The SAFE Project

This guide was financially supported by the European Commission Directorate General for Health and Consumer Protection, as part of 'The SAFE Project: A European partnership to promote the sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people.' The project is a partnership between IPPF European Network, WHO Regional Office for Europe and Lund University. It aims to build on existing research in the field, to provide an overall picture of the patterns and trends across the region, to develop new and innovative ways to reach young people with SRHR information and services, and to inform, support and advance policy development.

This publication was researched and written by Kay Wellings and Rachel Parker of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK.

Annette Britton from IPPF European Network was responsible for the overall coordination of the publication.

IPPF European Network

IPPF is the strongest global voice safeguarding sexual and reproductive health and rights for people everywhere. The IPPF European Network is one of IPPF's six regions. IPPF European Network increases support for and access to sexual and reproductive health services and rights in 41 member associations throughout Europe and Central Asia.

IPPF European Network Rue Royale, 146 1000 Brussels Belgium

Tel: +32 2 250 0950 Fax: +32 2 250 0969 Email: info@ippfen.org www.ippfen.org

© 2006 IPPF European Network

Editor: Wendy Knerr

Design: S0rine Hoffman (front cover), Page In Extremis (inside pages)

Table of Contents

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

|

Foreword..................................................................... |

................................3 |

|

Acknowledgements........................................................... |

................................4 |

|

Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................. |

................................5 |

|

Introduction .................................................................. |

................................7 |

|

Overview ..................................................................... |

...............................11 |

|

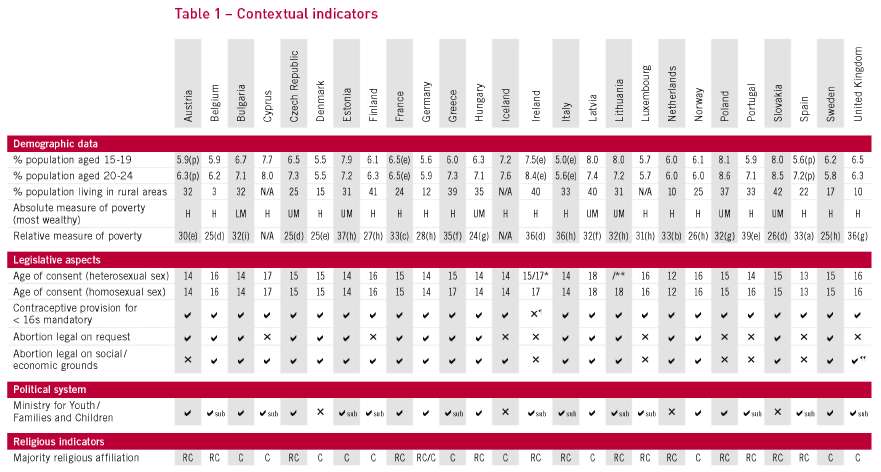

Table 1 - Contextual indicators ........................................... |

...............................18 |

|

Table 2 - Implementation-related indicators .............................. |

...............................20 |

|

Table 3 - Indicators of outcome........................................... |

...............................22 |

|

Country Reports.............................................................. |

...............................25 |

|

Austria.................................................................... |

...............................26 |

|

Belgium................................................................... |

...............................28 |

|

Bulgaria................................................................... |

...............................31 |

|

Cyprus.................................................................... |

...............................33 |

|

Czech Republic............................................................ |

...............................35 |

|

Denmark.................................................................. |

...............................37 |

|

Estonia.................................................................... |

...............................39 |

|

Finland.................................................................... |

...............................41 |

|

France.................................................................... |

...............................44 |

|

Germany.................................................................. |

...............................45 |

|

Greece .................................................................... |

...............................48 |

|

Hungary................................................................... |

...............................50 |

|

Iceland.................................................................... |

...............................53 |

|

Ireland.................................................................... |

...............................55 |

|

Italy ...................................................................... |

...............................58 |

|

Latvia .................................................................... |

...............................60 |

|

Lithuania ................................................................. |

...............................62 |

|

Luxembourg .............................................................. |

...............................64 |

|

The Netherlands .......................................................... |

...............................66 |

|

Norway ................................................................... |

...............................69 |

|

Poland.................................................................... |

...............................71 |

|

Portugal .................................................................. |

...............................73 |

|

Slovakia .................................................................. |

...............................75 |

|

Spain ..................................................................... |

...............................77 |

|

Sweden ................................................................... |

...............................79 |

|

United Kingdom .......................................................... |

...............................81 |

|

References................................................................... |

...............................85 |

|

Endnotes................................................................... |

...............................89 |

|

Annex: Questionnaire ........................................................ |

...............................91 |

2

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

This guide was created to assist policymakers and governments to develop better policies and practices related to sexuality education. Additionally it is intended to help EU Member States to improve the exchange of information and best practices on adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights and sexuality education.

The guide provides information about sexuality education in 26 European countries, and reflects the reality that policies and practices related to young people's sexual and reproductive health and rights - including sexuality education - vary from country to country. There are, however, similarities in the way many governments approach sexuality education, and in the challenges they face in implementing policies related to this topic. By providing information about the policies for, and challenges to, providing comprehensive sexuality education in diverse cultural, social and political settings, this guide can be a helpful resource for policymakers.

The guide is a component of the 'SAFE Project: A European partnership to promote the sexual and reproductive health and rights of youth', which involves IPPF European Network Regional Office and 26 Member Associations, along with Lund University and the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. IPPF European Network is the lead implementing organization for this three-year project, which started in 2005 and aims to develop new and innovative ways to reach young people with sexual and reproductive health and rights information and services, and to inform, support and advance policy development.

Young people need accurate information, skills and access to youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services if they are to make healthy, informed choices. Comprehensive sexuality education is one of the most important tools we have to ensure that young people have the information they need. This guide is a tool for those working to ensure that policies in Europe support the sexual and reproductive health and rights of young people.

Vicky Claeys

IPPF European Network Regional Director

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

3

IPPF European Network, WHO Regional Office for Europe and Lund University are very grateful to the numerous people who have been involved in putting together this guide to Sexuality Education policies and practices across Europe.

The guide was primarily researched and written by Rachael Parker and Kaye Wellings from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Both of them have worked tirelessly to pull together all the information and to present it in a useful format. Our thanks also to Wendy Knerr who edited the guide and incorporated additional research, feedback and suggestions.

