The Importance of Looks in Everyday Life

Elaine Hatfield, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA

Susan

Sprecher, ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY

STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS

SUNY Series in Sexual Behavior, Donn Byrne and Kathryn Kelley, Editors

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

© 1986 State University of New York

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Hatfield, Elaine. Mirror, mirror.

(SUNY series in sexual behavior)

Bibliography: p. 377

Dedicated to

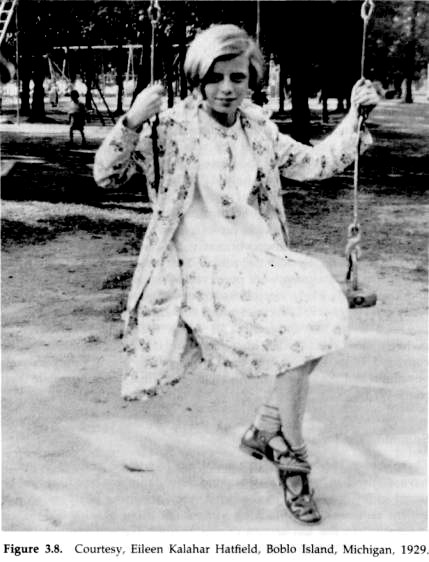

Charles Hatfield and Eileen

Hatfield and Charles William Fisher and

Abigail Sprecher Fisher

List of Tables

Acknowledgments

Foreword

Preface

Chapter 1 GOOD LOOKS - WHAT IS IT?

Chapter 2 WHAT IS BEAUTIFUL IS GOOD: THE MYTH

Chapter 3 THE UGLY: MAD OR BAD?

Chapter 5 MORE INTIMATE AFFAIRS

Chapter 7 HEIGHT, WEIGHT AND INCIDENTALS

Chapter 8 PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS: THE REALITY

Chapter 9 BEAUTY THROUGH THE LIFE-SPAN

Chapter 10 THE UGLY TRUTH ABOUT BEAUTY

Chapter 11 SUSAN LEE: A CASE HISTORY

Chapter 12 SELF-IMPROVEMENT—IS IT WORTH IT?

Societies' Preferences in Appearance

Satisfaction with Body Parts

The Relationship Between Looks and Career Success

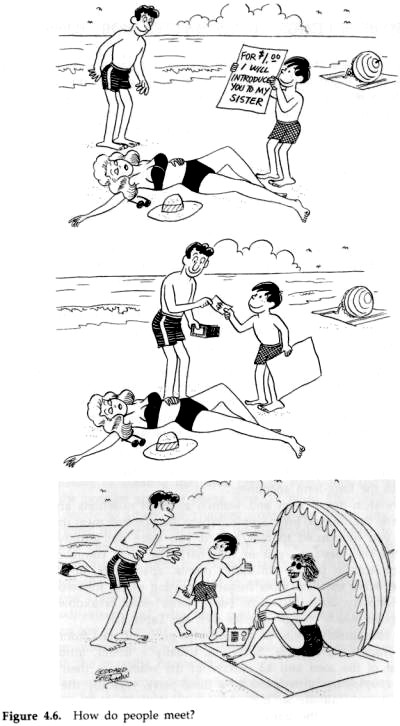

Where Do Most College Couples Meet?

The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale

Percentage of Compliance with Each Request

Sexual Traits

The Beliefs vs. The Reality

6.3. How Intimate Is Your Relationship?

6.4. Reasons for Entering a Sexual Relationship

7.1. Acceptable Weights for Men and Women

7.2. Percent of Men and Women Exceeding Acceptable Weight by 20 Percent or More. A United States Health and

Nutrition Examination Survey, 1971-1974

9.1. The Impact of Age Upon Body Image

9.2. Consistency of Appearance and Self-Esteem, Body Satisfaction, and Current Happiness

11.0. Scores on the MSIS

12.1. The Effect of Dramatic

Changes in Appearance

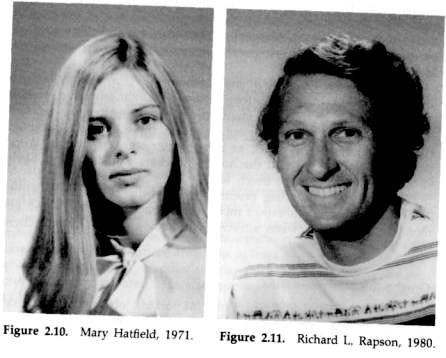

We would first like to thank our families for their ideas and support of this book. Elaine would like to thank Richard and Kim Rapson; Charles, Eileen, and Mary Hatfield; and Patricia, James, Jeremy, Joshua, Jordan, and Shayna Rich. Susan would like to thank Charles Fisher; Milton, Shirley, Terry, Dawn, Larry, Jan, and Cynthia Sprecher; and Bill, Sharon, Rebecca, and David Ring.

We would also like to thank our colleagues and friends who read drafts of the book: Geraldine Alfano, Leslie Donavan, Diane Felmlee, Gerald Marwell, Kathleen McKinney, Nancy Neuman, Gerelyn O'Brien-Charles, Terri Orbuch, Patt Schwab, and Robert Smith. Thanks to Amy Grever and Carol Yoshinaga for typing this manuscript and to Chris Peters from the University of Wisconsin for providing assistance on Illustrations. Charles Fisher helped secure permission to use the various tables, graphs, and quotations.

To all the men and women interviewed for the book we express our gratitude.

CREDITS

Figure 1.3 Reprinted with permission from Body and Clothes, by R. Broby-Johansen (Copenhagen: Gyldendalske Boghandel, 1966). Figure 1.5 Reproduced with permission of Pinacateca di Brera, Milan. Figure 1.6 Reprinted with permission from The Gibson Girl by S. Warshaw (Berkeley, Calif.: Diablo Press, 1968).

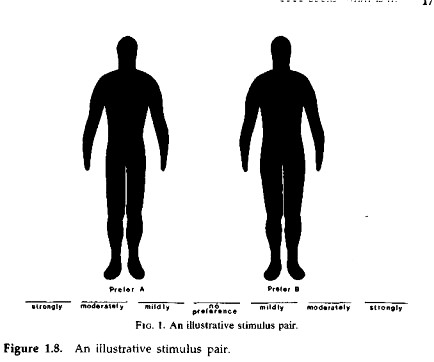

Figure 1.7 Illustration first appeared in Wiggins, Wiggins, and Conger, "Correlates of heterosexual somatic preference," /. of Personality and Social Psychology © 1968 by the American Psychological Association. Reprinted by permission of the author.

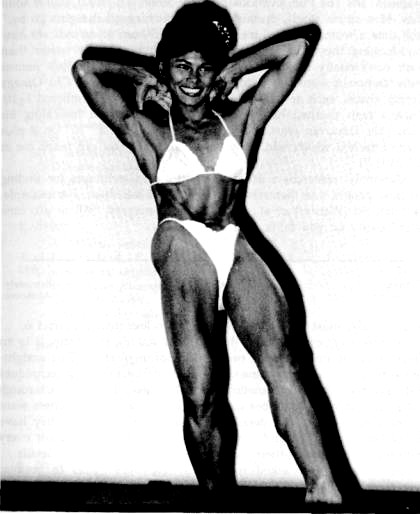

Figure 1.8 Reprinted with permission of Paul J. Lavrakas, "Female Preferences For Male Physiques," /. of Research in Personality 9:324-334. Figure 1.9 Reprinted with permission of Janet C. Vidal, 1984. Figure 9.4 © 1982 Nancy Burson in collaboration with Richard Carling and David Kramlich. Figure 9.9 Courtesy Soloflex, Inc.

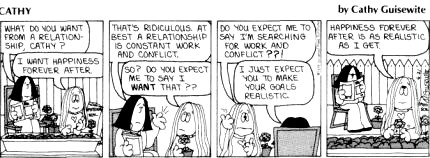

Figure 11.2 © 1981, Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Figure 12.1 Courtesy Baker-Van Dyke collection.

It is a pleasure to be asked to say a few prefatory words to this volume, which brings together under one cover for the first time what behavioral scientists have learned about the effects of physical attractiveness. Writing this introduction is a special pleasure because the book's senior author, Elaine Hatfield, has played a major and seminal role in the development of this knowledge.

Because the general public has shown a great deal of interest in information about the effects of beauty, in the recent past many journalists, freelance writers, and others have requested reprints of studies for writing their own books about the impact of physical appearance in our lives. However admirable these efforts may be, it is safe to say that none can have the authority and perspective of the pages that follow.

For one thing, researchers in an investigative area know where the bodies are buried—the "reasonable" hypotheses that turned out not to be so reasonable after all and whose disconfirming data now languishes

Al *

in dark file drawers, never to see the light of publication and dissemination. For another, researchers know how to evaluate and weigh the quality of data and know where the subtle interpretive traps lie. Most importantly, researchers who have worked on a problem for a long time remember when what seems so obvious and readily accepted today was not only not obvious in the past but even failed to meet rudimentary standards of common sense. In the case of the effects of physical attractiveness, they remember when there was a scientific taboo against recognizing and systematically studying this variable at all.

