Richard Wagner, O.M.I., M.Div.

![]() GAY CATHOLIC PRIESTS:

GAY CATHOLIC PRIESTS:

A STUDY OF COGNITIVE AND AFFECTIVE DISSONANCE

Dissertation

presented to The Institute for Advanced Study of Human Sexuality

San Francisco, California

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Ph.D. supervised by

Wardell B. Pomeroy,

Ph.D.; Erwin J. Haeberle, Ph. D.; Loretta Haroian, Ph.D.

February

16, 1981

Reproduced here by permission of the author

Dedicated to: Steven E. Webb

Statistical Breakdown of Replies

Chapter 1

Review of Catholic Doctrine

On January 15, 1976 the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of Faith issued a document entitled: Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning. Sexual Ethics. This document, the most recent Vatican pronouncement concerning sexual morality, carried this paragraph as a preface to its discussion of homosexual behavior:

At the present there are those who, basing themselves on observations in the psychological order, have begun to judge indulgently, and even excuse completely, homosexual relations between certain people. This they do in opposition to the constant teaching of the Magisterium and to the moral sense of the Christian people.1

More will be said about this document later. For now, however, this paragraph serves as an appropriate departure for this study of gay Roman Catholic priests. The entire presentation will attempt to isolate areas of conflict in both thought and feeling that surface in the lives of gay priests. This will be accomplished by focusing on the personal struggles of the individual priests who comprise this sample. There are two issues of equal importance to these priests. This study will highlight the conflicts these men may be experiencing, not only because they are gay, but also because they have made a public commitment to celibacy by virtue of their ordination.

To date nothing has been published concerning the sexual attitudes or behaviors of Catholic priests serving in public ministry. The veil of secrecy surrounding this vocation as well as the popular presumption that all priests are sexually abstinent has provided a camouflage for the sexually active priest. But as this study will illustrate, this situation is not without its negative consequences. The sexually active priest is faced with a paradox. The same circumstances that guarantee secrecy also perpetuate the need for secrecy.

By way of introduction, we begin with a brief historical survey of the development of thought within the Roman tradition concerning homosexuality and clerical celibacy. The purpose is to show the confusion surrounding theological speculation on these issues. This survey will begin with the Bible, move through the early Christian Fathers to Thomas Aquinas, and conclude with contemporary opinions.

First, the issue of homosexuality. Six passages in the Bible have traditionally been understood as dealing with homosexual activity. The following biblical quotations are taken from the New American Bible.

Perhaps the single most important passage is the Sodom and Gomorrah story in Genesis 19:4-11.

Before they went to bed, all the townsmen of Sodom, both young and old - all the people to the last man - closed in on the house. They called to Lot and said to him, 'Where are the men who came to your house tonight? Bring them out to us that we might have intimacies with them.' Lot went out to meet them at the entrance. When he had shut the door behind him, he said, 'I beg you, my brothers, not to do this wicked thing. I have two daughters who have never had intercourse with men. Let me bring them out to you, and you may do with them as you please. But don't do anything to these men, for you know they have come under the shelter of my roof.' They replied, 'Stand back! This fellow,' they sneered, 'comes here as an immigrant, and now he dares to give orders! We'll treat you worse than them!' With that, they pressed hard against Lot, moving in closer to break down the door. But his guests put out their hands, pulled Lot inside with them, and closed the door; at the same time they struck the men at the entrance of the house, one and all, with such a blinding light that they were utterly unable to reach the doorway.

Another reference which is said to reflect a general condemnation of homosexual behavior is found in the Old Testament Holiness Code, Leviticus 18:22; 20:13.

You shall not lie with a male as with a woman; such a thing is an abomination.

If a man lies with a male as with a woman, both of them shall be put to death for their abominable deed; they have forfeited their lives.

In the New Testament, two Greek words - malaikoi and arsenokoitai — are usually translated as direct references to homosexual activity. These terms appear in 1 Corinthians 6:9 and 1 Timothy 1:10.

Can you not realize that the unholy will not fall heir to the Kingdom of God? Do not deceive yourselves: no fornicators, idolaters, or adulterers, no sodomites...

...fornicators, sexual perverts, kidnapers, liars, perjurers, and those who in other ways flout the sound teaching... .

Finally, what appears to be the strongest condemnation of homosexual activity is Romans 1:26-27.

God therefore delivered them up to disgraceful passions. Their women exchanged natural intercourse for unnatural, and the men gave up natural intercourse with women and burned with lust for one another. Men did shameful things with men, and thus received in their own persons the penalty for their perversity.

In the Patristic Period there was unanimity on the sinfulness of homosexuality among the leading Church Fathers. Their attacks were based on the general supposition that homosexual acts are unnatural because they are non-procreative in nature. John Chrysostom is particularly emphatic in denouncing homosexual practices as unnatural.

A certain new illicit love has entered our lives, an ugly and incurable disease has appeared, the most severe of all the plagues has been hurled down, a new and insufferable crime has been devised, not only are the laws established (by man) overthrown but even those of nature herself.2

Augustine contends that homosexual practices are transgressions of the command to love God and one's neighbor.

...those shameful acts against nature, such as were committed in Sodom, ought everywhere and always to be detested and punished.3

By the thirteenth century, social pressure against homosexuality through ecclesiastical decrees and national custom became codified in cannon law. Much of the credit for moving the Church in this direction belongs to Thomas Aquinas and his Summa Theoloqica. He states that homosexual acts are unnatural because they are against reason as well as the fact that such acts do not appear among animals.

It must be noted that the nature of man may be spoken of either as that which is peculiar to man, and according to this all sins, insofar as they are against reason, are against nature (as is stated by Damascene); or as that which is common to man and other animals, according to which certain particular sins are said to be against nature, as intercourse between males (which is specifically called the vice against nature) is contrary to the union of male and female which is natural to all animals.4

No serious challenge came from within the Church to this position until the latter part of this century. The publication of Fr. Charles Curran's Catholic Moral Theology in Dialogue in 1972 typified the contemporary movement for a cautious reassessment of moral theology regarding homosexuality.

The homosexual is generally not responsible for his condition. ...Therapy as an attempt to make the homosexual into a heterosexual, does not offer great promise for most homosexuals. Celibacy and sublimation are not always possible or even desirable for the homosexual. There are somewhat suitable homosexual unions, which afford their partners some human fulfillment and contentment. Obviously, such unions are better than homosexual promiscuity...the individual homosexual may morally come to the conclusion that a somewhat permanent homosexual union is the best, and sometimes the only, way for him to achieve some humanity. Homosexuality can never become an ideal. Attempts should be made to overcome this condition if possible; however, at times one may reluctantly accept homosexual unions as the only way in which some people can find a satisfying degree of humanity in their lives.5

In 1976 John McNeill S.J. published his work, The Church and the Homosexual, to date the first systematic attack on the scriptural and theological suppositions supporting the condemnation of homosexuality.

It can, however, be argued 1) that what is referred to, especially in the New Testament, under the rubric of homosexuality is not the same reality at all or 2) that the biblical authors do not manifest the same understanding of that reality as we have today. Further it can be seriously questioned whether what is understood today as the true homosexual and his or her activity is ever the object of explicit moral condemnation in Scripture.6

Throughout the Old Testament Sodom is referred to as a symbol of utter destruction occasioned by sins of such magnitude as to merit exemplary punishment. However, nowhere in the Old Testament is that sin identified explicitly with homosexual behavior.7

There is no reason to assume that Aquinas had any more awareness than the Church Fathers of the homosexual condition. Rather, it is almost certain that in his references to homosexual practices he is assuming that these are merely sexual indulgences undertaken from a motive of lust by otherwise heterosexual persons.8

The greater part of both moral and psychological thinking concerning homosexuality tends to be prejudiced at its source, because it begins with a questionable presupposition. That presupposition, frequently explicit, maintains that the heterosexual condition is somehow the very essence of the human and at the very center of the mature human personality.9

If the findings of this study are correct, then the Church's attitude toward homosexuals is another example of structured social injustice, equally based in questionable interpretation of Scripture, prejudice, and blind adherence to merely human traditions, which have been falsely interpreted as the law of nature and of God. In fact, as we have seen, it is the same age-old tradition of male control, domination and oppression of women, which underlies the oppression of the homosexual.10

Despite the attempt at opening a dialogue, the last official word remains the Vatican's Declaration on Certain Questions Concerning Sexual Ethics. What is noteworthy is that this is the first official statement on homosexuality, which admits the possibility of a homosexual orientation, even though it continues to view homosexuality as pathological in nature.

A distinction is drawn, and it seems with some reason, between homosexuals whose tendency comes from a false education, from a lack of normal sexual development, from habit, from bad example, or from other similar causes, and is transitory or at least not incurable; and homosexuals who are definitely such because of some kind of innate instinct or a pathological constitution judged to be incurable.

