Communication and Information Sector

SECTION 1. The Development of Open Access to Scientific Information and Research.

1.1 The development of scientific communication

1.2 The development of Open Access to scientific information

1.4 Target content for Open Access

SECTION 2. Approaches to Open Access

2.1 Open Access repositories: the 'green' route to Open Access

2.2 Open Access journals: the 'gold' route to Open Access

SECTION 3. The Importance of Open Access

3.3 Open Access in the wider 'open' agenda

SECTION 4. The Benefits of Open Access

4.1 Enhancing the research process

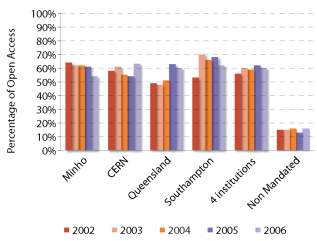

4.2 Visibility and usage of research

5.1 The context: traditional business models in scientific communication

5.2 New business models in scientific communication

SECTION 6. Copyright and Licensing

SECTION 7. Strategies to Promote Open Access.

7.3 Infrastructural approaches

7.4 Organisations engaged in promoting Open Access

SECTION 8. Policy Framework for Open Access

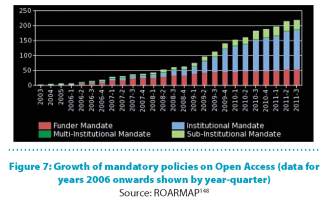

8.1 Development and growth of policies

SECTION 9. Summary Policy Guidelines

9.2 Guidelines for governments and other research funders

9.3 Guidelines for Institutional policy-makers

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND REFERENCES

GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

APPENDIX 2. Model policies for institutions, funders and governments

A2.1 Type 1: immediate deposit, no waiver ("Liège-style" policy)

A2.2 Type 2: rights-retention policies

POLICY GUIDELINES FOR THE DEVELOPMENT AND PROMOTION OF OPEN ACCESS

FOREWORD

As stated in its Constitution, UNESCO is dedicated to 'maintain, increase and diffuse knowledge' Therefore, part of its mission is to build knowledge societies by fostering universal access to information and knowledge through information and communication technologies (ICTs). The Knowledge Societies Division of the Communication and Information Sector is engaged in promoting multilingualism in cyberspace, access to information for people with disabilities, developing national policies for the information society, preservation of documentary heritage, and use of ICTs in education, science and culture, including Open Access to scientific information and research. Open Access is at the heart of the overall effort by the Organization to build peace in the minds of men and women.

Through Open Access, researchers and students from around the world gain increased access to knowledge, publications receive greater visibility and readership, and the potential impact of research is heightened. Increased access to, and sharing of knowledge leads to opportunities for equitable economic and social development, intercultural dialogue, and has the potential to spark innovation. The UNESCO Open Access strategy approved by the Executive Board in its 187th session and further adopted by the 36th General Conference identified up-stream policy advice to Member States in the field of Open Access as the core priority area amongst others. These policy guidelines are the result of an iterative process undertaken by the UNESCO Secretariat and Dr. Alma Swan, a leading expert in the field of Open Access, to revise the preliminary report based on the online consultation undertaken in the Open Access Community of the WSIS Knowledge Communities for peer review in September 2011.

I believe that this comprehensive document will be broadly useful to decision- and policy-makers at the national and international levels. However, it should be stressed that they are meant to be strictly advisory; they are not intended as a prescriptive or normative instrument. Further, I hope that this publication will also serve as a reference point for all stakeholders to clarify basic doubts in the field of Open Access. I encourage you to provide us your feedback and comments based on your experience of applying the ideas covered in this publication to further improve it in future editions.

Janis Karklins Assistant Director-General for Communication and Information, UNESCO

INTRODUCTION

Open Access to Scientific Information and Research

Scientific information is both a researcher's greatest output and technological innovation's most important resource. Open Access (OA) is the provision of free access to peer-reviewed, scholarly and research information to all. It requires that the rights holder grants worldwide irrevocable right of access to copy, use, distribute, transmit, and make derivative works in any format for any lawful activities with proper attribution to the original author. Open Access uses Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to increase and enhance the dissemination of scholarship. OA is about Freedom, Flexibility and Fairness.

The rising cost of journal subscription is a major force behind the emergence of the OA movement. The emergence of digitisation and Internet has increased the possibility of making information available to anyone, anywhere, anytime, and in any format. Through Open Access, researchers and students from around the world gain increased access to knowledge, publications receive greater visibility and readership, and the potential impact of research is heightened. Increased access to and sharing of knowledge leads to opportunities for equitable economic and social development, intercultural dialogue, and has the potential to spark innovation. Open Access is at the heart of UNESCO's goal to provide universal access to information and knowledge, focussing particularly on two global priorities: Africa and Gender equality. In all the work UNESCO does in the field of OA, the overarching goal is to foster an enabling environment for OA in the Member States so that the benefits of research are accessible to everyone through the public Internet.

The Constitution of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Article I, Clause

2 states one of the purposes and functions of the Organisation as:

(c) Maintain, increase and diffuse knowledge: By assuring the conservation and protection of the world's inheritance of books, works of art and monuments of history and science, and recommending to the nations concerned the necessary international conventions;

By encouraging cooperation among the nations in all branches of intellectual activity, including the international exchange of persons active in the fields of education, science and culture and the exchange of publications, objects of artistic and scientific interest and other materials of information;

By initiating methods of international cooperation calculated to give the people of all countries access to the printed and published materials produced by any of them.

While UNESCO's mission is to contribute to the building of peace, the eradication of poverty, sustainable development and intercultural dialogue through education, the sciences, culture, communication and information, the Organisation has the following five overarching objectives:

■ Attaining quality education for all and lifelong learning

■ Mobilising science knowledge and policy for sustainable development

■ Addressing emerging social and ethical challenges

■ Fostering cultural diversity, intercultural dialogue and a culture of peace

■ Building inclusive knowledge societies through information and communication

The organisation also has two global priorities - Africa and Gender Equality within its overall mandate, as areas of focus. Thus, in the areas of its competence, UNESCO's role is to improve access to information and knowledge for the Member States through appropriate use of information and communication technologies. While the programme sectors engage in the specific area of UNESCO's competence, the Communication and Information sector, especially the Knowledge Societies Division (KSD) engages in creating an enabling environment in Member States to facilitate access to information and knowledge in order to build inclusive knowledge societies. Open Access to scientific information and research is one of the many programmes on which the KSD works to increase access to information and knowledge. Some of the other related areas where UNESCO works are:

Free and Open Source Software (FOSS)

In the area of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), UNESCO fulfils its basic functions of a laboratory of ideas and a standard-setter to forge universal agreements on emerging ethical issues by supporting the development and use of open, interoperable, non-discriminatory standards for information handling and access as important elements in developing effective infostructures that contribute to democratic practices, accountability and good governance. Recognising that software plays a crucial role in access to information and knowledge, UNESCO supported the development and distribution of software such as the Micro CDS/ISIS1 (information storage and retrieval software) and Greenstone2 (digital library software). FOSS is the engine for the growth and development of Open Access, and UNESCO encourages community approaches to software development.

