CHAPTER 3

Screening For Sexual Problems

The most basic, and also most

difficult, aspect of studying sexuality is defining the subject matter.

What is to be included? How much

of the body is relevant? How much of the life span? Is sexuality

an individual dimension or a

dimension of a relationship? Which behaviors, thoughts, or feelings

qualify as sexual—an unreturned

glance? Any hug? Daydreams about celebrities? Fearful memories of

abuse? When can we use similar

language for animals and people, if at all?

Tiefer,

19951

Defining

the subject matter of “sex” is, indeed, difficult but nevertheless crucial,

since

its meaning will determine which

difficulties one is searching for in the process

of screening. The definition and

the screening mechanism must be broad enough to

encompass problems with sexual function

and sexual practices. Problems with sexual

function are reported by patients

rather than observed by health professionals. In

contrast, some sexual practices

may be seen only as problematic by health professionals.

In both instances, the onus

remains on the health professional to elicit the

information.

Problems with sexual function

have been classified in DSM-IV2—a system

heavily

influenced by the research of

Masters and Johnson3 and Kaplan’s revisions.4

On the

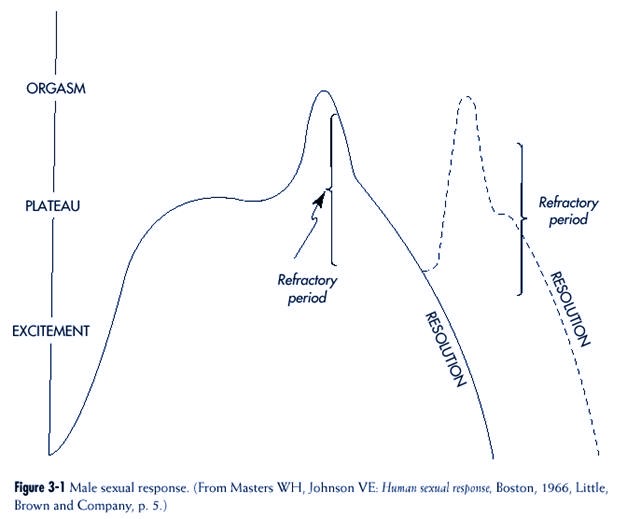

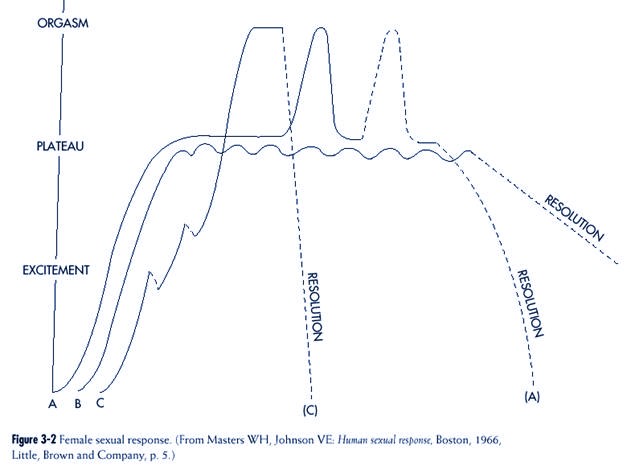

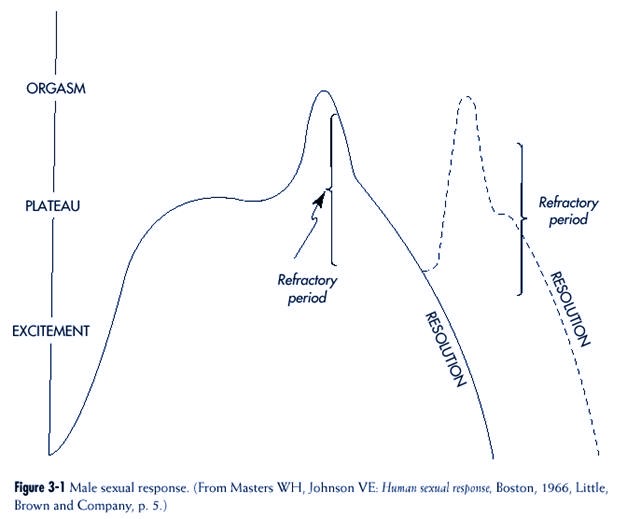

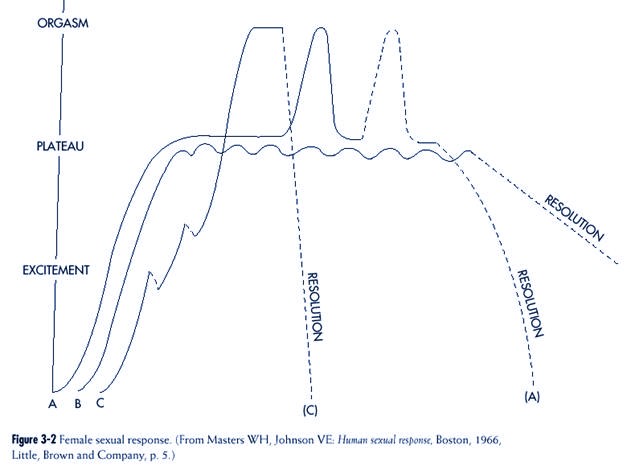

basis of direct observation of