Much of the document is based on the information provided by IPPF European Network Member Associations in the 26 countries covered by the guide. These are non profit organizations working at the national level to ensure the sexual and reproductive health and rights of women, men and young people are met with adequate programmes, policies and resources. In particular, we would like to thank the following:

Elisabeth Pracht from Osterreichische Gesellschaft fur Familienplanung (OGF) in Austria Pascale Maquestiau from the Federation Laique de Centres de Planning Familial (FLCPF) and Telidja KlaT and Dirk Pyck from Sensoa in Belgium Radosveta Stamenkova from the Bulgarian Family Planning and Sexual Health Association (BFPA) Despo Hadjiloizou and Margarita Kapsou from Family Planning Association of Cyprus (FPAC) Ruzena Prihodova and Zuzana Prouzova from Spolecnost pro planovani rodiny a sexualnf vychovu (SPRSV) in the Czech Republic Bjarne Christensen and Robert Holm Jensen from Foreningen Sex & Samfund in Denmark Maili Haavandi and Tiia Pertel from the Estonian Sexual Health Association (ESTL) Osmo Kontula from Vaestoliitto in Finland Dominique Audouze and Maite Albagly from Mouvement Francais pour le Planning Familial (MFPF) in France Alexandra Ommert, Elke Thoss and Sigrid Weiser from PRO FAMILIA Bundesverband in Germany Stavros Voskakis from the Family Planning Association of Greece (FPAG) Eva Barko from Magyar Csalad- es Novedelmi Tudomanyos Tarsasag in Hungary Soley Bender from Fraedslusamtok urn kynlff og barneignir (FKB) in Iceland Karen Griffin and Natalie McDonnell from the Irish Family Planning Association (IFPA) Eleonora Curto from the Unione Italiana dei Centri di Educazione Matrimoniale e Prematrimoniale (UICEMP) in Italy Anda Vaisla and Iveta Kelle from Latvijas Gimenes Planosanas un Seksualas Veselibas Asociacija "Papardes Zieds" (LAFPSH) in Latvia Esmeralda Kuliesyte from Seimos Planavimo ir Seksualines Sveikatos Asociacija(FPSHA) in Lithuania Catherine Chery from the Mouvement Luxembourgeois pour le Planning Familial et I'Education Sexuelle (MLPFES) in Luxembourg Barbara van Ginneken and Laura van Lee from Rutgers Nisso Groep in the Netherlands Lisbet Nortvedt from Norsk forening for seksuell og reproduktiv helse og rettigheter (NSRR) in Norway Piotr Kalbarczyk from Towarzystwo Rozwoju Rodziny (TRR) in Poland Duarte Vilar and Ana Calado Inacio from Associacao Para o Planeamento da Famflia (APF) in Portugal Olga Pietruchova from Slovenska spolocnost pre planovane rodicovstvo a vychovu k rodicovstvu (SSPRVR) in Slovakia Marfa Vazquez, Eva Caba, Alba Varela and Justa Montero from the Federacion de Planificacion Familiar de Espaha (FPFE) in Spain Hans Olsson from Riksforbundet for Sexuell Upplysning (RFSU) in Sweden and Margaret McGovern from fpa in the United Kingdom.

We are also grateful to Maija Ritamo, Elise Kosunen and Arja Liinamo from Finland, George Creatsas from Greece and Sigurlaug Hauksdottir from Iceland, for reviewing their respective country reports. Thanks also to Evert Ketting, Tim Shand and Doortje Braeken for their overall feedback and suggestions.

IPPF European Network was responsible for coordinating the development of the guide. We would like to thank our colleagues in the WHO Regional Office for Europe and Lund University for their continuous support throughout, particularly Gunta Lazdane, Jerker Liljestrand and Jeffrey Lazarus, whose assistance was invaluable.

4

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

5

6

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

7

All young people have the right to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health information, education and services, to be active citizens, to have pleasure and confidence in their sexuality, and to be able to make their own informed choices. IPPF EN and WHO regional guidelines both promote this belief.

In order to meet these rights, we seek to promote a model of sexuality education that considers the various inter-related dynamics that influence sexual choices and the resulting emotional, mental, physical and social impacts on each person's development. This positive approach to sexuality education includes an emphasis on sexual expression and sexual fulfilment, representing a shift away from methodologies that focus exclusively on the reproductive aspects of adolescent sexuality. In addition, this approach recognises that both sexually active and sexually abstinent youth need information to be able to make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive lives. Through encompassing these issues, a comprehensive approach to sexuality education therefore contributes to addressing not only the health and wellbeing of young people, but also their sexual and reproductive rights.

The purpose of this guide

This sexuality education reference guide aims to systematically and coherently bring together information on sexuality education policies and programmes across Europe. As such, it is hoped that it will be a useful tool for both professionals and policy makers working in the field of young people's sexual and reproductive health and rights, and that it will enable them to make well founded arguments for comprehensive sexuality education in schools, and to refer quickly to what's happening and what's working in other European countries.

How the guide is organised

The guide is divided into three broad sections. The first section gives an overview of the situation in Europe, and analyses the similarities and differences that various countries have experienced in delivering sexuality education, the factors hindering and enhancing provision, and evidence for the effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality education. This section is followed by three tables which describe the situation in Europe in more quantitative terms, and that can be used to give at a glance data and comparisons between countries. The final section contains individual country reports that describe in more detail the situation with regards to sexuality education in each of the 26 countries covered.

Design and method

To prepare this guide, a common template was prepared (see appendix) which aimed to seek, wherever possible, comparable information for each country, and to present information under standard headings. This was then sent to the IPPF European Network (IPPF EN) Member Association (MA)1 contact in each of the 26 countries covered by the project. The MAs were asked to complete the template and also to provide contact details of other people within their country whom they thought would be able to provide additional information. These additional contacts were then sent the template and were asked, where appropriate, for specific information dependent on their area of expertise. In some cases the MA consulted their contacts prior to returning the template and so the initial response was comprehensive.

1 Member Associations (MAs) are IPPF European Network members. They are non-profit organizations providing information, training, education and health services in the areas of sexual and reproductive health and rights in their own countries.

8

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

The information collected from the templates was then presented in tabular form (Tables 1 and 2), and was also used as the basis for the individual country reports. Any gaps in the information provided were filled, where possible, using published literature, policy documents and international comparisons, of the kind produced by UNICEF, the Alan Guttmacher Institute, SIECUS and IPPF. Routine data was also collected from sources such as Eurostat, WHO, World Bank and EuroHIV and was used to complete tables 1 and 3. All draft tables and reports were sent to the MAs for verification, and any necessary amendments made.

What is the scope of the guide?

In terms of the subject area, it should be noted that this guide is by no means comprehensive and that it does not cover out of school sexuality education in any detail. There are certain limitations with the methodology employed to compile the guide, and users should exercise caution in comparing data from individual countries.

Definition of sexuality education

Across Europe different terms are used to refer to sexuality education, varying from 'family life education' through to life skills education' and 'sex and relationships education'. A detailed analysis of the different terminology used, and the various perspectives that are reflected by these terms, is included in Section 2 of this guide, under 'Curriculum Content'.

However, for consistency the term 'sexuality education' has been used throughout this guide. This term is used to refer to a comprehensive, rights based approach to sexuality education, which seeks to equip young people with not only the essential knowledge, but also the skills, attitudes and values they need in order to determine and enjoy their sexuality, both physically and emotionally, and individually as well as in relationships. This approach is summarised in the following table:

Sexuality Education must help young people to:

Acquire accurate information

On sexual and reproductive rights; information to dispel myths; references to resources and services

Develop life skills

Such as critical thinking, communication and negotiation skills, self-development skills, decision making skills; sense of self; confidence; assertiveness; ability to take responsibility; ability to ask questions and seek help; empathy

Nurture positive attitudes and values

Open-mindedness; respect for self and others; positive self-worth/esteem; comfort; non-judgmental attitude; sense of responsibility; positive attitude toward their sexual and reproductive health

Sexuality education covers a broad range of issues relating to both the physical and biological aspects of sexuality, and the emotional and social aspects. It recognizes and accepts all people as sexual beings and is concerned with more than just the prevention of disease or pregnancy. CSE programmes should be adapted to the age and stage of development of the target group.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

9

Links to other IPPF resources

This guide is aimed to complement the policy framework and guidelines on young people's sexual and reproductive health and rights, which contains specific recommendations for policy and decision makers at the national level on sexuality education, as well as on other sexual and reproductive health issues.