Preservation of Digital Heritage

Preservation of digital cultural heritage, including digital information is a priority area for UNESCO. Digital preservation consists of the processes aimed at ensuring the continued accessibility of digital materials. Making information that are preserved accessible to citizens is facilitated through the appropriate use of a combination of software and hardware tools. UNESCO's Charter on the Preservation of the Digital Heritage (2003) states that

"the purpose of preserving the digital heritage is to ensure that it remains accessible to the public. Accordingly, access to digital heritage materials, especially those in the public domain, should be free of unreasonable restrictions. At the same time, sensitive and personal information should be protected from any form of intrusion”

1 http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/access-to-knowledge/free-and-open-source-software-foss/cdsisis/

UNESCO's Memory of the World (MoW) programme aims at preserving world's documentary heritage by making it permanently accessible to all without hindrance. The mission of the Memory of the World Programme is:

■ To facilitate preservation, by the most appropriate techniques, of the world's documentary heritage.

■ To assist universal access to documentary heritage.

■ To increase awareness worldwide of the existence and significance of documentary heritage.

Access to high quality education is key to the building of peace, sustainable social and economic development, and intercultural dialogue. Open Educational Resources (OER) provide a strategic opportunity to improve access to quality education at all levels, and increase dialogue, knowledge sharing and capacity building. In the education and research ecosystem, OER and OA forms two important interventions that works in an integrated fashion to promote the quality of learning and generate new knowledge. The term OER was coined at UNESCO in the 2002 Forum on the Impact of Open Courseware for Higher Education in Developing Countries.

Information for All Programme (IFAP)

KSD also hosts the intergovernmental programme - Information for All Programme (IFAP) that is engaged in reducing the gap between information have and have not in North and South. The IFAP seeks to:

■ promote international reflection and debate on the ethical, legal and societal challenges of the information society;

■ promote and widen access to information in the public domain through the organisation, digitisation and preservation of information;

■ support training, continuing education and lifelong learning in the fields of communication, information and informatics;

■ support the production of local content and foster the availability of indigenous knowledge through basic literacy and ICT literacy training;

■ promote the use of international standards and best practices in communication, information and informatics in UNESCO's fields of competence; and

■ promote information and knowledge networking at local, national, regional and international levels.

The World Summit on the Information Society3 (WSIS), Geneva (2003) declared that "the ability for all to access and contribute information, ideas and knowledge is essential in an inclusive Information Society” It further emphasised that sharing of global knowledge for development can be enhanced by removing barriers to equitable access to information. While a rich public domain is an essential element for the growth of the Information Society, preservation of documentary records and free and equitable access to scientific information is necessary for innovation, creating new business opportunities and provide access to collective memory of the civilizations.

In the context of Open Access, the Summit proclaimed:

28. We strive to promote universal access with equal opportunities for all to scientific knowledge and the creation and dissemination of scientific and technical information, including open access initiatives for scientific publishing.

Two of the Action Lines of the WSIS (Action Line 3:

Access to information and knowledge and Action Line 7: E-Science) have been involved in promoting Open Access to peer-reviewed information and research data through their interventions and engagements with the stakeholders.

Objective of this Document

The overall objective of the Policy Guidelines is to promote Open Access in Member States by facilitating understanding of all relevant issues related to Open Access. Specifically, it is expected that the document shall:

■ Enable Member State institutions to review their position on access to scientific information in the light of the Policy Guidelines;

■ Assist in the choice of appropriate OA policy in the specific contexts of Member States; and

■ Facilitate adoption of OA policy in research funding bodies and institutions by integrating relevant issues in the national research systems.

Thus, the Policy Guidelines are not prescriptive in nature, but are suggestive to facilitate knowledge-based decisionmaking to adopt OA policies and strengthen national research systems.

The content of the Policy Guidelines is organized in to nine

sections:

■ Section 1: The Development of Open Access to Scientific Information and Research, gives an overview of the definitions used, and the history of the OA movement

- Budapest-Bethesda-Berlin.

■ Section 2: Approaches to Open Access, enumerates the 'green' and 'gold' routes to OA.

■ Section 3: The Importance of Open Access, explains how OA is important for scholars, research institutions and for developing knowledge societies.

■ Section 4: The Benefits of Open Access, emphasizes that OA enhances research process, improves visibility and usage of research works, and therefore, the impact of research works is also increased through citations and impact outside the academia.

■ Section 5: Business Models, analyses the traditional business models in scientific communications and describes the new emerging models in the context of OA.

■ Section 6: Copyright and Licensing, provides an overview of the legal issues in a non-legal language to explain that copyright is at the heart of OA. Copyright owners consent is essential to make OA happen, and authors and creators can retain rights to increase use of their works through different mechanisms, including Creative Commons licensing.

■ Section 7: Strategies to Promote Open Access, describes policy- focused, advocacy-based and infrastructural approaches to OA. While all the approaches are important, it also lists a number of organizations engaged in promoting OA.

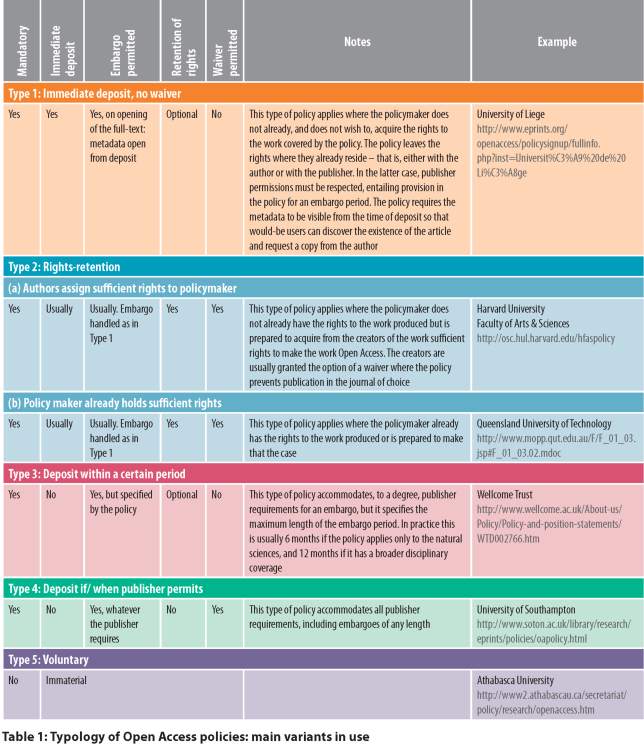

■ Section 8: Policy Framework for Open Access, presents an overview of the growth of policies, and a critical appraisal of the issues affecting OA policies. It also presents a typology of OA policies to explain the difference in different types of policies adopted around the world. The chapter should be seen along-with the examples in Appendix-1.

■ Section 9: Summary Policy Guidelines, is the key section of this document and explain the various components that a standard policy should consider, and suggests the best policy decision to be included. This section should also be seen along-with the templates in Appendix-2.

The Policy Guidelines also gives a detailed bibliography and glossary of terms and abbreviations used at the end. An executive summary is also there in the beginning to provide an overview of the document to help a quick understanding, though it is recommended that you read the sections for detail.

Using the Policy Guidelines

The Policy Guidelines can be used by individuals as a basic text on Open Access and related policies. While we recommend that beginners to the world of Open Access should read it from cover to cover, people having some understanding of OA may like to start reading from any of the sections. Decision-makers, administrators and research managers should focus on Sections 8 and 9 that capture all relevant issues of OA policy development. At the end of this document, you will find examples of different types of OA policies (Appendix 1), and three policy templates (Appendix 2) to choose and adopt. While every institution may have their unique process of policy adoption, we recommend a more democratic, consultative and open approach to adopt Open Access policy, as success of the policy implementation will depend on the ownership of the stakeholders to deposit their work and/or publish in OA journals. We are sure that the Policy Guidelines will be useful to you, and we are interested in listening to your experiences and feedback. Please fill the attached feedback form at page 75-76 and return it to us to help improve the Policy Guidelines and also share your experiences with others.

