CHAPTER 1

Talking About Sexual Issues:

History-Taking and Interviewing

Significant obstacles exist between

the clinician’s capacity to ask a question and the patient’s capacity to

respond. Whereas comprehensive

knowledge is required of the cardiovascular system to cover all the

symptom bases, these questions

are typically asked without anxiety or inhibition once the questions are

memorized and their rationale

understood. Similarly, the patient experiences little or no hesitancy in

responding truthfully to these

paths of inquiry. The same milieu does not generally exist with sexual history

taking.

Green,

19791

Other than

descriptions of interviewing methods used by researchers2

and opinions

of specialist-clinicians who

treat people with sexual difficulties,3 health

professionals

have little guidance on the

subject of talking to patients about sexual issues. Less

still is any direction given to

primary care clinicians for integrating this topic into their

practices. For guidance on

sex-related interviewing specifically, the primary care clinician

may want to begin by examining

clinical research in the general area of interviewing,

as well as the observations of

those who have written about their personal general

interviewing ideas and practices.4

Some Research

on General Aspects of Health-related

Interviewing and History-Taking

As Rutter and Cox stated, “many

practitioners have advocated a variety of approaches

and methods on the basis of their

personal experience and preferences. . . [but]. . .

there has been surprisingly

little systematic study of . . .interviewing techniques for

clinical assessment purposes.”5

Only a few items from the research literature in the area

of health-related interviewing

are described here.

Direct Clinical Feedback

One interviewing-research

question has been the value of direct clinical supervision in

the development of interviewing

skills generally. While this form of supervision makes

sense intuitively, the process

has been subject to little research. One study compared

the value of direct clinical

feedback to medical students using four different techniques:

three of them (audio replay,

video replay, and discussion of rating forms) were

compared to a fourth whereby a

student interviewed a patient and subsequently discussed

findings (indirectly) with a

supervisor.6 The students who received any of the

three direct clinical

feedback methods did much better. The same individuals were

assessed five years later as

physicians and strikingly (since long-term follow-up studies

in health education are quite

unusual) those who received feedback “maintained their

superiority in the skills

associated with accurate diagnosis.”7

In another study, two groups of

medical students were videotaped on three different

occasions during the school year

while performing a history and physical examination.

8 Both groups viewed their

own tapes but one group received additional evaluative

comments by a faculty member. By

the end of the year, those in the latter group performed

significantly better in the

following:

• Their interviewing verbal

performance

• The content of the medical

history they obtained

• Their use of physical

examination skills

Teaching Interviewing Skills

One might conclude from the

findings of both studies that if direct supervision

proved superior in the process of

learning interviewing skills generally, the same conclusion

might be drawn for interviewing a

patient about a specific subject such as

“sex.” The importance of this

conclusion can not be exaggerated when one considers

the dearth of questions about

sexual issues in ordinary health histories. One way to

change this situation is to

deliberately teach the skill of sex history-taking and interviewing

in health professional schools

instead of (as now often seems to be the case)

seemingly expecting clinicians to

absorb this skill in the course of developing their

clinical practices.

It may be instructive to also

consider a series of studies of interviewing styles that

were based on talks with mothers

who were taking their children to a child psychiatry

clinic.5,9-14 These

interviews were conducted by experienced health professionals. Four

experimental interviewing styles

were compared for their efficacy in eliciting factual

information and feelings. The

four were given the following names:

• Sounding board

• Active psychotherapy

• Structured

• Systematic exploratory

The research group concluded that

good-quality factual information required detailed

questioning and probing, that

several approaches were successful in eliciting feelings,

and that these two issues were

compatible in the sense that attending to one

did not detract from the other.

Although their findings were related more to the

process of interviewing and not

specific to any particular topic, their conclusions

seemed as applicable to the area

of “sex” as with any other. The clinically apparent

need for the health professional

to initiate sex-related questions when talking with

patients (see “Interviewer

Initiative” in Chapter 2) echoes the conclusion of these

studies that asking detailed

questions is more productive. In extrapolating from

these studies and insofar as

“sex” can legitimately be seen as psychosomatic, there

should be no incompatibility in

the attention that a clinician might give to the

acquisition of information that

is factual and related to feelings when talking to a

patient about sexual matters.15

Another study that examined the

proficiency in history-taking generally in secondyear

medical students also may have

implications for sex history-taking.16 Two

methods

of measurement were used:

• The Objective Structured

Clinical Examination (OSCE)

• A written test

The authors believed that patient

information could be divided into three domains:

1. Information required to make a

diagnosis

2. Information to determine risk

for future disease

3. Information to assess the

patient’s available support system

The study found that students

concentrated on obtaining diagnostic information on

both of the tests used and that,

unless modeled by faculty, information on risk factors

and psychosocial data was

omitted. Since sex-related problems are often relegated to

the psychosocial arena, an

assumption that one might derive from this study is that

unless a sexual problem is given

by the patient as a chief complaint (and therefore in

the “diagnostic” arena) it is

unlikely to be detected—unless faculty modeling occurs.

Extrapolations from all of these

studies in interviewing and historytaking

as far as “sex” is concerned

imply the following:

1. Teaching of skills by direct

supervision should be included in

health science educational

programs

2. Direct questions are more

productive

3. There is no difficulty in

attending to factual information and

feelings

4. Faculty modeling is a

significant element in the learning process

Integrating Sex-related Questions into a General

Health History

Texts on general aspects of health-related

history-taking and interviewing

reveal great inconsistency in the

definition of a “sexual history” and consequently

in what is expected of the health

professional. Some texts contain little or no information

on the subject17;

others include a separate chapter 1,18-22 or

portion of a chapter.

4,23 Complete

or partial chapters are usually brief and the information is so concentrated

that the content is difficult to

use in a practical sense. Some authors focus on

“sex” as it relates to a particular

psychiatric or medical disorder, for example:

1. Sexual desire in depression24

2. Sexual abuse as it relates to

dissociation, posttraumatic stress disorder, and somatization

disorder25

3. The “hysterical” patient26

4. Sexually transmitted diseases27

Others focus special attention on

a particular sexual problem.21 Some

authors recommend

asking about the patient’s past

sexual development28; others suggest a focus

on

current problems.20

Specific suggested questions are offered by some,19

and others may

Extrapolations from studies in interviewing

and sex history taking imply:

1. Teaching of skills by direct supervision

should be included in health science

educational programs

2. Direct questions are more productive

3. There is no difficulty in attending to

factual information and feelings

4. Faculty modeling is a significant

element

in the learning process

|

also include a brief rationale

for these questions.29 When questions are

suggested, little

guidance is usually given on when

they should be asked.