At the international level, IPPF has developed a Framework for Comprehensive Sexuality Education, which is based on extensive consultations. This document lays out IPPF's current thinking on what constitutes the important elements of sexuality education, which include: gender; sexual and reproductive health; sexual citizenship; pleasure; violence; diversity; and relationships2.

In addition, IPPF is currently working to develop guidelines and standards on comprehensive sexuality education, in partnership with young people, the Population Council, and other expert organisations. The primary aim is to set minimum standards for sexuality education, which are based on a positive approach that links safer sex with positive development, empowerment and choice, rather than the traditional approach that links sex with risk taking and the prevention of pregnancy and infections.

For a copy of the IPPF Framework of Comprehensive Sexuality Education see: http://content.ippf.org/output/ORG/files/13582.pdf

10

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

11

A broad, historical overview of sexuality education in European countries reveals a wide variety of methods and policies that have shaped provision.

Yet despite the social, cultural, political, and economic differences among countries, there are similarities, both in provision and in how different countries have addressed obstacles and opposition to sexuality education. Each country's unique experience adds something to the debate about how best to provide sexuality education, and how advocates can ensure that young people are able to exercise their right to sexuality education. By comparing country and cultural characteristics, the ease with which sexuality education can be implemented, and at what age and in what form it is available, advocates can learn valuable lessons for campaigning for or strengthening sexuality education.

This section summarizes the findings related to delivering sexuality education in Europe, the factors hindering and enhancing provision, and evidence for the effectiveness of comprehensive sexuality education.

How is sexuality education delivered?

Curriculum content

The content of sexuality education varies greatly within, as well as between, countries. In many cases, it is difficult to get a clear picture of what is included in each country. To shed light on this, it is helpful to look at the area of the curriculum in which sexuality education is taught, how it is labelled, and the agencies responsible for its provision.

Cross-curricular teaching

Sexuality education should, many believe, be integrated across all school subjects and at all grades. Yet it is still rare for sexuality education in Europe to be covered across the curriculum (except in Primary School). However, there are exceptions. For example, in Portugal sexuality education is taught by teachers of Biology, Religious Education, Geography and Philosophy.

Focus on biology

Typically, sexuality education is taught in Biology lessons, and in perhaps one other area of curriculum. In Belgium, biological aspects are covered in Biology lessons, and moral and ethical aspects in Religious and moral philosophy lessons. In the Netherlands, the additional curriculum subject is Society; in Denmark, Danish lessons, and in Estonia, Human Studies. In France, sexuality education is mainly incorporated within Health Education but occasionally in Citizenship, reflecting a broader vision of sexuality education. The widespread pattern of timetabling sexuality education in Biology lessons reflects a fairly pervasive emphasis on health-related aspects of the subject, and a weaker focus on personal relationships.

Rarer focus on relationships

The inclusion of the term 'relationship' in the names of sexuality education curricula in many countries (e.g. in Belgium sexuality education is called 'Relationship and Sexuality Education', and in Cyprus 'Relational and Sexual Education') signals that the content goes beyond a simple mechanistic coverage of biological facts, and includes an emphasis on psychosocial aspects of the subject. Research has shown that pupils welcome this and are critical of curricula in which too much emphasis is placed on the biological aspects of sex and reproduction. What is needed is more guidance on the emotional and social aspects of sexual relationships.

12

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

Ideological perspectives

Terms used for sexuality education may reflect national ideologies. In some countries of Eastern Europe (Slovakia, Poland and Hungary, for example), adoption of the term 'Family Life Education' reflects an emphasis on social structure. In other former Eastern bloc countries, and in Belgium, 'gender' enters the description.

Trends in thinking

Changes in the labelling of sexuality education also reveal shifts in thinking over time. In Portugal, for example, concern about HIV and AIDS coincided with the renaming of the 'Programme for Personal Development' in the 1990s to become 'Programme for Health Education'.

Methods used

A wide variety of teaching methods is in evidence throughout Europe, from traditional formal classroom teaching to peer education, and from conventional visual and mass media, to games, videos, CD-ROMS and theatre. Increasingly, the Internet is being used for educational purposes in some countries. Nevertheless, a didactic approach to sexuality education remains common, despite pupils' preference for interactive methods (Ogden and Harden, 1999) (Milburn, 1995) (Macdowall et al, 2006).

Agencies responsible for provision

The most common pattern across European countries is for school teachers themselves to provide sexuality education. The evidence is that the recruitment of carefully selected and trained implementers is essential to the success of sexuality education programmes and this is by no means universal across the European countries.

Involvement of health professionals

Doctors, school nurses and other health professionals are rarely involved in providing sexuality education. This may be a good thing in that it helps to avoid over-medicalization of the topic. But a case can be made for a wider role for health professionals in terms of recognizing problems among young people, such as indications of physical or sexual abuse, pregnancy or STIs.

Pupil visits to health settings

Visits to health settings outside of schools is not common, despite evidence that sexuality education is more effective when it involves links with local sexual health services (Health Development Agency, 2001).

Peer-led sexuality education

These techniques are not greatly in evidence and do not appear to be used at all in some countries (e.g., France).

Involvement of NGOs

Voluntary and non-governmental organizations feature prominently among agencies that are brought into schools to teach sexuality education. They provide sexual health seminars, coordinate peer-education networks, organize public education campaigns and provide counselling services. NGO involvement in providing sexuality education has advantages in that it allows statutory agencies to distance themselves from the subject. Even in Central and Eastern European countries, where civil society has emerged and been able to work openly only recently, NGOs contribute - if not by teaching, then by providing sexuality education resources to educators and the general public. Central and Eastern European countries are gaining ground fast and there is good evidence of training for relevant staff.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

13

Choice of national agency

The government ministry or department that a country chooses to address sexuality education is a reflection of its approach to the topic. In France, the Ministries for Public Health and for Public Education are involved. In Greece, policy is determined by the Ministries of both Education and Health Education. On the whole, the Ministry of Education is the government department most commonly involved (e.g., in the Czech Republic, Estonia, Iceland, Finland, Latvia, and Ireland), generally with involvement from another department (e.g., Youth and Sports in the Czech Republic, Social Affairs and Health in Finland). Where sexuality education is more broadly conceived, several ministries are involved. In Belgium, these include the Ministries of Welfare, Education and Youth. In the Netherlands, policy development is carried out in the Ministry of Public Health, Welfare and Sports, together with involvement from the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Social and Foreign Affairs.

How adequate is provision?

The quality and frequency of provision of sexuality education varies not only between countries, but also within them and from school to school, and it is difficult to assess overall adequacy. Very few countries have formal evaluation processes, and the assessment of the effectiveness of sexuality education is largely drawn from academic studies of specific projects. The following factors influence the adequacy of provision.