This taboo against the investigation of appeariential variables upon human behavior reigned not in psychology's dim and distant past, but was alive and well until relatively recently. Just twenty years ago, Gardner Lindzey, president of the Division of Personality and Social Psychology of the American Psychological Association, took the field to task for ignoring the influence of morphological variables, "even aesthetic attractiveness," upon behavior. His remarks, many of which were scathing, detailed many reasons for the then prevalent belief in the scientific community that the study of appeariential variables was an "unsanitary practice," one that relegated those who persisted in exploring them to the tawdry side of the street in the social and behavioral sciences.

A few years after Lindzey's comments, Elliot Aronson (1969) an eminent researcher in the area of interpersonal attraction, commented upon the curious absence of systematic examination of the effect of one morphological variable, physical attractiveness, upon behavior. He also offered one possible reason for its neglect. "It may be," he said, "that, at some level, we [researchers] would hate to find evidence indicating that beautiful women are better liked than homely women— somehow this seems undemocratic." Presumably, it would have been equally uncomfortable for researchers, most of whom at that time were male, to find that handsome men were better liked than homely men. His comment, however, reflected the belief of the day (still covertly held by some researchers in contrary to established fact) that if physical attractiveness did by any chance have some impact, that impact was probably confined to women—and to women of dating and mating age at that.

These professional injunctions to those attempting to understand the dynamics of human social behavior had little noticeable effect. Then, in 1966, Elaine Hatfield and her colleagues published a study whose findings could not be ignored. The occasion for the study was Hatfield's employment by the University of Minnesota Student Activities Bureau, requiring her to help construct the university's program for "Freshman Welcome Week". That this new Ph.D., a top-rated graduate of the Stanford doctoral program in psychology, found employment only in

an auxiliary service agency while her fellow male students secured prestigious professorships in psychology departments reflected the times and a different kind of societal taboo. Trained as a researcher and given a benevolent head of the bureau (who later recalled to a group of Minnesota faculty some of the unusual requisitions for research materials he signed while Hatfield was in his employ, including one, he remembered, for "chocolate-covered grasshoppers"), Hatfield saw her assignment to "do something" for Welcome Week as a research opportunity.

So, interested in the dynamics of interpersonal attraction, Hatfield decided to put together a "computer dance" for the incoming freshmen, a dance where purchase of a ticket would guarantee the student a date. The research question she asked was simple: Which dates, randomly paired, would like each other? Her hypothesis also was simple: People of relatively equal "social desirability" would hit it off better than people mismatched in social assets. But what determines a person's social desirability? "Personality" surely would be important, she reasoned. Fortunately, all incoming freshmen had completed various kinds of personality assessment devices, so information on this score was available. "Social skills," too, could be expected to play a role, and information on this dimension was also available. "Intelligence," especially in the college setting, undoubtedly would be an important asset, and, of course, all freshmen had submitted grade averages and completed aptitude tests to gain admittance to the university. These attributes headed the lists of all previous studies asking people what they looked for and valued in a date or mate. Thus, personality, social skills, and intelligence were to be combined into a "Social Desirability" score for each person buying a ticket to the dance.

At the last minute, however, Hatfield had an afterthought. She asked the students selling tickets to the dance to jot down their impressions of the physical attractiveness of the purchaser. Needless to say, these impressions provided only rough assessments. In the general confusion surrounding the ticket sale and in the few seconds it took to take money, make change, and issue a ticket, the ticket-taker's impression could not have much reliability and validity and thus could not be expected to predict much of anything. Nevertheless, the data were collected and analyzed.

I was a graduate student in the Laboratory for Research in Social Relations at the time and remember well when Hatfield was asked how the computer dance study had "turned out". "It was a flop," she said. Her "matching hypothosis" had not been confirmed. People of equal social desirabilities did not like each other better than mismatches. In fact, she went on, there was only one predictor of whether a person would like his or her date and, in the case of men, whether he would actually make an effort to contact the date again. That predictor was

those rough physical attractiveness assessments. The more physically attractive a person was, the more they were liked by their date. This predictor held true whether the person was a woman or a man.

This news was greeted by total silence. Finally, someone said, "That was it?" "That's it," she replied. "Intelligence, social skills, personality— they didn't predict." Needless to say, these results cast a pall over the lab. The finding was embarrassing. Among other things, it gave the lie to our collective professions that what we really valued in potential dates and mates was a good personality—honesty, kindness, and all the other sterling virtues. The finding also mocked the advice, then routinely given to those who found themselves lonely and rejected, to wit: "Improve your personality and your character!"

It was not, of course, that we didn't suspect appearance played some role in how a person was regarded by others. But this was the early sixties—when appearance was almost universally regarded as a frivolous and superficial attribute. At this time people requesting plastic surgery to modify some aspect of their appearance were routinely subjected to tests to ascertain that they were free of psychopathology— a certification difficult for the candidate to achieve since a request for plastic surgery was itself considered a symptom of neuroticism. During this era the only reasonable justification for orthodontal surgery and treatment, or indeed routine dental treatment, was considered, by insurance companies, dentists, and clients alike, to be improvment of "function"—not aesthetic appearance.

All that, and more, has changed. For example, judges, juries, and lawyers representing clients whose appearance has been adversely altered through the negligence of others now take into consideration more than just impaired physical function. The probability that a disfigurement also leaves the victim with impaired self-esteem and impaired social and economic opportunities is also considered. The dental profession now worries about more than whether their treatment will leave the patient with the perfect "bite". Finally, therapists and counselors do not automatically conclude that social rejection is always the result of unattractive interior qualities.

Many of these changes can be traced back to that first uncomfortable and embarrassing finding, and to the fact that Elaine Hatfield was not content to bury her data. Against the advice of some senior colleagues, who believed the finding was "theoretically uninteresting" and therefore unworthy of consideration by professional journals, she wrote up her "serendipitous finding," as she called it then, and so the effort to trace the dimensions of this variable upon people's lives began in earnest.

All good researchers must be willing to observe not only that the emperor's new clothes are not magnificent but, when necessary, to call

attention to the fact that he seems to be parading around in his underwear. Fortunately, researchers are not often called upon to make such assertions. When they are, however, and when they persist in their contention that we seem to be kidding ourselves, our understanding of our world changes; thus, our ability to make reasonable and considered choices for ourselves and for our own lives expands.

Since providing better information for making life choices is the bottom line of all research, I was particularly pleased to see that the relative importance of physical attractiveness is not ducked in the final chapters of this book. Just as it was wrong and misleading to underestimate the impact of physical attractiveness in peoples' lives, it is surely equally wrong to overestimate it—to forget that decisions on expending time, money, and energy to improve or maintain attractiveness have to be made in the context of many other considerations, and that while making gains on the attractiveness dimension, other things, often of greater value, may be lost.

I cannot resist concluding these comments with the most recent example of the effects of a single-minded determination to place beauty above all other considerations. The example comes not from the United States, with its multibillion dollar cosmetic industry and infinite numbers of diet centers, fat farms, and physical fitness and rejuvenation spas. It comes from Communist China. Concerned with the growing number of unwed men and women in their country, the Chinese government recently sponsored a nationwide campaign to "pair them off". To that end, "night dancing parties," marriage introduction services, and organized singles outings were introduced. The government's campaign, however, was a failure. Why? Apparently there are not enough "beautiful people" to go around. The People's Daily (as reported by the Associated Press in The Minneapolis Star and Tribune, August 31, 1984) complains: "Men's and women's criteria for selecting mates are not practical. The situation is unsettling. When matchmaking workers ask a man what kind of mate he desires, he says, T want a beautiful woman.' The result is they do not find anyone suitable." Apparently the joys of marriage and parenthood combined with governmental sanction and enticement do not outweigh, at least in contemporary Chinese eyes, the discomfort of being paired with someone who does not meet their high standards of beauty.

Is this subject "theoretically uninteresting"? That apples fall down, rather than up, must have seemed just as theoretically uninteresting at one time. But no one interested in predicting the trajectory of an apple loosed from its bough could afford to ignore that mundane fact, and

no effort to understand human behavior in general, and social interaction in particular, can afford to overlook the factor of appearance.

Ellen Berscheid

Minneapolis, Minnesota September, 1984

We all face a fundamental paradox. We have to admit that appearances matter. We know that small details of our appearance can be critical determinants of how well we will do in love, at work, and in life. And yet . . . and yet. Each of us knows we do not really "measure up," and we feel slightly ashamed that we expect other people to do so. How can we deal with this dilemma? This book will attempt to address that issue.

In chapter 1 we ask, "What is good looks?" and review what anthropologists, sociologists, and psychologists know about that question. We examine whether there is any agreement both between and within cultures as to what is considered beautiful or handsome.