“Human Sexuality” textbooks are

also of limited help. Some may include a chapter

on “assessment” or “sex”

history-taking and interviewing.30-32 Although

the quality of

information in these chapters may

be high, the amount that is squeezed into this one

section results in “information

overload” and therefore becomes of minimal practical

use to the frontline clinician.

Journal articles on sex

history-taking provide a similar variety of opinions about

what should be included. The

advent of HIV/AIDS has pushed physicians into promoting

the need for taking a sex

history.33,34 So, too, is the effect on health

professionals

of the recognition of the

frequency of child sexual abuse in the history of adults.35

Sometimes, history-taking

suggestions are in the form of topics to be covered rather

than specific questions to be

asked.36

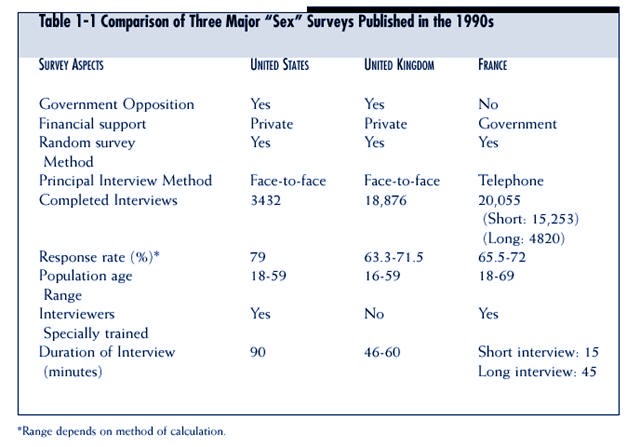

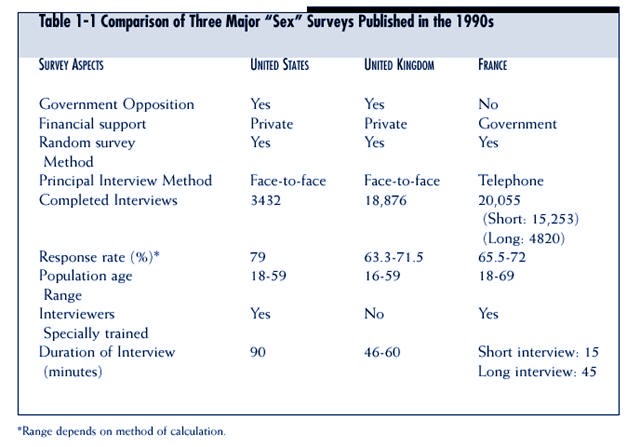

Among the more informative

sources of information on sex-related interviewing

and history-taking (but still of

limited value to primary care clinicians) are the comments

about interviewing that are

attached to some of the community based research

reports on sexual behavior.

Kinsey and his colleagues included a chapter on the subject

of interviewing in their volume Sexual

Behavior in the Human Male.37 More

recently, largescale

“sex” surveys in the United

States38 (see introduction to PART I), the United

Kingdom,39 and

France40 included reports about the interviewing

process when outlining

their study design (see Table 1-1

for a comparison of some aspects of the three

surveys).

Thus health-related interviewing

texts, specialty books on “Human Sexuality,” and

journal articles are enormously

variable in their content when considering sex historytaking

and tend to be disappointing in

that they provide little aid to clinicians.

Studies in Medical

Education That Relate to General Aspects

of Sex History-taking

In the 1960s and 1970s, sex

education in medical schools concentrated on providing

information about “sex” and

helping people to be more at ease with the subject.

Beginning in the 1980s, some

schools added a focus on skills, that is, interviewing

and history-taking, or, to put it

differently, they added focus on the

practical issue of how physicians

and patients actually talk about the subject of

sex. Attitudes and practices of

sex history-taking have been examined from a

research viewpoint, and

understanding conclusions from these studies may provide

some practical direction.

Comfort and Preparedness

Comfort and preparedness in

“taking a sexual history” was studied in a group of

first-year medical students.41,42

The idea of including this topic in a medical history,

as well as facilitating factors

and obstacles, was examined. The authors found

that the sexual orientation of

the patient seemed an important variable in that

students expected to be most

comfortable with heterosexual patients of the same

sex and least comfortable with an

(presumably gay) AIDS patient. The authors

also found that “the most

consistent predictor of both knowledge and attitudes

about sexual history-taking was a

student’s personal sexual experience.” The kinds

of experiences that were

particularly linked with comfort and preparedness in taking

a sexual history were:

1. Having taken a sexual history

in the past

2. Having spoken to a health

professional oneself about a sexual concern

3. Having a homosexual friend

Age seemed related only to the

extent that older students expected to be more comfortable

with an AIDS patient.

Practice

The importance of practice was

seen in a study of medical students who were involved

in different sexuality curricula

at two different schools.43 In one,

students were not

expected to be involved in sex

history-taking. In the other, students conducted a sex

history with a volunteer or

observed one taking place. The curricula were otherwise

similar. The three groups (no

interview, conducting an interview, and observing an

interview) were assessed

regarding knowledge about:

• Sexual issues

• The propriety of including

sex-related information in a medical history

• Self-confidence in the ability

to conduct the interview

The students who previously

conducted a sex-related interview did significantly better

than those who were neither

participants nor observers. However, findings relating to

students who were in the observer

group were intermediate on measures of knowledge

and perceived personal skill.

The reasons, “why other doctors

fail to take adequate sex histories,” were determined

in another study44

and include the following:

1. Embarrassment of the

physicians

2. A belief that the sex history

is not relevant to the patient’s chief

complaint

3. Belief that they (the

subjects) were not adequately trained

A large majority of senior

medical students thought that knowledge by

a physician of a patient’s sexual

practices was an important part of the

medical history but only half

were confident in their ability to actually

acquire this information from a

patient.