Area of the country

Urban/rural differences appear to have a substantial impact on the provision of sexuality education. In more sparsely populated countries (such as Greece) there are signs that facilities are concentrated in large urban areas. More commonly, though, differences seem instead to focus on religious variation. In what was reported as the 'bible belt' of the Netherlands, for example, there are strong religious convictions among the public and policy makers, and sexuality education in schools encounters local opposition. Moreover, in Poland religious and cultural pressures are causing an uneven distribution of sexuality education.

Needs relating to diversity

The growth of immigrant populations, for example in France, Germany and the Netherlands, provided the impetus for increased efforts to address issues around cultural diversity in sexuality education.

Which factors hinder and enhance provision and how can they be addressed?

Cross-national comparisons reveal common factors influencing the relative ease of implementation of sexuality education. To varying degrees, the subject is controversial virtually everywhere. Thus, there is considerable scope for sharing lessons learned from one European country with another, particularly with regard to the following factors.

Reconciling political and religious views

Very few countries exhibit complete acceptance of sexuality education across all groups, and political context exerts a strong influence on implementation. In countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark, sexuality education is widely accepted and supported, while in other countries there is still strong opposition and a

14

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

lack of support. Even in the Netherlands, anti-choice groups and individuals are vocal in their opposition. In predominantly Catholic countries such as Ireland, objections are forcefully made and extend to the provision of sexual health services as well as education. The collapse of communism in some Central and Eastern European countries, such as Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, created conditions for the revival of Catholic interest. While in Germany, persistent Roman Catholic-inspired anti-choice opposition creates a difficult climate in which to implement sexuality education curricula. And in several countries, there is evidence that Muslim faith groups oppose sexuality education as it is currently provided. Much has been achieved in actively involving religious organizations in sexuality education in partnership. In Portugal, for example, NGOs involved include the Pro-Life Movement; in Ireland, a Catholic marriage support agency is used to deliver aspects of the Relationship and Sexuality Education (RSE)/ Social Personal and Health Education (SPHE) programme; in Greece, the church is involved in implementing sexuality education, as well as curriculum implementation (including enlisting support from appropriate authorities).

The need for media advocacy

The stance taken by the media varies greatly across countries. In some (mainly Scandinavian) countries, the media are largely supportive and informative on sexual matters, and treat sexuality positively. In Denmark, national broadcasting companies have freely donated air time to sexuality education. In other countries, such as the UK, sexual issues (particularly those related to young people), are treated more sensationally (particularly by the print media) with adverse effects on sexuality education. A more pro-active stance is needed by those involved in policy and provision of sexuality education to engage with the media in conveying the need for, and the positive impact of, sexuality education on the well-being and health of young people.

Need for greater synergy and 'joint action'

Throughout Europe, there have been many sexual health campaigns using the mass media, including unprecedented efforts in HIV and AIDS public education since the mid-1980s. Yet there are few instances of synergy between public education campaigns and school sexuality education. This may be because the campaigns are generally carried out at national level, by advertising agencies in collaboration with health educational agencies and Ministries of Health. There are advantages for sexuality education in terms of increased collaboration across these agencies. Drawing on the messages of media campaigns (both those that use donated media time or space, and those that are paid for) for use in classroom-based sexuality education lessons would be an effective way of disseminating a common message that can be reinforced in various settings.

Positive effects of negative publicity

Some government agencies have shown apprehension and in some cases outright anxiety about information provided in sexuality education materials, which has often resulted in censorship and subsequent media attention. For example, in England in the late 1980s, a sexuality education manual was partially shredded because of disagreement between the Departments of Health and Education over explicit references to condom use among young people under the age of sexual consent. Similar examples were documented in Italy in the 1990s, and in Denmark, in 2004. Evidence shows, however, that where there is a robust defence of sexuality education interventions or materials, there can be positive outcomes. For example in Spain, the 'Pontelo, Ponselo' campaign and its associated sexuality education programme, led to a national furore when church leaders and others openly criticized the programmes focus on condom use. This led to greater public awareness and more open discussion about sexuality education than might otherwise have been possible without the publicity.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

15

Crisis intervention

Media attention on adverse sexual health issues and trends has sometimes helped to prioritize sexual health on the public agenda. The most striking example of this was the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the recognition of which led to changes and advancements in sexuality education in many countries. In Ireland and in France, for example, fear of the epidemic raised awareness of the need for sexuality education and prompted considerable discussion and activity around sexuality education. Agencies that deal with sexual health and education were set up or strengthened, and there was increased development of expertise in the area. This is good news, but now the challenge is to maintain this impetus and continue the advancement of sexuality education.

Sharing expertise

IPPF European Network Member Associations-many of which are the primary actors in the field of sexuality education in their respective countries -successfully share their expertise with each other. There has been collaboration between Central and Eastern European Member Associations and those from other European countries that have particular experience in implementing and advocating for comprehensive sexuality education. For example, the Member Associations in the Netherlands and Denmark have helped other Member Associations to develop comprehensive sexuality education programmes or policies. And the Estonian Member Association has cooperated closely with Denmark's Foreningen Sex & Samfund, and the Member Associations in Finland, Norway and Sweden.

These are just two examples of successful sharing of expertise across the European Network.

Using and influencing national regulations and guidelines

Sexuality education is not yet mandatory in every European country, and this is problematic for both policy and practice. In countries in which it is mandatory (e.g., the Netherlands, Norway, Estonia, Finland and Hungary) implementation is supported because these efforts are sanctioned at national level. Where this is not the case, national regulations governing sexuality education

- evidence-based and drawing on best practice

- can clearly help providers in making the case for sexuality education.

Sustaining sexuality education programmes

There is evidence of a reduction in national commitments to providing comprehensive sexuality education, particularly in countries where there is clear evidence that sexuality education has been effective in lowering rates of teenage pregnancy and STIs. In the Netherlands, for example, the success of its comprehensive sexuality education curricula may now be threatening its existence: awareness that teenage conception rates are lower than in other countries has contributed to the partial withdrawal of funding and dismantling of agencies that provide sexuality education, and recent signs are that teenage pregnancy rates are increasing. In Denmark, by contrast, where efforts to improve services and education for young people have been sustained, rates of teenage pregnancy have not increased. A favourable climate is necessary, but not sufficient, for sexuality education programmes to be effective. As these examples indicate, past success will not guarantee continued progress.

16

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

What evidence is there that school sexuality education is effective?

There has been a good deal of debate about the benefits of sexuality education. Some people claim that sexuality education enables young people to make informed choices about sexual relationships and to protect their sexual health. Others disagree, claiming that sexuality education may have harmful effects by, for example, hastening the onset of sexual activity. Until recently this debate took place in the absence of reliable evidence to support either view. This review of sexuality education in European countries has shown that systematic evaluation of programmes is all too rare. However, there is now strong international evidence that school-based sexuality education can be effective in reducing sexual risk behaviour and is not associated with increased sexual activity or increase sexual risk taking, as some have feared (Kirby, Laris and Rolleri, 2005). On the contrary, the majority of sexuality programmes reviewed either delayed sex or reduced the numbers of sexual partners among young people. This same review found that sexuality education has a positive effect on knowledge and awareness of risk, values and attitudes, efficacy to negotiate sex and to use condoms, and communication with partners and parents - all of which have been shown to lead to healthy behaviour.