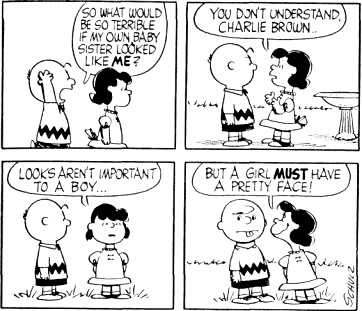

In chapters 2 and 3, we review the evidence that, in the main, people believe "what is beautiful is good and what is ugly is bad." We will discover that people believe good-looking people possess almost all the virtues known to humankind, and that, as a consequence, they treat the good-looking/ugly very differently.

In chapters 4, 5, and 6, we discuss how well attractive versus unattractive persons fare in the dating, mating, and sexual marketplaces. We review several studies indicating that although most people desire attractive partners most often, because of the dynamics of supply and demand, they end up pairing with someone of about their own level of attractiveness.

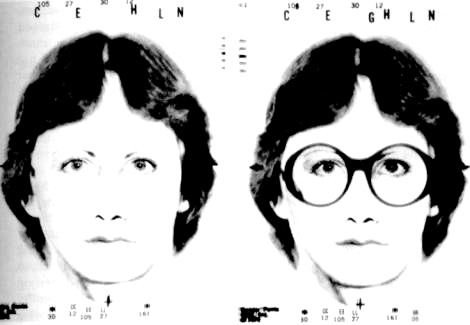

We turn to more specific physical characteristics in chapter 7. We discuss the stereotypes held about people with specific physical characteristics. We explore the impact of height, weight, and such incidentals as hair color, eyes, and beardedness on our social encounters.

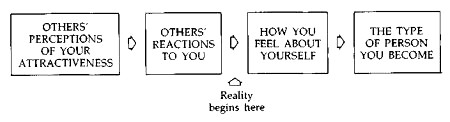

In time, most people come to see themselves as others see them— to act as others expect them to act. Eventually, good-looking and unattractive people become different types of folk in their self-images, personalities, and interactional styles. In chapter 8, we examine this reality of physical attractiveness.

In chapter 9, we trace the impact of beauty through the life cycle. We examine what happens to our bodies as we age and how this change affects other areas of our lives. We discover that beauty begins to matter in the nursery and continues to matter through old age.

Throughout the majority of the book we discuss the pleasant aspects of being attractive. Yet every silver lining has its cloud. The ugly truth about good looks, the disadvantages, are discussed in chapter 10.

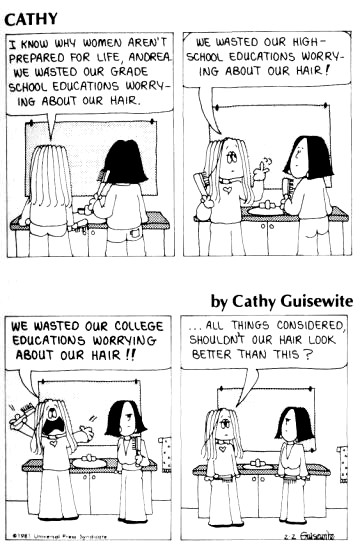

This discussion leads us to the question of what to do if we are unattractive. Is it worth it to try every means to make ourselves more appealing? Cosmeticians, beauticians, orthodontists, and plastic surgeons would lead us to believe that we can (and should) do all we can to improve our looks. But such enterprises have serious costs even in the short run. They are expensive, exhausting, and require us to focus almost every waking moment on being something we are not. Worse yet, people banking everything on looks may find they have won the battle but lost the war. In the end, and in spite of evidence we have cited heretofore, factors other than beauty turn out to be important in producing life-long happiness. In chapters 11 and 12, we present what social psychologists and therapists have to say about the advantages and disadvantages of trying to improve our appearance. We learn that most of us do our best if we engage in fulfilling activities—concentrating on sharpening our skills in intimacy, pursuing friendship, investing energies in our careers. Apparently, what is important is to accept ourselves as we are and to set out on a search for what life has to offer.

When we were deciding how to write this book, our first step was to gather a great sampling of people. We sought people very different from one another—men and women of various races, ages (3 to 97), and occupations; people strikingly good-looking to downright homely; people who had very different life experiences. These are the people who make up THE GROUP. We began by asking THE GROUP: "If you came upon a 2,000 ad. computer capable of answering your deepest, most hidden questions about beauty and handsomeness, what would you ask?"

THE GROUP'S reply was quick: "What is it?" They mentioned people they thought were strikingly beautiful or handsome ... or painfully ugly—"What makes these people so distinctive?" Then, THE GROUP began, shyly, to ask more personal questions: "Do you think I'm good-looking?" "What's my best feature?" "My worst?" "What would I have to do to be really good-looking?" "What's it like to be extraordinarily good-looking?"

1

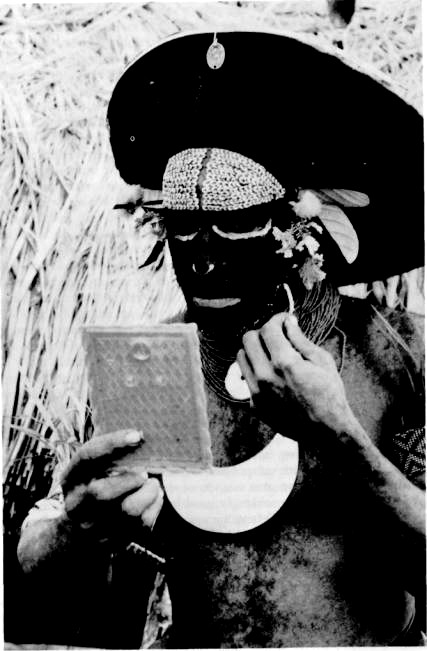

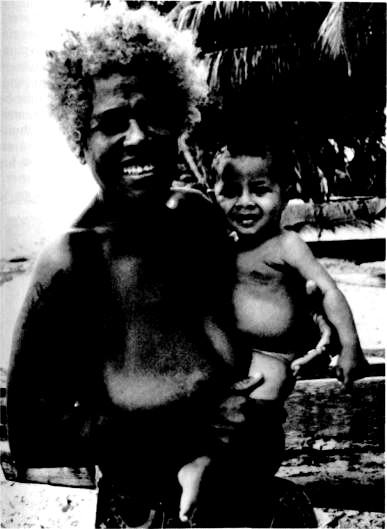

Figure 1.1. A tribesman admires his ceremonial appearance. Photograph by Jack Fields, 1969.

In this book, we will try to provide social psychologists' answers to all these questions and more. But first, we will have to begin at the beginning and discuss, "What is this thing called good looks?"

• How would you define good looks? Could you explain what a "beautiful woman" and "handsome man" are to a blind person?

• Who are the most attractive men and women you ever saw? What makes them so appealing?

• Who is the homeliest person you ever saw? What made him or her so unappealing?

GOOD LOOKS—WHAT IS IT?

Webster's New World Dictionary defines good looks as:

BEAU TI FUL (byoot'e fel) adj. having beauty; very pleasing to the eye, ear, mind, etc. —interj. an exclamation of approval or pleasure —the beautiful 1. that which has beauty; the quality of beauty 2. those who are beautiful — beau'tifully (-e fie, -e fel e) adv. SYN.—beautiful is applied to that which gives the highest degree of pleasure to the senses or to the mind and suggests that the object of delight approximates one's conception of an ideal; lovely refers to that which delights by inspiring affection or warm admiration; handsome implies attractiveness by reason of pleasing proportions, symmetry, elegance, etc. and carries connotations of masculinity, dignity, or impressiveness; pretty implies a dainty, delicate, or graceful quality in that which pleases and carries connotations of femininity or diminutiveness; comely applies to persons only and suggests a wholesome attractiveness of form and features rather than a high (From D. B. Guralnik, Webster's New Simon and Schuster, 1982], 124, 634.)

degree of beauty; fair suggests beauty that is fresh, bright, or flawless and, when applied to persons, is used esp. of complexion and features; good-looking is closely equivalent to handsome or pretty, suggesting a pleasing appearance but not expressing the fine distinctions of either word; beauteous, equivalent to beautiful in poetry and lofty prose, is now often used in humorously disparaging references to beauty—ANT. ugly HAND-SOME (han'sem) adj. [orig., easily handled, convenient < ME. handsom: see hand & some1] 1. a) [Now Rare] moderately large b) large; impressive; considerable [a handsome sum] 2. generous; magnanimous; gracious [a handsome gesture] 3. good-looking; of pleasing appearance: said esp. of attractiveness that is manly, dignified, or impressive rather than delicate and graceful [a handsome lad, a handsome chair] —SYN. see beautiful —hand'somely adv. — hand'someness n. World Dictionary: Edition 2 [New York:

By physical attractiveness we mean that which best represents one's conception of the ideal in appearance and gives the greatest pleasure to the senses.

At first glance, it seems easy to say what is appealing, what is not. For example, early I.Q. testers assumed that any intelligent person could easily tell which is which. The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale (1937 edition) asked children to look at two line drawings and to indicate which woman was pretty and which was ugly. The "pretty" face had fine, delicate features and a neat hairdo, while the "ugly" face had a large nose, a large mouth, and unkempt hair. Obviously, the test constructors assumed they knew what beauty was and that any "bright" child would agree with them. Unfortunately, however, things are not so simple. The search for a standard of beauty has been a long one.