In regard to this second category of subjects, some people conclude that their tendency is so natural that it justifies in their case homosexual relations within a sincere communion of life and love analogous to marriage, insofar as such homosexuals feel incapable of enduring a solitary life.

In the pastoral field, these homosexuals must certainly be treated with understanding and sustained in hope of overcoming their personal difficulties and their inability to fit into society. Their culpability will be judged with prudence. But no pastoral method can be employed which would give moral justification to these acts on the grounds that they would be consonant with the condition of such people. For according to the objective moral order, homosexual relations are acts, which lack an essential and indispensable finality. In Sacred Scripture they are condemned as a serious depravity and even presented as the sad consequence of rejecting God. This judgment of Scripture does not of course permit us to conclude that all those who suffer from this anomaly are personally responsible for it, but it does attest to the fact that homosexual acts are intrinsically disordered and can in no case be approved of.11

The history of theological speculation and Church reform regarding clerical celibacy is an equally complex issue. Authors are often indiscriminate in their use of spiritual and ascetical notions such as chastity, virginity, and sexual abstinence when defining celibacy, even though the word itself simply denotes a renunciation of marriage. Because of this it is often impossible to determine the precise ecclesiastical expectations for the clerical celibate. Is one to assume that a public commitment to celibacy entails more than commitment to remain single? While this question remains unanswered the popular interpretation holds sway: celibacy means sexual abstinence.

There is a remarkable difference between the Old and New Testaments with regard to the celibate lifestyle. The Old Testament stresses the virtue of premarital virginity while it promotes the values of married life. Marriage is considered honorable and compulsory for all, and to be unmarried and childless is deemed shameful. The New Testament, on the other hand, emphasizes the value of permanent virginity as a means of worshiping God. This is apparent in the example and teaching of Jesus.

Some men are incapable of sexual activity from birth; some have been deliberately made so; and some there are who have freely renounced sex for the sake of God's reign. Let him accept this teaching who can.12

St. Paul praised celibacy and virginity as a more perfect state, since it is the condition for a more fervent consecration to God.

Are you bound to a wife? Then do not seek your freedom. Are you free of a wife? If so do not go in search of one. Should you marry, however, you will not be committing a sin. Neither does a virgin commit sin if she marries. But such people will have trials in this life, and these I should like to spare you.13

The Patristic Period, the first three or four Christian centuries, saw no laws promulgated against clerical marriage.

Clement of Alexandria commenting on the Pauline texts stated that marriage, if used properly, is a way of salvation for all: priests, deacons, and laymen.14

The earliest legislation comes from the fourth century. The Spanish Council of Elvira in 305 decreed that all clergy were to abstain from their wives. The decree did not forbid marriage; it simply required abstinence.

We decree that all bishops, priests, and deacons, and all clerics engaged in the ministry are forbidden entirely to live with their wives and to beget children: Whoever shall do so will be deposed from the clerical dignity.15

Emphasis on celibacy accompanied the rise of monasticism, which replaced martyrdom as the supreme form of witness to Jesus. The first ecumenical and universal council to require celibacy was the First Lateran Council in 1123. It forbade marriage for the clergy and required that marriages already contracted should be broken. The final formulation of the mandate for clerical celibacy came as a result of the Reformation at the Council of Trent in 1563.

While the celibacy controversy continues to be an issue in the Church, very little contemporary thought has been brought to the discussion. One exception is Donald Goergen's O.P. work The Sexual Celibate. The author combines a mixture of contemporary psychology and traditional theology in his discussion of the celibate lifestyle. Goergen maintains that although the clerical celibate forswears his right to marry he is free to develop affectional friendships. Goergen does not suggest that genital sexuality is proper to the celibate, but he does maintain that celibacy does not mean being asexual.

The sexual life of a celibate person is going to manifest itself primarily in the affective bonds of permanent and steadfast human friendships, which are exemplifications of God's way of loving.16

The primary concern of this section has been the history of clerical celibacy. But one must not overlook the church's demand for sexual abstinence for all its members not validly married. Of particular concern here is the implication for the homosexual. In 1973 the committee on pastoral research and practice of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops approved for distribution and published a paper entitled: Principles To Guide Confessors in Questions of Homosexuality. It serves as an accurate indication of official Catholic teaching and pastoral practice regarding homosexuality today.

Since all homosexual acts are assumed to be intrinsically evil by nature apart from any other consideration, confessors are advised to help homosexuals to work out an 'ascetical plan of life.' Each homosexual has the obligation to control his tendency by every means within his power, particularly by psychological and spiritual counsel. It is difficult for the homosexual to remain chaste in his environment, and he may slip into sin for a variety of reasons, including loneliness and compulsive tendencies and the pull of homosexual companions. But generally, he is responsible for his actions.17

The dilemma of the gay priest, the cognitive and affective dissonance present in his life, is due in great measure to the confusion surrounding the issues of homosexuality and celibacy and their moral and theological implications. Dubious interpretations of Scripture, ambiguous terminology, and diffuse prejudices and fears have all contributed to the confusion. Identifying the difficulties gay priests encounter in personally assessing the impact of theological speculation and pastoral directives in regard to homosexuality and celibacy is one of the intents of the study that follows.

Chapter 2

Methodology

Purpose of the Study

The present investigation was undertaken with several purposes in mind. First, there was an effort to identify the various sexual dimensions present in the histories of a sample of fifty Roman Catholic priests who self-identify as gay. This encompassed more than a survey of the nature and frequency of each subject's sexual behavior. It was also an attempt to capture a feeling for each respondent's growth in his appreciation of himself as a sexual being. Second, there was an effort to examine areas of ambivalence or conflict in thought and feeling regarding the gay priest's "double" social and cultural identity. Third, all of this was undertaken as a step toward an appreciation of the unique position of the gay priest.

It must be pointed out from the beginning that any conclusion about the number of gay men in the Roman Catholic priesthood or the degree, if any, they are exhibiting a particular behavior or characteristic, is not the aim of this study. On the contrary, the fortuitous nature of this sample precludes such generalizations.

Also something should be said about the use of the term "gay." The choice of this term over the more pervasively used "homosexual" or "homophile" is more than a personal preference. It is used to indicate a higher degree of homoerotic self-awareness. Though an individual might experience homoerotic feelings, and even give them physical expression, the term "gay" would not be used to describe him unless his homoeroticism was part of his self-identification. In other words, the term "gay" is used to denote a person's conscious effort to integrate his homosexual orientation with the rest of his personality. This conscious effort presupposes a conceptual framework in terms of which the person tries to understand himself and interact with others. It is important to point out that this definition does not necessarily denote a sexually active lifestyle. It is possible for an individual to self-identify as gay without having had a single overt same-sex experience.

Procedure

This study is divided into two large sections corresponding to the two instruments used to facilitate the inquiry. The first section deals with the respondents' sex histories, while the second is concerned with the respondents' attitudes with respect to their double identity as gay priests.

The sex history selected was an adaptation of the one developed by Kinsey. Its design enabled an in-depth assessment of each subject's current behaviors as well as the biographical context out of which he is now acting. The sex history was administered in a face-to-fade interview, which generally took about 90 minutes. The attitude inventory comprised thirty-four questions. These were divided among four areas of concern: a) conflicts of conviction; b) conflicts in lifestyle; c) conflicts of identity; and d) conflicts in sexual behavior, as well as introductory and summary sections. The respondent was given the questionnaire at the end of the sex history interview with the instruction to return it to the interviewer by mail when completed. Both the sex history and the attitude inventory bore identical code numbers to insure proper coordination of the data.

I was aware that the design and length of the attitude inventory would present problems in the analysis of the data gathered. However, the written responses to the questions would be potentially more enlightening to the unique sphere of this study. It would allow for a greater breadth of expression for the respondent than the statistically advantageous multiple-choice questionnaire.

Statistics

The gathering of the sample of fifty gay Catholic priests was the most difficult part of the process. The circumstances which militate against the participation of gay lay people in studies of their sexual attitudes and behaviors were considerably compounded in this study of gay priests. The fear of disclosure, possible reprisals, ambivalent attitudes, and feelings of guilt were some of the concerns that stood in the way. In fact, only one thing made the process possible. The gay priest, like any marginal personality, needs a support system. There is an informal network of gay priests operative in just about every section of the country. It was this network that was utilized in the recruitment of respondents. A considerable amount of energy and time was exerted in having the sample of fifty represent the broadest geographical distribution possible. This began by contacting key priests in different parts of the country. These individuals acted as liaisons with priests in their vicinity. The liaisons were given copies of a brief description of the proposed study and were asked to distribute them to the contacts they had. If anyone showed an interest in participating in the study his name, address, and telephone number were forwarded to the interviewer. A personal contact was then made for the purpose of setting an interview date. In some cases travel plans dictated the amount of time available in a particular locale

The final sample of fifty gay priests reflects 68% of the seventy-three total contacts made. The remaining twenty-three individuals were not able to participate for a number of reasons. Five were not included because of scheduling difficulties. Twelve were not included because they reconsidered the risk involved and decided against granting the initial interview. Four possible subjects, while undergoing the sex history interview, excluded themselves from the study by not returning the attitude inventory questionnaire. And finally, the interviewer had to disqualify two other respondents: one because he had resigned the active ministry, the other because he was a priest imposter.