Social and Cultural Factors

Social and cultural factors

relating to the patient also seem to influence whether or not

a sex history is taken. Sixty

emergency room medical records of adolescent girls who

complained of abdominal pain that

required hospitalization were reviewed.45 The

authors found that asking about

sexual issues in the context of an emergency room

occurred a great deal more with

individuals from minority groups than with white

adolescents with the same

complaint. They concluded that racial stereotyping was an

important factor in asking

questions about sexual experiences. Although they supported

the inclusion of such questions

in an assessment, the authors argued that histories

in an emergency room should be

characterized by efficiency and a minimum of

irrelevant questioning, and that,

in spite of the pertinence of questions about sexual

experiences to the complaint of

abdominal pain in an adolescent girl, such questions

were more often omitted in those

who were white.

Skills Versus Self-awareness

In a demonstration of the sex

history-taking usefulness of direct teaching of skills compared

to sexual self-awareness, family

practice residents were randomly allocated to

two groups emphasizing one or the

other of these approaches.46 Each

group received

two hours of training. The first

hour was common to both groups and involved general

counseling skills and information

about sexual dysfunctions. In the second hour, the

two groups were separated and

concentrated on sexual history-taking issues or the

comfort and sexual self-awareness

of the resident. One week later, residents conducted

a videotaped interview with a

simulated “patient” with sexual and other problems but

who was also instructed to reveal

sex-related information only if asked directly. Almost

all subjects (11/12) in the

skills-oriented group asked the “patient” about the nature of

her sexual difficulty, compared

to 25% (3/12) of the awareness-oriented group.

Clinical Practice

A large majority of senior medical students

thought that knowledge by a physician

of a patient’s sexual practices was

an important part of the medical history

but only half were confident in their

ability to actually acquire this information

from a patient.

Physicians in clinical practice

(versus medical students and residents in educational

programs) also have been studied.

In a widely quoted and well-conceived study, a

group of primary care internists

were taught to ask a set of specific sex-related questions

of all new patients attending an

out-patient clinic.47 These physicians were then

compared to nontrained

colleagues. After the visit, physicians completed a questionnaire

and patients were interviewed

concerning their encounter with the physician.

The following results were

noteworthy and instructive:

1. More than half of the patients

had one or more sexual problems or areas of

concern

2. Age and sex did not influence

the prevalence of sexual problems

3. Many more patients (82%) who

saw trained physicians were asked about sexual

functioning than those who saw

untrained physicians (32%)

4. Among both groups of

physicians, discussions about sexual issues were more

likely if the patient was less

than 44 years old

5. Ninety one percent of the

entire group of patients thought that a discussion

about sexual issues was, or would

be, appropriate in a medical context and

approval was almost unanimous

(98%) among patients whose physician had, in

fact, included a sex history

6. Age of the patient was not a

factor in the determination of appropriateness

7. Thirty eight percent of the

entire patient group thought that follow-up for sexual

problems would be helpful

8. Physicians found that, in many

instances, the sex history was helpful in ways

other than simply as a means to

identify sexual problems or concerns

In summary, medical students,

family practice residents, and physicians in clinical

practice in the community have all

been studied on the issue of sex history-taking. The

following factors appear to

influence the learning process:

1. Having talked to patients

about sexual issues in the past

2. Having a sexual problem

oneself and having discussed it with a health

professional

3. The sexual orientation of the

patient

4. Having a homosexual friend

5. The belief that asking about

sexual issues is relevant to the patient’s concerns

6. Having received specific

training

7. Social and cultural issues

Studies in Medical

Education on Sex History-taking

in Relation to HIV/AIDS

There is little question that

HIV/AIDS is the major impetus for the recent teaching

of sex history-taking in medical

schools and the promotion of sex history-taking

among practicing physicians. This

development results from the knowledge that sexual

activity represents the prime

method of viral transmission. Many agree with the

statement “that the taking of a

candid and nonjudgmental sexual history is the cornerstone

of HIV preventive education. . .”48

Recognition of the crucial position of

physicians in HIV prevention has

resulted in several studies of physician

sex history-taking practices.

In general, studies of physicians

with different levels of medical

education and experience (e.g.,

internal medicine residents, primary

care clinicians) and using

various research techniques (e.g., standardized

patients, telephone interviews)

indicate the infrequency and/or

inadequacy of history-taking

around vulnerability to HIV/AIDS

infection and the consequent

inability to take preventive measures.

48,49-52 One of

these surveys demonstrated that in spite of the finding that

68% of 768 respondents said they

had received “human sexuality training” in medical

school, only a small minority of

primary care physicians routinely screened

patients for high-risk sexual

behavior.51 “Sexuality Training” was evidently helpful

after the fact,

since physicians who received this training in their medical education

“felt more comfortable in caring

for patients known to be infected. . .” with HIV.

Another study showed that while

self-reports of questions concerning homosexuality

doubled and questions about the

number of sexual partners tripled, questions

concerning sexual practices

increased by only 50% over the five years of

the project (1984-89).53

Yet another study demonstrated that only 35% of primary

care physicians reported that

they routinely (100%) or often (75%) took a

sex history from their patients.

Less than 20% of those who took histories

reported asking questions regarding

sexual activities that increase the risk of

acquiring HIV/AIDS.54

Two particularly revealing

projects involved a visit to primary care clinicians by a

simulated patient. In the first

study, physicians agreed to participate after being told

that a simulated patient would

appear in their practice.55 The

“patient” was female in

order to include

obstetrician-gynecologists. Other than obtaining prior agreement, the

“patient” was unannounced. She

revealed the following information:

• That she had been exposed to Chlamydia

by a previous partner

• She expressed interest in

engaging in sexual activities with a new partner

• She wanted to talk about

concerns regarding STDs generally and HIV

in particular

Comparisons were subsequently

made between the report of the “patient” and the selfreport

of the physician on several

issues, including risk assessment and counseling

recommendations. The greatest

discrepancies (all of which involved physicians overestimating

their history-taking skills in

the opinion of the “patient”) occurred with the

following topics:

• STD history

• Patient use of IV drugs

• Patient sexual orientation

• Condom use

• Counseling concerning anal

intercourse and use of a condom

• Safe alternatives to

intercourse

In spite of the finding that 68% of 768

respondents said they received “human

sexuality training” in medical school,

only a small minority of primary care

physicians routinely screened patients

for high-risk sexual behavior.

|

In the second simulated-patient

study, the “patient” had a history of engaging in

sexual activities that made her

vulnerable to HIV/AIDS infection.56 Physicians

were

provided with educational

materials before the visit. Whether these

materials were used or not did

not alter the finding that the questions

least frequently asked of the

“patient” were about oral or anal sex practices,

sexual orientation, and the use

of condoms. The authors concluded

that there was a need for

prevention training.