The Search for a Universal Beauty

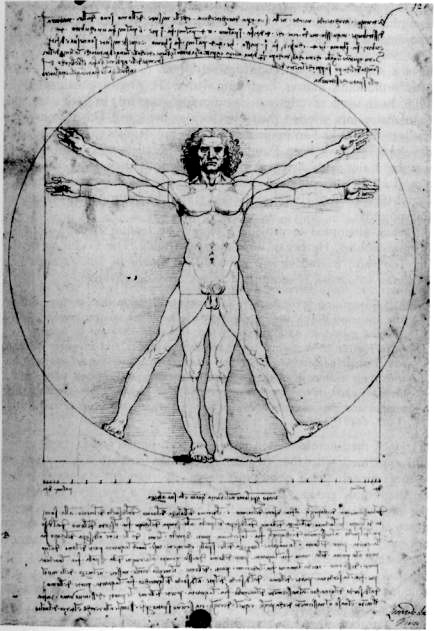

Thoughtful people have spent an enormous amount of effort trying to discover what is universal about beauty. Greek philosophers were convinced that the Golden Mean was the basic standard of beauty (see Hambidge 1920; or Plato 1925). The Golden Mean represented a perfect balance. To be extreme was to be imperfect. (So much for the rare and exotic.) The Greeks' theory was elegantly, brilliantly simple. Unfortunately, it was wrong. The Romans were more interested in the rarities of particular faces and persons. Conceptions of ideal beauty resurfaced in the Christian era (see Figure 1.2).

In more recent times, Charles Darwin's efforts to define beauty are worth noting. Charles Darwin realized it was critically important for anthropologists to know what various peoples considered sexually appealing. Only then could they predict the course of sexual selection and, ultimately, human evolution. Darwin tried but failed. After surveying the standards of various tribes throughout the world, Darwin concluded: "It is certainly not true that there is in the mind of many any universal standard of beauty with respect to the human body" (1952, 577).

Henry T. Finck (1887) was the first early psychologist to pose a theory of beauty. Finck is a delight to read. It makes one feel smugly superior to encounter someone so self-righteous, so opinionated . . . and so wrong. Finck's singular thesis was that primitive people were nature's "experiments." Humankind started out, he thought, exceedingly ugly. But humankind continued to evolve, becoming more perfect, better-looking, all the time. Finally, evolution and good looks reached a pinnacle in the upperclass English gentleman. (Luckily, Henry Finck happened to be in just this category.)

Figure 1.2. Leonardo da Vinci, Illustration of Proportions of the Human Figure, c. 1485-1490, pen and ink, 13% X 9%.

This tendency—to assume our own group contains the best of everything—is common. One example: Dental surgeons face the extraordinarily difficult task of developing a universal standard of beauty. (The only way to know whether orthodontics has helped or hurt is to have a standard of perfection against which to compare your work.) Most orthodontic indices, beginning with E. H. Angles' classification in 1908, have used an arbitrary classification standard. In each case, the test constructors selected their own face as the ideal! This unconscious chauvinism has had an ironic result. Since the dentists involved in scale development have been Europeans, when dentists in Hawaii tried to use the scales with Asian or black populations they soon discovered almost all their clients needed their teeth straightened. Finckism strikes again! (See Giddon [1980] or Uesato [1968] for a further discussion of this point.)

Finck attempted to provide a feature by feature analysis of what is good-looking. He began his dissertation with "The Evolution of the Big Toe" and moved slowly upward. The flavor of Finck's appalling Victorian smugness is recaptured in his opening passage:

. . . Concerning savages, there is a prevalent notion that, owing to their free and easy life in the forests, they are healthier on the average than civilized mankind. As a matter of fact, however, they are as inferior to us in Health as in Beauty. Their constant exposure and irregular feeding habits, their neglect and ignorance of every hygienic law, in conjunction with their vicious lives, their arbitrary mutilations of various parts, and their selection of inferior forms, prevent their bodies from assuming the regular and delicate proportions which we regard as essential to beauty. (1887, 76)

Finck then itemized each trait—the feet, limbs, waist, chest, etc.— and explained why the Victorian gentleman surpassed all others in beauty appeal. (In a short 467 pages, he managed to insult every existing ethnic group.) The Hungarians are "of a repulsive ugliness in the eyes of all their neighbors." "The typical Jew is certainly not a thing of beauty. The disadvantages of genuine separation are shown not only in the long, thick crooked nose, the bloated lips, almost suggesting a negro, and the heavy lower eyelid, but in the fact that the Jews have proportionately more insane, deaf mutes, blind, and colour-blind" than other Europeans (p. 89). "The women of France are amongst the ugliest in the world" (p. 390).

What about the Americans? Finck quotes Lady Amberley:

They all looked sick. Circumstances have repeatedly carried me to Europe, where I am always surprised by the red blood that fills and colours the faces of ladies and peasant girls, reminding one of the canvas of Rubens and Murillo; and I am always equally surprised on my return

by crowds of pale, bloodless female faces, that suggest consumption, scrofula, anaemia, and neuralgia, (p. 445)

Such was the tenor of Finck's scientific discussion. The problem with Finck's careful enumeration of ideal traits is that nowhere can we take him seriously.

The dream of anthropologists of discovering what constituted "universal beauty" was finally laid to rest in a landmark survey. Clelland Ford and Frank Beach (1951) studied more than two hundred primitive societies. They were unable to find any universal standards of sexual allure. Different cultures could not even agree completely as to what parts of the body were important. For some peoples, the shape and color of the eyes was what really mattered. For others, it was height and weight. Still others went right to the center of things—what mattered was the size and shape of the sexual organs.

To complicate things still further, even if two societies agreed on what was important, they rarely agreed about what constituted good looks in that area. For example, in some societies (like our own), a slim woman is the ideal. The opposite, however, is true in most other societies—the fatter the better. Table 1.1 lists traits people in various societies have considered hallmarks of beauty.

TABLE 1.1 Societies' Preferences in Appearance

NUMBER OF SOCIETIES THAT ADMIRE THIS TRAIT

|

Slim body build Medium body build Plump body build |

5 5 13 |

|

Narrow pelvis and slim hips Broad pelvis and wide hips |

1 6 |

|

Small ankles Shapley calves |

3 5 |

|

Upright, hemispherical breasts Long and pendulous breasts Large breasts |

2 2 9 |

|

Large clitoris Elongated labia majora |

1 8 |

Note: Although Ford and Beach discuss the impact of "man's" appearance on sexuality, in this case "man" means "woman." Although the authors do not itemize the traits constituing handsomeness, other information makes it clear that in various societies there is equal disagreement as to what handsomeness is.

THE FACE

In many societies, the face—delicate boned or broad and sensual—is all that really counts.

Anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski (1929) observed that, for the Trobriand Islanders: ", . . It is a notable fact that their main erotic interest is focused on the human head and face. In the formulae of beauty magic, in the vocabulary of human attractions, as well as in the arsenal of ornament and decoration, the human face—eyes, mouth, teeth, nose and hair—takes precedence" (pp. 295-296).

Those societies that are experts on the face do not agree as to what kind of face is best. Most peoples consider light skin to be most appealing. But many, like the Pima, prefer dark skin; some, like the Dobuans, consider albinos to be particularly repulsive. For the Wogeo, things are even more complicated: tawny-colored Wogeoians prefer light-skinned mates; the cocoa colored prefer dark-skinned mates.

Figure 1.3. In some African tribes, the women insert pieces of wood as large as plates behind their lips. Ubangi women.

THE BODY

In many societies, good looks equals a good body. But again, even the societies that worship fine bodies do not agree on what constitutes a good body. In most societies, robust women are seen as possessing the most sex appeal. Clelland Ford and Frank Beach observe:

[Holmberg writes of the Siriono:] Besides being young, a desirable sex partner—especially a woman—should also be fat. She should have big hips, good sized but firm breasts, and a deposit of fat on her sexual organs. Fat women are referred to by the men with obvious pride as EreN ekida (fat vulva) and are thought to be much more satisfying sexually than thin women, who are summarily dismissed as being ikdNgi (bony). In fact, so desirable is corpulence as a sexual trait that I have frequently heard men make up songs about the merits of a fat vulva .... (1951, 88-89)

In many primitive societies, people are balanced on the fine edge of survival. A fat wife is a status symbol. She graphically illustrates her husband's ability to provide ... to excess.