Definitions

In an effort to aid the reader in understanding some distinctive terminology used throughout this presentation a brief list of terms are here defined. These definitions reflect the use intended by the author within the context of this particular study.

Catholic priest. A man properly ordained as a public minister in the Roman Catholic tradition, serving in the active ministry. The Catholic priesthood can be divided into two major groups: secular priests, and religious priests.

Secular priest. A priest ordained to serve in a particular diocese or archdiocese. His immediate superior being the local bishop, archbishop, or cardinal.

Religious priest. A priest ordained as a member of an established community or congregation such as the Jesuits or Franciscans. His immediate superior being a provincial or abbot. He is also distinctive in as much as he professes public vows of poverty, chastity and obedience and lives in accordance with specific rules of life as outlined by his community or congregation. The term "religious" may also refer to any individual associated by vow with a particular community or congregation but who is not an ordained priest - such as a lay brother, sister, nun, or monk.

Living in community. The living situation of both secular and religious priests who are living with other priests or religious in an established community house or rectory.

Celibacy. The public profession to remain unmarried made by every Catholic priest at the time of his ordination.

Chastity. One of the three vows professed by a religious man or woman upon being accepted into a community or congregation. It reflects a commitment to the virtue of purity.

BDSM. The mutual exchange of power within the context of a sexual situation. This may include forms of bondage, discipline, and/or humiliation.

Fist fucking. The insertion of a hand or fist into the rectum of a partner.

Analinctus. Anal-oral contact, "rimming."

Chapter 3

The Sample

This chapter is designed to provide an overview of basic demographic characteristics, aspects of sexual development, and current sexual behavior of the respondents in this study. For the sake of convenience, complete results of this part of the study are gathered in the tables, which appear at the end of this chapter (pages 42 - 53). When relevant the reader is referred to these tables. Frequent use is made, both in the text and in the tables, of Gebhard and Johnson's The Kinsey Data: Marginal Tabulations of the 1938 - 1963 Interviews Conducted the Institute for Sex Research (Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1979). Use of the statistics contained in that volume permit ready comparison with the present sample of Roman Catholic priests.

Demographics

Though the sample of respondents in this study was of necessity a fortuitous one, a major effort was made to recruit respondents from all over the United States. The majority, twenty-one (42%), reside in California, while seventeen (34%) live in the Northeast - seven in Massachusetts, five in Pennsylvania, three in New York, and two in New Jersey. An additional seven respondents (14%) live in the Midwest - one in Minnesota, one in Michigan, four in Illinois, and one in Iowa. The remaining five respondents (10%) reside in the Northwest - three in Idaho and two in Washington.

All but two of the respondents were Caucasian; one was black and one identified himself as brown.

The respondents ranged in age from 27 to 58 years. The mean age was 36.4 years, the median was 35 years, and the mode was 32 years. Since all of the respondents are by profession Roman Catholic priests all have achieved a high level of education. Thirty-one (62%) surpassed the theological Master's degree mandatory for ordination into the priesthood. Eighteen (36%) had two Master's degrees, while five (10%) had three Master's degrees. Eight respondents (16%) had attained doctoral degrees.

Sexual Development

The sex history interview began with an evaluation of the personal recreational habits of the respondents. A list of eleven activities was presented to the subject. He was then asked to give the frequency with which he engaged in each activity. (See Table 1, pg. 42)

Four of the respondents (8%) reported that they were recovered alcoholics. It was impossible to determine the percentage of others who might currently be experiencing problems with alcohol. The sample as a whole, however, displayed a high level of awareness about the dangers of alcohol addiction both within the gay community and among their vocational peers. An even greater awareness was expressed about the dangers of using other drugs, although the use of marijuana was considered the least dangerous. It is interesting to note that the respondents in California reported a greater familiarity with and personal use of all the drugs listed. Of recreational activities, the most popular outlet reported was reading. This was followed by cooking, even among respondents who have little opportunity to cook.

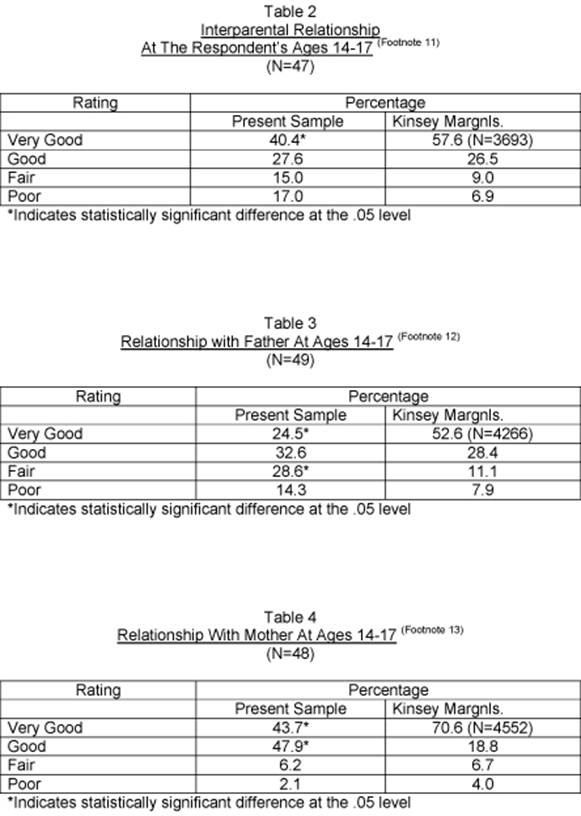

The next part of the sex history concerned family background. The results of these questions appear in Tables 2-4 (pg. 43). Only seven of the respondents (14%) reported having lived on an operating farm for longer than one year. The balance of the respondents were urban, suburban, or small town dwellers all their lives. Thirty respondents (60%) reported that their fathers were still living. Thirty-eight (76%) reported that their mothers were still living. Two respondents reported that their mothers had died prior to the respondents' adolescence; one other reported that his father deserted his family prior to the respondent reaching adolescence. The remaining forty-seven respondents were able to answer questions about the quality of their relationships with their parents, as well as the quality of the relationship their parents shared. Tables 2-4 reflect answers given to these questions concerning relationships, both intra-parental and between the respondents and each of his parents. The rating is based on each respondent's recollection from adolescence.

Generally the respondents recalled that the quality of their parents' relationship during the period of the respondent's adolescence to be average or above average. As for the relationship between parent and son, the affectional ties were reported to be healthier and stronger between mother and son than between father and son. Of the forty-seven respondents able to make the comparison, 51.1% rated the maternal relationship higher, while only 4.2% rated the paternal relationship higher. 44.7% gave an equal rating for both parents.

Five respondents (10%) were an only child. The forty-five respondents who indicated having siblings reported a range of between 1 and 13 other children in their families. The mean number of siblings was 2.9. Eight respondents (16%) were aware that they were not the only gay sibling in their immediate family. Five had a gay brother, three had a lesbian sister.

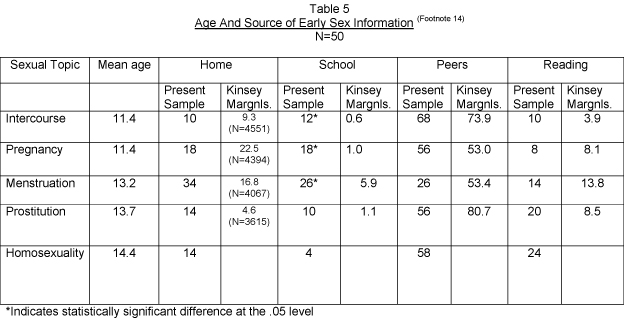

After ascertaining aspects of family background, questions were asked about the nature of each of the respondent's early sex education. The procedure was to record the age at which each respondent had his first fairly accurate notion of suggested sexual topics. Following this the respondent was asked what the source of information was for each of the topics. (See Table 5 pg. 44).

Predominantly, same-sex peer groups were responsible for the greatest amount of early sex information for this sample. The only significant exception was the source of information about menstruation, which was more often the home. When the respondents were asked the extent of more formal sex education in school, only sixteen (32%) remembered receiving formal education of any kind. Of these, the types of education most often mentioned were "family life" courses in high school or "morality" courses in graduate level college. Only seventeen of the respondents (34%) considered one or both of his parents to be influential in their sex education. Mothers were slightly favored over fathers.