From these HIV/AIDS-related

studies, one might conclude that the

generic form of “Human Sexuality”

training in medical schools seems

to result in greater acceptance

toward those who already have HIV/

AIDS but it is insufficient in preventing

transmission. Effective preventive

behavior by physicians evidently

requires more specific curricular intervention

that addresses history-taking

skills and, in particular, inquiry

about patient sexual practices.

What, Then

, Is the Definition of a Sex (or Sexual) History?

Is taking a sex history by a

family physician who has only a few minutes to ask questions

about sexual issues and wants to

concentrate on, for example, STDs and HIV/

AIDS-related sexual behavior the

same as for a forensic psychiatrist who is evaluating

a patient referred because of

pedophilia? Is it the same (in time and content) for a

health professional asking

questions about child sexual abuse as for an interviewer

involved in a population survey

in which each interview might take hours to complete?

Is it the same for a clinical

psychologist or psychiatrist who asks a few screening questions

as part of the assessment of a

patient who is depressed as it is for a clinical sexologist

who is evaluating a couple

referred specifically because of erectile problems?

The answer to these questions is

obviously “no.” In all these situations, the result

might be called a “sex history”

but the time involved and the questions asked would be

quite different. Rather than use

the singular, it might be more reasonable to talk in the

plural, that is, of sex

histories—inquiries that are sexual in nature but differ because of

the diverse requirements of the

situations. In fact, instead of considering

a “sex history” or “sex

histories,” it may be easier to simply think

about the task of talking to a

patient about sexual matters.

A primary care clinician must

therefore be skilled in talking to

patients about a variety of

sexual issues, depending, among other

things, on the patient, the

problem presented, the amount of time

available for questioning, and

the context in which the patient is

seen.

Practical Aspects

of Introducing Sexual Questions

Into a Health-related

History

Practical aspects of talking to

patients about sexual matters can be viewed in the context

of the familiar format of why,

who, where, when, how, and what. This conceptual

The generic form of “Human Sexuality”

training in medical schools seems to

result in greater acceptance toward

those who already have HIV/AIDS but it

is insufficient in preventing transmission.

Effective preventive behavior by physicians

evidently requires more specific

curricular intervention that addresses

history-taking skills and, in particular,

inquiry about patient sexual practices.

Instead of considering a sex history or

sex histories, it may be easier to simply

think about the task of talking to a

patient about sexual matters

|

arrangement has been used

elsewhere in dissecting this subject but the content here is

different.1

So is the order. Issues that involve the manner in which questions

are

phrased (how) are considered in

Chapter 2, and which questions to ask (what) are

discussed in Chapters 3, 4, and

5.

Why

Discussion May Not Occur

(Box 1-1)

The following may be reasons why

discussions of sexual topics in a

health care setting do not occur:

1. Not knowing what to do with

the answers is the most common

reason given by physicians in

particular for avoiding the topic of

“sex” in medical history-taking.

When investigating what this explanation means,

two factors become evident:

• Uncertainty about what the next

question should be

• Perplexity regarding what to

offer the patient after all the questions are

asked and “Pandora’s box” is

opened

2. Worry that patients might be

offended by an inquiry into this area is a recurrent

theme of medical students. In

spite of the almost uninhibited media display of

sexuality, many people (including

medical students and physicians) continue to

regard sexual issues as

“personal” and are concerned that questions in this area

might be regarded as intrusive.

3. Lack of justification is a

common explanation given by medical students for the

frequent omission of sexual

topics from medical histories. However, when some

medical problems are presented to

a physician, specific aspects of a person’s

sexual life experience are often

the subjects of inquiry (e.g., issues that may be

medically relevant). Examples

include:

• Sexual dysfunctions associated

with diabetes mellitus57

• Sexual sequelae of child sexual

abuse35

Thus it seems as if an

association between “sex” and a medical disorder must be

demonstrated before

there is sufficient rationale to include sex-related questions in

a medical history. A closely

related issue is doubt among some health professionals

about the acceptability of sexual

issues in health care apart from disorders

that affect others (such as

STDs).

4. Talking with older patients

about sexual matters appears difficult for health

professional students. The age of

the student may be relevant, since many

are much younger than their

patients. The student may find that this situation

resembles talking with their

parents about the subject (an experience

that most would not have had and

that may be thought of as highly embarrassing

if it did occur). Avoidance of

discussing sexual issues with older

patients is particularly

unfortunate because some sexual difficulties clearly

become more common with

increasing age. For example, menopause in

women can result in discomfort

with intercourse, which, in turn, is explained

by decreased estrogen, resulting

in diminished vaginal lubrication.58 Menopausal

women will obviously not be well

served by the medical establish-

Not knowing what to do with the answer

is the most common reason given by

physicians for avoiding the topic of sex.

|

ment if they are not asked about

discomfort or pain with intercourse. Not

surprisingly, when women in

general are surveyed on the acceptability of

talking to a physician about

sexual concerns, almost three fourths think that

it is appropriate to do so.

Moreover, the response seems to be age related

in that approval increases with

age.59

5. Magnified concerns about

professional sexual misconduct and consequent licensure

problems result in reluctance by

some health professionals to initiate conversations

with patients about sexual

issues. The primary organization responsible

for medical malpractice insurance

in Canada has, in an exaggerated way,

cautioned their clients about

discussions with patients on the subject of sex and

has thereby magnified the already

difficult problem of health professional

restraint.60

6. The appropriateness of sex-related

questions in the acute stage of an illness may

be viewed by the health

professional as a dubious focus because of more pressing

patient concerns. An example is

when the patient has little opportunity for sexual

experiences with a partner (e.g.,

a situation that occurs when a patient is in

hospital). In this illustration,

sex is defined narrowly as related only to the function

of the genitalia.