SEXUAL TRAITS: GETTING DOWN TO FUNDAMENTALS

It is easy for us to understand how critically important sexual characteristics are. The question "Are you a breast man, a leg, or an ass man?" attests to Americans' focus on sexual traits. American men have long been fascinated by big breasts (Morrison and Holden 1971). In 1968, Francine Gottfried of Brooklyn—a twenty-one-year old whose measurements were 43-25-37—generated a riot among staid, Wall Street businessmen simply by walking to work in the morning. At first, only a few bankers, brokers, and clerks waited on the street corner to watch her walk by. Then the crowds grew. The news media began to report on the phenomenon. The crowds swelled. On September 21, 1968, a cheering crowd of more than 10,000 jammed Broad Street (in front of the New York Stock Exchange) and nearby Wall Street. Newspapermen and cameramen from as far away as Australia waited for pictures. Ticker tape floated down from the buildings. Police stood by with bullhorns. In the pushing and shoving, some in the throng were nearly trampled. There was the distinctive thumping sound as the metal roofs of four automobiles buckled under the weight of excited spectators, who had climbed on top for a better view. Francine Gottfried of Brooklyn did not enjoy the spectacle as much as the bankers. She failed to put in an appearance (New York Times, 21 Sept. 1968).

Americans' obsession with breasts might tempt you to assume the fixation is a cultural universal. It is not. In different cultures, the "ideal"

±\J .....--------

size and shape of a woman's breasts vary. Some peoples prefer small, upright breasts. (The Wogeo think breasts should be firm with the nipples facing outwards. A young girl with pendulous breasts, "like a grandmother," is pitied.) Other peoples like long and pendulous breasts. For some peoples the external genitals, the labia majora and minora and the penis, are important. In many societies, elongated labia majora are considered erotically appealing. Young girls are advised to pull the clitoris and the vulvar lips to enhance their sex appeal. Before puberty, girls on Ponape undergo treatment designed to lengthen the labia minora and to enlarge their clitoris. Impotent old men pull, beat, and suck the labia to lengthen them. The girls put black ants in their vulva so that their stinging will cause the labia and clitoris to swell. In America, most men are not particularly focused on this area. Pornographic magazines featuring "beaver shots" appeal to a minority. (Another society's obsessions always seem strange to us.)

In many societies, men's sexual organs are equally important. In the New Hebrides, men choose to emphasize their sexual appeal (see Figure 1.4). Anthropologist B. T. Sommerville (1984) observed:

The natives wrap the penis around with many yards of calico, and other materials, winding and folding them until a preposterous bundle of eighteen inches, or two feet long, and two inches or more in diameter is formed, which is then supported upward by means of a belt, in the extremity decorated with flowering grasses, etc. The testicles are left naked, (p. 368)

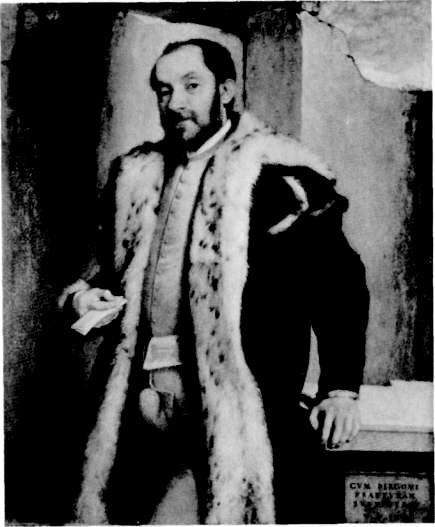

In the 1600s European men often wore codpieces in a similar effort to emphasize their assets. Originally, a codpiece was a metal case to protect men's genitals in battle. Eventually it became a gaudy silk case of colors contrasting with the rest of the costume. Sometimes it was enlarged with stuffing and decorated with ribbons and precious stones (see Figure 1.5).

Lest other society's obsessions with men's genitals seem exotic, note that Rolling Stone once devoted an entire issue to describing how magazines such as Playgirl and Viva test, cajol, and massage the centerfold's penis to just the right stage of arousal (McCormack 1975). Elvis Presley often used a toilet paper tube under tight pants while performing on stage to augment his penis size (Wallace 1981).

As we have seen again and again, however, only a few societies focus on the external genitals, and those that do fail to agree on what constitutes beauty. The New Hebrides model and the Marlboro man are miles apart.

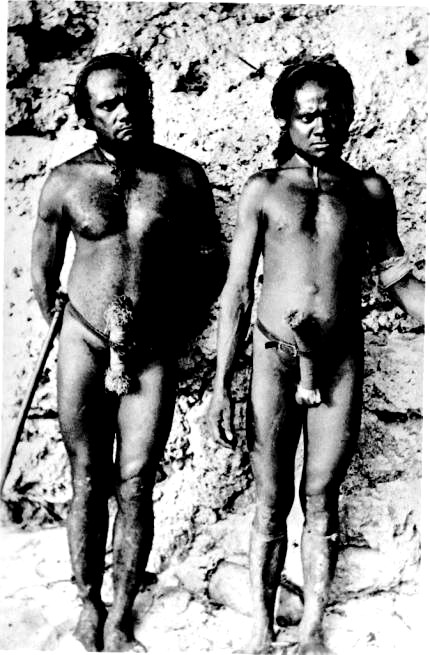

Figure 1.4. In the New Hebrides, men wrap their penes in cloth to form an impressive bundle, held in place with a leather belt. Courtesy Muse'e de 1 Homme, Paris.

Figure 1.5. Portrait of Antonio Navagero by Giovanni Battista Moroni, 1565.

IN SUMMARY

Today, scholars have admitted defeat in their search for a universal beauty. After a painstaking search, after numerous false leads, all their hopes of uncovering such ideals have been shattered. Anthropologists have ended where they began—able to do no more than point to the dazzling array of characteristics that various people in various places, at various times, have idealized.

(Reading this research, one feels a sense of irony. Most of us spend so much time worrying about our bodies, trying to emphasize our "good points" and minimize our "bad" ones. It is disconcerting to realize that with a slight change of time or place all these standards would be turned topsy-turvy.)

Although anthropologists have also been unable to unearth any universal standards for good looks (or for bad looks) within any society, there is, however, considerable agreement on what is appealing and what is not.

The Search for a Local Beauty

In Western society, the media promotes a standard of beauty. Gerald Adams and a colleague (Adams and Crossman 1978) describe television's image of beauty:

Masculinity is judged by overall appearance and impression. The commercials on television will suggest the main attributes a man needs to be considered attractive and desirable. "The dry look" is important. "Reaching for the gusto" is absolutely essential. Using Right Guard and smelling of Brut, English Leather, Old Spice, Musk or one of a half dozen other men's colognes are also necessary. And depending upon the "type", he will drive a certain make and model of car, smoke a certain brand of tobacco, and above all, read "Playboy" magazine. He doesn't have to have a face like Paul Newman or Robert Redford, or a physique like Adonis, though it won't hurt if he does. Primarily, he must be trim, rugged but not too rugged, manly, and have a nice smile. Femininity, on the other hand, is characterized by perfection in every detail. Unlike masculinity, femininity cannot be acquired merely by using the right deodorant and applying a number of external props. A woman must have hair with body and fullness that is marvelously highlighted. Each feature must be an equal contributor to her pretty face. She must have eternally young and blemish-free skin. Her figure must not only be trim, but meet certain "idealized" standards to be considered beautiful. Her hands must be silky soft and not too large. Her nails must be long and perfectly trimmed. Her legs must be shapely, firm, and preferably long. To attain all this, she must "enter the garden of earthly delights" and use "Herbal Essence Shampoo"—hair conditioners scented with lemon, strawberry or apricot, which give marvelous body . . . and rinse or dye, which will make her the "girl with the hair". Her skin must be nurtured with moisturizers and emollients so she can look eternally young. Her figure should surpass that of a Greek goddess by being amply bosomed and slim waisted, but rounded in the hips. As for her legs, "gentlemen prefer Hanes." For finishing touches, she should use "sex appeal toothpaste" and put her "money where her mouth is". She should know that "Blondes have more fun" and Lady Clairol blondes have the most fun of all. For a foundation, she should wear the "cross

your heart bra" and never be without her "18-hour girdle". Finally, above all else, her beauty must look natural, (pp. 21-22; reprinted by permission of Libra Publishing)

Americans and Europeans agree with the media on what is appealing and what is not. In a typical study (this one conducted in Great Britain), Iliffe (1960) asked readers of one of the large newspapers how "pretty" they thought twelve women's faces were. The photos where chosen to represent as many types as possible—they varied in slope of eye, coloring, shape of face, etc. Thousands of readers replied, the critics ranging in age from eight to eighty. They came from markedly different social classes and regions, yet they had similar ideas about what is beautiful. (Additional evidence that, within a society, there is consensus on what is beautiful comes from the work of Cross and Cross [1971] and Kopera, Maier, and Johnson [1971].)

We asked THE GROUP what traits they thought made men and women appealing. Here are some of their answers.

A physically attractive woman is someone with beautiful hair, expressive eyes, high cheekbones, perfect breasts, great ass and legs.

Beautiful people have distinctive features.

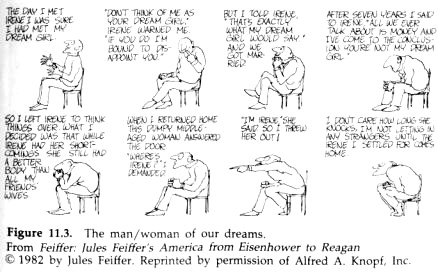

Figure 1.6. Charles Dana Gibson, The Jury Disagrees

A beautiful woman is someone with big eyes, a pretty smile, a thin tapered nose, oval-shaped face, perfect teeth. Usually women have to be perfect to be beautiful. Men don't have to be perfect.