physiological changes associated with sexual arousal,

Masters and Johnson described a “sex

response cycle” that included four phases3 (pp.

3-8)

(Figures 3-1 and 3-2):

• Excitement

• Plateau

• Orgasm

• Resolution

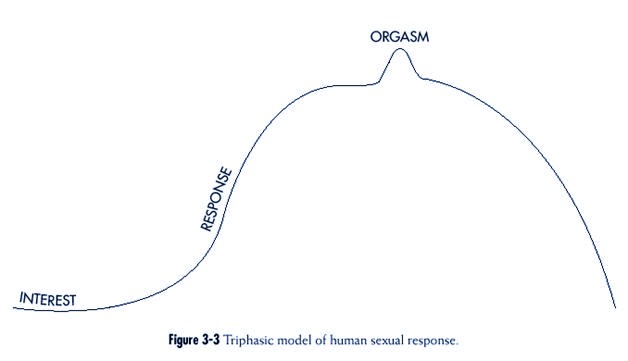

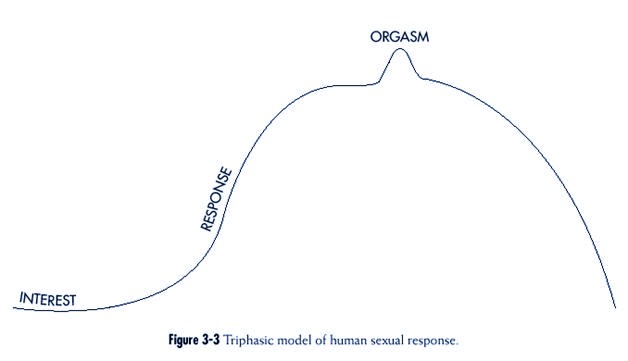

Kaplan added a prior “interest”

or motivational phase to Masters and Johnson’s system4

(pp. 3-7). In so doing, she

reconceptualized the sex response cycle from four parts into

three, which she renamed:

• Interest

• Response

• Orgasm

Kaplan referred to her revision

as a “triphasic model” (Figure 3-3).

Screening Content: Dysfunctions Versus Difficulties

While ideas based on the sex

response cycle are widely used, they have not been universally

accepted. One criticism is that

when considering sexual function, the cycle

seems to progress from one step

to another but that this is not how sexual response is

always ordered. For example,

clinicians will sometimes encounter the occurrence of

orgasm in a woman who does not

feel any preexisting sexual desire. The reality of this

particular observation of the disconnection

between desire and orgasm has been established

in a research context.5

A second critique relates to

gender and the different meanings of “sex” to men and

women. In an exquisitely detailed

and incisive analysis, Tiefer examined the entire

concept of the sexual response

cycle and the extent to which women have been absent

in the formulation of sexual

disorders in the various versions of the DSM1 (pp.