Next the respondents were asked to estimate their approximate age at the onset of a number of variables signaling the advent of puberty. Each was asked to recall his age when pubic hair began to grow, when his voice began to change, when his first ejaculation occurred, and when his rapid growth spurt ended. Using this information, a further calculation was made to establish the approximate onset of puberty for each respondent. The mean age of the onset of puberty for this sample was 13.9 years; the median age was 13 years. These figures compare with the mean age of 13.7 years established by Kinsey). In addition to these questions, each respondent was asked to recall his feelings about going through all the pubertal changes. The majority, thirty (60%) recalled negative feelings. These feelings ranged from a general discomfort on the part of some to a real dread and fear on the part of others. The positive feelings reported by the remaining twenty respondents (40%) were also on a continuum. There were those who recalled feeling "okay," and those who were overjoyed at the prospect of imminent manhood.

Inquiry into the extent of each respondent's preadolescent sex play was also made. Twenty respondents (40%) reported engaging in heterosexual sex play before reaching puberty. The mean age at the onset of this activity was 6.9 years. All of the reported partners of the respondents were the same age to within one year. The techniques employed were limited to showing genitalia or a combination of showing and touching. The frequency ranged from 1 to 15 occurrences, although the majority reported no more than one or two occurrences total. There was a slightly higher occurrence of preadolescent homosexual sex play by this sample. Twenty-seven respondents (54%) reported such behavior. The mean age at onset was 7.8 years, and once again all the reported partners were within one year of age of the respondent; and the techniques employed generally included no more than showing and touching of each other's genitalia. However, four respondents reported mouth-to-genital contact and/or anal intercourse. The frequency ranged from one occurrence total to one occurrence a week for three years. Most respondents, however, reported less than five occurrences total. These figures compare with 54.4% found in the Kinsey sample.2 This population reflected a 9.21 years mean age at onset.3

In addition to preadolescent sex play, respondents were asked about preadolescent sexual contact with adults. Five respondents (10%) reported having had such contact, and all were same-sex in nature. Three of these respondents reported one occurrence each. These consisted of a stranger approaching them in a public place, such as a movie theater or a park. There was mutual touching and showing of genitalia involved and masturbation on the part of the adult. These encounters provoked similar reactions in all three respondents. There was a mixture of fear and excitement.

The other two respondents reporting preadolescent sexual contact with an adult had their contact with an older brother. The frequency of contact for both of these was at least twice a month for over a year. One of the two reported being coerced into the activity and finding it dissatisfying. The other respondent, however, reported very positive feelings because the sexual interest expressed was mutual.

Sexual Behavior

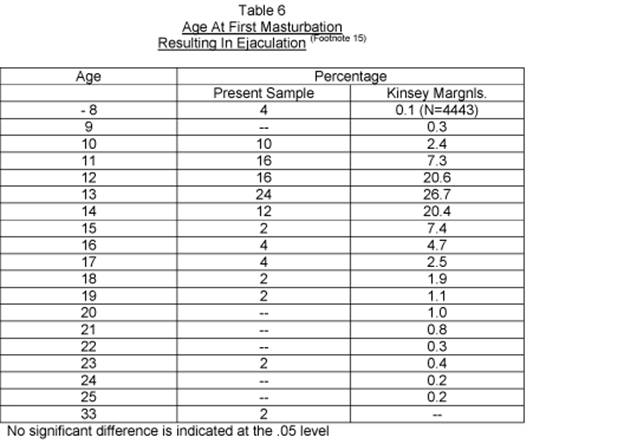

The respondents were asked about the age of onset and current frequency of masturbation. Table 6 (p. 45) charts the onset of masturbation. The mean age of first masturbation for this sample was 13.1 years. The first incident of masturbation occurred through self-discovery on the part of thirty-three (66%) of the respondents. Seventeen (34%) learned of masturbation through the instruction of another. Only seven respondents recalled fearing physical harm as a result of masturbation, and all seven resolved their fears within two years of onset. When questioned about guilt associated with masturbation, only seven recalled being free of guilt from the beginning. Of the forty-three others who initially experienced guilt over masturbation all but six have currently resolved their guilt. It is interesting to note that the thirty-seven who initially experienced guilt and then resolved it were unable to do so until the average age of 23.7 years.

Current frequency of masturbation varies greatly among this sample. One respondent reported his current rate at three times a day, while two others reported their rate at no more than once a month. Only one respondent reported that he was currently abstaining. Of the respondents currently engaging in masturbation, the mean frequency is 3.45 times a week, the median frequency is three times a week, and the mode once a week. By way of comparison, Kinsey found a mean frequency of 1.42 times a week, and a median frequency of .73 times a week for college educated males between the ages of 26 and 30.4

A minority of the total sample, fourteen (28%), had engaged in heterosexual intercourse. Of these, none has had heterosexual intercourse within the past year. The mean age of first coitus for this group was 26.7 years. Six of these respondents reported having just one other-sex partner, while the most other-sex partners reported was four. When these fourteen respondents were questioned about their attitudes concerning coitus, all but one expressed neutral to negative attitudes. The one respondent who expressed a positive attitude believed that he might initiate further heterosexual contacts in the future. Most of those who expressed neutral to negative attitudes saw their coital experiences as motivated by a desire to prove their masculinity or to overcome fears about being gay. Others reported that the reason for their not continuing to seek heterosexual partners was that such outlet was less satisfying than their same-sex outlets.

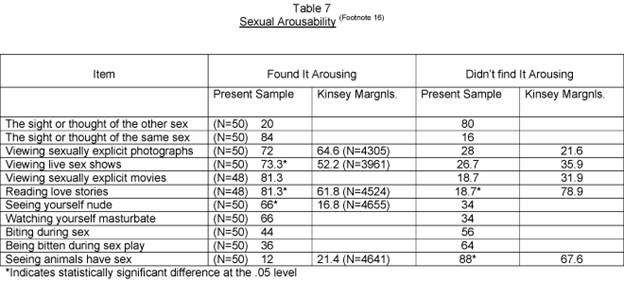

During the interview attention also was given to determining the source and extent of sexual arousability for each respondent. Table 7 (p 46) represents the responses made by this sample to a selection of erotic stimuli. Not surprisingly, this sample's psychosexual response was predominantly homoerotic. And it is interesting to note that even when a given stimulus involved no distinction between other or same-sex, the respondents made clear their preference. That is, the vast majority of respondents who reported being aroused by sexually explicit photos and movies, live sex shows and reading love stories, volunteered that such stimuli were arousing only if they were homoerotic in nature.

The interviewer also inquired about the presence and extent of the respondent's participation in more exotic sexual outlets, such as sex accompanied by physical force, exhibitionism, voyeurism, bestiality, and fetishes. The only areas that received positive responses beyond curiosity were sex with animals and fetishes. Eleven respondents (22%) reported having had at least one post-pubertal sexual contact with an animal. None, however, reported more than three such contacts. Kinsey found that 22.4% of his sample had had sexual contact with animals.5 The source of contact for this sample was exclusively domestic animals, primarily dogs. And the type of contact most often reported was allowing the animal to lick the respondent's genitalia.

Twelve of the respondents (24%) reported having a fetish. Of these, seven had clothing fetishes. Items most often mentioned were jockstraps, swimwear, and leather articles. Four others reported fetishes for parts of the body, specifically hands and feet. Finally one reported a fetish for bondage and discipline.

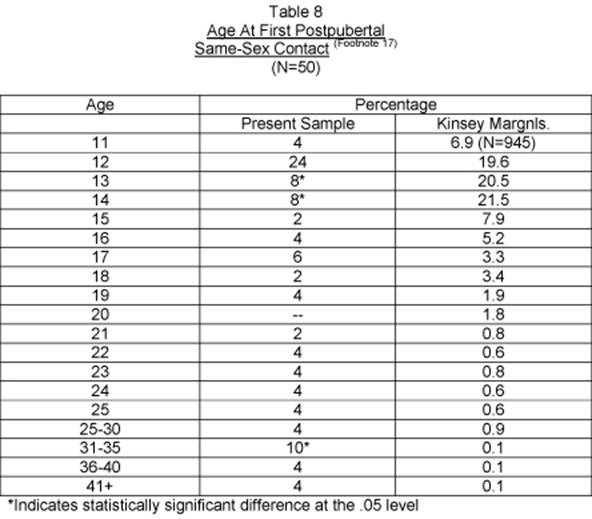

The next phase of the interview dealt directly with the respondents' homosexual activity from first post-pubertal same-sex contact to current same-sex behavior. Questioning began by focusing on the onset, nature, and frequency of the respondents' same-sex contacts. Table 8 (p. 47) gives the ages at which the respondents had their first post-pubertal experience. The mean age of first contact for this group was 19.9 years, the median age 16 years, and the mode 12 years. Eight respondents (16%) reported that their first same-sex contact was with a stranger: a bar pickup, hustler, or the like. This compares with 12% in the Kinsey sample.6 The remaining forty-two (84%) reported that their first same-sex contact occurred with a friend.