Distortions are ugly. Someone who has a very large nose or big forehead, a lot of freckles, or something like that, is unappealing.

I'm thinking of a man I know who is gorgeous. He has blond hair, light blue eyes, high cheekbones, a long face, and a perfect nose.

I don't like the 5'11" All-American blond with voluptuous curves. It's boring, I like the unusual—a German look ... a beautiful Scandana-vian look.

When I think of beauty, I think of Vogue and high fashion. Since I don't like that, I don't know what beauty is.

No fat chicks here.

I think men whose bodies have gone to seed are a little disgusting.

Beauty is perfection. That perfection can manifest itself in a variety of ways—first and foremost would be in physical aspects.

Though there are differences among these statements, the similarities and agreements are more common.

Several studies have examined how people react to different body configurations. Nancy Hirshberg and her colleagues (Wiggins et al. 1968) conducted the most careful study of what men think is beautiful in women. They prepared 105 nude silhouettes like those in Figure 1.7.

The first silhouette had a Golden Mean sort of body—she had average-sized breasts, buttocks, and legs. (If the Greeks were right, men should have preferred her—they didn't.) The remaining silhouettes' assets were systematically varied. For example, the silhouettes were given unusually large breasts (+2), moderate-sized breasts (+1), standard breasts (0), moderately small breasts (-1), or unusually small (-2) breasts. The silhouettes' legs and buttocks were varied in the same way. Young men were asked to pick the figures they liked best.

The Golden Mean theory turned out to have some validity. Most men thought the women with medium-sized breasts, buttocks, and legs were more attractive than those with unusually small or large features. The men's ideal, however, was a woman with oversized breasts (+1), medium to slightly small buttocks, and medium-sized legs. (Similar results were secured by Beck et al. [1976] and Horvath [1979].)

What about women? What do they find appealing in men? Paul Lavrakas (1975) followed the procedure we have just described in order to find out. He constructed nineteen different types of men's bodies on

Very recently, a

new type of ideal has begun to emerge—a more muscular, healthy, functional

beauty. Time magazine (Corliss 1982) devoted a cover story to this

"New Ideal of Beauty." Time argued that women are reshaping

Americans' notions of beauty. The new woman is natural—graceful, slim, and far

stronger than before. Their bodies are streamlined for motion, for purposeful

strides across the mall, around the backcourt, and into the board room.

Very recently, a

new type of ideal has begun to emerge—a more muscular, healthy, functional

beauty. Time magazine (Corliss 1982) devoted a cover story to this

"New Ideal of Beauty." Time argued that women are reshaping

Americans' notions of beauty. The new woman is natural—graceful, slim, and far

stronger than before. Their bodies are streamlined for motion, for purposeful

strides across the mall, around the backcourt, and into the board room.

Ideals of beauty for women and men may be merging. For men, attractiveness has traditionally been equated with strength, stamina, fitness—all of which allowed men to be more functional. Women are finally joining men in the exercise gym and in corporate chambers (See Figure 1.9).

Summary

Scientists have found no universal beauties. People in different cultures do not even agree on which features are important, much less what is good-looking and what is not.

Within a culture, however, there is considerable agreement about looks. Luckily for the vast majority of us, there is not complete agreement. For example, Cross and Cross (1971), after reporting that Americans and Europeans agree, to some extent, on what kinds of faces are most appealing, report: "The most popular face in the sample was chosen as best of its group by 6 of 207 judges but there was no face that was never chosen, and even the least popular face was picked as best of its group (of six portraits similar in age, sex, and race) by four subjects" (p. 438).

The optimistic hope that someone, somewhere, sometime will think we are irresistible seems a realistic one.

WHAT DO YOU THINK OF YOURSELF?

Now that we have discovered what Americans and Europeans think is good-looking, we can turn to the most personal questions THE GROUP faced:

• How good-looking do you think you are?

• If you could enter one part of yourself in a beauty contest, what would that be?

• Are there certain parts of your body that are especially ugly?

• What do other people think of your looks?

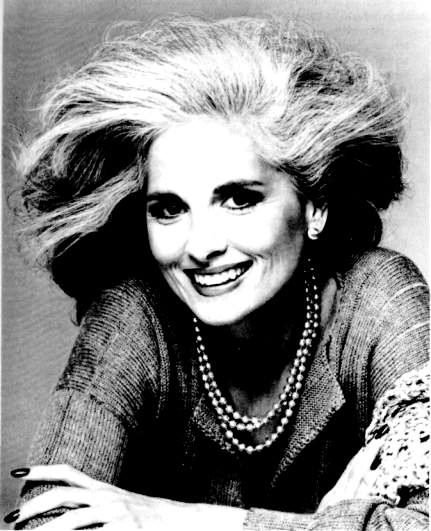

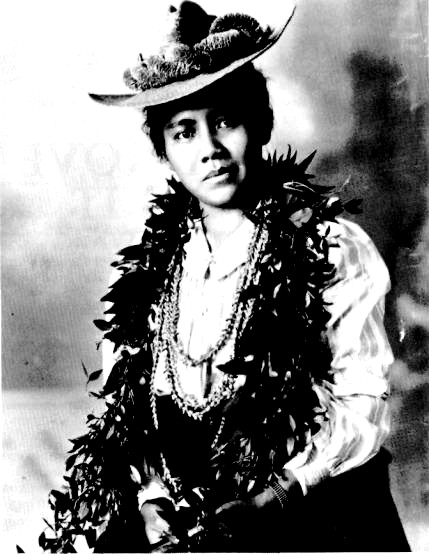

Figure 1.9. Ms. University of Hawaii, Janet C. Vidad, at a beauty and physical fitness contest, 1984.

• Do they ever tell you you're physically appealing? Make cruel comments about your looks? How do you react to such comments?

• How self-conscious are you about your looks?

Scientists have developed a variety of techniques for assessing "Body Image."

We all know about "The Perfect 10". At the University of Wisconsin (Madison) sits The Pub, overlooking State Street. The front wall is solid glass. Men sit on stools, drinking beer, "watching all the girls go by." Each time a woman passes, men shout out "5" or "8" to indicate how good-looking they think she is. Madison women, a bit fiercer than most, occasionally retaliate. One Friday afternoon, a student named Leslie Donovan went down to The Pub with her Alpha Chi Omega sorority sisters, each armed with a stack of flash cards numbered 1-10. When a man shouted his rating, they held up a card indicating his score. (Ms. Donovan once held up a flash card with a "10" on it plus a note attached which said, "My name is Leslie. You can reach me at 222-0101.")

Generally, researchers use a straightforward technique for finding out how people rate themselves. They simply ask them. For example, we (Hatfield [Walster] et al., 1966) asked teenagers: "All in all, how good-looking do you think you are?"

I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I___I

-10 0 +10

Extremely Average Extremely

Unattractive Attractive

In this study, most teens thought they were less than a perfect 6.

Surprisingly, even though this method sounds simplistic, it is an effective way to find out what people think of themselves. This straightforwardness is as good as some of the more elaborate scaling techniques that have been devised. Sometimes, simple is best. Usually, such rough and ready estimates have been enough. On occasion, researchers want to know more about the details of beauty. In such cases, they have proceeded to ask men and women how they felt about almost every feature of themselves—their face, height, weight, and other details.

For example, we asked readers of Psychology Today (a popular magazine) how they felt about their bodies (Berscheid, Hatfield [Walster], and Bohrnstedt 1973). More then sixty-two thousand readers replied. Take a moment to answer our Body Image questionnaire.

Body Image How satisfied are you with the way your body looks?

1. Height:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

2. Weight:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

3. Hair:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

4. Eyes:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

5. Ears:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

6. Nose:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

7. Mouth:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

8. Teeth:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

9. Voice:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

10. Chin:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

11. Complexion:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

12. Overall facial attractiveness:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

13. Shoulders:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

14. Chest (males), Breasts (females):

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

15. Arms:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

16. Hands:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

17. Size of abdomen:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

18. Buttocks (seat):

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

19. Size of sex organs:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

20. Appearance of sex organs:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

21. Hips (upper thighs):

O A Extremely satisfied. O B Quite satisfied. O C Somewhat satisfied. O D Somewhat dissatisfied. O E Quite dissatisfied. O F Extremely dissatisfied.

22. Legs and ankles:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

23. Feet:

O A Extremely satisfied. O B Quite satisfied. O C Somewhat satisfied. O D Somewhat dissatisfied. O E Quite dissatisfied. O F Extremely dissatisfied.

24. General muscle tone or development:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

25. Overall body appearance:

O A Extremely satisfied.

O B Quite satisfied.

O C Somewhat satisfied.

O D Somewhat dissatisfied.

O E Quite dissatisfied.

O F Extremely dissatisfied.