41-58, 97-102). She faults the

DSM classification system for the following:

1. Excessive “physiologizing”

2. Viewing sexual expression as

consisting of reactions of body parts

3. Being “genitally focused”

4. Thinking of “heterosexual

intercourse as the normative sexual activity, repeatedly

defining dysfunctions as failures

in coitus”

From Tiefer’s perspective, the

sexual concerns of women are different and have

been sufficiently outlined in

popular surveys, questionnaire studies, political writings,

and fiction to include such

issues as: intimacy, communication, emotion,

commitment, pregnancy, conception,

and getting old. “. . . women rate affection

and emotional communication as

more important than orgasm in a sexual relationship.

. . “1 (p.

56).

One well-executed, frequently

quoted, and revealing questionnaire study referred

to by Tiefer and which serves to

buttress her argument was conducted by Frank and

her colleagues.6

One hundred predominantly white, well-educated, and “happily

married”

volunteer couples were questioned

concerning the frequency of sexual problems.

The authors found that in addition

to the fact that 40% of the men and 63%

of the women reported sexual

dysfunctions, 50% of the men and 77% of the women

reported “difficulty that was

not dysfunctional in nature.” The “difficulties” are outlined in

Box 3-1. Most importantly from the

point of view of screening, the number of difficulties

reported was more strongly and

consistently related to overall sexual dissatisfaction than the number

of “dysfunctions.”

If one therefore accepts the argument and evidence presented by

Tiefer, a useful screening system

must consider sexual problems to be impairments in

physiology (sexual dysfunctions) and

impairments in the “human relations” part of

“sexual experiences” (i.e.,

difficulties or consequences of the ways people conduct

themselves sexually).

Epidemiology of Sexual

Problems in Primary Care

Apart from what one looks for in

screening (sexual “dysfunctions” and/or “difficulties”)

a major rationale for the inquiry

process is how common the detected phenomena are

in general (epidemiological information

about specific dysfunctions are included in

Part II). The extent of sexual

problems found in medical practices has been studied on

several occasions.

One widely quoted study of sexual

issues in general medicine practice was described

in detail in Chapter 1.7

Another study used a questionnaire (whose validity and reliability

was previously tested) that

contained items concerning dysfunctions and difficulties.

8 Of the 152 patients who

were asked to complete the questionnaire, almost all

did so (93%). The majority of

patients (56%) identified at least one sexual problem on

the questionnaire, and this

compared to 22% having a marital or sexual problem found

by simply examining the patient’s

medical record. Multiple reasons were cited for the

discrepancy, including:

1. The physician did not ask

relevant questions

2. The patient did not

spontaneously report problems

3. The physician did not record

the information in the patient’s

chart

Although identification of a

problem by 56% of patients may appear to

be an overwhelming number to a

clinician, one must remember that

not all people with sexual

problems want treatment.9

Box 3-1

Sexual “Difficulties”

• Partner chooses inconvenient time

• Inability to relax

• Attraction(s) to persons other than mate

• Disinterest

• Attraction(s) to persons of the same sex

• Different sexual practices or habits

• ”Turned off”

• Too little foreplay before intercourse

• Too little “tenderness” after intercourse

Adapted from Frank E et al: Frequency of

sexual dysfunction in “normal” couples,

N Engl J Med 299:111–115, 1998.

Although identification of a problem by

56% of patients may appear to be an

overwhelming number to a clinician,

one must remember that not all people

with sexual problems want treatment.9

|

Screening Criteria

Given the immense numbers of

patients with sexual problems, the need becomes obvious

for a triage system whereby the

nature of a problem and its impact can be evaluated

and proper action taken: (1)

further assessment and treatment or (2) referral. The

beginning of this process

requires a reasonable, respectful, and regular practice by

which the presence of sexual

problems can be identified with just a few questions. For

reasons discussed in Chapter 1,

it is a “given” that patients be provided the opportunity

to discuss a sexual issue if they

desire. To accomplish this goal, some sort of sexscreening

question must be included in an

assessment.