In analyzing data on behaviour and provision of sexuality education across different European countries, this research project has found no evidence of a link between provision of sexuality education and premature sexual behaviour. Sexuality education programmes should not be seen in isolation, but as important components in broader initiatives to improve the health and well-being of young people.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

17

* Age of consent in Ireland 15 (male) 17 (female) ** Lithuania has no legal age of consent

11 providers can prescribe contraceptives but are not obliged to n not Northern Ireland

Explanatory notes

% population aged 15-19; % population aged 20-24

2004 figures for all countries except Greece and Estonia which are for 2003; (e) - estimated value, (p) - provisional value

% population living in rural areas

Rural population calculated as total minus urban population - figures are for 2002

Absolute measure of poverty

Economies are divided among income groups according to 2001 Gross National Income (GNI) per capita; H - High, UM - Upper middle, LM - Lower middle, L - Lower

Relative measure of poverty

Figures represent the Gini index score which measures the extent to which distribution of income (or consumption expenditure) among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. Gini index of 0 represents complete equality; index of 100 implies complete inequality. Survey year: A - 1990, B - 1994, C - 1995, D - 1996, E - 1997, F - 1998, G - 1999, H - 2000, I - 2001

Age of Consent

Where age range varied with region within a country, the lowest age has been used

Ministry for Youth/Families and Children

- Ministry specifically designated to include interest of youth/children

sub - Ministry with sub-division or unit specifically designated to include interest of youth/children x - No Ministry, or sub-division thereof, specifically designated to include interest of youth/children

Majority religious affiliation RC - Roman Catholic C-Other Christian

Sources

% population aged 15-19, % population aged 20-24 - Eurostat http://epp.eurostat.cec.eu.int; % population living in rural areas - World Development ndicators 2004, The World Bank; Absolute measure of poverty - World Bank Income Categories 2001; Relative measure of poverty - World Development Indicators 2004, The World Bank; Abortion - The World's Abortion Laws, 2004, Centre for Reproductive Rights www.crlp.org/pub_fac_abortion_laws.html; Religion - Foreign and Commonwealth Office 2005 country profiles www.fco.gov.uk

Comparisons between countries may not be reliable, since the source of information provided may be different for each.

* 1995 in elementary schools, 2000 in secondary schools ** not in Northern Ireland

Explanatory notes

Term used for sexuality education

SE - Sex/Sexual/Sexuality Education

SRE - Sex/Sexual/Sexuality Education plus reference to 'relationships'

EFL - Education for family life

OTH - Other (includes Health Education and Sexual Forming)

Sexuality education mandatory

-Yes x - No

Minimum school leaving age

Data from www.right-to-education.org

Age when first received sexuality education

Durex 2004 Global Sex Survey www.durex.com

Minimum standards set for sexuality education

-Yes x - No

Professionals responsible for teaching sexuality education

AT -Any teacher

DT - Dedicated teacher only (usually Biology teachers but also includes Religious Education, Moral Philosophy, Home

Economics, Citizenship, Human Study, Sport and Personal Social and Health Education teachers) AT/HP -Any teacher + health professional (usually school nurse but also includes school psychologists and school doctors) DT/HP - Dedicated teacher + health professiona AT/DT/HP - Any teacher + dedicated teacher + health professiona

Voluntary organizations (NGOs) involved

-Yes x - No

Comparisons between countries may not be reliable, since the source of information provided may be different for each.

Explanatory notes

Average age at first sexual intercourse

Data for Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg and Portugal was not available from this source and alternative data produced independently by each country was not included in its place as it was not thought to be comparable.

% 15 year old girls and boys who have had sexual intercourse

Figures for UK are England figures (Northern Ireland - data not available, Scotland - 34.6 (girls), 32.9 (boys), Wales - 40.1 (girls), 28.7 (boys)). Figures for Belgium are for Flemish region (Belgium (French) - 23.2 (girls), 34.4 (boys)).

Figures for Cyprus, Denmark, Iceland, Luxembourg and Norway appear in brackets because the data was independently produced by each country and is therefore not necessarily comparable: Cyprus is % sexually active before the age of 15; Luxembourg and Norway are % sexually active before the age of 16.

Birth rate among 15-19 year olds

Live births rate to 15-19 year olds per 1,000 female population. UK figure is based on an estimated population figure. Austrian figure is based on a provisional population figure. Rates based on 2003 data apart from: Estonia, Spain, France, Ireland - 2002; Italy - 2000; UK - 2001. Figure for Belgium appears in brackets because the data was independently produced by the country and is therefore not necessarily comparable.

Legal abortion rate among 15-19 year olds

Declared legal abortion rate to 15-19 year olds per 1,000 female population. UK figure is based on an estimated population figure. Denmark, France and Italy figures are based on provisional abortion figures. Ireland figure is an estimate. Rates based on 2003 data apart from: Denmark, Italy, Slovakia - 2002; Iceland - 2000; Spain, France, UK - 2001. Figures for Netherlands and Portugal are in brackets because the data was independently produced by the country and is therefore not necessarily comparable. Figure for Ireland is in brackets because the data is reliant on figures from the UK and does not include data for women who travel elsewhere for abortions.

HIV Incidence rate

Rates are for all age groups. 2003 data for all countries except Estonia, Italy and the Netherlands, which are 2002 figures.

* - HIV reporting in Italy exists only in six of 20 regions. Rates are therefore based on the population of these six regions.

** - New HIV reporting system started in the Netherlands in 2002 and cases were reported among adults and adolescents only.

% 15 year old girls and boys using contraception at last sexual Intercourse

Figures for UK are England figures (Northern Ireland - data not available, Scotland - 73.8 (girls), 81.2 (boys), Wales - 84.8 (girls), 82.4 (boys)). Figures for Belgium are for Flemish region. Belgium (French) - 81.5 (girls), 82.2 (boys). Figures for Denmark are in brackets because the data was independently produced by the country and is therefore not necessarily comparable.

Sources

Average age at first sexual intercourse - Durex 2004 Global sex survey - www.durex.com; % 15 year old girls and boys who have had sexual intercourse-Young People's Health in Context; Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International report from the 2001/02 survey. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2004 (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No 4). Edited by C. Currie, C. Roberts, A. Morgan, R, Smith, W, Settertobulte, 0. Samdal, and R. Barnekow; Birth rate among 15-19 year olds - www.eurostat. cec.eu.int; Legal abortion rate among 15-19 year olds - www.eurostat.cec.eu.int; HIV incidence rate - EuroHIV HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe, End Year Report 2003, No.70 - www.eurohiv.org; % 15 year old girls and boys using contraception at last sexual intercourse -Young People's Health in Context. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International report from the 2001/02 survey. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2004 (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No 4).

Comparisons between countries may not be reliable, since the source of information provided may be different for each.

24

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

25

Overall, religious influence in schools in Austria is strong, and sexuality education has been and remains a controversial subject. There is a common belief that young people become sexually active too early, and that as knowledge about contraception becomes more widespread, sexuality education is less important and unnecessary.

