,

the acquired and generalized loss

of sexual desire is the principal form

in which a diagnostic physical

examination is required. The major

contrasting element separating

the acquired/generalized pattern from

the others is widespread change.

Ordinarily one would not expect to

find physical abnormalities with

the other three forms because of the

absence of such change:

discrepancy in sexual desire, as well as situational

and lifelong/generalized

disorders. With a desire discrepancy, interest continues

to exist by both partners in the

present as it was in the past, but it is nevertheless

problematic because the two

people function at different levels. Where sexual desire

is situationally absent, interest

continues as before except for one particular situation.

In the lifelong/generalized form,

if a physical abnormality existed it would also have

been lifelong, a circumstance

that is possible (e.g., a congenital disorder) but at the

same time usually obvious.

If a physical examination is part

of the evaluation of acquired and generalized loss

of sexual desire, what does one

look for? Before attempting to answer this question,

one must ask what loss of sexual

desire represents. Is it, in fact, a disorder? Or is it a

syndrome (a collection of

symptoms resulting from several causes)? In most instances,

the answer seems to be the

latter. In that sense, loss of sexual desire resembles other

phenomena such as loss of

appetite for food, or fatigue (both are accompaniments of

many different medical and

psychiatric disorders from cancer to depression and neither

are associated with any specific

physical findings on examination).

The acquired and generalized loss of

sexual desire is the principal form in

which a diagnostic physical examination

is required.

|

When the complaint is loss of

sexual desire and the history does not suggest a specific

cause, one looks for evidence of

generalized and previously unrecognized disease

(e.g., renal or cardiac disease)

in a physical examination. One would search also for the

physical changes associated with

abnormalities in endocrine function. The main endocrine

disorders would be hypoandrogen

states and hypothyroidism. Physical signs of

low testosterone in men are often

delayed; in women, they are often absent. Signs of

hypothyroidism may be subtle.

Since generalized disease and endocrine disorders can

coexist, the presence of the

former does not necessarily mean that the explanation for

sexual desire loss has been found

and that a search for an accompanying endocrine

disorder is, therefore,

unnecessary.

Laboratory Studies

Since HSD is occasionally a

result of a hormonal deficiency, laboratory studies usually

become part of the evaluation

process. In men, this should always involve a determination

of the patient’s serum

testosterone and prolactin levels. Segraves17 (p.

285) justifies

this policy in the following

ways:

• Low cost

• Possibility of overlooking

treatable cause of a low desire complaint

• Difficulty in distinguishing

psychological from endocrinological causation

on the basis of history alone

• Negligible risk (i.e.,

venipuncture)

He further emphasizes the

importance of too quickly attributing the cause of low

desire to interpersonal discord,

since low sexual desire may, itself, result in relationship

conflict. In an effort to

determine the cause of a low testosterone level and because of

the negative feedback loop in

relation to the pituitary gland, a follow-up test should

be performed to determine the

patient’s Luteinizing Hormone (LH) status. Other clinicians

propose a somewhat different

format. Kaplan suggests that LH testing should

coincide with testing for

testosterone, free testosterone, prolactin, total estrogens, and

thyroid status (for men)33

(p. 289). Kaplan, and Rosen & Leiblum, suggest that Follicle

Stimulating Hormone (FSH) be

measured as well.32,33

On the subject of laboratory

investigation of sexual desire complaints in women,

Segraves suggested that “ . . .

extensive endocrinological assessment of every case

of inhibited sexual desire in

females is not indicated”17 (pp.

298-99). He adds that,

since many gynecological

conditions may interfere with sexual desire in nonspecific

ways (e.g., causing dyspareunia),

correction of the condition may be sufficient to

reverse the sexual problem. As

well, low sexual desire might occur in postmenopausal

women as a result of

uncomfortable or painful intercourse associated with the

diminished vaginal lubrication.

This symptom commonly accompanies atrophic vaginitis

and is caused by lack of estrogen

stimulation to a woman’s vagina (see Chapter

13). The unusual patient with the

complaint of diminished sexual desire but who

also describes absent menstrual

periods and galactorrhea should have a serum prolactin

determination test performed.

Kaplan differed from Segraves in suggesting

that the hormone profile

described in the previous paragraph be used in women as

well as men; the one exception

being that estradiol be determined instead of total

estrogens33 (p.

289).