Other than considering specific

sexual practice issues involved in STD and HIV/

AIDS transmission, the idea of

including general sex-screening in a health assessment

has been considered only briefly

by a few authors. Concepts vary from an elaborate

“screening history” requiring 30

minutes10 to a small number of specific screening

questions.11The

rationale for choosing particular questions was not always clear.

Useful screening questions in any

area should observe at least four rules:

1. Screening questions should

encompass a wide spectrum of common problems

A variety of sexual problems may

exist in any community, ranging from frequent

(concerns about genital function,

sexual practices, or emotional communication) to

unusual (confusion about one’s

status as a man or woman). A screening system must be

sufficiently sensitive to at

least “pick up” problems that are common. Freund’s opinion is

that “a problem must be

sufficiently common to justify investigation of an entire population

of patients.”12

Sexual dysfunctions and difficulties, as well as problems related

to

STDs and child sexual abuse, are

far more numerous than other sexual disorders and

these must be uncovered in any

practical sex-screening process13 (pp.43-55).

2. To be practical, screening

questions should be few in number

A small number of questions

recognizes the limited amount of time

that health professionals

(especially nonpsychiatric physicians) spend

with patients and the reticence

that many patients have in spontaneously

talking about sexual issues.

Realistically and reasonably, only a

small amount of health

professional time will be used to ask questions

about sexual matters when the

patient’s major concern is elsewhere.

Suggesting more than a few

screening questions dooms the entire process

from the start.

3. The problem must be of

sufficient severity to justify the effort of asking questions of

the population12

The consequences of sexual

problems must be considered from individual and social

perspectives. In some instances,

the severity of the impact on an individual is easy to

discern (e.g., STDs) but in

others the effect may be more subtle (e.g., repercussions on

a relationship of a coexistent

sexual dysfunction). Without “quality of life” information

in the area of sexual problems,

it becomes difficult to provide clear evidence about the

effect of some problems on the

individual. The existing literature on the effects of

Realistically and reasonably, only a

small amount of health professional

time will be used to ask questions about

sexual matters when the patient’s major

concern is elsewhere. Suggesting more

than a few screening questions dooms

the entire process from the start.

|

sexual dysfunctions on

individuals and relationships, as well as clinical impression, suggest

substantial repercussions13

(pp. 52-55). The outcome of some sexual experiences

such as child sexual abuse are

well documented.14 Newspapers have well

reported the

social disruption caused by STDs

and HIV/AIDS, pedophilia, and child sexual abuse.

4. There must be effective

treatment for problems that are common

The treatments of sexual

dysfunctions and their usefulness are reviewed in Part II.

These four screening criteria can

be applied, for example, to one of the screening

systems commonly used in medical

practice. Part of any medical evaluation includes

asking a series of questions

about the function of different parts of the body. This brief

health questionnaire has been

variously called the “Review of Systems” (ROS) or “Functional

Inquiry” and includes a few

questions about each body system. It is meant to

accomplish two objectives, as

follows:

• To provide more information

about concerns not obviously connected

to the patient’s main complaint

• To uncover undiscussed problems

that the patient may have thought to

be irrelevant or unimportant

Until recently, questions about

sexual issues were not usually part of a medical

screening process. Questions

relating to this subject were not asked or were buried in

questions about other body

systems. For example, questions about sexual function

were included with questions

about a man’s urinary function.

There is no universally

applicable sex-screening formula. Several

approaches can be used,

depending, for example, on such factors as the

comfort and skill of the

interviewer or the age of the patient. Screening

questions asked of adolescents

might well differ from questions asked

of elders.