There is also a perception that sexuality education is not keeping pace with the current personal experiences of today's young people.

History of sexuality education

Prior to and during the nineteenth century, sexuality education was part of Catholic educational instruction. It focused on acts and behaviours that were forbidden, and the importance of remaining faithful before and within marriage. After the establishment of the Republic in 1918 and the election of the country's first female representatives, the female pioneers of the Social Democratic Party demanded organizations for sexuality education, with the primary aim of providing information about contraception. It was not until the end of the 1960s that the women's movement was able to exert pressure on lawmakers to address sexuality education. Around the same time, a meeting of experts was held that provided an extra 'push' for efforts to enact a decree related to sexuality education. The result was 'Sexuality Education in the Schools' (24 Nov 1970), in which sexuality education was introduced as an interdisciplinary principle of education.

Sexuality education has been mandatory in Austria since 1970, when guidelines were introduced for teachers. These guidelines - which are still in place today - state that the whole school should take part in sexuality education, that sexuality education should be integrated into Biology, German and Religious Education lessons, that interdisciplinary projects should be organized, and parents should be included. Parents are not able to withdraw their children from sexuality education lessons, but they are involved in conferences and are given information about material used in lessons.

Statutory regulation of sexuality education

Sexuality education is regulated by the Ministry of Education, which set out guidelines for provision in 1970.

Provision of sexuality education

Sexuality education, 'Sexualerziehung', starts in elementary school and is covered in four subjects - Biology, German, Religious Education and 'Sachunterricht' (Social Studies/Factual Education). Biological facts tend to be taught in Biology lessons, whereas topics dealing with moral views and values within the field of sexuality are covered in Religious Education.

Young people in Austria may stay in school until the age of 18. However, some leave school at age 15, and others at age 14 if they go into a profession. All Austrians receive sexuality education lessons at least three times during their school years - once in primary school (ages 6-10), twice in middle school (once at the beginning and once at the end) and a possible fourth session for those who continue in education from ages 14-18.

26

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

In elementary school, the topics covered in sexuality education include physiological differences between the sexes, procreation, pregnancy, development of the fetus, and menstruation. From the fifth to eighth grades the function of genitals is discussed, with a focus on procreation, menstruation and masturbation. Additionally, in the eighth grade conception, contraception, family planning, pregnancy, abortion, sexually transmitted infections and care of a newborn baby are covered.

The main teaching method is formal classroom instruction, with occasional demonstrations. For example, methods of contraception are shown and can be handled by pupils.

Quality and availability of sexuality education

Although sexuality education in Austrian schools is mandatory and has been established for two generations, only half of young people are thought to actually receive any school-based sexuality education. Generally, sexuality education in schools focuses on biological issues, with limited discussion of ethical, psychological and social views. All teachers are responsible for provision, but in reality only those who are confronted with sexual topics in the curriculum of their own subject provide information. Some observers believe that sexuality education is often neglected and provision is dependent upon individual teachers and schools, with many teachers lacking adequate training.

Regionally, sexuality education provision varies among the country's nine Lander, or provinces. For example, in Vienna it is publicly funded, but this is not the case in more rural areas. And large cities offer more opportunities for cooperation with NGOs and other institutions that offer sexuality education projects that cover topics of particular interest to young people. For example, the IPPF Member Association in Austria, Osterreichische Gesellschaft fur Familienplanung (OGF), assists schools in providing sexuality education and is partly funded by the Government and the Women's Department of the City of Vienna. Unfortunately, because most NGOs and institutions are only partly funded by the State, many schools cannot afford these externally-run projects. In some cases, schools do not even know that external assistance is available.

Moreover, it has been noted that when additional sexuality education projects run by NGOs are offered, pupils from Muslim households often do not attend.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

27

Public attitudes towards sex and sexuality education have become more liberal in recent years. However, a high-profile case of child abduction and murder in 1996 shocked the nation and may have contributed to the adoption of more cautious attitudes towards the sexuality of young people generally.

At the same time, this event underlined the need for the prevention of child abuse and the involvement of more social actors in sexuality education.

History of sexuality education

Belgium has three linguistic Communities (Flemish, Francophone and Germanophone). In the 1970s, a process of decentralization of political powers to the Communities began with regard to "matters related to the person". This included health promotion, and it gave the Communities full and autonomous political decision making over education. Since the beginning of the 20th century, there has also been a system of 'subsidiarity', which means that some governmental responsibilities have been subcontracted to civil society for its implementation. This has been the case, for example, for family planning services, sexuality education and the promotion of sexual health. Both the decentralization of powers to the Communities and the way the Communities have organized the practical implementation through civil society have led to totally different approaches to and regulations for sexuality education in the different communities of Belgium.

In Belgium, sexuality education is called 'relational and sexual education': 'Relationele en Seksuele Vorming (RSV)' in the Flemish Community and 'Education a la Vie Affective et Sexuelle' in the Francophone Community. Its teaching was authorized by a decree passed in 1984. With the emergence of HIV and the controversy over the liberalization of the abortion law in the 1980s, the focus of sexuality education shifted from medical information to a more holistic approach, integrating relational and emotional aspects and skills.

In Flanders in the early 1990s, the Minister of Welfare appointed dedicated sexuality education workers within family planning centres. However, this was followed in the mid-1990s by a major reorganization of the social sector. Family planning centres were absorbed into larger entities or social centres, which resulted in the redirection of prevention activities towards other issues, and severe cut-backs or elimination of sexuality education activities.

In the late 1990s, Sensoa, the Flemish IPPF Member Association, and the Forum Youth and Sexuality (composed of different NGOs and representatives of universities and various educational networks, including Catholic schools), developed a guide called 'Good Lovers' (Goede Minnaars), which outlined a single approach to sexuality education. By 2000, sexuality education was included as part of school objectives or end terms, which were introduced into schools and assessed as part of school evaluations. The objectives included support for the development of:

gender identity and roles

positive physicality and sexuality

sexual orientation tailored to the individual

28

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

the ability to achieve intimacy with others

acquiring sexual and relational morality

risk prevention (STIs, HIV/AIDS, pregnancy, sexual abuse)

The establishment of these objectives gave every pupil the right to sexuality education classes, and meant that schools could be held accountable for ensuring that every pupil received sexuality education. These standards are still in place today in Flanders.

In 1995 and 1997, respectively, the Brussels and Wallonia regional governments passed decrees authorizing family planning agencies to be paid and trained to offer sexuality education. Since 2000, various evaluations of the provision of sexuality education have influenced the Communities' policies. For example, the need to provide sexuality education in out-of-school settings was identified, and so this was introduced in some regions.

Provision of sexuality education

In Flanders, schools have considerable autonomy and can be set up independently of public authorities, providing they comply with legal and statutory requirements. Sexuality education can be taught from the age of six or even in kindergarten classes, and all topics are covered, but are tailored according to pupils' age groups.

Managers can assign sexuality education to specific teachers (e.g. Biology teachers) or to a group of teachers, or they can call upon external experts. Experts from Centres for General Welfare (Centra voor Algemeen Welzijnswerk or CAW) or Youth Action Centres (Jeugd Actie Centra or JAC) commonly use more interactive teaching methods and work with smaller groups.