Concerning sexual techniques involved in this first experience, thirty-three (66%) reported that it involved mutual masturbation, ten (20%) reported oral-genital contact, and six (12%) frictation. This compares with 59.7% mutual masturbation, 6.2% oral-genital, and 5.8% frictation in the Kinsey sample.7 Only one person in this group reported that his first same-sex contact occurred within a sadomasochistic scenario.

Forty-eight of the respondents (96%) recalled enjoying their first same- sex experience. The two who did not indicated as the reason the unsatisfactory nature of their partners. Nevertheless, despite the overwhelming majority reporting enjoyment, this first encounter was also a source of much guilt. Only eleven (22%) indicated experiencing no guilt over their first same-sex experience.

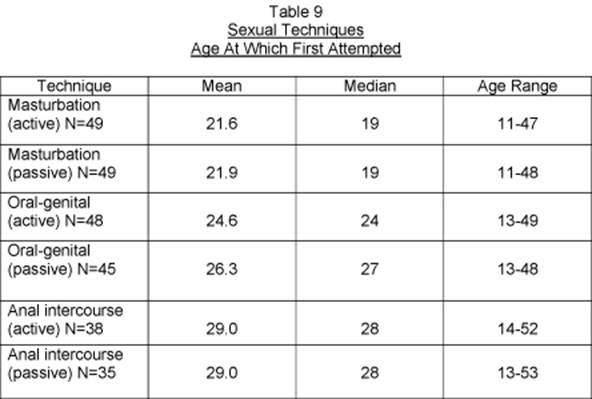

Next the interviewer asked each respondent to recall his age the first time he engaged in a selection of suggested sexual techniques. (See Table 9, p. 48) It is noteworthy that when the technique suggested requires more of a physical involvement, there is a progressive increase in the median age and a gradual decrease in the number of respondents who have engaged in it. Thus, while nearly all the respondents, forty-nine, have been active in the masturbation of a partner, only thirty-five have been passive in anal intercourse, and at a considerably older age. Interestingly enough, when those who had not participated in given techniques were asked why, the majority suggested that some of the techniques (particularly anal intercourse) demanded more of a personal commitment. As one respondent put it: "It is like coming-out. The more you become comfortable with your sexuality the more you are willing to explore new avenues of expression."

After determining the age at which each respondent had his first same-sex contact involving selected techniques, he was asked the frequency with which he engages in those techniques. The results of this question are reflected in Table 10 (p. 49). Kissing was the activity most often engaged in by the respondents. Active oral-genital contact on the part of the respondent was the next most frequent. Sadomasochistic techniques of bondage and discipline were the least frequently used.

This line of questioning continued by asking the respondent about his current favorite technique, the one he would most like to use in every sexual encounter. The results were: oral-genital twenty-four (48%), masturbation five (10%), anal intercourse nine (18%), kissing three (6%), frictation six (12%), bondage one (2%), analinctus one (2%), and "fist fucking" one (2%).

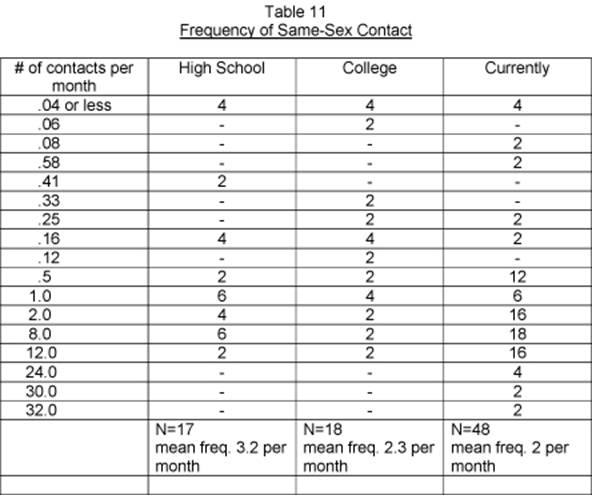

The interview continued with an investigation of the frequency of same-sex contact in high school, in college, and currently. The results are reflected in Table 11 (p. 50). At present, the mean frequency of same-sex contact is two times per week. Only two respondents indicated that they are currently abstaining. After determining the frequency of same-sex contacts, the respondents were asked to give the total number of same-sex contacts made in the course of their lives. In many cases the number had to be approximated, especially when the total number exceeded 100 partners. The fifty respondents averaged 226.8 partners. Of some note is the fact that nine respondents (18%) in this sample had no more than ten partners total, while eleven (22%) reported 500 or more. Kinsey found that 39.2% of his sample had no more than ten partners, while 8.4% reported having had more than 500.8

Thirty respondents (60%) reported that .the majority of their partners were approximately the same age as themselves. Only three respondents (6%) reported that the majority of their partners were distinctly older than themselves, but seventeen (34%) said that the majority of their partners were distinctly younger than themselves. Following this, the respondents were asked the extent of their partnering with men living with heterosexual spouses. Twenty-five respondents (50%) were aware of having had such partners. These respondents averaged 6.4 such partners. Each respondent was asked the extent of his sexual partnering with homosexual "virgins," that is, with individuals for whom that contact would have been their first same-sex experience. Twenty-two respondents (44%) recalled such contact. These respondents averaged 4.6 such partners. It is important to note that the majority of the respondents who express their sexuality in more anonymous situations, such as bathhouses or cruising areas, found it difficult to respond accurately to these questions.

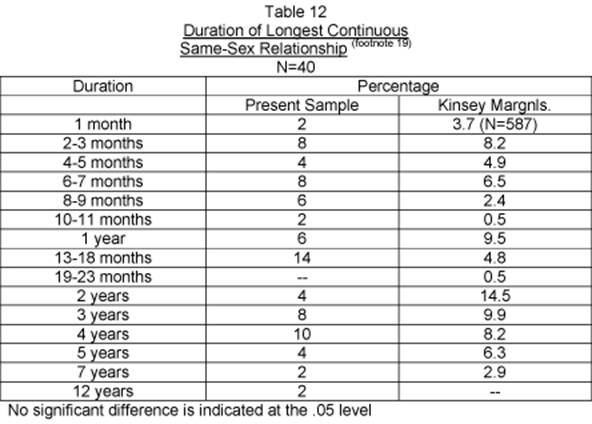

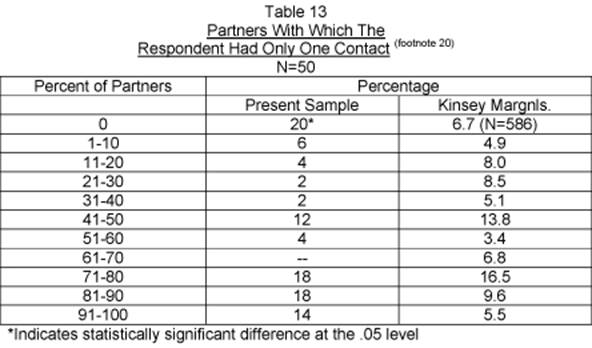

Each respondent was questioned about the duration of his longest continuous sexual relationship (affair). Forty respondents (80%) reported having had at least one relationship lasting longer than one month. The mean duration of the reported relationships was just over two years, 24.3 months. (See Table 12, p. 51). For comparison, Table 13 (p. 51) represents the percentage of total partners with whom the respondent had but one contact. When asked about the number of partners the respondents could recall being in love with, forty-three respondents reported being in love with an average of 5.2 partners. Seven respondents indicated that they had never been in love with any of their partners.

Thirty-one respondents (62%) reported a familiarity with group sex. Of these, seventeen currently engaged in such activity on a regular basis. When inquiry was made into the nature of the group sex contact, most of the respondents indicated that their experiences had been in bathhouses and/or with two other friends. As to the level of enjoyment of group sex experiences, twenty-three (72.2%) reported that they enjoyed their encounters and circumstances. most probably would repeat such behavior under the right The remaining eight (34.6%) found their experiences with group sex dissatisfactory and indicated that they would most probably not pursue such contact in the future.

Each respondent was asked about his contact with male prostitutes. Twelve respondents (24%) indicated having used the services of a hustler. Five of these reported that their total number of contacts did not exceed two or three, while four others reported that this type of outlet comprised the bulk of their same-sex contacts. The most contacts with male prostitutes reported by an individual were twice a month for two years. Respondents were also asked if they engaged in sex in particularly vulnerable places such as bookstores public toilets, parks, and the like. Twenty-three (46%) reported doing so, though only seven of these indicated that they enjoyed this type of outlet and were currently engaging in it. The respondents were asked if they had ever encountered any difficulty or harassment from the police for being gay. Six (12%) said that they had. All reported that harassments were associated with cruising in public places. Two individuals reported having been arrested in a sex-related situation. However, no charges were brought to bear and both were released.