With the understanding that variety

and flexibility in sex screening are

desirable, one general method is

described below. This approach can

be incorporated easily into the

assessment of any patient whose main concern is not

primarily sexual, specifically,

into the medical “review of systems.” (The ROS concentrates

on body function or dysfunction;

therefore sexual practice issues can be included

easily.) When judging the

usefulness of the proposed sex-screening process, one should

recall the four criteria

mentioned previously, that is, questions should:

• Cover a wide spectrum of common

problems

• Be few in number

• Justify the severity criterion

• Be concerned with problems that

have effective treatments

Questions should include an

additional criterion as well, namely, practicality.

When health professionals choose

sex-screening approaches, the selection is not

usually between systems that are

brief or lengthy. The choice is usually between (1) a

system that is brief and comfortable

to the clinician and inoffensive to the patient or

(2) a complete absence of

any sex-related screening questions whatsoever.

There is no universally applicable

sexscreening

formula. Several approaches can be used.

|

The older style sex-screening

approach used to be: “How’s your sex life?” While this

fulfilled the wide spectrum and

brevity criteria, it was also nebulous and indefinite.

Being so general, it usually

elicited an equally vague answer (“fine”), which was undoubtedly

inaccurate on many occasions. In

addition, the question potentially covered the

whole of a patient’s current

sexual experience rather than concentrating

on what was problematic and

required attention.

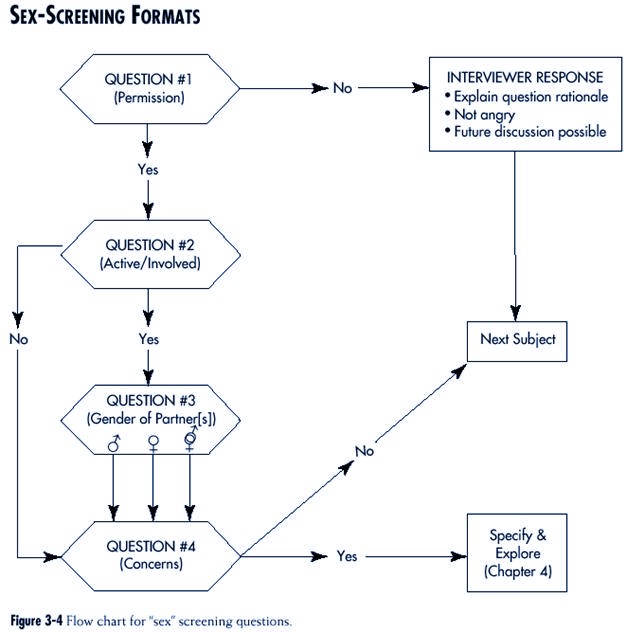

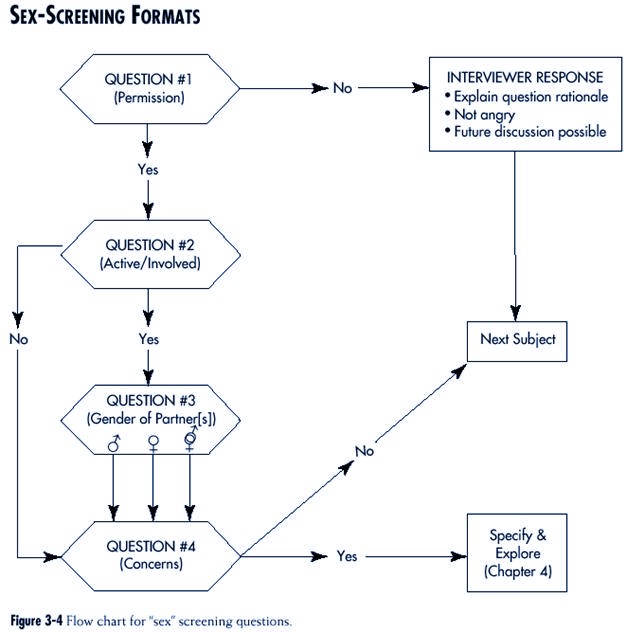

A preferred approach (Figure

3-4 and Box 3-2) begins with the question:

“CAN I ASK YOU A FEW QUESTIONS

ABOUT SEXUAL MATTERS?”