7. Unfamiliarity with some sexual

practices (e.g., gay patients talking to a heterosexual

physician) may restrain the

health professional from introducing the

topic.

Why

Discussion Should Occur

(Box 1-2)

Reasons why discussions should

occur in a health care setting include the following:

1. HIV/AIDS, as everyone knows,

is a sexually transmitted disease that is also lethal.

It has become a powerful

(perhaps, the most convincing) stimulus for

sex history-taking by health

professionals (see introduction to Part I).61

Considering HIV/AIDS, prevention

is, at the moment, the best deterrent.

This, in turn, means talking to

patients about their sexual practices.

As used here, the term sexual

practices refers to:

• The types of sexual activities

engaged in by the patient, as well

Box 1-1

Why ‘Sex’ Questions Are Not Asked

1. Unclear what to do with the answers

2. Unfamiliarity with treatment approaches

2. • Uncertainty about the next question

2. Fear of offending patient

3. Lack of obvious justification

4. Generational obstacles

5. Fear of sexual misconduct charge

6. Sometimes perceived irrelevant

7. Unfamiliarity with some sexual practices

|

Considering HIV/AIDS, prevention is the

best deterrent. This means talking to

patients about their sexual practices.

|

as the nature of relationships

with sexual partners

• The characteristics of sexual partners

• The “toys” (mechanical

adjuncts such as vibrators) used in sexual

activities

• Methods used to prevent STD

transmission and conception

In the words of Hearst:

“Responsible primary care physicians

no longer have the option of

deciding whether to do AIDS

prevention; the question today is

how to do it. . . .”62 Health

professionals are simply not

fulfilling their role if inquiry is not

made about sexual practices, and

if, in the process, the opportunity for dispensing

preventive sexual advice is lost.

Physicians, in particular, are thought

to be in a unique position to

prevent HIV infection, since 70% of adults in the

United States visit a physician

at least once each year and 90% do so at least

once in five years.51

2. Many medical disorders such as

depression63 and diabetes57 are

known to disrupt

sexual function. A comprehensive

view of such disorders is plainly impossible

without also asking how a

patient’s sexual function is affected (see Chapter 8).

3. Treatments such as surgery64

or drugs65 can interrupt sexual function.

A health

professional should inquire about

drug side effects (see Chapter 8 and Appendix

III).

4. Inquiry into past sexual

events may be essential to understand the nature of a

disorder in the present. Such is

the case with lack of sexual desire after sexual

assault as an adult or child (See

Chapters 8 and 9).66

5. The observation that “. .

.sexual function is a lifelong capacity, not normally

diminished by middle or older

age” represents a change in social attitudes.67 The

aging of the population translates

into increasing expectations by many patients

regarding sexual function. These

hopes may conflict with the difficulty that

many young health professionals

experience in discussing sexual matters with

older people.

6. Sexual dysfunctions are common,

at least on an objective level.68 So, too,

are

sexual difficulties. Intuitively,

it seems reasonable for a health professional to ask

particularly about problems that

occur most frequently (sexual dysfunctions and

difficulties) as compared to

problems that are unusual.

7. On the topic of sex as well as

others, health professionals tend to be problem oriented.

This book and many others on the

same subject admittedly “focus on the

darker side. . .more than on its

brighter side”38 (p. 351). However, the “other side”

is what happens when “things go

right.” Laumann and colleagues (see introduction

to PART I) addressed this side of

sex in their chapter (brief by their own admission)

on the association between sex,

and health and happiness (pp.351-375).

Sexual activity and good health

are related. Of patients in the Laumann et al.

study who had no sexual partners

in the past 12 months, most (6% versus 2% of

the entire sample) were in poor

health.38 Sexual activity and happiness were

correlated.

Of those who considered

themselves “extremely or very happy” (compared

to those who were “generally

satisfied” or “unhappy”), three groups of

respondents were most prominent:

Physicians are thought to be in a unique

position to prevent HIV infection, since

70 percent of adults in the United States

visit a physician at least once each year

and 90% do so at least once in five

years

|

• Those who had one sexual

partner

• Those who had “sex” two to

three times per week

• Women who “always” or “usually”

experienced orgasm in partnered sex

(p. 358)

The association between “sex,”

emotional satisfaction, and physical pleasure was

examined also in the Laumann et

al. study38 (pp. 363-368). Those who found

their relationships “extremely or

very” pleasurable or satisfying were more often

the people who had one (versus

more than one) sex partner, especially if the

partner was a spouse or there was

a cohabitational relationship (p. 364). The

authors commented that while

“association is not causation (p. 364),” “the quality

of the sex is higher and the

skill in achieving satisfaction and pleasure is

greater when one’s limited

capacity to please is focused on one partner in the

context of a monogamous,

long-term partnership”(p. 365).

8. Why not? Masters and Johnson

asked this question (still germane more than 25

years later) in a medical journal

editorial that did not receive the attention that

it seemingly deserved.69

They were critical of the opinion that physicians apparently

needed special justification for

asking “sex” questions while paradoxically

being taught to ask questions

about everything else in the course of a general

medical examination. “The

biologic and behavioral professions must accept the

concept that sexual information

should be as integral a part of the routine medical

history as a discussion of bowel

or bladder function.”

9. Not including sexual matters

in a health history can sometimes be considered

negligent and possibly unethical.

An example is the second case history provided

in the introduction to PART I. In

that instance, the physician (in a “sin” of omission

rather than commission) clearly

failed the medical dictum of “do no

harm.”

Who (which patients) Should Be Asked About Sexual Issues?

Almost all patients should be

given the opportunity to talk about a sexual

concern in a health professional

setting. Providing such an opportunity

Box 1-2

Why Ask Questions About “Sex”?