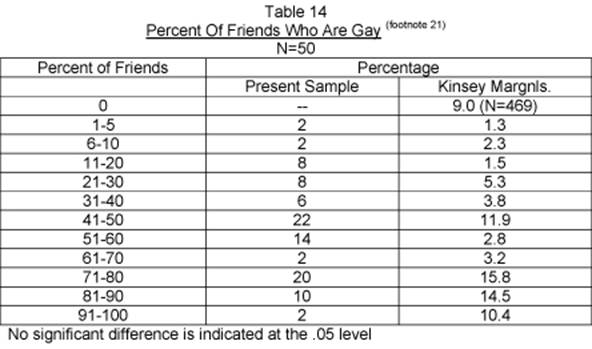

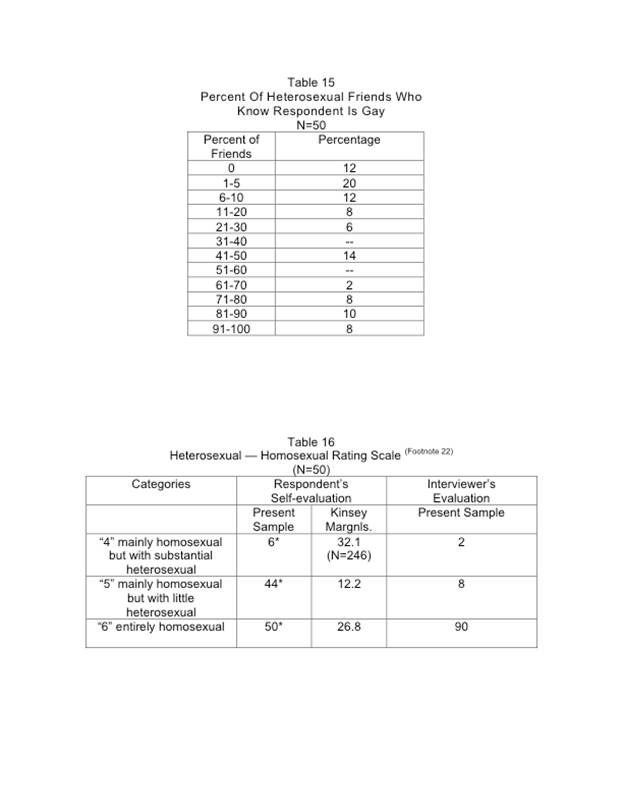

Investigation was made as to the percentage of the respondents' friends who are gay. The mean percentage reported was 53.8%. (See Table 14, p. 52) Each respondent was also asked the percentage of his non-gay friends who knew that he was gay. The mean percentage reported was 36.6%. (See Table 15, p. 53)

The interviewer then familiarized the respondent with the seven-point (0-6) heterosexual-homosexual rating scale developed by Kinsey. Each respondent was then asked to rate himself on that scale, taking into account his behaviors as well as his fantasies. At the same time, the interviewer rated the individual on the basis of information gained through the interview. It is significant that the interviewer disagreed with 40% of the respondents' self-evaluations, and in each case believed that the respondent should have rated himself closer to the homosexual end of the continuum. For example, the individual who exhibits little or no heterosexual contact and who is exclusively homoerotic in his fantasies could not be a Kinsey "4", even though he might consider himself as such. The interviewer would more likely rate this individual as a Kinsey "5" or "6". (See Table 16, p. 53)

The sex history concluded with a few general questions regarding the respondents' attitudes about being gay. Each respondent was asked if he had ever regretted being gay. Sixteen (32%) reported never experiencing any regrets. Nineteen (38%) reported that they had regretted being gay in the past, but no longer do so. The remaining fifteen (30%) are currently experiencing such regret. The reasons given were loneliness and society's disapproval, but the most frequent reason was that their gay lifestyle was in conflict with generally held religious beliefs.

Concerning the respondents' gay identity, a series of questions were asked. Each respondent was first asked if he thought he would continue in a gay lifestyle in the future. Forty-nine respondents (98%) said that they intended to do so. Each respondent was then asked if he would want to change his gay orientation if he were able. Once again forty-nine (98%) showed no desire to change even if they were able. Finally the question was raised as to the ability of the respondent to change his gay orientation if he wanted to. A somewhat smaller majority, forty-five (90%), believed they could not change even if they wanted to. It is interesting to note that Kinsey found a much smaller percentage, 58.2% of his sample, had no desire to change their orientation; 53.3% of his sample believed they could not change even if they wanted to.9

Finally, each respondent was asked what he believed accounted for his being gay. Twenty (40%) had no opinion on the origin of their gayness. Ten (20%) thought that their being gay was biologically caused, that is, that they were born homosexual or that it "just came naturally." Fifteen other respondents (30%) believed that their being gay was psychologically caused, that is, the result of a distant father, or a dominant mother, or an arrested psychosexual development. Seven respondents (14%) felt that the fact most contributive to their being gay was living in an all-male environment. Finally, four others (8%) believed that they had learned their sexual orientation, as well as its expression, as if by chance.

Chapter 4

Results

The Attitude Inventory

Once the sex history interview was completed, the interviewer presented each respondent with a copy of the attitude inventory questionnaire. He was given instructions for its completion and was asked to return it to the interviewer by mail. Both the sex history and the attitude inventory questionnaire bore identical code numbers to insure proper coordination of the data as it was received. When all the questionnaires were gathered each was read for the purpose of statistically analyzing the replies. Later each was read again in order to gather from the whole group some sample responses to be included in this presentation.

It is important to point out at the beginning that since the attitude inventory questionnaire was designed to elicit the respondents' thoughts and feelings on certain issues, and since the format used was highly subjective, the analysis of the replies was made more difficult. Determination of the number of possible categories into which the responses to each question fell was, at times, arbitrary. However, the main consideration in such calculations was to insure a faithful representation of the respondents' attitudes.

The attitude inventory comprised thirty-four questions. Twelve of the questions were divided between introductory and summary sections. The remaining twenty-two questions were divided among the four areas of possible dissonance to be studied. These areas are defined as follows:

a) Conflicts Of Conviction. An investigation of the potential areas of dissonance involved for the respondent as he evaluates his own thoughts and feelings in light of traditional church teachings. The respondents were asked to categorize their thoughts and feelings concerning the church's official positions regarding homosexuality and mandatory celibacy for priests. Each was asked to evaluate his own commitment to celibacy, that is, what he envisioned the celibate lifestyle to mean in his own life. Further questioning focused upon the possible guilt involved for the respondent should his personal views on these topics conflict with traditional church teachings.

b) Conflicts In Lifestyle. An inquiry into the possible dissonance present for the respondent when faced with traditional expectations of the priestly life. The respondents were asked if they are living within the confines of established communities or rectories, and if they have a preference for living alone. Each was questioned regarding the extent his priestly life has fulfilled his needs for intimacy. Further questioning focused upon the freedom afforded the respondent by virtue of his priestly life as it compares to the freedom enjoyed by his gay lay peers.

c) Conflicts Of Identity. An examination of the conceivable dissonance the respondent may experience as he considers his dual identity as a priest and as a gay man. The respondents were asked if they would be concerned if their fellow priests might come to know that they are gay; or if their gay peers might come to know that they are priests. Each was asked to categorize the type of involvement he has with the gay community,' and if he feared blackmail or any other kind of retaliation in light of this involvement.

d) Conflicts In Sexual Behavior. An investigation of the potential dissonance present for the respondent as he ponders his sexual needs and expectations in light of his realized outlets. The respondents were asked if being a priest enhanced or detracted from their sexuality. Inquiry was made into the number of respondents who have lovers, and to what extent those without sought to develop such a relationship. Particular attention was paid to the viability of monogamy in these relationships.

For the sake of convenience, a complete statistical breakdown of the replies to all the questions follows at the end of this chapter.

The attitude inventory questionnaire began with a series of eight preliminary questions designed to gather information about the respondents' backgrounds, both religious and sexual. The first six such questions were demographic in character, deserving only brief attention at this time. The statistical breakdown at the end of the chapter will provide an analysis of the responses to each of these questions.

The fifty respondents reside in four broad geographical areas: the Northeast, Midwest, Northwest, and West. Sixteen respondents (32%) entered seminary during their high school years; twenty-four (48%) during college; and ten (20%) as graduate students. The median age of the respondents at the time of their ordination was 26 years. The ages ranged from 24 to 42 years. The median age at which the respondents began to self-identify as gay was 23.1 years. The ages ranged from 11 to 45 years. The median age, at which the respondents started to "come out," that is, identify themselves as gay to others, was 27.3 years. For most, coming out was a slow and cautious process. Only six (12%) reported that their coming out was simultaneous with self-identification. The longest reported interval between an individual's self-identification and his coming out to others was 26 years. This respondent's gay identity remained a secret from age 13 to age 39. The majority of the respondents had not discussed their gay identity with either their parents or their ecclesiastical superiors. Only fourteen (28%) had come out to their parents. (Four respondents' parents had died before they could share this information). And only eighteen (36%) had come out to their bishops or provincials.

Beginning with question 7 a format of presenting the questions along with analysis and selected replies will be followed.