(Berscheid, Hatfield [Walster] and Bohrn-stedt 1972; Reprinted from Psychology Today July, 1972, pp. 58-59.)

Now you know how satisfied you are with your appearance. Do you have more self-confidence than most? ... or less? Let's find out.

Lest We Forget: A Note

You might have felt—as you struggled through the Body Image questionnaire—that we asked too much. Not so for most people. Many people who responded complained we had neglected to ask about the very traits they thought were most important: "I thought your quiz very odd," wrote one New York man. "Nothing about chest hair, pubic hair, or beards." "How one sees oneself in motion—awkward, graceful, rigidly erect, slumping. . . ." "Why didn't you ask about physical deformities?" asked one unhappy man. "My rib cage is deformed as a result of rickets (not to mention a curvature of the spine and a short leg)." "How about blindness?" . . . "bowlegs?" . . . "deafness?" . . . "mastectomies?" One man was annoyed that we did not ask how people felt about their colon, what with constipation and such! Granted we did not ask everything, but we can see how people feel about the things we did ask about.

To find out how people in general felt about themselves, we selected a sample of two thousand questionnaires for closer scrutiny. We selected a sample that came as close to the national statistics as possible. It consisted of 50 percent men and 50 percent women. Forty-five percent were 24 years old or younger, 25 percent were between 25 and 44, and the rest were 45 or older. Table 1.2 shows how satisfied most people are with themselves.

Appearance

American society places so much emphasis on looks. How do most people feel they measure up overall? Only about half the people are extremely or quite satisfied with their looks. Slightly more men than women (55 percent versus 45 percent) are this satisfied. One California man, who was extremely satisfied with his looks, observed: "I have to admit that I consider myself to be a gorgeous person. Your questionnaire made me aware of my body, not just a finely crafted machine, but as a being that is beautiful in an artistic way."

A trivial 4 percent of men and 7 percent of the women are quite or extremely dissatisfied with their overall appearance. The following replies are typical of people in that category:

What we ugly people need is a special book of etiquette that advises us how to behave under the following circumstances: How to respond to remarks like "you sure are ugly." When you see all the easy jobs go to

TABLE 1.2 Satisfaction with Body Parts

|

|

QUITE OR |

|

|

|

|

QUITE OR |

|||

|

|

EXTREMELY |

SOMEWHAT |

SOMEWHAT |

EXTREMELY |

|||||

|

|

DISSATISFIED WOMEN MEN |

DISSATISFIED WOMEN MEN |

SATISFIED |

SATISFIED |

|||||

|

|

|

WOMEN |

MEN |

WOMEN |

MEN |

||||

|

Overall |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Appearance |

7% |

4% |

16% |

11% |

32% |

30% |

45% |

55% |

|

|

face |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

overall facial |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

attractiveness |

3 |

2 |

8 |

6 |

28 |

31 |

61 |

61 |

|

|

hair |

6 |

6 |

13 |

12 |

29 |

22 |

53 |

59 |

|

|

eyes ears |

1 2 |

1 1 |

5 5 |

6 4 |

14 10 |

12 13 |

80 83 |

81 82 |

|

|

nose |

5 |

2 |

18 |

14 |

22 |

20 |

55 |

64 |

|

|

mouth |

2 |

1 |

5 |

5 |

20 |

19 |

73 |

75 |

|

|

teeth |

11 |

10 |

19 |

18 |

20 |

26 |

50 |

46 |

|

|

voice |

3 |

3 |

15 |

12 |

27 |

27 |

55 |

58 |

|

|

chin |

4 |

3 |

9 |

8 |

20 |

20 |

67 |

69 |

|

|

complexion |

8 |

7 |

20 |

15 |

24 |

20 |

48 |

58 |

|

|

extremities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

shoulders |

2 |

3 |

11 |

8 |

19 |

22 |

68 |

67 |

|

|

arms |

5 |

2 |

11 |

11 |

22 |

25 |

62 |

62 |

|

|

hands |

5 |

1 |

14 |

7 |

21 |

17 |

60 |

75 |

|

|

feet |

6 |

3 |

14 |

8 |

23 |

19 |

57 |

70 |

|

|

mid torso |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

size of |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

abdomen |

19 |

11 |

31 |

25 |

21 |

22 |

29 |

42 |

|

|

buttocks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(seat) |

17 |

6 |

26 |

14 |

20 |

24 |

37 |

56 |

|

|

hips (upper thighs) |

22 |

3 |

27 |

9 |

19 |

24 |

32 |

64 |

|

|

legs and ankles |

8 |

4 |

17 |

7 |

23 |

20 |

52 |

69 |

|

|

height, weight and tone |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

height weight |

3 21 |

3 10 |

10 27 |

10 25 |

15 21 |

20 22 |

72 31 |

67 43 |

|

|

general mus- |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

cle tone or |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

development |

9 |

7 |

21 |

18 |

32 |

30 |

38 |

45 |

|

|

sex organs chest/breast |

9 |

4 |

18 |

14 |

23 |

24 |

50 |

58 |

|

|

size of sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

organs |

1 |

6 |

2 |

9 |

18 |

19 |

79 |

66 |

|

|

appearance of sex organs |

2 |

3 |

5 |

6 |

18 |

19 |

75 |

72 |

|

the pretty girls, when they are no more capable than you [sic]. What are you supposed to do when people stare at you? When little children run when they see you! When, as a child, you have to listen to people say that your parents must have committed some grave sin. When you realize that hardened criminals are better off than you because they can at least go to a big city and get lost in the crowd. When people mistreat you and accuse you of being evil. And finally, how are you equipped to behave, when you cannot see any evidence that God loves you?

At the age of twelve, I realized that I was a homosexual. To relieve my tension, I ate and ate until, at the height of five-seven, I weighed 180 pounds and became known as "Fats." At the age of 14, while taking a shower, I realized that no one, absolutely no one would ever love me— I was a fat slob. The next month I lost 30 pounds. It worked. I am now 23 and am 6 foot and weigh 155. I have a lover for the first time in my life who is more than a one-night stand. I am glad that I had that experience. I somehow appreciate inner beauty more than the plastic, store-bought, television ad beauty that drives so many in this world. (P.S. My lover is beautiful. I refuse to answer if I was attracted to his inner or outer beauty first.)

In general, then, men do have better body images than do women. This finding is especially disturbing in light of the fact that women are those most likely to believe that "physical attractiveness is very important in day-to-day social interaction."

For most women, the longing to be beautiful runs deep.

Throughout my childhood I was praised as the intellectual, quiet, thoughtful, conscientious, humorous child of the family—but I desperately wanted to be pretty. I am nearly thirty years old, a "success" in a field few women enter, a "good" speaker, conversationalist, and clown, in a mild sort of way. I am happily married and feel "valued" by my family, but I'd chuck it all if some Mephistophelian character offered me the option of the kind of long-legged, aquiline, tawny beauty praised in myth and toothpaste ads.

A few women noted they were trying to overcome their obsession with beauty:

At a consciousness-raising session, several friends and I decided to go around in a circle and name our most hated features. Hearing each other, we realized how minutely our "ugly" features were noticed. It was definitely a good thing to do.

One's Face Is One's Fortune

Almost everyone was happy with his or her face; only 11 percent of the women and 8 percent of the men expressed any dissatisfaction.

People were not uniformly delighted with every aspect of their faces, however. Both men and women were unhappiest with their teeth— almost one-third were dissatisfied—one-fourth of the respondents complained about their complexions, and one in five did not like their noses.

Sexual Characteristics: How Do You Stack Up?

Given Americans' preoccupation with sex and sexual performance, we thought it possible that most men would be worried about the size of their penises and most women would complain about the size of their breasts. Sex researchers have often observed that couples are unduly worried about just that (Masters and Johnson 1970; Zilbergeld 1978). In fact, Masters and Johnson (1970) were so apprehensive that if word leaked out as to what constituted the "average" breast or penis size, those who fell short would have great difficulty dealing with the facts. Thus, these advocates of academic freedom refused to publish this information.

Ann Landers (1979) receives many, many letters from women worried that their breasts are too large or too small. In 1979 she ran a letter from a woman in Cincinnati who was painfully self-conscious about her small breasts. (A boyfriend had just taken a look at her breasts and told her to "put some calamine lotion on them and they would be gone by morning." She was humiliated and hurt.)

Her letter stimulated a flurry of letters from women suffering from too much of a good thing. One woman reminded her that both psychological and medical problems came with big breasts. Men were only interested in one ("or should I say two") things. She had to dress carefully, avoiding low necklines, clingy fabrics, and knits. Her brassiere required special padding on the strap, and the straps still cut into her shoulders. Ann suggested surgery for breast reduction.

We received many such letters, but they are the exception. Only 9 percent of women are very dissatisfied with their breasts. One woman in four is dissatisfied.