1. Morbidity and mortality—STDs and

HIV/AIDS

2. Symptoms of illness

3. Treatment side effects

4. Past may explain present problems

5. Function potentially lifelong

6. Dysfunctions and difficulties are common

7. Association with health and happiness

8. Why not?

9. May be negligent if ignored

|

Almost all patients should be given the

opportunity to talk about a sexual concern

in a health professional setting.

|

does not mean asking a “sex”

question but rather using a method that involves asking if it’s

OK to ask a “sex” question (see

“Permission” in Chapter 2 and an example of a specific

permission question in Chapter

3).

Common sense dictates at least

two exceptions to routinely giving

everyone an opportunity to talk

about sexual issues. First, it obviously does not apply

to an emergency setting (unless,

for example, the emergency is sexual in nature, such

as sexual asphyxia [see Chapter 8

for definition]). Rather it applies to situations such

as the first few visits of an

“intake” procedure. Second, when applied to physicians, the

idea of routinely giving everyone

this opportunity relates more to generalists, that is,

primary care specialists (e.g.,

in medicine: family physicians, pediatricians, gynecologists,

and internists) and medical

specialists whose area of work is directly related to

sexual function (e.g.,

urologists). Providing an opportunity to talk about sexual issues

on a routine basis rather than a

selective basis does not apply to medical specialty areas

such as Ophthalmology and ENT

(ear, nose, and throat).

Where (in a health professional history) Should Questions

Be Asked About Sex?

Sometimes, a patient spontaneously

indicates that a sexual concern is the principal

reason for the visit. When this

occurs, the sexual problem obviously has priority. However,

such information usually has to

be elicited carefully. In a medical setting, three

different circumstances (not mutually

exclusive) exist in which this could happen:

1. The prime location in a

medical history for asking about sex-related information

is within a Review of Systems

(ROS [sometimes referred to as a

Functional Inquiry]; see

“Permission” in Chapter 2 for an example).

A ROS consists of a few questions

about each body system

to ensure that nothing is wrong

with a patient other than the

initial complaint(s). In such a

context, a few additional questions

about sexual concerns could be

easily included.

2. Another possibility for the

introduction of questions about sexual

issues is within a Personal and

Social History. For example, in the

process of asking about

relationships, one could ask about sexual

concerns.

3. A sex-related question could

be asked during a physical examination

(least desirable and an option

that is, obviously, unavailable

to nonphysicians). For example,

one could ask about genital function

in the process of examining

genitalia. In one sense, this situation

is easier for physicians, since

it seems that psychological

defenses of patients are

diminished when their clothes are off. However, the lowering

of defenses during a physical

examination can be hazardous to the patient

because questions about sexual

issues can be misinterpreted as a physician’s sexual

invitation and the patient’s

misconception could provoke a charge of sexual harassment

or misconduct. Although

sex-related questions during a physical examination

may represent a more efficient

use of professional time, the potential for

misunderstanding is sufficiently

great that this method should be avoided.

When Should Questions About Sex Be Asked?

The lowering of defenses during a physical

examination can be hazardous to the

patient because questions about sexual

issues can be misinterpreted as a sexual

invitation by the physician and the

patient’s misconception could provoke a

charge of sexual harassment or misconduct.

Although sex-related questions

during a physical examination may represent

a more efficient use of professional

time, the potential for misunderstanding

is sufficiently great that this

method should be avoided.

Green offered a clear and

sensible opinion on when questions should be asked

about sexual issues: “The optimal

time. . .is not when a patient’s initial visit has

been prompted by influenza,

otitis media and bronchitis. Nor is the appropriate

time the anniversary of the

physician-patient relationship. . .Delay in approaching

the topic communicates

discomfort. The effect when ‘the subject’ is finally broached

is comparable to the painfully

familiar scene of a father who initiates discussion of

the ‘facts of life’ with his son

on his 13th birthday.”1 Generally

speaking, the aphorism

of ‘the earlier the better’

should be applied. Screening questions (see Chapter

3) can be introduced after the

acute problem that initially led the patient to the

health professional has

disappeared or is under control.

If a problem is introduced in the

process of screening, more detailed diagnostically

oriented questions can be asked

on a subsequent occasion (see Chapter 4). The diagnostic

process may involve a physical

examination (see Chapter 6) and the use of

laboratory tests (see PART II).

Summary

Extrapolations from studies on

general aspects of health- related interviewing and history-

taking imply the following:

1. Concerning sexual issues,

teaching of skills by direct supervision and feedback

should be included in health

science educational programs

2. An interviewer can attend to

both factual information and feelings

3. Faculty modeling in obtaining

information about the patient’s psychosocial status

and risk factors is a significant

element in the learning process

When considering the integration

of sex-related questions into a general health history,

interviewing texts, books on

“Human Sexuality,” and journal articles appear to be

of limited practical help.

Studies in sex history-taking

have involved medical students, residents, and practicing

physicians. The studies can be

separated into ones that considered sex historytaking

in general and those that focused

on the specific subject of STDs. In the former

group, factors found to be

associated with positive attitudes toward sex history-taking

and conducting such a history

were:

1. Personal sexual experience

2. The belief that such questions

were relevant to the patient’s chief complaint

3. Feeling adequately trained

4. Confidence in taking a sex

history

5. Having previously taken a sex

history

6. Having spoken to a health

professional oneself about a sexual concern

7. Having a homosexual friend

8. Social and cultural factors

9. Skill training (as compared to

personal comfort and self-awareness)

Studies that focused on “sex”

history-taking as it applies to HIV/AIDS prevention

indicate that relevant questions

occur infrequently and inadequately. Previous “sexuality training”

appeared to

be helpful to physicians in caring for those already infected

with HIV but it was insufficient

in the process of preventing transmission, which, in

turn, required an inquiry into

the sexual practices of the patient.

Rather than attempting to define

a “sex” history (there are many such definitions),

it might be more productive to

simply talk about asking questions of patients about

sexual matters. One might

consider the introduction of such questions under the headings

of Who, What, When, Where, Why,

and How.