Dr. Sanjaya Mishra Programme Specialist (ICT in Education, Science and Culture) Knowledge Societies Division Communication and Information Sector United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

These Guidelines provide an account of the development of Open Access, why it is important and desirable, how to attain it, and the design and effectiveness of policies.

Open Access is a new way of disseminating research information, made possible because of the World Wide Web. The development of the concept is summarised as follows:

■ The Web offers new opportunities to build an optimal system for communicating science - a fully linked, fully interoperable, fully-exploitable scientific research database available to all

■ Scientists are using these opportunities both to develop Open Access routes for the formal literature and for informal types of communication

■ For the growing body of Open Access information, preservation in the long-term is a key issue

■ Essential for the acceptance and use of the Open Access literature are new services that provide for the needs of scientists and research managers

■ There are already good, workable, proven-in-use definitions of Open Access that can be used to underpin policy

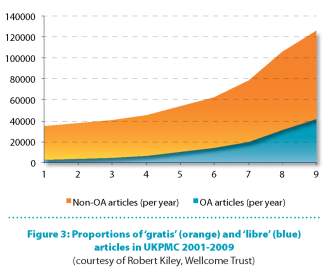

■ There is also a distinction made between two types of Open Access - gratis and libre- and this distinction also has policy implications

■ Two practical routes to Open Access ('green' and 'gold') have been formally endorsed by the research community

■ The primary, and original, target for Open Access was the journal literature (including peer-reviewed conference proceedings). Masters and doctoral theses are also welcome additions to this list and the concept is now being widened to include research data and books

There is already considerable infrastructure in place to enable Open Access although in some disciplines this is much further advanced than others. In these cases,

cultural norms have changed to support Open Access. Open Access is achieved by two main routes:

■ Open Access journals, the 'gold' route to Open Access, are a particularly successful model in some disciplines, and especially in some geographical communities

■ The 'g reen' route, via repositories can capture more material, faster, if the right policies are put in place

Additionally, 'hybrid' Open Access is offered by many publishers: this is where a fee can be paid to make a single article Open Access in an otherwise subscription-based journal. In some cases, the publisher will reduce the subscription cost in line with the new revenue coming in from Open Access charges, but in most cases this is not offered. The practice of accruing new revenue from Open Access charges without reducing the subscription price is known as 'double dipping'

There are a number of issues that contribute to the importance of Open Access:

■ There is a problem of accessibility to scientific information everywhere

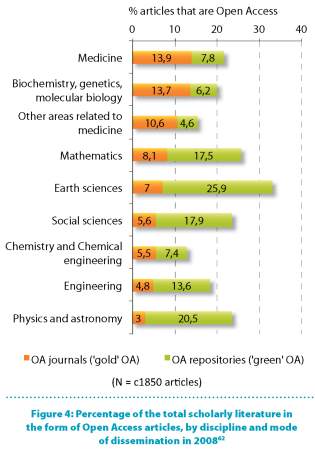

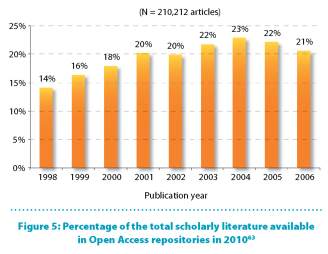

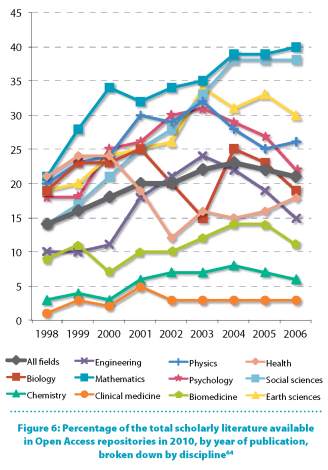

■ Levels of Open Access vary by discipline, and some disciplines lag behind considerably, making the effort to achieve Open Access even more urgent

■ Access problems are accentuated in developing, emerging and transition countries

■ There are some schemes to alleviate access problems in the poorest countries but although these provide access, they do not provide Open Access: they are not permanent, they provide access only to a proportion of the literature, and they do not make the literature open to all but only to specific institutions

■ Open Access is now joined by other concepts in a broader 'open' agenda that encompasses issues such as Open Educational Resources, Open Science, Open Innovation and Open Data

■ Some initiatives aimed at improving access are not Open Access and should be clearly differentiated as something different

■ Open Access improves the speed, efficiency and efficacy of research

■ Open Access is an enabling factor in interdisciplinary research

■ Open Access enables computation upon the research literature

■ Open Access increases the visibility, usage and impact of research

■ Open Access allows the professional, practitioner and business communities, and the interested public, to benefit from research

As Open Access has grown, new business models have been developed - for journal publishing, for Open Access repositories, book publishing and services built to provide for new needs, processes and systems associated with the new methods of dissemination.

The dissemination of research depends upon the copyright holder's consent and this can be used to enhance or hamper Open Access. Copyright is a bundle of rights: authors of journal articles normally sign the whole bundle of rights over to the publisher, though this is not normally necessary.

Authors (or their employers or funders) can retain the rights they need to make the work Open Access, assigning to the journal publisher the right to publish the work (and to have the exclusive right to do this, if required).

Such premeditated retention of sufficient rights to enable Open Access is the preferable course of action rather than seeking permission post-publication.

Formally licensing scientific works is good practice because it makes clear to the user - whether human or machine - what can be done with the work and by that can encourage use. Only a minor part of the Open Access literature is formally licensed at present: this is the case even for Open Access journal content.

Creative Commons licensing is best practice because the system is well-understood, provides a suite of licences that cover all needs, and the licences are machine-readable.

In the absence of such a licence, legal amendments to copyright law will be necessary in most jurisdictions to enable text-mining and data-mining research material.

Policy development is still a relatively new activity with respect to research dissemination. Policies may request and encourage provision of Open Access, or they may

require it. Evidence shows that only the latter, mandatory, type accumulate high levels of material. Evidence also shows that researchers are happy to be mandated on this issue.

The issues that an Open Access policy should address are as follows:

■ Open Access routes: policies can require 'green'

Open Access by self-archiving but to preserve authors' freedom to publish where they choose policies should only encourage 'gold' Open Access through publication in Open Access journals

■ Deposit locus: deposit may be required either in institutional or central repositories. Institutional policies naturally specify the former: funder policies may also do this, or may in some cases specify a particular central repository

■ Content types covered: all policies cover journal articles: policies should also encourage Open Access for books: funder polices are increasingly covering research data outputs

■ Embargoes: Policies should specify the maximum embargo length permitted and in science this should be 6 months at most: policies should require deposit at the time of publication with the full-text of the item remaining in the repository, but closed, until the end of the embargo period

■ Permissions: Open Access depends on the permission of the copyright holder, making it vulnerable to publisher interests. To ensure that Open Access can be achieved without problem, sufficient rights to enable that should be retained by the author or employer and publishers assigned a 'Licence To Publish'. Where copyright is handed to the publisher, Open Access will always depend upon publisher permission and policies must acknowledge this by accommodating a 'loophole' for publishers to exploit

■ Compliance with policies: compliance levels vary according to the strength of the policy and the ongoing support that a policy is given: compliance can be improved by effective advocacy and, where necessary, sanctions

■ Advocacy to support a policy: there are proven advocacy practices in support of an Open Access policy: policymakers should ensure these are known, understood, and appropriate ones implemented

■ Sanctions to support a policy: both institutions and funders have sanctions that can be used in support of an Open Access policy: policymakers should ensure that these are identified, understood and appropriate ones implemented where other efforts fail to produce the desired outcome

■ Waivers: where a policy is mandatory authors may not always be able to comply. A waiver clause is necessary in such policies to accommodate this

■ 'Gold' Open Access: where a funder or institution has a specific commitment with respect to paying 'gold' article-processing fees, this should be stated in the policy

1.1 The development of scientific communication

The primary purposes of a formal publishing system through journals or books are so that scholars may establish their right to the intellectual property contained in the articles, so that authors can lay claim to be the first to conduct the work and present its findings, and to operate a quality control system through peer review that endeavours to guarantee that the work published is bona fide, original and properly conducted.