The Flemish government considers Sensoa (the Flemish IPPF Member Association) its partner organization - the agency that implements the Flemish sexual health promotion concept. Sensoa has developed and implemented a new concept of sexuality education ('Good Lovers') and conducted regular public awareness campaigns, such as the 'Talk About Sex' CPraat over seks') campaign in 2005. Sensoa produces education materials (manuals for teachers and brochures for pupils and parents), has a permanent exhibition on sexuality education at the School Museum in Ghent, conducts mass media campaigns related to sexuality education, and provides sexuality education training. Some youth organizations, subsidized by the Ministry of Youth, and some health and welfare organizations, subsidized by the Ministry of Welfare and Health, provide materials and training for young people in out-of-school settings.

The Belgian Francophone IPPF Member Association (Federation La'i'que pour le Planning Familial et I'Education Sexuelle or FLCPF) is recognized as an entity of 'permanent education' (organisme d'Education permanente) by the Francophone Community. In the Francophone and Germanophone communities of Belgium, sexuality education is implemented by family planning centres, which are administered by FLCPF. Staff of the family planning centres are trained by FLCPF to provide sexuality education, particularly group sessions of sexuality education.

The sexuality education curriculum is incorporated into other curriculum subjects. For example, biological aspects are covered in Biology lessons, and moral and ethical aspects are covered in Religion and Philosophy lessons. Sexuality education is also included in the teaching of Social Skills, Education for Citizenship and Health Education. School managers are responsible for deciding how sexuality education is organized in each school.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

29

In the Francophone and Germanophone Communities, 90 per cent of sexuality education - both in and out of schools - is provided by trained family planning centre professionals. The other ten per cent is the responsibility of school-related support centres. Unlike in the Flemish Community, there are no specific objectives set for sexuality education in Francophone and Germanophone Communities. The quality of sexuality education depends on the efforts of each individual provider and their competence. Each school determines the level of priority of sexuality education in its own curriculum.

Statutory regulation of sexuality education

Policies relating to sexuality education are the responsibility of different ministries, primarily the Ministry of Education, but also the Ministry of Welfare and Health and the Ministry of Youth, other principals and managers of schools, health and youth centres, and (in Flanders) the management of Sensoa.

In Flanders, minimum standards for sexuality education have been formulated and integrated as cross-curricular goals, and schools must demonstrate their efforts to achieve these goals. In the Francophone and Germanophone parts of the country, no such standards exist.

Quality and availability of sexuality education

The quality of sexuality education is still dependent upon the efforts and competence of individual providers, and in Francophone and Germanophone Communities, individual school policy determines prioritization of the subject.

Efforts to evaluate the provision of sexuality education have been made by the National Inter-Ministerial Commission Report of young people's sexuality (2001), which recommended improving sexuality education in and out of school; the inventory of sexuality education provision (2003); and the Marechal Report (2004), which recommended promoting sexuality education.

30

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

Attitudes towards sexuality, homosexuality and pre-marital sex, particularly with regard to young people in Bulgaria, vary according to individual cities and among different age groups. For example, well-educated young people and young people from large cities are more comfortable and liberal when it comes to discussing sexuality issues than are students from rural areas.

History of sexuality education

The first efforts to introduce sexuality education in schools took place in the 1970s, when schools invited lecturers to make presentations on the topic. And in the 1980s, a discipline called 'In the World of Intimacy' was approved and used optionally in high schools. Yet a 1997 study found that, up to then, there was a general absence of sexuality education in Bulgarian schools: "... students are taught a total of only two hours on the biological differences between the sexes ... [t]here is a total lack of formal education with regard to the psychological and social aspects of sex." Moreover, the study stated that adolescents' "sexual knowledge is still obtained 'in thestreets'"(Okoliyski, 1997).

Starting in the 1990s, newly established NGOs began to provide sexuality education using an interactive approach to teaching. Since 1996, the Bulgarian Family Planning and Sexual Health Association (BFPA) - the IPPF Member Association in Bulgaria - and the Ministry of Education have used peer education methods to teach sexuality education in and out of schools. Special educational materials and a manual have been produced on sexual health and life skills in an effort to prevent teenage pregnancies and STIs. There have also been informational campaigns and programmes funded by IPPF, UNFPA, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), Population Services International (PSI) and PHARE (an instrument financed by the European Union to assist accession countries in their preparation to join the European Union).

In 2001, UNFPA funded the creation of a 'Sexuality and Life-Skills Educational Set', which consisted of a manual for teachers, a notebook for students and a manual for parents, which were printed in 2005. Negotiations with the Ministry of Health to introduce the material into schools for students from the age of 11 (fifth grade) were unsuccessful. However, with a new government in place, negotiations continue, and there are efforts to introduce obligatory sexuality education in schools.

Provision of sexuality education

Sexuality education is not mandatory in Bulgaria, and there are no minimum standards for provision. In many schools, parents and students can choose sexuality education as an optional discipline. Where it is included in school curricula, it is as a topic in the form-tutor's lesson (special hours focused mainly on administrative issues) and is usually taught using a holistic approach and interactive techniques. However, more formal lessons are favoured in State schools.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

31

Topics strictly follow the age characteristics of the pupils, starting with general information on the male and female reproductive systems in the fifth grade (ages 11 to 12) and continuing with topics such as HIV and AIDS, STIs, contraception and violence in eighth through twelfth grades (ages 14 to 19).

In 2004, as part of a GFATM programme, a national initiative was launched in 13 cities to train school psychologists, medical specialists and, in some cases, Biology teachers, to lead sexuality education lessons and provide counselling within schools.

NGOs - particularly BFPA and the Bulgarian Youth Red Cross - are involved with sexuality education provision at the request of individual schools. BFPA provides information and education activities to the general public, with particular emphasis on young people, and offers sexuality education sessions for 14 to 19-year-olds (IPPF, 2005). There are also NGOs working on sexual health education in Bulgaria for specific marginalized groups. In general, where funding is available, the NGO sector supports sexuality education and uses interactive peer education methods.

Statutory regulation of sexuality education

While sexuality education is not currently mandatory in Bulgaria, new policies governing sexuality education are the responsibility of the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Youth and Sport.

Quality and availability of sexuality education

Some observers believe that, where sexuality education does exist in Bulgaria, it is adequate and modern. But there is thought to be insufficient coverage of sexuality education throughout the country. Classes are not held regularly, and teachers are not adequately trained to deliver sexuality education. Virtually no sexuality education takes place in rural areas, while in urban areas provision depends upon the motivation of school authorities and local communities. Peer education as a method of sexuality education is believed by some observers to be effective in Bulgaria as long as it is specific and tailored to different educational levels.

Bulgaria is scheduled to join the European Union in 2007 and it is believed that accession might bring about changes in sexuality education policies and provision.

32

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

Although in recent years attitudes related to young people's sexuality appear to have become more liberal than in the past, conservatism is still the norm. It appears that gender inequity and cultural conservatism are common, the church has a strong influence, and sexual and reproductive health and sexuality education sources and services for young people are limited.