Reasons why “sex” history-taking

does not regularly occur include:

1. Not knowing what to do with

the answers

2. Concern that patients might

regard “sex” questions as intrusive

3. Lack of a sense of

justification

4. Difficulty in talking to older

patients about this subject

5. Concern about accusations of

sexual misconduct

6. The sense that such questions

are inappropriate in the context of other difficulties

manifested by the patient

7. Lack of familiarity with some

sexual practices

Reasons why “sex” questions should

occur in a health history include finding that:

1. Such questions provide an

opportunity to introduce HIV/AIDS prevention information

2. Disrupted sexual function may

be a symptom of a medical disorder or it may be

a side effect of its treatment

3. Past sexual history may help

explain the present

4. Sexual issues are important at

all stages of the life cycle

5. Sexual dysfunctions in

particular are quite common

6. Sexual function is related to

general health

7. There is no explanation for

not asking questions of a sexual nature

8. Not asking “sex” questions may

constitute negligence from a legal point of

view

The problem of who should be

asked questions about sexual issues can be resolved

by saying that almost everyone

should have the opportunity to talk about sexual concerns

if they so choose. Other than

situations in which a sexual problem is the main

issue that brought the patient to

the health professional, questions can be asked in the

context of a medical review of

systems (ROS) or a personal and social history. Physicians

may also ask questions during a

physical examination but caution should be

exercised because of the

possibility of misinterpretation of the intent and consequent

accusations of sexual misconduct.

It may be easier to say when the time to ask such

questions is not optimal than

when it is.

“Sex” questions are improper in

the midst of concern over some other issue that

brought the patient to the

attention of the health professional. (Questions about many

topics are reasonably omitted in

such situations). The context for “sex” questions is

after the acute problem subsides

and the professional is reviewing general aspects of

the patient’s health history.

The “how” (or methods used) of

asking “sex” questions is considered in detail in

Chapter 2 and is therefore not

included here. Similarly, the “what” (content) did not

form part of Chapter 1, since it

forms the content of Chapters 3, 4, and 5 and subsequent

portions of the book.

REFERENCES

1. Green R: Taking a sexual history. In Green

R (editor): Human sexuality: a health practitioner’s

text, ed 2,

Baltimore and London, 1979, Williams and Wilkins, pp 22-30.

2. Pomeroy WB, Flax CC, Wheeler CC: Taking

a sex history: interviewing and recording, New

York, 1982, The Free Press.

3. Risen CB: A guide to taking a sexual

history, Psychiatr Clin North Am 18(1):39-53, 1995.

4. Morrison J: The first interview: revised

for DSM-IV, New York, 1995, The Guilford Press.

5. Rutter M, Cox A: Psychiatric interviewing

techniques: 1. methods and measures, Br J

Psychiatry 138:273-282,

1981.

6. Maguire P et al: The value of feedback in

teaching interviewing skills to medical

students, Psychol Med 8:695- 704,

1978.

7. Maguire P, Fairbairn S, Fletcher C:

Consultation skills of young doctors: 1—benefits of

feedback training in interviewing as students

persist, Br Med J 292:1573-1576, 1986.

8. Stone H, Angevine M, Sivertson S: A model

for evaluating the history taking and

physical examination skills of medical

students, Med Teach 11:75-80, 1989.

9. Cox A, Holbrook D, Rutter M: Psychiatric

interviewing techniques VI. Experimental

study: eliciting feelings, Br J Psychiatry

139:144-152, 1981.

10. Hopkinson K, Cox A, Rutter M: Psychiatric

interviewing techniques III. Naturalistic

study: eliciting feelings, Br J Psychiatry

139:406-415, 1981.

11. Rutter M et al: Psychiatric interviewing

techniques IV. Experimental study: four

contrasting styles, Br J Psychiatry 138:456-465,

1981.

12. Cox A, Rutter M, Holbrook D: Psychiatric

interviewing techniques V. Experimental

study: eliciting factual information, Br J

Psychiatry 139:29-37, 1981.

13. Cox A, Holbrook D, Rutter M: Psychiatric

interviewing techniques VI. Experimental

study: eliciting feelings, Br J Psychiatry

139:144-152, 1981.

14. Cox A, Rutter M, Holbrook D: Psychiatric

interviewing techniques—a second

experimental study: eliciting feelings, Br

J Psychiatry 152:64-72, 1988.

15. Kaplan HS: Sex is psychosomatic

(editorial), J Sex Marital Ther 1:275-276, 1975.

16. Rezler AG, Woolliscroft JA, Kalishman SG:

What is missing from patient histories? Med

Teach 13:245-252,

1991.

17. Newell R: Interviewing skills for

nurses and other health care professionals, London, 1994,

Routledge.

18. Attarian P: The sexual history. In

Levinson D (editor): A guide to the clinical interview,

Philadelphia, 1987, W.B. Saunders Company, pp

226-234.

19. Long LG, Higgins PG, Brady D: Psychosocial

assessment: a pocket guide for data collection,

Norwalk, 1988, Appleton & Lange, pp

105-117.

20. Turnbull J: Interviewing the patient with

a sexual problem. In Leon RL: Psychiatric interviewing:

a primer,

ed 2, New York, 1989, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc., pp 151-155.

21. Kraytman M: The complete patient

history, ed 2, New York, 1991, McGraw-Hill, pp 468-470.

22. Lloyd M, Bor R: Communication skills

for medicine, Edinburgh, 1996, Churchill Livingstone,

pp 73-84.

23. Coulehan JL, Block MR: The medical

interview: a primer for students of the art, ed 2, Philadelphia,

1992, F.A. Davis Company, pp 217-224.

24. Shea SC: Psychiatric interviewing:

the art of understanding, Philadelphia, 1988, W.B. Saunders

Company.

25. Othmer EO, Othmer SC: The clinical

interview using DSM-IV, vol 1, Fundamentals and vol 2,

The difficult patient,

Washington, 1994, American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

26. Mackinnon RA: The psychiatric

interview in clinical practice, Philadelphia, 1971, W.B. Saunders

Company, pp 115- 117.

27. Cohen-Cole SA: The medical interview:

the three-function approach, St. Louis, 1991, Mosby-Year

Book, Inc., p 82.

28. MacKinnon RA, Yudofsky SC: Principles

of the psychiatric evaluation, Philadelphia, 1991, J.B.

Lippincott Company, pp 53-54.

29. Aldrich CK: The medical interview:

gateway to the doctor- patient relationship, New York, 1993,

The Parthenon Publishing Group, pp 102-104.