The beginning of the modern era of scientific communication can be traced back to the publication in 1665 of the first issues of both the JournaldesSgavans in Paris and the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (of London). The number of scholarly journals grew very slowly at first, with 100 extant titles in the mid 1800s and approximately linear growth until the latter half of the 20th century when numbers grew very rapidly, reflecting massive investment in science that increased project funding and researcher numbers.

The number of peer-reviewed journals currently in publication is generally agreed to be around 25,0004: there are probably many more local and regional peer-reviewed publications in addition to this, as well as publications that do not undertake formal peer review.

Over three centuries there was little change in the system apart from in intensity of activity, but in the mid-20th century computing developments offered opportunities for new ways of communicating about research. By the 1970s, scientists at Bell Laboratories were posting their findings on electronic archives that offered file transfer protocol (ftp) access for other scientists. This may seem

insignificant, but represents a major shift: now, scientists were permitting access to their own files on remote computers and accessing those of other scientists in the same way. The age of digital scientific communication had begun, though it remained largely the domain of computer scientists until the advent of the World Wide Web in the late 1980s3. The development of graphical Web browsers subsequently enabled anyone with a computer and online access to communicate with anyone else with a computer and online access.

Now, with the only limiting factors being the technological limits of bandwidth and computer power, scientists can take advantage of instant communication. They are doing so in increasingly diverse ways through informal, self- or community-regulated networks utilising tools such as blogs, wikis, discussion groups, podcasts, webcasts, virtual conferences and instant messaging systems. These developments are changing both the character of science communication in many ways and scientists' expectations of a science communication system. We can expect continuing evolution in this area.

At the same time, the formal components of the scientific publishing system have moved to the Web and while some scientific journals are still published in print to accompany the electronic version, new journals are mostly born electronic. At the moment, at least, journals still represent the formal record of science. To improve their functionality, over the past decade or so an array of new features have been added to such journals, such as extensive hyper-linking within the text to other articles, graphics and datasets. In addition, some of the early worries of librarians (and some scientists) about the longterm preservation of electronic journals have been at least partly allayed by arrangements between (some) publishers and national libraries and by international developments such as CLOCKSS4.

Alongside the move to the Web of journals there has been the development of specialised Web-based search-and- discovery tools to enable scientists to identify and locate articles of relevance to their work. Some of these tools are electronic versions of previous, paper-based services, others are new services altogether, such as Web search engines (for example, Google Scholar).

4 This is the number indexed by Ulrich'sPeriodicals Directory

1.2 The development of Open Access to scientific information

The early use of the Internet by computer scientists was the forerunner of true Open Access. They made their findings freely available for other computer scientists to use and build on. But theirs was a comparatively rudimentary system and was open only to a discrete community. The Web, however, offered the possibility for scientists to make their work available to all who might wish to use it, and though academic research might be viewed as being primarily of use to academic scientists, there are other constituencies that benefit from it as well - independent researchers, the professional and practitioner communities, industry and commerce.

In 1991, the high-energy physics preprint server, arXiv5 (preprints are the pre-peer review version of journal articles) was established and the practice of self-archiving (depositing in an Open Access archive) of scientific articles took root in that community. Later in that decade, Citeseer6, a citation-linked index of the computer science literature was developed to harvest articles from websites and repositories where they were being selfarchived by the computer science community. These two rapidly-growing collections7 of openly-available material demonstrated the demand for access to that literature - usage is extremely high - and showed the way for the rest of the scientific disciplines.

5 Developed by Berners-Lee (1989) see full reference in bibliography.

6 Controlled LOCKSS (Lots of Copies Keep Stuff Safe), a community-governed initiative to preserve scholarly material in a sustainable, geographically- distributed, dark archive: http://www.clockss.org/clockss/Home

7 The server was initially hosted at the Los Alamos Laboratory in the USA, and moved to Cornell University in 2001: www.arxiv.org It contains around 750,000 full-text documents and 75,000 new submissions each year. It serves approximately 1 million full-text downloads to around 400,000 individual users each week: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v476/ n7359/full/476145a.html

8 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/

While many disciplines did not follow suit, there was subsequent development of Open Access collections in biomedicine in the form of PubMed Central8 and in economics (RePEC9 and similar services). These services are all excellent examples of opening up the literature in specific disciplines, but there remains a great deal of science not covered by them and so much work to be done in extending Open Access to these areas.

At the same time as repositories were developing as locations for Open Access material, the alternative type of Open Access dissemination vehicle was also on the rise - Open Access journals. These are journals of a new type: they make their contents freely available online (though they may still charge subscriptions for printed versions) and employ a variety of business models to cover their costs. There are currently nearly 7,000 journals listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals, a service that is compiling a verified, searchable index of this type of publication. Some of these journals head their categories in the impact factor rankings published by Thomson Reuters12.

In some cases, books are also available as Open Access publications and in fact one of the earliest experiments in Open Access was by the National Academies Press which, in 1994, began making its books freely available online while selling print copies (a model it still uses though with some refinements). Recent developments in this area have been extensive: of note are the many advances by university presses to find a sustainable model for producing their outputs in Open Access form13, the establishment of a shared production platform and Open Access digital library for publishers of books in the humanities in Europe14, and with commercial publishers entering the scene15.

With these developments, the need to advocate a clear message to the whole scientific community led to the development of a formal definition of Open Access.

1.3 Defining Open Access

1.3.1 The Budapest Open Access Initiative

Although there have been several different attempts at formally defining Open Access, the working definition used by most people remains that of the Budapest Open Access Initiative (BOAI, 200216) which was released following a meeting in Budapest in December 2001. The Initiative is worded as follows:

An old tradition and a new technology have converged to make possible an unprecedented public good. The old tradition is the willingness of scientists and scholars to publish the fruits of their research in scholarlyjournals without payment, for the sake of inquiry and knowledge. The new technology is the internet. The public good they make possible is the world-wide electronic distribution of the peer-reviewed journal literature and completely free and unrestricted access to it by all scientists, scholars, teachers, students, and other curious minds. Removing access barriers to this literature will accelerate research, enrich education, share the learning of the rich with the poor and the poor with the rich, make this literature as useful as it can be, and lay the foundation for uniting humanity in a common intellectual conversation and quest for knowledge.

For various reasons, this kind of free and unrestricted online availability, which we will call open access, has so far been limited to small portions of the journal literature. But even in these limited collections, many different initiatives have shown that open access is economically feasible, that it gives readers extraordinary power to find and make use of relevant literature, and that it gives authors and their works vast and measurable new visibility, readership, and impact. To secure these benefits for all, we call on all interested institutions and individuals to help open up access to the rest of this literature and remove the barriers, especially the price barriers, that stand in the way. The more who join the effort to advance this cause, the sooner we will all enjoy the benefits of open access.