Unrecognized, untreated, or

uncontrolled medical and psychiatric disorders may

become evident during the

investigation of a sexual problem. Common sense dictates

that, ordinarily, attention to

the sexual problems be delayed until these other disorders

are under control. Examples

include the following6:

• Depression

• Alcohol or drug dependence

• Spouse abuse

• Active extramarital

relationships

• Severe marital distress with

imminent separation or divorce

Treatment of Hypoactive

Sexual Desire Disorder

In many circumstances, the most

important role of the primary care health professional

is to carefully delineate the

subcategory of desire difficulty and the possible

etiology. While

carrying out this task, patients with HSD, regardless

of cause, will usually appreciate

the primary care clinician’s initial

step of encouraging them to agree

to temporarily stop struggling

with attempts at sexual

experiences (no matter how favorable the circumstances)

and to simply enjoy being affectionate

with their partner.

The history of the couple often

reveals that affectionate exchanges were common

in the past but abandoned with

the onset of the desire difficulties, since affection

was interpreted as a prelude to

an unwanted (and often refused) sexual encounter.

Affection without the “threat” of

any sexual consequence is usually a relief and

something that is highly desired

by the disinterested partner. This arrangement is

easily accomplished in primary

care, and the agreement is best made with both

partners together so that there

is no misinterpretation of directions or mutual

blame.

Specific Treatment Approaches

Specific treatment of a sexual

desire disorder will result from the discovery of a

specific cause. Limits to the

involvement of a particular health professional depends

on that person’s skills and

pattern of practice. An illustration of a specific cause is

that of testosterone deficiency.

For example, Sherwin showed that testosterone is

beneficial in the loss of sexual

desire associated with surgically induced menopause

as a result of bilateral

oophorectomy.19 Also, testosterone may be helpful in

medically

induced menopause that results

from the use of some cytotoxic agents and

radiation in treatment of various

cancers.34-36 A second and more complex example

of a specific etiology is the

discovery and treatment of prostate cancer. In this

instance, sexual counseling has a

major role in program of care and would likely

focus on “here-and-now” issues.

The treatment program may involve the coordinated

work of a nonpsychiatric

physician and sex-specialist or mental health professional

with interest and skills in the

area of sexual rehabilitation. A third and potentially

even more intricate example of a

specific cause is loss of sexual desire after

Patients with HSD usually appreciate the

primary care clinician’s initial step of

encouraging them to temporarily stop

struggling with attempts at sexual

experiences

and to simply enjoy being affectionate

with their partner.

|

sexual trauma. Counseling is

pivotal in treatment and might well extend to past

issues in the patient’s life. The

ongoing care of such a patient would optimally be

undertaken by a health care

professional with psychotherapy skills and comfort in

talking about sexual issues.

Nonspecific Treatment Approaches

Nonspecific methods for the

treatment of a sexual desire disorder must be used if, as is

often the case, specific

explanatory factors cannot be pinpointed. Some clinicians and

patients find that self-help

books are useful in the initial care of a patient with nonspecific

HSD.37 Unfortunately,

few such books exist.

The subcategory of HSD should be

considered in nonspecific treatment objectives

and methods.

Sexual Desire Discrepancy

Differences in sexual desire

among sexual partners are so common as to possibly be

universal. Considered from that

perspective, one might then consider such differences

to be “normal” rather than

“pathological.” The epidemiology of discrepancies in sexual

desire should be conveyed to

patients—not to delegitimize their complaint but to help

them understand that other

nonsexual issues may be significant contributors to the

problem.

Primary care health professionals

can assist partners in the following ways:

1. Understanding the role of

extraneous influences on their sexual experiences

(e.g., fatigue and preoccupation,

especially in relation to the parenting of young

children)

2. Talking candidly about the

sexual expectations that each may have of the other

3. Appreciating the significance

of “transition activities” (see following paragraph)

4. “Negotiating” a sexual

activity compromise

Even before attempting to alter

facets of sexual desire, attention should be paid to the

role of “transition activities”

(e.g., sporting activities or dinners alone). “It is no secret

that modern living produces

tremendous tension which often inhibits sexual interest,

excitement, and performance . . .

The type of transitions employed are of little

moment, the important thing being

that they help move [the patient] from a tense,

pressured state to one which

feels more comfortable and in which he or she is more

open to sexual stimuli . . . When

[transition activities] are done together [with a

partner], they can function as a

bridge into a shared building of arousal and enjoyable

sexual activity”5

(p. 95).

Viewing sexual desire