Research carried out among young people indicated that young people in Cyprus have limited knowledge of sexuality and sexual and reproductive health (Kouta-Nicolaou, 2003). Both quantitative research (ASTRA, 2006) and qualitative research among young people in Cyprus confirm these findings, and also suggest that confusion is prevalent among young people when it comes to attitudes on controversial issues such as homosexuality and abortion.

However, in a study conducted on behalf of the Youth Board of Cyprus in 2002, 95.3 per cent of respondents agreed that sexuality education should be offered, and 69.3 per cent said that it should be offered in schools (Gregoriou et al, 2005).

History of sexuality education

Sexuality education was introduced in Cyprus by the Cyprus Family Planning Association (CFPA) in 1972. In 1979, the CFPA conducted a national survey on the need for sexuality education, which led to the formation of a multi-disciplinary committee on the topic. In 1992, the Ministry of Education decided that Health Education should become mandatory in school curricula, and family and sexuality education was incorporated into the Health Education curriculum. In the same year, many school teachers, health visitors and CFPA staff were trained to teach Health Education. In 1993, Health Education committees were formed in all schools, although for the most part these committees remain inactive.

Since 2002, pilot sexuality education programmes have been implemented in six high schools, with the aim of establishing more widespread and comprehensive sexuality education. However, no minimum standards for provision of sexuality education have been set and, as of 2006, no expansion of the pilot project is envisaged.

Statutory regulation of sexuality education

The Ministry of Education and Culture has authority over primary and secondary education in Cyprus. School officials are also involved, as are the Education Committee of the Cyprus Parliament and the Multi-Disciplinary Advisory Committee. To date, there is no statutory provision on sexuality education.

Provision of sexuality education

School attendance in Cyprus is mandatory for nine years (usually up to the age of 15), although most young people stay at school for 12 years (usually until age 18). The pilot sexuality education programme is known as 'Sexuality Education and Interpersonal Relationship Education'.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

33

Where it is taught, it is introduced in high school to pupils aged 14-15) and is provided by school teachers, mainly biologists. Apart from this pilot sexuality education programme, references to related topics are made during other classes throughout the education system, such as Biology, Home Economics and Religion. The subject of "Family Education" was recently introduced as an optional class in senior high schools (lyceums). In addition, health visitors, the CFPA and other expert visitors occasionally serve as guest lecturers or educators. The most common form of instruction is formal classroom teaching, but interactive workshops, peer education and multimedia methods are also used.

The CFPA advocates for the implementation of Sexuality Education in schools, and is involved in the promotion, design and implementation of the sexuality education curriculum and the training of teachers. The Association produces and disseminates educational material, runs workshops on sexuality education and sexuality awareness for young people, and addresses the general public through information campaigns.

Quality and availability of sexuality education

Observers say that no progress has been made since the implementation of the pilot sexuality education programme in 2002. Moreover, it has not been evaluated by the students participating in the programme, and the programme has not been extended or formalized. A major obstacle to the efficient implementation of such programmes is the lack of training for teachers and the necessary funding. Since the Ministry of Education has no set strategy or position regarding sexuality education, teachers often feel hesitant to present specific positions or opinions, and do not want to undertake such responsibility. The CFPA is usually welcomed and often invited as a guest lecturer, but the association does not have the funds or resources to cover the needs of the entire island. Furthermore, there is a notable discrepancy regarding access to information between urban and rural areas, since youth information centres that can provide informative material and referrals to young people are either completely absent or scarce in rural areas.

Currently the CFPA is working towards the production of a manual on sexuality education for elementary school teachers, to be followed by the production of exercise books for pupils and a workshop for teachers on the use of the manual.

34

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

Attitudes towards the sexuality of young people in the Czech Republic can be described as generally tolerant, but they vary depending upon people's religious beliefs. Some opponents of sexuality education maintain that the family should be the institution providing young people with this information.

History of sexuality education

Under Communist rule in the former Czechoslovakia, sexuality education was virtually non-existent due to the prevalence of puritanical thinking (Friedman, 1992). From the mid-1940s, the inclusion of family life/sexuality education in the curriculum depended on the head of the school, who had the option of inviting a guest lecturer to give presentations to students. This type of education differed widely and was not very effective (Buresova, 1991). In 1956, the Ministry of Education ruled that one sexuality education lecture was required for 14 year olds. Responsibility for sexuality education was coordinated in 1971, by Government Resolution No. 137, which specified family life education at all school levels in preparation for harmonious, stable family life and parenthood. In 1972 The Ministry of Education issued "Guidelines for Parenthood Education at Elementary Nine-year Schools", which determined the contents of education for marital life and parenthood in curricula. The former Czechoslovak Family Planning Association (SPRVR), established in 1979 as a section of the Czechoslovak Medical Society, had been at that time cooperating with the Ministry of Education to strengthen the position of parenthood education and influence the preparation of guidelines. "One objective was to provide knowledge on sensitive topics to Elementary School children before they encountered misinformation elsewhere." (David, 1999)

Since the end of Communist rule, the Catholic Church has opposed sexuality education and, efforts to improve teacher training in the area of sexuality education and to publish sexuality education textbooks have been greatly hampered by the Catholic Church (David, 1999). According to The International Encyclopedia of Sexuality, Volume I - IV 1997-2001, "basic knowledge about sexual anatomy and physiology" was part of the school curriculum, but information about contraception, sexual hygiene, and safer sex practices were rarely and inconsistently addressed (Zverina, 1997).

Until 1989, sexuality education was mainly included in Biology lessons. It was later included in 'Care of Child', 'Specific Education for Girls', 'Education for Responsible Marriage and Parenthood' and 'Family Education'. In 1994/95, there was much debate about whether to make sexuality education an obligatory part of the curriculum. A modified programme, which the Ministry of Education supported, was developed by various academics, sexologists and teachers. However, a total reorganization of the educational system is currently underway, and this may lead to greater decision-making power for individual schools and therefore changes in curricula.

Statutory regulation of sexuality education

Sexuality education is mandatory in The Czech Republic, with no opt-out clauses. It is taught by teachers within the framework of other subjects (Biology, Citizenship, and Family Education) although not as a standalone subject.

SEXUALITY EDUCATION IN EUROPE - A REFERENCE GUIDE TO POLICIES AND PRACTICES

35

Standards of sexuality education have been set by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and are currently under revision. An extensive document, 'Framing Educational Programme', has been produced by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports and defines the minimum standards for sexuality education.

Provision of sexuality education

Sexuality education begins in the second year of primary school, when pupils are seven years old and school directors and teachers are responsible for provision. School teachers are the most common providers of sexuality education to young people, and formal classroom teaching is the most frequently used method. The sexuality education curriculum is said to be comprehensive, with all topics covered. The various topics are included in different school years according to the age range of the class. Sexuality education is designed to prepare students for responsible sexual activity and stresses using contraceptives, partnership relations and preventing sexually transmitted infections. It also warns students about the sexual abuse of children and sex crimes, and promotes tolerance towards homosexuals.

Many NGOs are also involved in providing sexuality education, primarily the IPPF Member Association in the Czech Republic, Spolecnost pro planovani rodiny a sexualni vychovu or Czech Family Planning Association (formerly Czechoslovak Family Planning Association). It provides information and education for the general public and organizes seminars, conferences and lectures on sexuality education aimed at all age groups.