The literature that should be freely accessible online is that which scholars give to the world without expectation of payment. Primarily, this category encompasses their peer-reviewed journal articles, but it also includes any as-yet un-reviewedpreprints that they might wish to put online for comment or to alert colleagues to important research findings. There are many degrees and kinds of wider and easier access to this literature. By "open access" to this literature, we mean its free availability on the public internet, permitting any users to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal, or technical barriers other than those inseparable from gaining access to the internet itself. The only constraint on reproduction and distribution, and the only role for copyright in this domain, should be to give authors control over the integrity of their work and the right to be properly acknowledged and cited.

While the peer-reviewed journal literature should be accessible online without cost to readers, it is not costless to produce. However, experiments show that the overall costs of providing open access to this literature are far lower than the costs of traditional forms of dissemination. With such an opportunity to save money and expand the scope of dissemination at the same time, there is today a strong incentive for professional associations, universities, libraries, foundations, and others to embrace open access as a means of advancing their missions. Achieving open access will require new cost recovery models and financing mechanisms, but the significantly lower overall cost of dissemination is a reason to be confident that the goal is attainable and not merely preferable or utopian.

9 CiteSeer contains more than 750,000 documents and fulfils 1.5 million viewing requests per day. arXiv contains nearly 700,000 documents and sees over a million visits per day.

10 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/ There are also national versions of PubMed Central (such as UK PubMed Central: http://ukpmc.ac.uk/)

12 Web of Knowledge Journal Citation Reports: http://wokinfo.com/products_ tools/analytical/jcr/

13 OASIS (Open Access Scholarly Information Sourcebook): University presses and Open Access Publishing: http://www.openoasis.org/index. php?option=com_content&view=article&id=557&Itemid=385

14 OAPEN (Open Access publishing in European Networks): http://www. oapen.org/home

15 For example, Bloomsbury Academic: http://www.bloomsburyacademic. com/

To achieve open access to scholarlyjournal literature, we recommend two complementary strategies.

I. Self-Archiving: First, scholars need the tools and assistance to deposit their refereed journal articles in open electronic archives, a practice commonly called, self-archiving. When these archives conform to standards created by the Open Archives Initiative, then search engines and other tools can treat the separate archives as one. Users then need not know which archives exist or where they are located in order to find and make use of their contents.

II. Open-access Journals: Second, scholars need the means to launch a new generation of journals committed to open access, and to help existing journals that elect

to make the transition to open access. Because journal articles should be disseminated as widely as possible, these new journals will no longer invoke copyright to restrict access to and use of the material they publish. Instead they will use copyright and other tools to ensure permanent open access to all the articles they publish. Because price is a barrier to access, these new journals will not charge subscription or access fees, and will turn to other methods for covering their expenses. There are many alternative sources of funds for this purpose, including the foundations and governments that fund research, the universities and laboratories that employ researchers, endowments set up by discipline or institution, friends of the cause of open access, profits from the sale of addons to the basic texts, funds freed up by the demise or cancellation of journals charging traditional subscription or access fees, or even contributions from the researchers themselves. There is no need to favor one of these solutions over the others for all disciplines or nations, and no need to stop looking for other, creative alternatives.

Open access to peer-reviewed journal literature is the goal. Self-archiving (I.) and a new generation of open- access journals (II.) are the ways to attain this goal. They are not only direct and effective means to this end, they are within the reach of scholars themselves, immediately, and need not wait on changes brought about by markets or legislation. While we endorse the two strategies just outlined, we also encourage experimentation with further ways to make the transition from the present methods of dissemination to open access. Flexibility, experimentation, and adaptation to local circumstances are the best ways to assure that progress in diverse settings will be rapid, secure, and long-lived.

The Open Society Institute, the foundation network founded by philanthropist George Soros, is committed to providing initial help and funding to realize this goal.

It will use its resources and influence to extend and promote institutional self-archiving, to launch new open-accessjournals, and to help an open-accessjournal system become economically self-sustaining. While the Open Society Institute's commitment and resources are substantial, this initiative is very much in need of other organizations to lend their effort and resources.

We invite governments, universities, libraries, journal editors, publishers, foundations, learned societies, professional associations, and individual scholars who share our vision to join us in the task of removing the barriers to open access and building a future in which research and education in every part of the world are that much more free to flourish.

The BOAI addresses a number of issues that are important and need to be highlighted.

First, it acknowledges that the reason Open Access is now possible is because the Web offers a means for free dissemination of goods. In the days of print-on-paper, free dissemination was not possible because each copy had an identifiable cost associated with it in terms of printing and distribution. Second, and related to the first, the BOAI acknowledges that there are costs to producing the peer- reviewed literature, even though peer review services are provided for free by scientists, as is the raw material, of course.

Third, the BOAI describes two ways in which work can be made Open Access: by self-archiving, that is by depositing copies of papers in Open Access archives (commonly called the 'green route'); and by publishing in Open Access journals, publications that make their content freely available on the Web at the time of publication (referred to as the 'gold route').

Fourth, the BOAI details the kinds of access barriers that are non-permissible in an Open Access world - financial, technical and legal. Implicit in the definition is also the removal of a temporal barrier, meaning that research findings should be immediately available to would-be users once in publishable form, and thereafter available permanently. It is helpful to think of this also in terms of 'price barriers' (for example, subscription costs or pay-per- view charges) and 'permission barriers' (onerous copyright or licensing restrictions on use)10.

Finally, the Initiative addresses the issue of use of the Open Access literature which, it says, should be available to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of these articles, crawl them for indexing, pass them as data to software, or use them for any other lawful purpose. This may seem like an unnecessarily detailed list, but the Initiative was setting in place the conditions needed for digital science in the 21st century, where computational methods will dominate as science becomes more data- intensive and machines need to access the literature to create knowledge. In other words, being able to read an article for free will not be enough.

This has led to an extension of the definition of Open Access, distinguishing between free-to-read and free- to-do more types of access. These are explained in the section below.

1.3.2 Gratis and Libre Open Access

From the viewpoint of policy development, this issue is important. Policies may explicitly acknowledge it, requiring material to be made Open Access with provision for re-use in ways over and above simply reading. This most liberal definition of Open Access has been called, by agreement within the Open Access advocacy community, 'libre' Open

Access. The other variant, where material is free to read but does not explicitly permit further types of re-use, is called 'gratis' Open Access.

The difference between the two may seem subtle, but the implications are rather profound. In terms of scientists' behaviour in respect of their own interests, all scientists want their work to be read and built upon by others. That is precisely why they publish: unless they work in industry or in another private capacity, contributing to the general knowledge base is the purpose of their employment as public servants. Gratis Open Access thus presents no conflict with the normal aims of scientists to make their findings available and to have as much impact as possible. The argument goes that they may not, however, be so clear about the issue of liberal re-use rights for their work. Making their articles available for other scientists to read is one thing, it is said, but allowing more may be a step too far.

It is worth examining here what is implicated. There are two fundamental types of re-use. First, what we might term 'human re-use', by which is meant that scientists may use an article in ways other than just reading it to find out what its messages are. We can imagine a number of possibilities.

A scientist might:

■ extract a component of the article (a graph or table, photograph or list) and carry out further analysis or modification for the purpose of research

■ use one of these components alongside others like it to form a public collection

■ use one or other of those components in presentations or teaching materials that are made widely available

■ use a component in an article for publication

■ extract large chunks of text for use in other articles

But fellow scientists are not the only potential users.

There may be people who could make commercial use of material in the article, too.