This is not really a “sex”

question but rather preliminary to other questions that

might follow. Use of the

permission technique was discussed in Chapter 2.

The answer to a permission question

is usually “yes.” After consent

is given, the interviewer

naturally continues to the next question. However,

in the unusual situation that the

patient says “no,” the interviewer

The answer to a permission question is

usually “yes.” After consent is given, the

interviewer naturally continues to the

next question. However, in the unusual

situation that the patients says “no,” the

interviewer has no ethical alternative

but to respect the patient’s decision and

continue to the next subject.

|

has no ethical alternative but to

respect the patient’s decision and continue to the next

subject. Before proceeding, some

of the implicit issues mentioned above should be

made explicit. In particular, the

interviewer should explain the rationale for asking the

question in the first place.

Reasons given may include the following:

• That this area is legitimate

for discussion in a medical setting even if

unconventional from the patient’s

point of view

• That the interviewer’s response

is one of understanding rather than

anger

• That the patient is free to

raise the topic at any time in the future

The second screening question

asks the patient: “ARE YOU SEXUALLY ACTIVE?”

This question is common

especially in relation to HIV/AIDS prevention. The question

could be made sharper if a time

frame is added. For example, it might be phrased:

“HAVE YOU BEEN SEXUALLY ACTIVE IN

THE LAST SIX MONTHS?” This

revision might be useful

particularly in situations where sexual activity may be regular

but not necessarily frequent, as for

example, in the elderly.

The meaning of the phrase

“sexually active” could be more specific if it included

some definition of the word

“active.” “Active” might refer to actions with a partner,

with oneself (masturbation), or

both. If a patient has a partner, couple sexual activities

should be the focus of this

question, so that the question might be: “HAVE YOU

BEEN SEXUALLY ACTIVE WITH A

PARTNER IN THE PAST SIX MONTHS?”

If the patient does not have a

sexual partner, the definition of “active” might logically

include solo sexual experiences.

However, since the subject of masturbation is often a

sensitive one for patients and

clinicians and, since it is infrequently reported as a problem

with sexual function or practice,

one might reasonably refrain from asking about

this specific subject in the

context of screening questions.

There are two potential problems

with the word “active”:

• Teenagers may not understand

what the word encompasses. Talking

with teenagers may be one

instance in which the word “sex” is useful,

since teens (unlike adults) often

have a broader definition than simply

intercourse. In using this

approach, the health professional must clarify

what practices are entailed

within the word “sex.”

• Some people interpret the word

“active” concretely and consider themselves

“passive,” so that even if

sexually involved with another person

they might answer the question in

the negative. It might be better to

Box 3-2

Sex Screening Questions

1. Can I ask you a few questions about

sexual matters?

2. Have you been sexually active with a

partner in the past six months?

3. With women? men? both?

4. Do you or your partner have any sexual

concerns?

|

use the word “involved” instead

of “active” in such situations. (A strong

counter argument is that the word

“active” has become part of the English

lexicon and that professionals

and adult patients are adjusted to

its use.)

The final version of the second

sex-screening question might therefore be: “HAVE

YOU BEEN SEXUALLY ACTIVE (OR

INVOLVED) WITH A PARTNER IN THE

PAST SIX MONTHS?”

A “yes” answer to the question of

sexual activity results naturally in the interviewer

proceeding to the next item,

which may be about the gender of the partner—opposite

or same sex. (Questions are

formulated by using the words, “men” and “women,” rather

than “opposite” and “same”[see

immediately below].) Acquiring information about sexual

orientation is vital for reasons

outlined in Chapter 7 (see “Sexual Orientation: Issues

and Questions”).

The third sex-screening question

is actually an extension of the second and attempts

to determine with whom the

patient has been sexually active. The question is asked

only if the patient says “yes” to

the second question and can be phrased (e.g., when

talking with a man): “HAVE YOU

BEEN SEXUALLY ACTIVE WITH WOMEN,

OTHER MEN, OR WITH BOTH?”