Question 7:

IF YOU WERE AWARE OF YOUR GAY ORIENTATION IN SEMINARY, DID YOU EVER LEAVE OR CONSIDER LEAVING BECAUSE OF THAT?

Thirty-one respondents (62%) reported being aware of their gay orientation in seminary. The remaining nineteen (38%) had not clearly identified themselves at that time.

Of the respondents who were aware of their gay orientation during seminary, twenty-four seriously considered leaving, or actually did leave for a period, because of their gayness. Some who considered leaving or who did leave for a time believed they were unfit to continue.

I considered leaving out of a sense of 'responsibility' to the church, and fidelity to existing morality. A noble sacrifice.

I often considered leaving because I was gay. I never did because no one I told could believe it, they thought I would outgrow it.

I not only considered leaving, but in fact did leave after three years in seminary. After I worked a few things out I was able to return and feel good about my decision to continue.

Others considered leaving seminary or did leave because they fell in love or were sexually active at the time.

I became infatuated with a seminarian one class above me. I left for two years.

I did not leave the seminary, but did leave the active ministry for two years because of sexual activity.

I chose to leave the active ministry for a while because I fell in love with another priest.

![]() Of the respondents who

were aware of their gay orientation during seminary,

only seven never considered leaving.

Of the respondents who

were aware of their gay orientation during seminary,

only seven never considered leaving.

I was aware of tendencies but dismissed them to environment and the system and stayed.

I never seriously considered leaving because it seemed that celibacy was the only way open to a gay person, whether in the seminary or out.

On the contrary, I felt more honest in my decision-making regarding priesthood.

There were too many like me there to feel I had to leave, so I didn't.

A few of the nineteen respondents who were not aware of their gay orientation during seminary offered that they would have left had they known of their gayness.

They told us that if you were gay it was a sign from God that you should quit. I honestly would have quit if I believed I was gay at the time. This attitude in the seminary was responsible for the incredible repression operative in my life until recently.

Question 8:

DID YOU EVER HAVE ANY SAME-SEX EXPERIENCES IN SEMINARY? HOW DID YOU FEEL ABOUT THEM THEN? NOW?

Twenty-eight respondents (56%) reported having had at least one same-sex contact while in seminary. The remaining twenty-two (44%) reported no same-sex contact.

The majority of the respondents who reported same-sex contact in seminary recalled negative feelings surrounding the events when they occurred, but now view them as growth or learning experiences.

I was guilty at first. Now I see it was an expression of genuine affection. It was a growing experience that I needed.

At first I felt very bad about them. Gradually, I grew to accept these experiences. Now I see them as the experiences through which I learned how to entrust myself to others in love relationships.

I was frightened that it would be found out. I thought it meant I didn't have a vocation. Now I just laugh.

Other respondents recalled experiencing ambivalent feelings as a result of their same-sex experiences in seminary, but now consider those experiences in a positive light.

I had sex a couple of times. Then I felt guilt, but joyous as well that someone could love me that much. Now I feel grateful for them. They put me in touch with my ability to be gentle and affectionate.

I had sex with two classmates. I felt some growing freedom and a great deal of confusion back then. Now I look back on them as 'graced' events. I feel good about them now.

Two respondents recalled negative feelings surrounding their seminary same-sex contacts and continue to see those experiences negatively.

I was afraid that I was going to be dismissed because we were caught in the act. As I look back now I wish it could have been more fulfilling.

There was some embracing in the dark, allowing myself to be kissed and asking a friend to let me get into bed with him. The latter wrecked our friendship. I still have pain thinking about this.

Some of the respondents who reported no same-sex contacts while in seminary offered comments on the subject.

I had no sex while in seminary. I am glad I didn't have to deal with my sexuality until after ordination.

I didn't have sex in seminary -- only during vacation with non-seminarians. When I later learned how much was going on in the seminary, I was somewhat chagrined.

Section 1 — CONFLICTS OF CONVICITON

Question 9:

WHAT IS YOUR ATTITUDE TOWARD THE CHURCH'S OFFICIAL POSITION REGARDING HOMOSEXUALITY?

The responses to this question indicate an almost unanimous disapproval of the church's official position on homosexuality. Forty-six respondents (92%) strongly disagreed with the current position of the church. The remaining four (8%) voiced mixed reactions.

The majority of the respondents rejected the church's position on homosexuality because of its narrowness, especially in the context of its rigid attitude toward sexuality in general.

I find it very narrow and rigid, a view not unlike the church's fixation with respect to all of sexuality. It is, in fact, the church's evident unwillingness to take a fresh look at sexuality that makes me feel more free to do so myself.

We are, in effect, being held hostage for the sake of the church's primary concern for marital (heterosexual) sexuality. Any 'give' in regard to us would crack the criterion for marriage, so...

For the church to accept homosexuality as a given condition of someone's life means a rethinking and revision of attitudes toward all of sexuality.

I believe the church's position must broaden to include the legitimacy and holiness of non-procreative sexuality.

Other respondents based their rejection of the church's position either on the church's lack of compassion or on its lack of knowledge about the subject, while some offered that the church's position is politically and economically rather than morally motivated.

It is sad and a scandal that the church's love and compassion is so rarely extended to sexual minorities in a public manner.

I remember how I rationalized and taught the official position to parishioners and penitents before I came to accept my own sexuality. In the vacuum of no experience, the arguments made sense. Now I see the official teachings to be thoroughly misdirected.

It is completely out of line with the information that we now have through the natural sciences as well as scriptural exegesis. It continues to be extremely oppressive in light of all this.

I think of the church's present attitude toward homosexuality as a political/economic issue rather than a moral one.

Four respondents offered mixed reactions.

It is the beginning in a direction of compassion, but far from hitting the mark in accepting people for who they are.

My attitude is ambiguous. It is unrealistic for the church to accept homosexuals for persons and condemn the emotional and psychological and physical expression of that condition. I also feel that there are positive Christian values about life and sexuality that the church could proclaim to the gay community that is at best neurotic. Unfortunately, the church has no credibility when it speaks about sexuality.

Question 10:

WHAT IS YOUR ATTITUDE TOWARD THE CHURCH'S OFFICIAL POSITION REGARDING MANDATORY CELIBACY FOR PRIESTS?

Forty-five respondents (90%) strongly rejected the church's requirement of mandatory celibacy for priests, while four (8%) disagreed with the requirement in a qualified way. Only one respondent whole-heartedly supported mandatory celibacy.

Those rejecting the requirement of mandatory celibacy for priests did so for a number of reasons, the most common being that a virtue cannot or ought not be mandated.

I believe rather strongly that celibacy is a valid and much needed witness in our culture. It should not, however, be mandatory. Optional may have value; mandatory has none.

Mandatory celibacy is a contradiction in terms. How can a gift or charism be mandated?

This is part of the idiocy that abounds in the church. I see no scriptural or sound theological basis for the practice. I think there should be an option.

Others disagreed with the tradition of celibacy because of its current application to all priests. These respondents believed that celibacy should be required of religious priests by virtue of their special commitment to the church but that secular priests should be allowed an option.

I believe that celibacy is a gift from God and can be embraced freely within religious life. It should not, however, be mandatory for diocesan clergy.

I think that a mandate for celibacy on the part of either heterosexual or homosexual persons in the context of a religious order or congregation is legitimate. Diocesan priesthood should have optional 'celibacy.

Some respondents indicated that the requirement of celibacy was futile because it was not adhered to.

I think the rule should be changed as soon as possible. We don't follow the rule anyway. I bumped into an auxiliary bishop at a gay hotel and saw the ordinary of a diocese at a gay bar across country.

One respondent felt that the celibate lifestyle is in total accord with priestly ministry.

I support mandatory celibacy for the priesthood, more so now that ministry is finally being seen as not merely confined to priesthood. I find no objection to reserving the sacrificial and sacramental aspects of ministry to a clergy totally dedicated by lifestyle to Christ and the church.

Question 11:

HOW DO YOU UNDERSTAND YOUR COMMITMENT TO CELIBACY?

Responses to this question fall into five fairly distinct categories. It is important to note that some respondents equate "celibacy" and "chastity" while others do not.

Eleven respondents (22%) equate celibacy with total sexual abstinence. Some of these indicated that, though this was their understanding of celibacy, they either do not conform to it or oppose it as a binding rule.

Celibacy means no genital contact with anyone of any kind. This is my requirement. Hopefully, it will lead me to become more gentle and loving.

As it is generally understood; in the physical sense. That is, absence of genital activity with others and oneself.

In the traditional sense, meaning no sexual activity. I am beginning to question this understanding. If warm loving sexual relationships help a priest to be a better minister to his community, then why not enter into them, for his own sake as well.

The way that all the laity does -- priests don't screw. This presents an immediate conflict in my life because my lifestyle does not reflect that. However, I would rather live in conflict than play theological 'mind-fuck' games with myself and others.