Second, there is what we can term 'machine re-use', by which is meant that computers can also use what is in the literature. Computation upon the scientific literature is in its early days, but technologies are being developed and refined because of the huge potential they have for creating new knowledge that can be beneficial18.

For example, text-mining of the biomedical literature19 has the potential to identify avenues to discovering new drugs and other therapies20. It is worth noting that these technologies do not work well on texts in PDF format, which unfortunately is the format that most Open Access articles are available in at the moment. The preferred format is XML (Extensible Markup Language). This may seem a trivial point, but in policy terms it is rather significant. In the future, as this area develops, policies are likely to discourage PDF and insist on a format that is either XML or can be easily converted to it.

1.3.3 Other formal definitions of Open Access

Subsequent definitions of Open Access have been offered. The Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing21

built upon the BOAI by specifying in detail the ways in which Open Access material can be used. In particular, it specifies what an Open Access publication is and which rights the owners or creators of the work grant to users through the attachment of particular licences. It says, an Open Access Publication is one that meets the following two conditions:

1. The author(s) and copyright holder(s) grant(s) to all users a free, irrevocable, worldwide, perpetual right of access to, and a license to copy, use, distribute, transmit and display the work publicly and to make and distribute derivative works, in any digital medium for any responsible purpose, subject to proper attribution of authorship, as well as the right to make small numbers of printed copies for their personal use.

2. A complete version of the work and all supplemental materials, including a copy of the permission as stated above, in a suitable standard electronic format is deposited immediately upon initial publication in at least one online repository that is supported by an academic institution, scholarly society, government agency, or other well-established organization that seeks to enable open access, unrestricted distribution, interoperability, and long-term archiving (for the biomedical sciences, PubMed Central is such a repository).

The Bethesda Statement therefore reinforces the emphasis on barrier-free dissemination of scientific works and expressly details the types of re-use that Open Access permits, including the making of derivative works, and the rights/licensing conditions that apply.

18 For an overview of open computation, see Lynch (2006): full reference in the bibliography.

19 For an explanation of the technologies, see Rodriguez-Esteban (2009): full reference in the bibliography.

20 For an example of how the technologies work, the UK's National Centre for Text Mining (NaCTeM) and the European Bioinformatics Institute are collaborating with UK PubMed Central on text-mining the biomedical literature: http://www.nactem.ac.uk/ukpmc/

21 http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/bethesda.htm

Finally, the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities was

published in 200322. This is essentially the same as the Bethesda Statement but at the third of the annual Berlin Conferences on Open Access (which are held in different cities each year) the conference agreed to an additional recommendation for research institutions, as follows:

In order to implement the Berlin Declaration institutions should implement a policy to:

1. require their researchers to deposit a copy of all their published articles in an open access repository

and

2. encourage their researchers to publish their research articles in open access journals where a suitable journal exists (and provide the support to enable that to happen).

Although there have been further attempts to define Open Access, these three (Budapest, Bethesda and Berlin), usually used together and referred to as the 'BBB definition of Open Access', have become established as the working definition.

This account of the definition of Open Access has been thorough because the issue is critically important to policy development, whether by research funders, institutions or other bodies. It is easy for policies to specify too little - in which case what results is not a true Open Access body of literature; or too much - in which case there are too many hurdles to clear to achieve Open Access satisfactorily.

Reflection on the definitions above makes it clear that there are three main issues to deal with in policy development:

■ what should be covered by a policy

■ what should be specified with regard to timing, costs, and how Open Access should be provided

■ and what conditions should be applied with respect to copyright and licensing

These issues are further discussed in section 8.

1.4 Target content for Open Access

Central to making policy on Open Access is what types of research outputs are to be covered. The general term that is used to describe the target of Open Access is 'the peer- reviewed research literature'. In broadest terms, this would cover journals, peer-reviewed conference proceedings (the primary dissemination route in some disciplines, such as engineering) and books. Using this general term 'literature', though, brings the need for some caveats.

First, there is the issue of how to deal with scholarly books. Journals are simple: scientists write articles for publication in journals and do not expect payment for this. Indeed, their purpose in writing for journals is to gain reputational capital and benefit personally in the currency of academic research - citations. Book authors, however, do sometimes expect a financial reward as well as reputational capital to come to them from writing books. The financial reward is certainly very small in the vast majority of cases, and most authors in the humanities (which is the discipline most affected since books are the primary dissemination tool) acknowledge that their expectations of financial reward are hardly high23, but the fact that the potential for financial payoff exists means that what can be required in policy terms with respect to journal articles cannot be the same for books. Nonetheless, policies usually do mention books (and book chapters), complete with caveat (see section 8 for further discussion on this).

Second, there is another category of research output that is increasingly becoming a focus for policy, and that is research data. Science is now data-intensive and becoming ever more so. In some disciplines (but not all) there is an acknowledged need to share data in order to effect progress. Science is simply too big in some fields to move forward without collaborative intent. The Human Genome Project illustrates this point: thousands of scientists around the world worked on the effort to sequence the whole human DNA complement and the principles of data sharing were agreed at the now-famous Bermuda meeting in 199624. There is excellent provision of public data storage and preservation facilities for scientists in biomedical research25, as there is in some other data- intensive disciplines.

22 http://oa.mpg.de/lang/en-uk/berlin-prozess/berliner-erklarung/

23 Anecdotally, most cheerfully agree that reputational capital far outweighs financial reward as the main hoped-for benefit from publishing their work in book form.

24 1st International Strategy Meeting on Human Genome Sequencing: This included a principle that no-one would claim intellectual property rights over genome data and that data would be made publicly-available within 24 hours of being produced: http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/ Human_Genome/research/bermuda.shtml#1

As well as the significant policy and infrastructure developments to support Open Data seen in some disciplines there is a more general awakening of interest in this topic. Research funders, keen to optimise conditions for scientific progress, are also working on policy support to ensure that research data are made accessible by the scientists they fund. Many research funders around the world now have Open Data policies in place, some of them backed by particular infrastructural arrangements to enable the practicalities of complying with them26. Some researchers use their institution's digital repository for depositing datasets for sharing, or place datasets on open websites. Publishers also make space available on their own websites for datasets supporting journal articles and in some cases journals require data to be made openly available as a condition of publication11. It must be emphasised, however, that data sharing is by no means ubiquitous and data management practices and norms vary considerably from one discipline to another, as many studies have demonstrated12. There is, however, growing organisation and formalisation of this field and the recently-developed Panton Principles define the aims and principles of Open Data concept13.

Third, there are other types of research literature for which openness is considered desirable. These are theses (masters and doctoral) and the 'grey' literature (the research literature not destined for peer-reviewed journals such as working papers, pamphlets, etc). Whilst these are not covered by the formal definition of Open Access, they are second-tier targets and it should be noted that in some disciplines this tier of outputs is of very considerable significance.

Finally, though this is till very much in its infancy, there is a move towards developing an Open Bibliography of science. The premise here is that scientific information would be much more easily findable were there to be a properly constructed, fully-open bibliographic service (currently, the most comprehensive bibliographic services are paid-for services produced by commercial publishing companies). Though this issue is nowhere approaching the stage where policy development can take place, the groundwork is being done to build an Open Bibliography system30.