30. Semmens JP, Semmens FJ: The sexual

history and physical examination. In Barnard MU,

Clancy BJ, Krantz KE (editors): Human

sexuality for health professionals, Philadelphia, 1978,

W.B. Saunders Company, pp 27-43.

31. Marcotte DB: Sexual history taking. In

Nadelson CC, Marcotte DB (editors): Treatment

interventions in human sexuality,

New York, 1983, Plenum Press, pp 1-9.

32. Hogan RM: Human sexuality: a

nursing perspective, ed 2, Norwalk, 1985, Appleton-Century-

Crofts, pp 161-173.

33. Lewis CE: Sexual practices: are

physicians addressing the issues? J Gen Intern Med 5(5

suppl):S78-81, 1990.

34. Gabel LL, Pearsol JA: Taking an effective

sexual and drug history: a first step in HIV/

AIDS prevention, J Fam Prac 37:185-187,

1993.

35. Wyatt G: Child sexual abuse and its

effects on sexual functioning, Annual Review of Sex

Research 2:249-266,

1991.

36. Alexander B: Taking the sexual history, Am

Fam Physician 23:147, 1981.

37. Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE: Sexual

behavior in the human male, Philadelphia and

London, 1949, W.B. Saunders.

38. Laumann EO et al: The social

organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States,

Chicago, 1994, The University of Chicago

Press.

39. Johnson AM et al: Sexual attitudes and

lifestyles, Oxford, 1994, Blackwell Scientific

Publications.

40. Spira A, Bajos N, and the ACSF group: Sexual

behavior and AIDS, Brookfield, 1994, Ashgate

Publishing Company.

41. Vollmer SA, Wells KB: How comfortable do

first-year medical students expect to be

when taking sexual histories? Med Educ 22:418-425,

1988.

42. Vollmer SA, Wells KB: The preparedness of

freshman medical students for taking sexual

histories, Arch Sex Behav 18:167-177,

1989.

43. Vollmer SA et al: Improving the preparation

of preclinical students for taking sexual

histories, Acad Med 64:474-479, 1989.

44. Merrill JM, Laux LF, Thornby JI: Why

doctors have difficulty with sex histories, South

Med J 83:613-617,

1990.

45. Hunt AD, Litt IF, Loebner M: Obtaining a

sexual history from adolescent girls: a

preliminary report of the influence of age

and ethnicity, J Adolesc Health Care 9:52-54,

1988.

46. Liese BS et al: An experimental study of

two methods for teaching sexual history taking

skills, Fam Med 21:21-24, 1989.

47. Ende JE, Rockwell S, Glasgow M: The

sexual history in general medicine practice, Arch

Intern Med 144:558-561,

1984.

48. Calabrese LH et al: Physicians’

attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding AIDS healthcare

promotion, Arch Intern Med 151:1157-1160,

1991.

49. Bresolin LB et al: Attitudes of U.S.

primary care physicians about HIV disease and AIDS,

AIDS Care 2:117-125,

1990.

50. Boekeloo BO et al: Frequency and

thoroughness of STD/HIV risk assessment by

physicians in a high-risk metropolitan area, Am

J Public Health 81:1645-1648,

1991.

51. Ferguson KJ, Stapleton JT, Helms CM:

Physicians’ effectiveness in assessing risk for

human immunodeficiency virus infections, Arch

Intern Med 151:561-564, 1991.

52. Curtis JR et al: Internal medicine

residents’ skills at identification of HIV-risk behavior

and HIV-related disease, Acad Med 69:S45-47,

1994.

53. Lewis CE, Montgomery K: The AIDS-related

experiences and practices of primary care

physicians in Los Angeles: 1984-89, Am J

Public Health 80:1511-1513, 1990.

54. McCance KL, Moser R Jr., Smith KR: A

survey of physicians’ knowledge and application

of AIDS prevention capabilities, Am J Prev

Med 7(3):141-145, 1991.

55. Russell NK et al: Extending the skills

measured with standardized patient examinations:

using unannounced simulated patients to

evaluate sexual risk assessment and risk

reduction skills of practicing physicians, Acad

Med 66 (Sept Suppl), S37-S39, 1991.

56. Bowman MA et al: The effect of

educational preparation on physician performance with

a sexually transmitted disease-simulated

patient, Arch Intern Med 152:1823-1828, 1992.

57. Schiavi RC et al: Diabetes mellitus and

male sexual function, Diabetologia 36:745-751,

1993.

58. Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human sexual

response, Boston, 1966, Little, Brown and

Company, p 240.

59. Maurice WL, Sheps SB, Schechter MT: Physician

sexual contact with patients: 2. A public survey

of women in British Columbia.

Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Sex Therapy

and Research, New York, March 1995.

60. Information letter, Can Med

Protect Assoc 7:2, 1992.

61. Canadian AIDS Society. Safer sex

guidelines: health sexuality and HIV, Ottawa, 1994, Can AIDS

Society.

62. Hearst N: AIDS risk assessment in primary

care, J Am Board Fam Pract 7(1):44-48, 1994.

63. Nofzinger EA et al: Sexual function in

depressed men, Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:24-30, 1993.

64. Yavetz H et al: Retrograde ejaculation, Hum

Reprod 93:381-386, 1994.

65. Barnes TRE, Harvey CA: Psychiatric

drugs and sexuality. In Riley AJ, Peet M, Wilson C

(editors): Sexual pharmacology, New

York, 1993, Oxford University Press.

66. Becker JV et al: Level of postassault

sexual functioning in rape and incest victims, Arch Sex

Behav 15:37-49,

1986.

67. Tiefer L, Melman A: Comprehensive

evaluation of erectile dysfunction and medical

treatments. In Leiblum SR, Rosen RC

(editors): Principles and practice of sex therapy: update for

the 1990s,

ed 2, New York, 1989, The Guilford Press, p 208.

68. Frank E, Anderson C, Rubenstein D:

Frequency of sexual dysfunction in normal couples,

N Engl J Med 299:111-115,

1978.

69. Masters WH, Johnson VE: Undue distinction

of sex, N Engl J Med 281:1422-1423, 1969.