What about men's concern about their sexual endowments? We discovered that only 15 percent of men are at all dissatisfied with the size of their penises; barely 6 percent are "extremely" or "quite dissatisfied". Evidently, only a few men worry about such things. However, we got letters from men concerned about other aspects of their masculinity:

You ask men how they feel about the size of their sex organs. But this is not the crux of the problem. No doubt millions of men, and I among them, have fretted endlessly over the size of their penises, but after all,

except among nudists, this isn't a very crucial matter in day-to-day interaction. It is a secret that can be fairly well kept. There is one secret that can't be kept—how masculine your secondary sex characteristics are—the amount and distribution of your hair, the broadness of your shoulders, narrowness of hips, etc. When I was an adolescent, I had the misfortune to see a sex manual which showed male and female-pubic hair distribution. Horrors—my own pubic hair was the perfect model of the feminine pattern—and still is!

I am going through severe depression, for the following reason: I am extremely unattractive. By 22, a man should look very different from the opposite sex. I don't. My beard growth is nil. The texture of my skin on my face is, if anything, softer and smoother, more "feminine" than most women's. Indeed, on first glance, I am often mistaken for a girl by store clerks and others. This has had a devastating effect on my life. I am a musician, and until I was about 18, when I still looked like a kid, I was able to play with musicians older and more experienced than I, because of my talent. It was assumed that I would "grow out of it." Now, I cannot manage to get into a band, even when the musicians are inferior to me. Needless to say, my social life is just as depressing. In fact, I have none to talk about. My dermatologist sent me to an endocrinologist, as he suspected there might be a hormonal imbalance, but the tests were all negative. I am truly desperate!

There is, however, one group of men exceptionally concerned with their looks and with penis size: gay men. Ten percent of the men and 5 percent of the women who answered our Psychology Today questionnaires had some experience with homosexual activity. Those men who had never experimented with homosexual activity were likely to have a higher body image score than were gay men (33 percent versus 25 percent). Fully 45 percent of the gay men had below average images of their penises on a two-item measure ("satisfaction with size" and "appearance of genitals"), compared to only 25 percent of the other men.

Apparently, gay men, because of men's emphasis on looks in sexual encounters (see Hagen 1979; Symons 1979), become unusually concerned about their bodies. Unlike other men, gay men may have discovered how important beauty is in attracting men; thus, they become as concerned as women have always been about "measuring up." Consistent with that argument is the finding that only gay men are so concerned with appearances. Lesbians are as likely to have a positive body image as other women.

Are women concerned about their genitals? Only 3 percent of the women were dissatisfied with the size of their sex organs. Only 7 percent were dissatisfied with the appearance of their sex organs. A few women worried about having a vagina too small or too large for

their mate's penis. One woman complained that, while having a pelvic examination, her gynecologist observed: "Your husband must complain about sex with you. You are very large, you know."

Weight

To say that most people are generally satisfied with their bodies overall is not to say they are happy with every aspect of their looks. Society places an enormous emphasis on a trim figure. One man volunteered: "As for me, FAT people make me sick. I've never had a fat friend or bedded a fat woman." Almost half of the women and about one-third of the men said they were unhappy with their weight. Twice as many women as men were very dissatisfied (21 percent versus 10 percent).

Perhaps because excess weight tends to settle in the mid-torso area—abdomen, buttocks, hips, and thighs—people worried about their weight were also unhappy about these particular body parts. Some 36 percent of the men fret over that spare tire problem. Women worry about the size of their hips—49 percent were dissatisfied. (We will discuss this issue in greater detail in chapter 6.)

Women are sensitive to the issue of weight. Wardell Pomeroy, who collaborated with Alfred Kinsey in their early interviews (Kinsey et al. 1948, 1953) on sex, discovered that the most embarrassing question he could ask women was: "How much do you weigh?" (This question was more embarrassing than "How often do you masturbate?" "Have you ever had an extramarital affair?" "A homosexual affair?")

When women try to ignore their weight problem, the "bare" facts can suddenly strike them, as Ellen Goodman (1980) describes:

In my life as a clothing consumer I have been subjected to a series of sudden visions known as Dressing Room Revelations. . . . Most of them were unpleasant . . . brought to me by that demon of technology, the three-way mirror. ... It was in a dressing room, for example, that I discovered what I look like from the back. This is something I really didn't have to know. I could have led a decent, understanding life blissfully ignorant of this information, (p. 11)

Height

There is a great deal of evidence that, in our society, height—especially for men—is extremely important. (We will discuss this issue, too, in chapter 7). We had expected to find widespread dissatisfaction with height—we thought men would want to be taller and women would be afraid of being too tall. Not so. Only 13 percent of both sexes expressed any discontent with their height, and actual height was not related to body satisfaction.

ARE YOU AS GOOD-LOOKING AS YOU THINK YOU ARE?

When you filled out the Body Image questionnaire, you had a chance to say how good-looking you think you are. Would most people agree with you? To find out how objective men and women are about themselves, researchers' first step was to develop an "objective" measure of looks. This test turned out to be surprisingly difficult. After several false starts, scientists finally settled on a well-worn method—the method of consensus (see Berscheid and Hatfield [Walster] 1974). Researchers simply ask a number of judges to rate men and women's looks. Judges have their own biases, of course. One judge may like tall, Nordic types, another, short, athletic types, but if you get enough judges, these biases tend to cancel out one another. The method of consensus may be a form of shared ignorance . . . but it is a form of "ignorance" that works (Hatfield [Walster], Aronson, Abrahams, Rottmann 1966).

Scientists have asked, "Do people see themselves as others see them?" The answer appears to be, "through a glass, darkly." There is some correspondence between people's ideas on how good-looking they are and the opinions of more objective judges, but the relationship is far from perfect (see Berscheid et al. 1971; Huston 1972; or Stroebe et al. 1971). Two contradictory processes—the Modesty effect and the Henry Finck syndrome—combine to reduce our ability to see ourselves as others see us.

The Modesty Effect

Cavior (1970) asked fifth-grade girls and boys how they rated compared to other boys and girls in their classes. He found that 75 percent of the girls thought they were the least attractive girl in their class! The girls were not just being modest. They were simply focusing on defects in their appearance that the more objective judges thought were trivial. The girls had adopted an absolute standard of attractiveness—they compared themselves to a "perfect 10" and concluded they did not measure up. The judges, less ego involved, had adopted a relative standard. They asked themselves: "How good looking is this girl compared to other fifth grade girls?"

Cavior also found that fifth- and sixth-grade boys' and girls' guesses as to how their classmates would rank them were almost always wrong. These eleven to twelve year olds had little idea how they rated with their friends. They had a slightly better idea about how relative strangers would feel about them.

The Henry Finck Syndrome

Sometimes false modesty is not the problem—sometimes it's just the opposite. Like Henry Finck, we take it for granted that our country, our race, our family look as people ought to look. For example, Malff (reported in Huntley 1940) found that young adults rated their own thinly disguised profiles, hands, faces, etc. more favorably than others rated them, even though they were unaware it was their own features they were rating. These two opposite processes—false modesty and unconscious arrogance—both contribute to people's inabilities to see themselves as others see them.

As we get older, we do get a little wiser. With age people get to be somewhat better at guessing how others see them. Somewhat better . . . but far from perfect. For example, Berscheid et al. (1971) found that adults' self assessments on the Secord and Jourard Body Cathexis Scale (a type of body image scale) had no relationship to outside observers' judgments about their appearance! Other researchers have found only a minimal relationship (see Huston 1972; Murstein 1972; Stroebe et al. 1971).

So, if you want to know what other people like or dislike about you, you better ask them.

A Note: If you arrange things properly, you can guarantee you will rate a "perfect 10".

1. Ask people with high esteem what they think of your looks. Scientists have found that people who rate themselves highly are equally generous in rating others (Morse, Reis, Gruzen, and Wolff 1974).

2. Avoid beautiful people. They have been found, to be harsher in their judgments. They consider themselves to be the Golden Mean and, in contrast, you lose (Hatfield [Walster] et al. 1966; Tennis and Dabbs 1975).

3. Avoid critics who spend a lot of time thumbing through movie magazines, watching "Charlie's Angels" on television, etc. When they compare the stars to you, you lose out in luster. The contrast effect again (Kenrick and Gutierres 1980; Melamed and Moss 1975). This observation may be reason enough to cancel your date's Playboy or Play girl subscription.

4. Ask men or women who are sexually aroused what they think of you. While aroused, men and women have been found to be unusually appreciative of the opposite sex's looks . . . and unusually harsh in their judgments of the same sex, who are potential rivals. This fact may be reason enough to present your date with a subscription to Playboy or Playgirl.

5. Ask someone of the opposite sex who has been drinking in a singles bar, just before closing time. Scientists have found that people

do get better-looking just before closing time, probably because men and women are eager for company and can afford to be generous (Pennebaker et al. 1979).

6. Ask someone who owes you money.

7. Ask people who look like you. If they have the same color hair, the same body frame, and a mole in the same place, they are going to think you are gorgeous (D. Byrne 1971).

8. Ask people who know you. They are going to be more lenient in judging you (Cavior 1970; Cavior, Miller and Cohen 1975).

9. Be sure to ask your mother! It's her obligation to think you are good-looking.

WHAT IS BEAUTIFUL IS GOOD: THE MYTH