Summary points on the development of Open Access

► The Web offers new opportunities to build an optimal system for communicating science - a fully linked, fully interoperable, fully- exploitable scientific research database available to all

► Scientists are using these opportunities both to develop Open Access routes for the formal literature and for informal types of communication

► For the growing body of Open Access information, preservation in the long-term is a key issue

► Essential for the acceptance and use of the Open Access literature are new services that provide for the needs of scientists and research managers

► There are already good, workable, proven-in-use definitions of Open Access that can be used to underpin policy

► There is also a distinction made between two types of Open Access - gratis and libre - and this distinction also has policy implications

► Two practical routes to Open Access ('green' and 'gold') have been formally endorsed by the research community

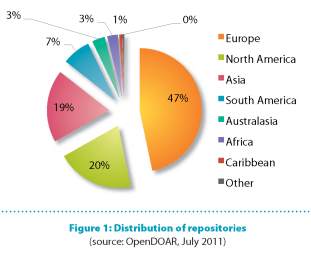

The primary, and original, target for Open Access was the journal literature (including peer-reviewed conference proceedings). Masters and doctoral theses are also welcome additions to this list and the concept is now being widened to include research data and books rather than the whole Web33. The current distribution of repositories is shown in Figure 1.

25 For example, see the databases maintained by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ and the European Bioinformatics Institute: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/

26 As an example, see the Natural Environment Research Council's data centre network in the UK: http://www.nerc.ac.uk/research/sites/data/

27 The journal Nature, for example, has a clause in its conditions of publishing that stipulates that authors must make supporting data available for others to see and use.

28 See: Ruusalepp (2008), Brown & Swan (2009) and Swan & Brown (2008): full references in the bibliography.

29 http://pantonprinciples.org/

30 See the new principles on open metadata promoted by the Joint Information Systems Committee in the UK: http://www.jisc.ac.uk/ news/stories/2011/07/openmetadata.aspx and the Open Knowledge Foundation's Working Group on Open Bibliographic Data http://wiki.okfn. org/Wg/bibliography

SECTION 2.

Approaches to Open

Access

Any form of scientific output can be made openly available, simply by being posted onto a website. This can and does happen for journal articles, book chapters and whole books, datasets of all types (including graphics, photographs, audio and video files) and software. The term Open Access, however, tends to be used about information made available in one of two structured ways.

2.1 Open Access repositories: the 'green' route to Open Access

Open Access repositories house collections of scientific papers and other research outputs and make them available to all on the Web. Because repositories can collect all the outputs from an institution, and because all institutions can build a repository, the potential for capturing high levels of material is excellent, though this potential is only realised if a proper policy is put in place.

31 The most common ones are EPrints (www.eprints.org) and DSpace (http:// www.duraspace.org/)

32 OAI-PMH (Open Archives Initiative - Protocol for Metadata Harvesting):

http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/openarchivesprotocol.html

33 For example, the Bielefeld Academic Search Engine: http://base.ub.uni- bielefeld.de/en/index.php or OAIster: http://oaister.worldcat.org/

Repositories mostly run on open source software31 and all adhere to the same basic set of technical rules32 that govern the way they structure, classify, label and expose their content to Web search engines. Because they all abide by these basic rules they are interoperable: that is, they form a network and, through that network, create between them one large Open Access database, albeit distributed across the world. They are all indexed by Google, Google Scholar and other search engines, so discovering what is in this distributed database is a simple matter of searching by keyword using one of these tools. It can also be done using one of the more specialised discovery tools that index only repository content

2.1.1 Centralised, subject-specific repositories

The earliest type of repository was the subject-specific, centralised type and there are some outstandingly successful examples. One such is the repository for high-energy physics and allied fields, called arXiv (see section 1.2). Subject-specific repositories may be created by authors directly depositing their work into the repository (like arXiv), or by 'harvesting' content from other collections (e.g. university repositories) to create a central service. The economics Open Access repository, RePEc, is created in this way. The success of the 'harvesting' type of repository is dependent upon there being sufficient suitable content in the university or research institute repositories that can be harvested. The success of direct- deposit repositories is dependent either upon community norms where the expectations are that authors will share their findings, or upon policy support that establishes this behaviour where the culture of sharing does not pre-exist. This is therefore an important policy issue, and is discussed further in section 8.

Another successful subject-specific example is PubMed Central (PMC), the repository that houses the Open Access outputs of the National Institutes of Health amongst other things. It was established in the US in the year 2000, with the contents of just two journals. Within two years it covered 55 journals and numbers have been growing steadily to the present day, when it collects the contents of 600 journals as well as manuscripts deposited by authors. The database currently has around 2 million full-text journal articles, though while all are free to access and read, only about 11% fall under the strictest definition of Open Access by being distributed under a licence that permits more liberal re-use (see section 1.3). The general intention in this biomedical sciences field appears to be to build a network of national or regional PMCs to complement and mirror the US-based one. The first international PMC (PMCi) was established in the UK in 2007 by a consortium of other research funders. A Canadian site has been announced, with discussion of additional sites in other regions, including the possibility of transforming the UK site into a European PMC.

2.1.2 Institutional and other broad- scope repositories

In other fields and disciplines there is no centralised service like PMC or arXiv nor, yet, an established set of cultural practices around Open Access. There is, however, a growing network of institutional repositories, plus a handful of central, broad-scope ones such as OpenDepot34 that serve large communities. These repositories complement the centralised, subject-based repositories. Ultimately, a network in which all research-based universities and research institutes have a repository has the potential to provide virtually 100% Open Access for the scholarly literature.

The first institutional repository was built in the School of Electronics & Computer Science at the University of Southampton, United Kingdom, in 200035. The software that it runs on, EPrints36, is open source and after its release other institutions began to build their own repositories to provide Open Access to their research outputs. Growth has been rapid: within a decade there were 1800 repositories in institutions worldwide and the number continues to increase37 as universities and research institutions see the value of the additional visibility and impact a repository provides.

34 OpenDepot is a central, Open Access repository operated by the University of Edinburgh, UK. It offers a deposit location for researchers whose own institution does not yet have a repository and re-directs articles to the home institution repository when one is established: http://opendepot.org/

35 http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/

36 http://www.eprints.org/software/

Research policy in some countries has also encouraged the establishment of repositories. In the UK, for example, the periodic national Research Assessment Exercise (RAE; in future to be called the Research Excellence Framework, REF38) has required universities to gather information about research activities and outputs. Because a repository provides a structure for such an exercise almost all British universities now have institutional repositories, many with formal policies underpinning them. In Australia, a similar national research assessment exercise39 actually required Australian universities to have a repository to collect research articles for submission to the assessment exercise.

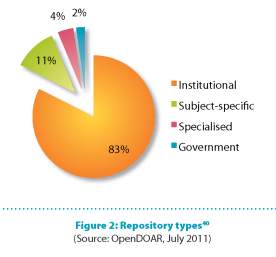

The relative numbers of types of repository are shown in Figure 2.

37 At the time of writing there are well over 2000 repositories globally. Two directories track the numbers and types of repositories: the Directory of Open Access Repositories (ROAR): http://roar.eprints.org/ and OpenDOAR: http://www.opendoar.org/index.html

38 http://www.hefce.ac.uk/research/ref/

39 At the time called the Research Quality Framework (RQF); now called the Excellence in Research for Australia Initiative (ERA) http://www.arc.gov.au/ era/

40 Specialised repositories may collect material on a particular topic from a number of sources, or may focus on one type of content, such as theses

2.2 Open Access journals: the 'gold' route to Open Access

2.2.1 The Open Access publishing arena

Open Access journals also contribute to the corpus of openly available literature. There are around 7,000 of these at the moment, altogether offering over 600,000 articles41. Again, community norms play a role in determining whether such journals are welcomed and supported by researchers. In some disciplines there are many, highly successful Open Access journals, such as in biomedicine; and in some geographical communities there is also an organised approach to Open Access publishing, exemplified by the Latin American service SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online)42. The potential for capturing high levels of Open Access material by this route is good, but is limited by the willingness of publishers to forego their subscription-based revenue model and switch to one that delivers Open Access (see section 5 for a discussion of business models).