Eleven other respondents (22%) understood celibacy as a commitment to forego traditional heterosexual marriage or the homosexual equivalent, that is, a permanent exclusive relationship.

I took the promise of celibacy, which means, as the church understands it, not to marry. So I'm keeping that promise.

Celibacy for me means no heterosexual marriage -that's all I ever envisioned it to be.

To me, my promise of celibacy means that I have promised my bishop that I will not get married.

It means that I will not get married to a woman. A ridiculous rule imposed on me, a gay man.

It means the lack of a physical-psychological commitment to another person.

I understand celibacy to mean 'un-marriable' (in the gay context - no covenant with a life-long lover).

I understand celibacy to be for priests a commitment to remain unmarried which for me as a gay man means not to have a lover in the genital, sexual sense.

Thirteen respondents (26%) understood celibacy as a commitment to regulate their sexuality in terms of general Christian moral values, without believing that this precludes sexual expression.

I understand my clerical promise to celibacy as a commitment to put my sexuality in line with the person-oriented and love-oriented directives of the gospel.

Both celibacy and chastity in my understanding have little or nothing to do with my genitals. To see it as a genital issue is to blur the value of these virtues. It is like trying to define a pacifist as one who doesn't carry a gun. Obviously it is more than that. Pacifism, like celibacy and chastity, is a total demeanor, a way one looks at the world.

Chastity means learning how to love people properly. To my mind there are numerous occasions when the proper way to love an individual is non-genital; my mother for example. At the same time there are clearly numerous occasions when genital expression would be proper and appropriate.

I understand my promise to be celibate to be primarily that I am free emotionally and psychologically to be a witness and a minister of God's love in the world. My understanding of these virtues does not preclude genital sex.

Eight respondents (16%) understood celibacy in terms of a commitment to God, gospel values, or a more than usual openness to the needs of others, without explicitly indicating the role, if any, sexuality might have in such a commitment.

I understand it most clearly in terms of availability to many people. I see it also as a mystery of faith: it is a contradiction of so much that is human.

I see it as a sign of the breadth of God's love. Just as I see marriage as a sign of the depth of his love. When I am most genuinely celibate I should then be most open and available to the needs of all with whom I come in contact.

The call to enter life deeply, calling me to participation, involvement and vulnerability.

Saying to the Lord, 'Be my all my everything.'

Finally, seven respondents (14%) expressed confusion on the subject of celibacy, or expressed a feeling of being torn between conflicting interpretations of its meaning. Some offered no definite opinion on the subject.

I have never come to understand it. All I know is that I have been ordained to serve the Lord's people.

With a great deal of confusion! The ideal might be good or was good at a point in history but now it has tremendous political and manipulative overtones. I understand it in the best way I know how — as a process in which I am 'becoming' but in no way means 'fixed'.

In all honesty I am not able to answer right now. I see chastity as an ideal; and I am working toward that. I am sexually active now and I see this as an essential phase in my growth and development. I know with moral certainty that I am so much better off now spiritually and humanly than when I was repressing and suppressing all sexual desire and fantasy.

This one area is causing me personal anguish now. I know that traditionally chastity, as a public profession, has been equated with celibacy. I know in fact that chastity and celibacy are not the same. I guess I just don't have the guts at present to make the distinction.

Question 12:

ARE YOU EXPERIENCING ANY GUILT IN RECONCILING THE CHURCH'S POSITION ON HOMOSEXUALITY AND CELIBACY AND YOUR OWN LIFESTYLE? IF NOT, HOW ARE YOU PUTTING THESE THINGS TOGETHER?

The majority of the respondents, thirty (60%), remarked that they are currently experiencing no guilt in reconciling the church's positions on homosexuality and celibacy and their own lifestyles.

There is no guilt. The church is wrong. The God I believe in is a God who speaks of love, acceptance and especially relationships. The two times I became seriously suicidal over being gay were sinful, the love relationships that I try to develop with others is not sinful. I now leave a relationship feeling more human, more alive, more spiritual.

Now I am not experiencing any guilt. I have put a lot of work into knowing and accepting myself. I take responsibility for my life and I follow my conscience, having given due consideration to the church's teachings.

With the help of two years of therapy and much personal reflection, I am no longer experiencing guilt.

I am not; but I'm also not trying to reconcile the irreconcilable. I try to keep my professional and personal life separate but in tandem.

Only two specified that they are experiencing no guilt, since they are currently sexually abstemious.

At present I am a homosexual in orientation only, not in lifestyle. As long as I remain celibate, there is no guilt, regardless of my opinions on the official church teaching.

A number of individuals reported experiencing no guilt but went on to specify a variety of other qualms and concerns.

Guilt, no! Regret that I cannot be more open and honest, yes. I sincerely regret the necessary dishonesty that makes me appear publicly to be committed to a celibate lifestyle, whereas I am not. But few gays in our society have the luxury of complete honesty. 'Dissent in and for the church' is not simply a matter of theological speculation; it has always been a matter of praxis as well. Like all human beings I need affirmation and support, but approval is not so urgent a need.

No guilt. However, fear of discovery in regards to my sexual activity. Putting it together — I'd say the church has her view and I mine. I consider my view to be healthy and in line with the more intelligent view of scripture and psychology.

I don't feel guilty, but I feel selfish and outside the mainstream. The tension will have to resolve itself soon.

I think that the church is wrong on homosexuality so I don't feel guilty in that regard. I would be more apt to feel it with regard to my choice of celibacy. I feel dissatisfaction, resentment, anger, confusion and fear.

Seven respondents (14%) indicated that they are experiencing a little guilt.

There is little to no guilt since I am more or less celibate in the traditional understanding of the term.

Very little. I am relatively celibate at present. I have done three and a half years of therapy, and have read widely on the issue.

Very little guilt. I see the traditional 'wisdom' as not relating at all to my experience of life and of God. Yet after dealing with some of the unsatisfactory aspects of gay life I feel tempted to return to traditional celibacy. I am also uncomfortable about having a deep commitment to another person as endangering my commitment to God and the church. Yet since my gay lifestyle has helped me very much to be a loving person it has also enriched my priesthood and I have to weigh that factor.

Thirteen respondents (26%) indicated that they are experiencing a good deal of guilt as they try to reconcile the church's position on celibacy and/or homosexuality and their own lifestyles.

The only time that I feel guilty is when I compare my lifestyle with what a 'typical' Catholic would expect a priest to be. I feel no guilt when I compare myself and my lifestyle to my own expectations or those of the gospel.

There is some guilt, yes. Yet I feel psychologically compelled to do what I am doing. I wish I could reconcile it with my public commitment and witness to chastity and celibacy.

Initially there was a lot of guilt, but as I live my life Pm getting tired of feeling guilty. I realize that guilt is my way of holding back and not exploring my sexuality.

I have no guilt in reconciling the church's position and my orientation. I do have guilt in reconciling the church's position and my activity; especially as regards possible scandal.

My only guilt is that my celibacy may be a cop-out.

Question 13:

HOW WOULD YOU CHARACTERIZE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE CHURCH'S ATTITUDE TOWARD SEXUALITY AND THAT OF THE GAY COMMUNITY?

All but four of the respondents made value judgments in their characterizations of the church's and gay community's attitudes toward sexuality. The four who made no value judgments stated what they perceived to be the difference in attitudes but offered no opinion on their relative merits.

The forty-six responses reflecting value judgments fall into four categories of general emphasis. The first category is characterized by a negative appraisal of the church's attitude and a positive appraisal of the gay community's. Eighteen respondents (36%) characterized the difference in this way.

Church leaders stress that the only way sexuality can be valuable and responsible is if it is open to procreation. The gay community sees sexuality in broader terms; that is, the value of sexuality is in the loving.

I see the gay community accepting itself as persons whom God loves and made and who are trying to integrate their sexuality within their whale life. Sexuality is a big plus for gays; for the church it is a minus, limited and negative.

The church still sees sexuality as the source of so much evil; the gay community, despite its many weaknesses, sees sexuality as a liberating force.

The church is not altogether happy about sex. In fact we seem to have more hang-ups about sex than we do about war and racism. In this regard the gay community presents a challenge to the church and society.

The church is 'sure' without being responsibly in-formed. The gay community is an emerging liberated minority, with all the eventually un-fortunate excesses, events and feelings that characterize an enthusiastic, newly liberated group.

The second category indicated a positive appraisal of the church's attitudes and a negative appraisal of the gay community's attitudes. Only one respondent stated the difference this way.

The church seems rightly to emphasize that love and sexuality is much more than genitality. The gay community seems very sophomoric in this regard.

The third category indicated an emphasis on the negative aspects of both the church's and gay community's attitudes toward sexuality. Twenty-six of the respondents (52%) offered such characterizations.

The gay community as I have experienced it admits that it screws around more than the church is willing to admit that her members do. Other than that I am surprised how much alike the two are. There is an amazing amount of guilt, sexual negativity, and 'hang-ups' between the two.