Following a “no” answer to the

question of whether or not a patient is sexually

active, an attempt should be made

to discover whether or not the person’s inactivity

is a concern. If it is, this

requires some exploration by the interviewer and an explanation

from the patient. This, in turn,

leads into a diagnostic process. If sexual

inactivity is not a concern, the

interviewer could naturally proceed to the fourth

and last screening question,

which is: “DO YOU OR YOUR PARTNER HAVE

ANY SEXUAL CONCERNS?”

The utility of a question about

“concerns” lies in the fact that it is open-ended and

problem-oriented. However, one

problem with this question is its subjectivity. A more

direct, objective, and still open-ended

and problem-oriented version would be, “DO

YOU OR YOUR PARTNER HAVE ANY

SEXUAL DIFFICULTIES?” A third possibility

is the same question but with

some added specific examples. The question

could then become: “(for a

man) DO YOU OR YOUR PARTNER HAVE ANY

SEXUAL DIFFICULTIES, SUCH AS WITH

YOUR INTEREST LEVEL, ERECTIONS,

OR EJACULATION?” (For a woman) “.

. . SUCH AS WITH YOUR

INTEREST LEVEL, VAGINAL

LUBRICATION, ORGASMS, OR INTERCOURSE

PAIN?” These

examples are of sexual dysfunctions. A clinician could, if desired, substitute

other examples such as STDs.

Any of these four questions

should fulfill the four criteria for screening questions

described above. If the screening

professional can ask only one question, the fourth is the

most desirable.

Conclusion

A screening system for “sex”

questions is a necessity for health professionals. The

arrangement must be comprehensive

(encompassing problems with sexual function

and sexual practices), the

questions few in number, and the problems sufficiently severe

and treatable. Practicality also

helps. There is not much use in proposing a system that

no one will use.

Screening questions about sexual

issues are a vital part of the health professional’s

intake procedure. However,

screening questions cannot be definitive. The question

inevitably arises: “What do you

do if you get a positive answer?” One does, of course,

the same as one would do with any

other subject. In the practice of a health professional,

this means allowing the patient

to talk and ask more questions as part of a

diagnostic process. This, in

turn, leads to a conclusion and to a treatment plan. The

next chapter discusses the first

of these two steps.

REFERENCES

1. Tiefer L: Sex is not a natural act and

other essays, Boulder, 1995, Westview Press.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of

mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, 1994, American

Psychiatric Association.

3. Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human sexual

inadequacy, Boston, 1970, Little, Brown and

Company.

4. Kaplan HS: Disorders of sexual desire, New

York, 1979, Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

5. Rosen RC, Beck JG: Patterns of sexual

arousal: psychophysiological processes and clinical

applications, New

York, 1988, The Guilford Press, pp 42-43.

6. Frank E, Anderson C, Rubenstein D:

Frequency of sexual dysfunction in normal couples,

N Engl J Med 299:111-115,

1978.

7. Ende JE, Rockwell S, Glasgow M: The sexual

history in general medicine practice, Arch

Intern Med 144:558-561,

1984.

8. Moore JT, Goldstein Y: Sexual problems

among family medicine patients, J Fam Prac

10:243-247,1980.

9. Garde K, Lunde I: Female sexual behaviour.

A study in a random sample of 40-year old

women, Maturitas 2:225-240, 1980.

10. Munjak DJ, Oziel LJ: Sexual medicine

and counseling in office practice: a comprehensive treatment

guide, Boston,

1980, Little, Brown and Company, pp 3-10.

11. Kolodny RC, Masters WH, Johnson VJ: Textbook

of sexual medicine, Boston, 1979, Little,

Brown and Company, pp 587-588.

12. Freund K: Screening in primary care for

women. In Carr PL, Freund KM, Somani S

(editors): The medical care of women, Philadelphia,

1885, W.B. Saunders Company, pp 1-13.

13. Hawton K: Sex therapy: a practical

guide. New York, 1985, Oxford University Press.

14. Browne A, Finkelhor D: Impact of child

sexual abuse: a review of the research, Psychol

Bull 99:66-77, 1986.