The Open Access publishing scene is very varied: there are some large publishing operations and thousands of small or one-journal operations. And just as for the subscription- access literature, quality ranges from excellent to poor.

The Open Access journal literature is no different in that respect.

The earliest sizeable Open Access publisher to show that Open Access can be consistent with commercial aims was BioMed Central43 (now part of the Springer science publishing organisation). BioMed Central currently publishes some 210 journals, mainly in biomedicine, though also with some coverage of chemistry, physics and mathematics. BioMed Central deposits all its journal articles in PMC at the time of publication as well as hosting them on its own website. The Hindawi Publishing Corporation44, the Open Access publisher with the largest journal list, also publishes in the sciences. It has more than 300 journals covering the natural and applied sciences, agriculture and medicine.

41 The Directory of Open Access Journals maintains a list and a search facility: http://www.doaj.org

42 SciELO is an electronic publishing cooperative that offers a collection of Latin American and Caribbean journals and associated services: http:// www.scielo.org/php/index.php?lang=en

43 http://www.biomedcentral.com/

Another publisher, the Public Library of Science45, publishes some of the highest impact journals in biology and medicine (PLoS Biology and PLoS Medicine, plus others). This publisher has also changed the shape of scientific publishing through the launch of PLoS ONE, a journal that covers all the natural sciences. PLoS ONE introduced a new system of quality control. Though still based upon peer review, pre-publication referees are asked to judge an article purely on the basis of whether the work has been carried out in a sound scientific manner. The paper is then published and judgments about its relevance, significance and impact are made through post-publication community response online. The model has proved very successful and has recently been emulated by the Nature Publishing Group with the launch of Nature Scientific Reports46

There has been significant activity in this area in developing and emerging countries, too. Open Access provides the means for scientists in these regions to at last make their work easily findable and readable by developed-world scientists. In scientific communication terms, Open Access is becoming a great leveller. SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), a collection of peer- reviewed Open Access journals published mainly from South American countries in Spanish or Portuguese, covers over 800 journals offering over 300,000 articles in the natural sciences, medicine, agriculture and social sciences. And Bioline International47, a service that provides a free electronic publishing platform for small publishers wishing to publish Open Access journals in the biosciences, has over 50 journals in its collection, all from developing and emerging countries, covering biomedicine and agriculture. As well as these services, libraries generally include the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) in their catalogues, thereby increasing visibility or articles from developing countries and bringing them to the attention of developed world researchers.

2.2.2 'Hybrid' Open Access

As well as the 'pure gold' Open Access journals described above - journals in which all content is Open Access and licensed accordingly - there is another model. Most large scholarly publishers have introduced this in order to offer Open Access while retaining their current subscription- based business model. This so-called 'hybrid' Open Access option allows authors to opt to pay a publication fee and have their article made Open Access within an otherwise subscription journal. Take-up on these options is not high (less than 3% currently), largely because of the level of fee48 but also because many universities and funders who permit authors to use their funds to pay for Open Access publishing will not allow them to do so to publishers who 'double dip': that is, charge an article-processing fee for making an article Open Access but do not lower their subscription charges in line with the new revenue stream. That said, there are a number of publishers who have made public commitments to adjusting the subscription price of their journals as revenue comes in from Open Access charges.

46 http://www.nature.com/srep/marketing/index.html

It should also be noted that many journals offering this option do not make the articles available under a suitable licence: this means that though the articles are free to access and read they are often not allowed to be re-used in other ways, including by computing technologies.

2.2.3 Other ways of making research outputs open

It is possible to make articles and data open by posting them on publicly available websites such as research group site, departmental websites or authors' personal sites. As well as these examples, there is growing interest in community websites49, and researchers are increasingly using these to share articles and other information.

48 For example, fees for 'hybrid' journals published by Wiley and Elsevier are around USD 3000, excluding taxes and colour charges.

49 Such as Mendeley http://www.mendeley.com or Academia.edu http:// academia.edu/

Although these methods do make papers publicly available, these sites lack the structured metadata (labelling system) that repositories or Open Access journals create for each item, and most do not comply with the internationally-agreed standard OAI-PMH protocol (see section 2.1). This means that their contents are not necessarily fully indexed by Web search engines, which means that their visibility and discoverability are compromised. Author websites are also commonly out of date or become obsolete when researchers move from one institution to another, and they play no reliable preservation role. Moreover, one of the significant reasons from the institution or funder viewpoint for having material in a repository is to create a body of outputs that can be measured, analysed and assessed. If a repository is to be used for this purpose then it is important that it collects all the institution's outputs, rather than having

them spread across multiple academic community websites.

Summary points on approaches to Open Access

► There is already considerable infrastructure in place to enable Open Access

► In some disciplines this is much further advanced than others

► In some disciplines cultural norms have changed to support Open Access but not so much in others

► Open Access journals, the 'gold' route to Open Access, are a particularly successful model in some disciplines, and especially in some geographical communities

► The 'green' route, via repositories can capture more material, faster, if the right policies are put in place

► 'Hybrid' Open Access is offered by many publishers.

Predominantly these publishers are 'double-dipping'

SECTION 3.

The Importance of Open Access

The importance of access to research in the context of building a sustainable global future has been highlighted by UNESCO previously, and data have been produced on the patterns and trends with respect to the generation of, and access to, scientific information50.

3.1 Access problems

Probably no scientist, wherever they may live and work, would claim that he or she has access to all the information they need. Many studies have shown that this is so even in wealthy research-intensive countries. The Research Information Network (RIN) in the UK, concluded in a meta-report that brought together the findings from five RIN-sponsored studies carried out on discovery and access51, that 'the key finding is that access is still a major concern for researchers'

On a global scale, the SOAP study, a large, 3-year, publisher-led, EU-funded project looking at Open Access and publishing, surveyed 40,000 researchers across the world and found that 37% of respondents said they could find all the articles they need 'only rarely or with difficulty' This presumably even takes into account the workarounds that researchers use - emailing authors, asking colleagues in other institutions, or using paid-for access through ILL (inter-library loan) or PPV (pay-per-view) systems.

Inter-library loan expenditure on journal articles is another indicator of lack of access. The UK's 'Elite 5' universities, those with libraries expected to be the best-resourced in the country, show inter-library loan costs for journal articles currently averaging around USD 50,000 per year. And Open Access repository download figures indicate the extent that access is being fulfilled through that Open Access route for those who are unable to access the original journal52.

We may also assume that journal access problems in the developed world will increase. Library budgets are under pressure, Big Deals (purchase of 'bundles' of a publisher's offerings on 2-, 3- or 5-year deals) are being cancelled53 and society-published journals are feeling the chill wind of recession in the form of attrition of prestigious but unaffordable titles.

50 Reported in the UNESCO Science Report 2010 and the World Social Science Report 2010: see UNESCO (2010) and International Social Science Council (2010) in bibliography for full reference

51 http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/using-and-accessing-information-resources/ overcoming-barriers-access-research-information

In the developing world, the situation is even more serious. A World Health Organization survey carried out in the year 2000 found that researchers in developing countries claim access to subscription-based journals to be one of their most pressing problems. This survey found that in countries where the per capita income is less than USD 1000 per annum, 56% of research institutions had no current subscriptions to international journals, nor had for the previous 5 years (Aronson, 2004).